asianart.com | articles

Articles by Gary Gach

Exhibition Photos

Download the PDF version of this article

Contemporary Tibetan Artists at Home & Abroad

Berkeley Art Museum (BAMPFA), U.C. Berkeley

October 3, 2018 through May 26, 2019

by Gary Gach

Published 17 October, 2019

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

BOUNDLESS is an exhibition of work by seven members of a burgeoning, vibrant, cohesive community of contemporary Tibetan / Himalayan modern artists who know and support each other's work. Some live in the East; some in the West. Some are self-taught; others, highly trained.

As I enter, I am reminded of how Edward Said points out that it may be impossible to truly represent anything – yet representation bears within it "common history, tradition, universe of discourse."

Thus, curator Rosaline YiYi Mon Kyo punctuates the contemporary work with traditional Tibetan art and ritual objects drawn from various sources, for contextual reference. In the center of the room and on the walls are a 14th-century Hevajra mandala, a 16th-century bronze of Vajrapani, a copper sculpture of Cakrasamvara and Vajravarahi, an18th-century thangka of a protector deity, a gorgeous ritual conch shell with streamers, and so on.

Untrained as I am in Tibetan art, the enormous power and brilliant innovations of these seven artists nevertheless inspire me to bear witness to their creations. So, as I circumambulate the room, I'll record what I encounter.

Beginning here

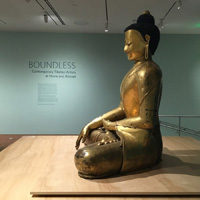

Fig. 1 At the entrance sits a monumental 14th-century Tibetan gilt bronze Buddha. Altho' a sculpture, without living eyes to see us, his representation of Enlightenment is inclusive, taking everyone and everything in this room, and beyond, as witness. With one hand, he touches the earth, calling on all creation as authority for claiming Supreme Enlightenment. Ultimate Awakening. His smile is serene yet triumphant, vanquishing all human frailties.

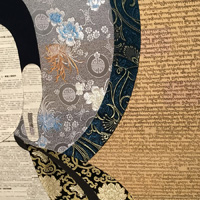

This powerful, anchoring sculpture is book-ended on either side by two pieces from 2014 by Tenzing Rigdol. Formally, these also appear to be portraits of the Buddha. Each is simultaneously classical and modern. In each, the figure is outlined in black.

In The White Proposal, woodblock lines of prayer almost sub-audibly intone across their background. (The artist's paternal family manufactured ink for printing scriptures.) The Tibetan background text is juxtaposed with Chinese – a "white paper" proposal for self-governance, prepared by the Tibetan Government in Exile for consideration by the Chinese government. A collage of this text forms the body and face of the Buddha.

Fig. 2 |  Fig. 3 |

Fig. 4 |

Fig. 5 |

Fig. 6 |

Fig. 7 |

Fig. 8 |

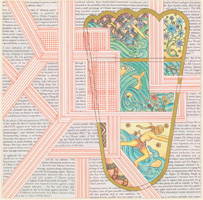

Moving to the north wall of the room, I see another example of one of the exhibit's primary binaries – tradition and innovation. Traditionally, footprints can connote a depth and range of meaning in religious iconography. Angels don't leave footprints. At Passover, Jesus washed his disciples' feet. And, in the Buddha's time, his disciples wanted to make images of him. But he didn't want people to fetishize him, leaving it open for everyone to work out their own enlightenment, as lamps unto themselves.

Fig. 9 Still, the pictorial aspect of the devotional impulse deeply rooted in India eventually prevailed. But at first, rather than portraits, artists sculpted and painted images of the Buddha's footprints. Curator Kyo chose a fine 14th-century painting of footprints of the Third Karmapa. The two footprints are framed by a representation of the Kagyu lineage, via 28 figures human and transcendental. In each sole, a Wheel of Dharma is flanked by the Eight Auspicious Symbols.

