The Sacred and the Profane - On the Representation of the first and second rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtus in Mongolian Buddhist Art

by Elisabeth Haderer, Center for Buddhist Studies/University of Hamburg

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions)

Preface

Fig. 1In recent time, significant progress has been made in the field of research on Tibetan art. Nevertheless, little is known about Buddhist art of Mongolia and Buryatia which was derived from Tibetan Buddhist art.

Like in Tibet, many ancient Buddhist artifacts fell prey to devastation over the centuries. Most of the art dating to the first dissemination of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia during the Yuan-dynasty (1279-1368) and earlier were destroyed in the uprisings after the fall of the Yuan. At the beginning of the 20th century, many of the Buddhist artefacts which had survived since the second dissemination of Buddhism in the 16th century were lost during disastrous ravages carried out by the Communist regime.

As a result, what remains is but a fraction of the wealth of materials produced in the cultural realm of Buddhist Mongolia. In spite of these acts of destruction, some exceptional painted scrolls (tib. thang ka) (figs. 4, 6, 7, 9-13), appliqués (tib. 'tshem drub; m. zeegt namal) (fig. 5) and bronzes (tib. sku 'dra) (figs. 2, 3, 8) have survived in the museums of Mongolia and Buryatia such as the Fine Arts Museum and the Bogdo Khan Palace Museum in Ulan Bator, the Historical Museum, Ulan Ude, and various other Russian and international collections.

Fig. 2One pioneer in the field of research on Mongolian Buddhist art was German scholar Siegbert Hummel, who investigated Mongolian artifacts belonging to the Leder[1The Bohemian natural scientist Hans Leder (1843-1921) brought back about 4000 Mongolian artifacts from his travels in Mongolia. He later sold these to ethnography museums in Austria (Vienna), Germany (Hamburg, Stuttgart, Heidelberg, Leipzig, Dresden), the Czech Republic (Prague, Opava) and Hungary (Budapest). The collection includes Buddhist objects such as thang kas, sculptures, miniature paintings (tib. tsa ka li), clay statuettes (tib. tsha tsha) and various ritual items. Some of the thang kas from the Leder Collection which are housed in ethnography museums in Vienna, Heidelberg, Hamburg, Leipzig, the Linden-Museum in Stuttgart, and the Néprajzi Múzeum in Budapest are discussed in Elisabeth Haderer, “Buddhistische Thangkamalerei in der Mongolei: Einige Rollbilder der Sammlung Leder” (Thesis, University of Graz, 2003).] Collection in the Linden-Museum in Stuttgart[2Siegbert Hummel, “Die lamaistischen Malereien und Bilddrucke des Linden-Museums,” in “Tribus: Veröffentlichungen des Linden-Museums”, special issue, no. 16 (1967).; ------, “Die lamaistischen Kultplastiken im Linden-Museum '1. Die lamaistischen Bronzen, 2. Die lamaistischen Plastiken aus Ton, Papiermaché und Holz',” Tribus: Veröffentlichungen des Linden-Museums, no. 11 (1962): 15-69; ------, “Die lamaistischen Miniaturen im Linden-Museum,” Tribus: Veröffentlichungen des Linden-Museums, no. 8 (1959): 15-39.]. In two volumes on Mongolian Buddhist paintings and bronzes[3N. Tsultem, Development of the Mongolian National Style Painting Mongol Zurag in Brief (Ulan Bator: State Publishing House, 1986).; ------, Mongolian Sculpture (Ulan Bator: State Publishing House, 1989).] Mongolian historian N. Tsultem provides a good overview on the styles and aesthetics of Mongolian Buddhist art by presenting some major works of art in Ulan Bator's museums. Two innovative and well researched contributions on Mongolian art are two American exhibition catalogues.[4Patricia Berger and Terese Tse Bartholomew, Mongolia: The Legacy of Chinggis Khan (San Francisco: Thames & Hudson, 1995).; Linda Komaroff and Stefano Carboni, ed., The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353 (New York: Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2002).] In addition, Krystyna Chabros published a key work on Mongolian decorative art and its symbolism.[5Krystyna Chabros, “The Decorative Art of Mongolia in Relation to other Aspects of Traditional Mongolian Culture,” Zentralasiatische Studien, no. 20 (1987): 250-81.] The latest research on representations of the rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtus, in particular the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu Zanabazar, is by Uranchimeg Tsultem and Elvira Eevr Djaltchinova-Malets who produced an exhibition on this topic.

