I’m here on the Tibetan plateau, at Baiya Monastery, with my art conservation team completing the job of saving Baiya’s ancient wall paintings. As project manager, my main responsibility is to bring all the people, equipment, food, and materials safely here--four days drive and five high passes from Chengdu. I often joke that once I reach Baiya I can finally kick back and relax. But it’s not quite that easy, because a dozen problems can crop up during a typical day. Here is my log for April 11, 1998.

|

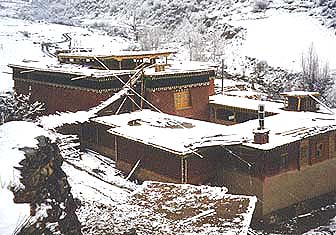

| Baiya Monastery |

I wake up at 7:15 to find my glasses squashed, crushed between the heavy wooden shutters

that block the bitter cold outside. My spare pair is one ocean and half a continent

away. I spend ten minutes straightening them out before beginning ablutions with

ther-mos-water, basin, soap, and comb. My roommates Peng Jing and Karen Yager wake

at the same time. The rest of the team is lodged in twos and threes in chambers all

over the monastery. I cross the courtyard to our common room to choose from a

do-it-yourself menu of tsampa, butter tea, bread, instant noodles, oatmeal, Tibetan

pastries and dried fruit. Alas, our honey and jam went missing on the road somewhere, so

we shall have to do without.

My first task is to meet with Denba Daji, number two “old boss” of this team, to set wages for our six art conservation apprentices. Two came from Chengdu, three are from the Kangding Tibetan school, and the last is a local chap. Their leader, Deshi Yang Jin, is joining us for the third time, and is well on her way to becoming a qualified conservator. The others are newer, and with varying backgrounds, so the question of fair compensation is a bit tricky, but Denba helps me work it out.

Next I go to the temple to find chief engineer Xiong Xiong, monastery manager Tenzeng Nyima, foreign affairs bureau representative Liu Yibing, and my trusty assistant Wu Bangfu deep in discussion. Jonathan Bell, an art scholar the Univeristy of Paris-Sorbonne, is listening in. The problem is, Jonathan wants to photograph the murals. Or-dinarily this is not allowed. None of my staff are entirely sure which government bureaus we should ask, and everyone is reluctant to take responsibility for deciding. The conver-sation moves in circles from the Dege Religious Affairs Bureau to the prefectural Foreign Affairs Bureau, to the Dege Administrative Affairs Bureau, to Public Security, to Tenzeng Nyima himself.

We decide that I should compose a written proposal, which I do, scrupulously and at great length, in English. Liu Yibing and Wu Bangfu then attack the job of translation. I give four reasons why photography is necessary. My canny lieutenents delete the one about documenting the murals for scholarship purposes because, as Mr. Wu explains, “If we want to photograph the murals for research, then we should pay.” We slave like dogs over this document, but in the end decide not to send it to Dege today, but rather to wait until one particularly friendly official returns from a trip out of town. In the end, Tenzeng Nyima orders workers to take down the cloth that covers the murals, anticipating that permission will be granted in the end (it was), and Jonathan can get started.

|

| Asian art history scholar Jonathan Bell documents the content of Baiya's murals. |

Just before lunch an adorable baby girl arrives needing oral rehydration salts, which I fetch out of the expedition medical kit. Logistics assistant Peng Jing, conservator Donatella Zari, apprentice Yang Jin, and I take turns holding the baby while the family stands by, watching silently. Mindful of the scene’s PR potential, I ask cameraman Qimei Dorje to film me with baby in my arms--but on second thought I wonder if this isn’t perhaps a bit too much, as if I was running for public office or something. An old woman comes to ask for medicine for her bad eyes, but we have nothing to give her.

We eat lunch, the whole team of seven foreigners, four Chinese, and eight Tibetans crowded in the lively common room. The cook has made green root mixed with mush-rooms, sauted potatoes, and turnips with fat pork. Almost all of food supplies were brought from a long distance, for there is nothing available here except tsampa, butter, yak meat, and tea.

The conservators need the big room cleared so they can work. I relay this request to Xiong Xiong, who dispatches local laborers to carry out sacks of grain, cement, ritual implements, and other dusty objects. The building is still undergoing reconstruction, and it’s full of the sounds of hammering and sawing. Workers haul stones and clay up the steep staircase. Logistics assistant Peng Jing, conservator Karen Yager, and student Tsering Pelo work for a couple of hours cutting sheets of gauze, which will be applied to the murals. Others arrange a work space on the monastery roof, and begin sanding clay from the back of the first painting.

Xiong Xiong wants to call a couple of carpenters out from Dege. The carpenters we’ve got will leave in a day or two to plow their fields, he tells me. Donatella Zari says after the scaffolding is built we don’t need any more carpenters. I worry that we might need them after all, but nevertheless two sounds like too many. I tell Xiong Xiong not to call them, figuring that if we suddenly need them we will find then locally.

Monastery manager Tenzeng Nyima departs for Dege with a shopping list, letters to deliver, and assorted other errands. Minutes afterward the conservators report that the electric sander is broken and we need to buy another one, preferably two. Student Guo Tao is enlisted to make the run to town, which he will do by hitching a ride on a logging truck. I advance him 800 yuan and he makes out a careful receipt.

Lunch is barely cleared from the table when we are visited by three bureaucrats from Babang Township. In these rustic regions, government leaders are identified by their leather jackets. One of them is the author of the Annals of Dege County, and he’s extremely knowledgable. I give him a long interview, learning various tidbits about history, religion, economy, culture, educational infrastructure of the county and the township. The other two visitors sit listlessly, smoking and sipping butter tea. We fix dates for an excur-sion to Palpung Monastery, located just above the township headquarters. We talk about possible export of medicinal herbs from Dege County, and arrange a letter of invitation for an American friend of mine with strong interest and contacts in this area. We adjourn, and the men file out to their waiting car.