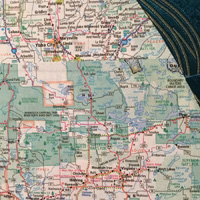

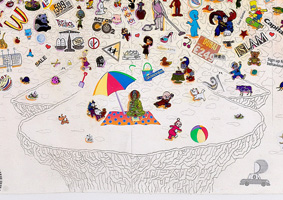

To the right, is another pair of footprints, Exile in the Garden of Eden, painted in 2017 by Tenzing Rigdol. Born in Kathmandu, of Tibetan heritage, he's never seen his homeland. He invites us to consider the human condition in a reworking of the foundational story of the Fall.

The pair of footprints and their background are intersected by various tracks and grids of parallel red lines, a familiar gesture in his repertoire. I don't know yet what he intends it to represent, but to me it feels like the inevitability of rectilinear reality piercing realms of imagination. The background is another collage of cut-ups of text, this time in English: pages from the book Buying the Dragon's Teeth (2005). Composed by Tibetan writer and activist Jamyang Norbu, the text uncovers the structures and economics underlying China's presence in Tibet. The two footprints sketch a disjunctive, surreal, penetrative, provocative narrative.

Fig. 10 |

Fig. 11 |

Fig. 12 |

A chorus of three identical birds open their wings in a symmetrical pattern. (Are they an image from the Garden? Or a detail of a pattern from an illuminated manuscript?) Next to them, a bunch of barrel beads are closely clustered together, loose, lacking a common thread.

Within the heels, a wayfarer is feeling his way forward, head entirely bound in strips of cloth. At one point, he's moving amidst the stars, holding a staff and a flower. Elsewhere, with flowers in the sky, he's alongside or atop waves, arms outstretched, reaching, but his hands are beyond the frame.

All in all, it's unclear if there is a path back to the Garden. And yet we see its traces even today. As I take a step back, my brain ponders, as if on its own: "Ultimately, from our limited human perspective, isn't everything we see before us footprints of the past?" And, like the figure in Tenzing Rigdol's picture, I move on…

The World's Highest Train Ride

The next pair of paintings are drawn from several works painted in 2006 by various Tibetan artists, using as a springboard the opening of the world's highest train. This new railway provided the first direct access between inland China and central Tibet.

One the one hand, it's clearly an engineering marvel of tunnels, bridges, and elevated tracks. Its impact on Tibetans is another story. The cost of building the line ($4.1B) exceeds Beijing's budget for hospitals and schools in Tibet over the last 50 years. Hardly any Tibetans work on the train. Along with Chinese industrial products, thousands of Chinese tourists debark daily.

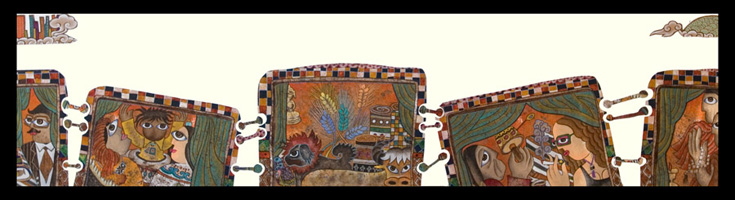

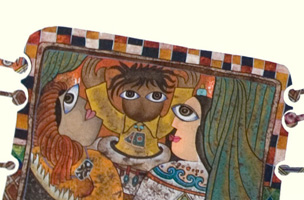

Fig. 13 One painting, Train, is by Dedron, a painter in Lhasa who's taught art at a local school for the blind. Here, the so-called outside world is left blank, (one of her trademark choices), except for skyscrapers in the upper left to mark Qinghai, and nature in the upper right, for Lhasa.

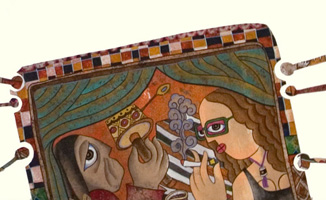

Representing the train car by car, each car feels over-crowded, claustrophobic. Curtains of one car are parted, revealing people with differing complexion and attire, and strange hair-dos, up against each other but none seeing eye-to-eye. In another car, a Caucasian tourist with wavy hair, in a low-cut dress and expensive glasses, holds a cigarette billowing smoke in front of the stoic but grimacing face of a Tibetan nun turning a prayer wheel.