Fig. 3Several elucidating articles on Tibetan lama portraiture have been published by Jane Casey Singer,[6Jane Casey Singer, “Early Portraiture Painting in Tibet,” http://www.asianart.com, 1996.] Heather Stoddard[7Heather Stoddard, “Fourteen Centuries of Tibetan Portraiture,” in Portraits of the Masters: Bronze Sculptures of the Tibetan Buddhist Lineages, ed. Donald Dinwiddie (Chicago: Serindia Publications, 2003), 16-61.] and Veronika Ronge[8Veronika Ronge, “Porträtdarstellungen der Tibetischen Könige zur Chos rgyal Zeit (8. - 9. Jh.),” in Das Bildnis in der Kunst des Orients, ed. Martin Kraatz (Stuttgart: Steiner, 1990), 175-81.].

The life stories of the rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtus have been translated and commented by scholars like Charles Bawden,[9Charles Bawden, “The Jebtsundampa Khutukhtus of Urga,” Asiatische Forschungen, no. 9 (1961).] Hans-Rainer Kämpfe,[10Hans-Rainer Kämpfe, “Sayin Qubitan-u Süsüg Terge: Biographie des 1. rJe bcun dampa-Qutuqtu Öndür gegen (1635-1723), written by Ṅag gi dbaṅ po 1839, 1. Folge,” Zentralasiatische Studien, no. 13 (1979): 93-108; Hans-Rainer Kämpfe, “Sayin Qubitan-u Süsüg Terge: Biographie des 1. rJe bcun dampa-Qutuqtu Öndür gegen (1635-1723), written by Ṅag gi dbaṅ po 1839, 2. Folge,” Zentralasiatische Studien, no. 15 (1981): 331-341.] and Aleksei Pozdneyev.[11Aleksei M. Podzneyev, Mongolia and the Mongols, ed. John R. Krueger (Bloomington: Uralic and Altaic Series, 1971), 61:319-393.]

Here, I will analyze some Mongolian portraits of the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu Blo bzang bstan pa'i rgyal mtshan (1635-1723), Zanabazar, and the second rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu Blo bzang bstan pa'i sgron me (1724-1757).[12The rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtus (mong. Bogdo Gegen) who were the highest Buddhist representatives in Outer Mongolia (Khalkha) since the 16th century. The first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu, Zanabazar (1635-1723), was the most important of the altogether nine incarnations (tib. sprul sku) which have been recognized until today.] First, I make an attempt to define their specific iconographic and physiognomic features. As I proceed, I am especially interested in whether these features are tied to written sources of the rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtus' hagiographies and whether it is possible to discern which prototypes the artists used for their representation. Second, I isolate stylistic features of the Mongolian and Buryatian paintings discussed.

Introduction

As in Tibetan Buddhist art, the portraiture of Buddhist teachers (tib. bla ma) and high Buddhist representatives was a favored subject within Mongolian and Buryatian art. In Tibetan Buddhism, the lama is referred to as a fully accomplished spiritual being, a Buddha (tib. sangs rgyas), and as the holder of the authentic teachings and meditation practices that have been passed from master to student since the time of the historical Buddha Śākyamuni (tib. sangs rgyas sha kya thub pa) (c. 560-478 B.C.). For this reason, the bodies of Tibetan Buddhist masters are traditionally depicted with the idealized features[13The 32 major and 80 minor marks of perfection, which are partly invisible.] of a Buddha. These features were defined in the classical Indian treatises on art such as the Citralakṣaṇa (tib. ri mo'i mtshan nyid [The Treatise on the Characteristics and Sources of Pictorial Art] (6th or 7th century A. D.) or the Mañjuśrīmūlakalpa (after 6th century). Although they have idealized bodies, Tibetan Buddhist masters are represented with individualized facial features. These specific physiognomic features along with their character traits[14 „...of all the children he [Zanabazar, the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu (1635-1723)] differed in that from birth he was a wholehearted and balanced being (...)” (Kämpfe, “Sayin Qubitan-u Süsüg Terge: 1. Folge,” 97.). ] were sometimes mentioned in written sources such as their spiritual biographies (tib. rnam thar), or they were transmitted orally from one generation of students to another[15In Mongolia, the biographies of the rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtus were compiled after the classical Tibetan rnam thar. In the 18th and 19th centuries many editions of their hagiographies were printed in Beijing and distributed among the Mongolians (Klaus Sagaster, “Der Buddhismus bei den Mongolen,” in Die Mongolen, ed. Walther Heissig (Innsbruck: Pinguin Verlag, 1989), 256-57.).].

Fig. 4 |

Fig. 4a |

Fig. 4b |

The artists often consulted these sources for the making of lama portraits. However, in most cases they stuck to the established iconography which was passed on in iconographic manuals.[16Examples for basic iconographical works which were used by Mongolian artists are: “All the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas” (chin. Zhufo pusa), dated 1431, “Three Hundred Icons”, which was compiled in the 18th century by the second lCang skya Khutukthu Rol pa'i rdo rje (1717-1786), or a text which was based on the work of the first/fourth Panchen Lama (tib. pan chen bla ma) bLo bzang chos kyi rgyal mtshan(1781-1852) were consulted.] In addition to that, outstanding works of art known as nga 'dra ma [literally “just like myself”], [i.e., a good likeness of myself][17This type of portrait was made of a Buddhist master when he was still alive and confirmed by him as a “good likeness” after life (Stoddard, “Fourteen Centuries of Tibetan Portraiture,” 32.).] or nga 'dra ma phyag mdzad [self-portrait] served as visual guidelines. A further prototype were the mummified bodies (tib. dmar gdungs [flesh-embodiment]) of dead Buddhist masters.[18The mummification and treatment of corpses seems to date back to the end of the 6th century A. D. (Doris Croissant, “Ahneneffigies und Reliquienportät in der Porträtplastik Chinas und Japans,” in Das Bildnis in der Kunst des Orients, ed. Martin Kraatz, ed. Martin Kraatz (Stuttgart: Steiner, 1990), 235, 238.).]

“Of the Urga Gegens, the first and fourth khubilgans [sprul sku] are preserved in Amur-bayaskhulangtu monastery, the second and sixth in Shajini-badaragulukchi monastery, and the third, fifth, and seventh in the Gandan in Urga. All of these were interred in a sitting posture and differ from one another only in the position of their hands. The Öndur-gegen is interred holding a vashir [rdo rje] and a khonkho (bell) in his hands; the second Gegen is represented giving a benediction with his right hand; the third is holding a bumba [vase] on his knees in both hands; the fifth is holding a book.”[19Pozdneyev, Mongolia and the Mongols, 386.]

As far as Mongolian Buddhist lama portraiture is concerned, Mongolian artists mainly followed Tibetan models. The Tibetans had adopted the Chinese tradition[20In China, the art of portrayal dates back to the Han time (206 B.C to 220 A.C.) and was perfected in T'ang-time (618- 907) (Dietrich Seckel, “Die Darstellungs-Modi des En-Face, Halbprofils und Profils im Ostasiatischen Porträt,” in Das Bildnis in der Kunst des Orients, ed. Martin Kraatz (Stuttgart: Steiner, 1990), 205.).] of portraying the likenesses of the faces of Buddhist masters. However, for the depiction of their bodies, they followed the iconographic conventions.[21Hummel, “Lamaistische Malereien,” 21.] In order to achieve lifelike resemblances, Mongolian and Tibetan artists often relied on monks or common people as models.[22Hummel, “Lamaistische Malereien,” 44.

When the first Buddhist temple of Tibet, bSam yas, was built in 779, portraits of several Tibetans were made to convey a look for the different Buddha forms depicted in it: “From among the assembly of Tibetans, the handsome man call sTag tshab of Khu was taken as a model and an image of Lord Aryapalo was made; the beautiful woman Bu chung of lCog ro was taken as a model and the Goddess 'Od zer can was made on the left; the beautiful woman Lha bu sman of lCog ro was taken as a model, and Tārā was made on the right” (Ronge, “Porträtdarstellungen der Tibetischen Könige,” 178.; Stoddard, “Fourteen Centuries of Tibetan Portraiture,” 22.).]