Fig. 14 |

Fig. 15 |

Fig. 16 |

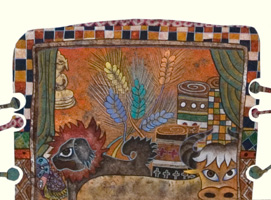

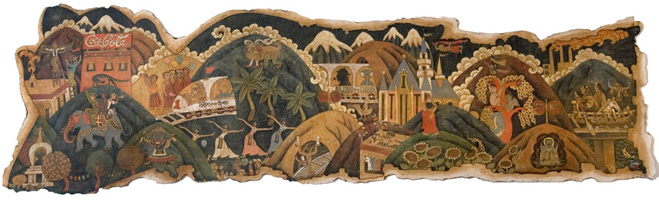

Fig. 17 Lhasa Train is by Gadé, who also still lives in Tibet. Gadé's paints on a stippled ground, on handmade paper, with jagged borders framing the scene. Yet, as with his Garden, and Dedron's train, everything's flattened out, two-dimensional. This tactic is suggestive, the way a Tibetan thangka or mandala is an invitation to view a two-dimensional image as a map of a three-dimensional visualization.

(Parenthetically, I wonder if Tibetan artists enjoyed reading comic books as kids, and now enjoy painting in that way, themselves.)

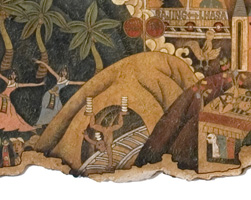

The overall design is quite lively, with round, bowl-shaped hills and high mountain peaks – a stylization of landforms referenced in an adjacent thangka of Milarepa. Where the thangka combines scenes from Milarepa's life with elements of his teaching lineage in a coherent narrative, the disjunctive imagery of Lhasa Train might make even Fellini's jaw drop.

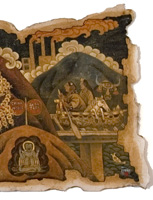

This train is on tracks, but its conductor, wearing earphones, steers it with a wheel. But since a train runs on tracks, it can't make any left or right turns. Behind the train, two Tibetan women in a boat loaded with a horse and a bull, row their way along the tracks, above the water way below.

Fig. 18 |

Fig. 19 |

Fig. 20 |

Fig. 21 |

Fig. 22 But, wait – there's more. Passengers crammed together in one car include a Buddha wearing a grey shirt; Sherlock Holmes; and a bug-eyed alien. The train waves a red flag, as is a man, up ahead, climbing a ladder to the roof of a building where a man in a suit and tie, also on a ladder, with his outstretched arms fitted into a pair of artificial wings, is about to leap. Atop another roof, a buxom woman in sunglasses sunbathes, while a monk in the sky flies by on an undulating red scarf.

In the background, a billboard advertises Coca Cola, in front of snow-capped mountain peaks lined with clouds; further back, factories belch scary-looking fumes. And that's not even the half of it.

New Art Forms

Besides painting and sculpture, present-day Tibetan art also includes installation, performance, and cinema. So, in conjunction with BOUNDLESS, the museum's Pacific Film Archive (PFA) screened three films by Pema Tseden. In the room, three short videos played continuously. Benchang's Floating River Ice documents a performance piece from 2003. On Buddha's birthday (Saka Dawa), the artist drew white chalk to mimic ice at a street intersection in Lhasa, on the route for the devout but also near some lavish Chinese restaurants. As the artist comes in and out of focus, we hear and see passing worshippers, barking dogs, and honking cars.

In Drifting (2010), artist Tsweang Tashi dresses in black silk and floats down a river in a yak-skin boat. With him are women dressed up as funky beer-sellers, countering the romanticized paintings of Tibetan nomads sold to tourists. The video ends by panning out, first to take in the bridge connecting Lhasa to the railway station, then further to take in the towering mountains that diminish the bridge and high-rise buildings.

In Displaced Mountains (2018), Marie-Dolma Chophel pours sand, traditionally used to construct mandalas, to create shifting ridges, slopes, and crags of a miniature mountain. Eventually, the illusion of a mountain is swept away to reveal a painted illusion underlying the sand.

Inner & Outer

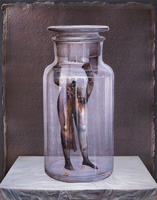

Fig. 23 Nortsé has a single work in BOUNDLESS. No two works of his I've seen as yet are similar. Bottle on White Tablecloth is a reasonably large canvas, combining oil, acrylic, and digital photo. (It's fun to try to tell which is which.)

At first glance, it looks like a Western still-life: a bottle on a white tablecloth. Look closer. Within the bottle, a pair of disembodied, hollow arms hang suspended mid-air. A torso, with decaying legs, is cloaked in Eastern fabric. Is it a miniature deity? Or is the bottle several feet tall?

Further questions. Beside the figure, is the bottle filled with transparent embalming fluid? Or empty? And, no, it's not the bright museum lighting bouncing off the painting's glass making it hard to discern certain details clearly. Rather, the hyper-realist rendering of the bottle's glass surface reflects presumptive light that obscures details. (This goes a step beyond René Magritte painting a dark strip at the upper margin of a painting, as if it were cast from a museum's light against its picture frame.)

Is one hand holding something? Does the other arm even have a hand? Clearer, but still ambiguous, are five pieces of paper, possibly photographs, at the bottom of the vessel, plus a tiny white stone – a pearl? Quite vivid are faint folds on the tabletop; at its edge, a tablecloth shows a jumble of creases, yet relatively flat, rather than rich folds common to still lives. Behind all this, as a backdrop, is what might be a large sheet of baked clay, with particularly jagged edges. Or is it a blank sheet of handmade paper?

Seen through its neck, the bottle seems hermetically sealed. Airtight. Whatever's left of the figure, he couldn't get out without a feat of magic. Unspoken is the implication of a very real dilemma. Nortsé, Dedron, and Gadé can't get visas out of Tibet. Meanwhile, like the apparition in the bottle, they're on exhibit here, in the West. Yet other artists, such as Gonkar, Tsherin, Rigdol, can't get visas in.

Buddha In Our Times

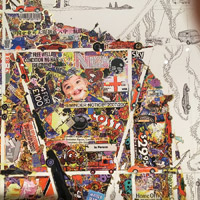

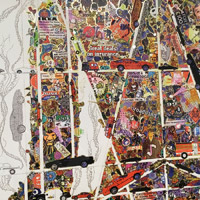

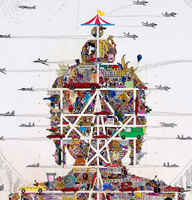

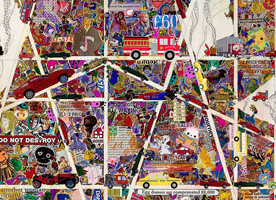

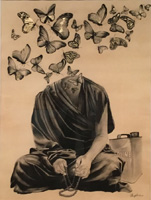

I am now standing directly opposite the monumental earth-touching Buddha. He and I are facing Buddha In Our Times, directly across the room, by Gonkar Gyatso (born in Lhasa, now living in Dharmsala, London, New York, and Chengdu). The contemporary work is immediately recognizable as also a seated Buddha.

Fig. 24 |

Fig. 25 |

Fig. 26 |

Fig. 27 |

Fig. 28 |

Fig. 29 |

Fig. 30 |

Fig. 31 |

The Couple

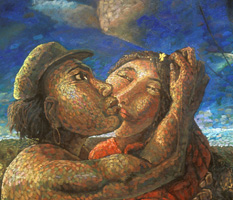

Contemporary Himalayan/Tibetan artists have their own takes on the universal, evergreen theme of lovers. The curator reminds us of the common Buddhist symbol of yab yum. Tsering Nyandak's Lovers (#6), on the other hand, are something else.

Fig. 32 |

Fig. 33 |

Fig. 34 |

Considering the painting further, the lovers' environment is actually as interesting as they are. The vigorous rendering of the landscape in which they've plopped themselves down (a field of grain? weeds?) is echoed in their own rendering. Yet there's an odd contrast between the energy of the lovers and the land – vs. the clouds. They seem like abstract, solid forms, hung suspended, which could crash to earth with a loud thud. One cloud, off to the left, isn't a cloud but an orb, flanked by two cirrus wisps (wings?).