Since the 18th century the famous Narthang (tib. snar thang) woodblocks[23The Narthang-portraits are said to be based on a thang ka set which is ascribed to the Tibetan master-painter and portraitist Chos dbyings rgya mtsho who flourished in the mid-17th century in the central Tibetan province of gTsang. He was renowned for his highly realistic and expressive style he employed for the faces and postures of the figures in particular. (David Jackson, A History of Tibetan Painting: the great Tibetan painters and their traditions (Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1996), 219-43.).] which depicted the Dalai and Panchen Lamas provided an important iconographic source for lama representations in Mongolian art. Following their production, which scholars estimate to have occurred in 1737,[24Marilyn M. Rhie and Robert A. F. Thurman, Worlds of Transformation: Tibetan art of wisdom and compassion (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999), 363.] many copies of this series have been made and disseminated as far as Beijing.[25Patricia Berger, “Lineages of Form: Buddhist Portraiture in the Manchu Court,” The Tibet Journal, vol. 27, no. 1-2 (2002):120.; Michael Henss, “Vom rechten Maß und richtiger Zahl: Die Ikonometrie in der buddhistischen Kunst Tibets,” in Tibet: Klöster öffnen ihre Schatzkammern (Berlin: Hirmer, 2007), 245.]

Besides traditional Buddhist painting and sculpture, the production of embroidered thang kas, which are produced by appliqué[26Pieces of cloth are glued or stitched on an underlay.] gained wide popularity in Mongolian Buddhist art. [27In Mongolia, the art of appliqué (m. zeegt namal, “what is glued with sewed border”) is said to have been applied for the first time by the Xiongnu people (c. third to first century B. C.). The appliqué was further improved during the Yuan period (1278-1368) and later perfected by Buddhist lama artists. Nevertheless, the art of appliqué is not a traditional Mongolian craft and has not been practised outside of Buddhist monasteries since the mid-20th century. Compared to paintings and bronzes, embroidered works of art are relatively rare (Krystyna Chabros, “Der Gebrauch der Applikationstechnik bei der Thanka-Herstellung,” in Die Mongolen, ed. Walther Heissig (Innsbruck: Pinguin Verlag, 1989), 184.). According to Watt and Wardwell, for the Mongols “textiles were a higher form of the plastic arts than painting or sculpture” (James C. Y. Watt and Anne E. Wardwell, When Silk was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997), 5.).]

“In China under the Yuan, a clear relationship linked silk tapestry and other patterned silks with painted portraits. Painted portraits served as models or cartoons for woven versions, which the Mongols evidently preferred. This must have been the case with the royal portraits in the lower corners of the Yamantaka Mandala silk tapestry (...) The well-known painted imperial portraits of Khubilai Khan and his consort Chabi (...) were very likely reproduced as woven images for a Lamaist Buddhist shrine.”[28Linda Komaroff, “The Transmission and Dissemination of a New Visual Language,” in The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353, ed. Linda Komaroff and Stefano Carboni (New York: Yale University Press, 2002), 183.]

Early Mongolian Buddhist art was influenced to a great extent by the art of the Central Asian Uygurs, who had emerged by the 6th century A.D. As it was the case with early Tibetan art during the 13th and 14th centuries, early Mongolian Buddhist art was predominantly inspired by Nepalese and Indian traditions. Besides that, it drew inspiration from the Chinese art of the Yuan (1279-1368) and Ming (1368-1644) dynasties. Later in the 16th century, when Tibetan Buddhism came to Mongolia for the second time, various Tibetan art traditions emerged. Among the more important are the Menri- (tib. sman ris), which can be traced back to some time in the mid-15th century; the Khyenri (tib. mkhyen ris) from the 15th and 16th centuries; and the Karma Gardri (tib. karma sgar bris) tradition from the end of the 16th century. All of these traditions found their way into Mongolian Buddhist art.

Over the course of time, a distinctive Mongolian Buddhist art tradition with different regional styles developed. Due to its geographical position, the Buddhist art of Outer Mongolia was more influenced by Tibetan art, while Inner Mongolian Buddhist art mainly followed Chinese art traditions. In addition, many elements of Mongolian folk art, which is deeply rooted in Shamanism, merged with the Buddhist art in Mongolia.