Fig. 35 Looking further, I find that, just as the picture's frame cannot quite contain the time and space of the lovers, nor can it contain their story. These indeterminacies are all of a piece with Tsering Nyandak's composition and brushwork, somewhat gnarly.

In classical Western art, a painting of lovers usually implies a narrative. But what's going on here is as ambiguous and striking as, say, a Max Beckmann. Embracing her with one burly arm, the man's attention is elsewhere, transfixed by a tiny yellow flower he reaches towards, in her hair (or has he just placed it there?). (Am I inserting Buddhist discourse where none is intended in recalling the story of the enlightenment of the Buddha's disciple Mahākāśyapa, attained by looking deeply at a flower in the Buddha's hand? Here's yet another case of representation carrying with it various possibilities of discourse and history. And compare the Buddha's holding up a flower to his disciples – with Jesus: "Behold, the lilies of the field…")

Fig. 36 Bare chested, his garb consists of a worker's cap and a pair of greyish work pants, patched at the knee and cinched with a black belt. The woman embraces him with one arm (her other arm unseen). She's barefoot and wears a red blouse. The colors of her seemingly traditional dress are damped down Her gaze seems both sensuous and wise. In a curious position, he sits within her wide-open lap, sideways, straddling one of her legs, with one of his legs folded over the other.

Looking longer, I notice the right bosom of the woman is fully exposed. Again, my brain can't help but secrete random thoughts. Is he too preoccupied by the tiny, delicate, five-petalled flower to reciprocate her soulful gaze? Or could this be before, or after, lovemaking? Maybe they're just enjoying getting out together? Then I stop, and think can't love be as indeterminate and sensuous as this? So vividly, monumentally immense with presence, yet gnarly.

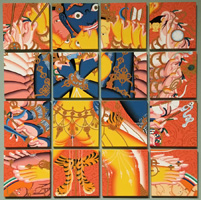

Fig. 37 Next to this sensuous, emotive narrative is a sharply contrasting work by Tsherin Sherpa (more about whom in a moment). Kalacakra may be easily described, although the effect challenges my lexicon. Here, the traditional iconography of yab-yum is cut up, permutated, and reassembled into a square composed of sixteen smaller squares (4x4). There's barely just enough continuity from some squares to others to lend a sense of coherence. Up top, the two deities' faces are in the same frame. Beneath their faces, their blue and orange bodies locate an approximate center, with auxiliary details against a red background. Yet, from one square to any adjacent square, there's more of a leap than any semblance of linear continuity. Adding to the fun is how each square has physical depth, casting a shadow – and is set next the each other with a slight space in between.

I remember, when he was residing in the Bay Area in 20016, a mural he displayed using this tactic. That piece was nine panels wide and six high; elsewhere he's displayed similar squares – six panels wide, nine high. Given a larger scale to work with, any continuity was even dicier, since the squares are on a different scale from each other. Here, and as we'll see next with his Red Protector, he's opening out the traditional painterly illusion of representation upon a two-dimensional surface to explore other possibilities, dimensions, dynamics, depths.

Post-Thankga

Raised in Kathmandu, Nepal, Tsherin Sherpa apprenticed with his father, celebrated thangka master Urgen Dorje, from the age of 12. How that training expresses itself today might be a benchmark for many of the choices contemporary Himalayan / Tibetan artists are facing in the international arena of art.

Having painted traditional, devotional, meditation icons for two decades, he's aware that when thangkas are created for Westerners, they sometimes become degraded to the level of kitsch. Arriving in the West, he absorbed such Western modernist and post-modernist influences as Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol. Around that time, he painted a commission of a thangka landscape featuring Jamba Juice in the center.

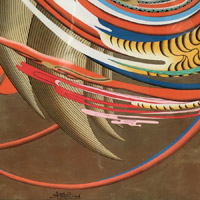

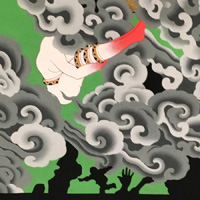

Fig. 38 On display is Red Protector (2015). As with Kalacakra, traditional imagery is still there, but reconfigured in startling new ways. It asks us to imagine what if a typically energetic protector deity were computer-scanned, digitally manipulated, and repainted in such altered form, using traditional pigments and also such nontraditional materials as acrylic and gold leaf.