Some Portraits of the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu

The first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu Zanabazar (tib. rang byung ye shes rdo rje; blo bzang bstan pa'i rgyal mtshan)[29In Mongolian: Öber-iyen ɤaruɤsan belge bilig-ün bčir, or Ödnür gegen (Kämpfe, “Sayin Qubitan-u Süsüg Terge: 1. Folge”, 105.); “One day the emperor came to visit the saint [Zanabazar] in his private yurt...Besides that, he imparted on him the title “Enlightened teacher, rJe btsun dam pa bla ma”. (Kämpfe,“Sayin Qubitan-u Süsüg Terge: 2. Folge”, p. 331.).] (1635-1723) was born as the son of an influential Outer Mongolian Khan, the Khalkha prince Gombo Dorje (1594-1655), in 1635. Soon, the child was confirmed by the fifth Dalai Lama Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho (1617-1682) and the first/fourth[30There exist two different systems of counting the Panchen Lamas. Some regard mKhas grub dge legs rnam rgyal dpal bzang (1385-1438) as the first Panchen Lama, although he has been recognized as such until after his death. Others regard Blo bzang chos kyi rgyal mtshan (1567/1570-1662) as the first Panchen Lama, because he was the first one who was awarded the official title of a Panchen Lama. According to one of the counting systems, Blo bzang chos kyi rgyal mtshan (1567/1570-1662) is the first Panchen Lama, according to the other he is already the fourth. (see Fabienne Jagou, “Panchen Lama und Dalai Lama: Eine Umstrittene Lehrer-Schüler-Beziehung,” in Die Dalai Lamas: Tibets Reinkarnationen des Bodhisattvas Avalokiteśvara, ed. Martin Brauen (Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2005), 202-11, 210.] Panchen Lama Blo bzang chos kyi rgyal mtshan (1567-1662) to be the incarnation of the great Tibetan historian and Buddhist master of the Sa skya Jo nang-school, Tāranātha (tib. kun dga' snying po)[31Tāranātha was an important lineage-holder of the Jo nang tradition, originally an important branch of the Tibetan Buddhist Sa skya school,and an adherent of the gzhan stong (“empty of other”)-philosophy. He strongly opposed the Gelug pa tradition, whose representatives confiscated his monastery Jo nang after his death. His silver reliquary stūpa was sacked and the printing plates with his writings were sealed (David Jackson, “Spuren Tāranāthas und seiner Präexistenzen: Malereien aus der Jo nang pa-Schule des tibetischen Buddhismus,” in Die Welt des tibetischen Buddhismus, ed. Wulf Köpke and Bernd Schmelz (Hamburg, 2005), 612-13.).] (1575-1634). Both the fifth Dalai Lama and the first/fourth Panchen Lama became his teachers.

From his biography we learn that Zanabazar was known as an accomplished meditation master and a great scholar who invented a new Mongolian alphabetical system known as “soyombo”. According to oral tradition, he was an exceptional artist. A series of very finely worked Buddha bronzes in an Indian-Nepalese inspired style are attributed to him. He is reported to have had a consort for his tantric practice who was a gifted sculptor as well. She died young, at the age of eighteen, and legend has it that Zanabazar modeled several of his Tārā statues after her. In addition to his creative contributions, Zanabazar played quite an important political role. As an intimate and close friend of the Chinese emperor Kangxi (r. 1662-1722), he became an important mediator between the Mongols, the Chinese, the Tibetans, and the Russians.

Due to Zanabazar's popularity, many portraits have been made of him - a tradition that continues today. According to A. M. Pozdneyev the first portrait of Zanabazar was not made until 1798.[32When the fourth rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu Blo bzang thub bstan dbang phyug (1775-1813) visited Amarbayasgalant Monastery, he had the suburgan (reliquary stupā), which housed Zanabazar's embalmed body, opened. Then, he ordered his best artists to portray the corpse. This portrait served as a model of a cast image (Berger and Bartholomew, Legacy of Chinggis Khan, 266; Pozdneyev, Mongolia and the Mongols, 355; Kämpfe, “Sayin Qubitan-u Süsüg Terge: 2. Folge,” 338-39.]