On one level, this protector deity looks like it were put through a cyclotron, then sketched by a surreal cartoonist. (Sure enough, Tsherin Sherpa's work has been featured in Juxtapoz.) Another way of contextualizing this might be to consider how deity images in thangkas are used in practice, if my understanding is correct, as templates for a 3D visualization which ultimately dissolves into emptiness, the fertile void, (शून्यता, Sanskrit, sunyata; སྟོང་པོ་ཉིད, stong-pa nyid, Tibetan). Perhaps what we're glimpsing here is such merging with the fertile void, blank openness. It rigorously maintains its integrity from any viewing distance, or levels of scale. As with Kalacakra, it's not abstract. Instead, just as the moment of Cubism never jettisoned representationalism, it marks a critical departure towards a new reality.

Fig. 39 |

Fig. 40 |

Fig. 41 |

Fig. 42 |

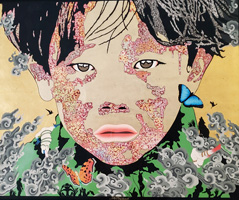

The gaze arrests me, as if silently asking, "What's going on? And why am I here?" To see what the gold boy sees, we must imagine what hells and hopes he's seen.

Fig. 43 |

Fig. 44 |

Fig. 45 |

Fig. 46 |

Beyond symbols, the painting connects with me at such a visceral level as to create a bond of vulnerability, beyond narrative.

Gasoline Cans

I'm close to where I came in. I'm near again to the colossal earth-touching Buddha, flanked by two contemporary Buddhas, one of which is aflame.

Fig. 47 |

Fig. 48 |

Fig. 49 |

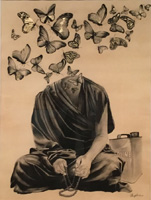

Fig. 50Emerging from the dynamics between luminous, limitless space and the funky, literal gas can … reference to an unseen event and its undeniable reality … – the whole set-up furnishes a perch for a lovely butterfly, gazing beyond the frame.

At first glance, it might seem offhand. Yet a butterfly is living proof of transformation. (This is not a metaphor, nor mere lyricism.) The butterfly appears in this artist's work as far back as 2008,when he first began painting nontraditional art. I see in it a marriage of Eastern and Western worldviews. Buddhists see reality as interdependent, everything intertwined. In the West, the "Butterfly Effect" is an example of Complexity Theory, showing how small perturbations can generate dynamic ripple effects. A small butterfly, flapping its wings in an Amazon rain forest, can trigger a chain reaction resulting in major storms in the Gulf of Mexico. At least, as with the breeze through prayer flags, so one can only hope.

Fig. 51 |

Fig. 52 |

Fig. 53 |

* * * * *

Once more, I'm at the door. BOUNDLESS renews my vision of what is possible, even immeasurable. What a rare and precious gift! May it benefit all beings.Gary Gach is an author, teacher, and literary translator. His most recent title is PAUSE … BREATHE … SMILE – Awakening Mindfulness When Meditation Is Not Enough (Sounds True; Tantor Media, audio edition). His previous book is The Complete Idiot's Guide to Buddhism. He also edited What Book!? – Buddha Poems from Beat to Hiphop. His work has been published in American Cinematographer, Art Week, The Atlantic, Harvard Divinity Bulletin, Kyoto Journal, Mānoa, The New Yorker, and Yoga Journal.

Author page: GaryGach.com

Bibliography

Three films by Pema Tseden: https://bit.ly/2GCAooW

Tsherin Sherpa's talk in conjunction with the exhibit: https://bit.ly/32YkwH3

McKenna, Phil. "Tibet is warming at twice global average." New Scientist. July 24, 2007 Mayhew, Bradley & Kelly, Robert. Lonely Planet Guide to Tibet. (p322). 9th edition. March 2015.

Exhibition Photos

Articles by Gary Gach

asianart.com | articles