Pozdneyev also mentions that when the Chinese emperor Kangxi (r. 1662-1722) learned that Zanabazar had died, he “sent the Urga lamas as a gift a portrait of this Gegen made of him by Chinese painters at the time the Gegen was still in Jehol.”[33Pozdneyev, Mongolia and the Mongols, 354.]

Iconographic Prototypes of the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu

Comparisons of the following portraits of the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu reveal that there exist several iconographic types for his representation in Mongolian Buddhist art.

Iconographic prototype 1

In general, the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu is depicted with a bald head or receding black hair, a broad face, and a mustache.[34In some representations the mustache is missing, or it is implied by two black spots on the left and right sides of the mouth (figs. 4, 7).] Apart from that, his facial expression is clear, determined, and compassionate.

In his right hand, raised to the level of his heart, he holds a diamond scepter (skt. vajra; tib. rdo rje). In his left hand, which rests in his lap in the gesture of meditation (skt. dhyānamudrā; tib. mnyam bzhag phyag rgya), he holds a bell (skt. ghānṭā; tib. dril bu). He sits in a complete posture of meditation (skt. vajrāsana; tib. rdo rje gdan) and is dressed in the threefold monk's robes[35The lower cloth (tib. mthang gos), the other cloth (tib. bla gos), which is worn over the lower cloth, and the half skirt (tib. sham thab) or shawl (A. B. Griswold, “Prolegomena to the Study of the Buddha’s Dress in Chinese Sculpture,” Artibus Asiae, vol. 26 (1963): 85-131.).] that signify his buddhahood (figs. 2, 4-8).

Fig. 5 |

Fig. 5a |

Fig. 6 |

Fig. 6a |

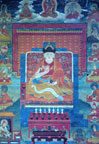

This iconographic prototype was most probably derived from the representation of Tāranātha (fig. 1). The latter is often represented with the same attributes, a rdo rje and a bell, which refer to his mastery of tantric practice.

Iconographic prototype 2

In some images (fig. 3) the rdo rje, Zanabazar holds in his right hand is replaced by a gesture of granting refuge (skt. śaraṇagamana-mudrā; tib. skyabs sbyin gyi phyag rgya).

Iconographic prototype 3

In many paintings Zanabazar is represented en-face, sitting on a throne in a hilly landscape. In some cases, he is surrounded by the figures of his previous incarnations[36For a detailed description of the single figures see Jackson, “Spuren Tāranāthas und seiner Präexistenzen,” 611-65.] (figs. 4, 7), which are arranged on a smaller scale at the sides and across the top of the composition.

Fig. 7 |

Fig. 7a |

Fig. 7b |

Fig. 8 |

In fig. 4, Zanabazar sits on a high throne construction that is supported by two lions with unusually long legs and open mouths. The top of the throne construction is of vaulted shape and covered with a red cloth. The upper part of the throne pedestal is framed by a low balustrade. The sides of the throne are reduced in their perspective, thus creating a three-dimensional effect. The backrest of Zanabazar's throne seat is decorated with a blue cloth that is adorned with a golden pattern of dotted flower-tendrils and an honor scarf (tib. kha btags). Blue color is also used for the lining of Zanabazar's coat, for the mid-section of the throne pedestal, and for the clothes and sitting cushions of the side figures. The side figures are arranged in two vertical lines at the sides of the painting sitting within a spacious landscape of triangular hills that are outlined by dark-green plants. Some of the figures appear sitting on clouds in the sky on the left and right sides of the Buddha of Limitless Light, Amitābha (tib. 'Od dpag med), with whom the lineage starts. In front of the throne is an offering including the eight auspicious symbols (skt. aṣṭamaṃgala, tib. bkra shis rtags brgyad) and the offer of the five senses.

Zanabazar is depicted with a bald, round head (fig. 4a). He has youthful facial features[37Jackson notes that in Tibetan and Mongolian Buddhist art it was common to depict an elder lama with youthful features as an auspicious symbol for his long life (Jackson, “Spuren Tāranāthas und seiner Präexistenzen,” 644.).], a high forehead and narrow eyes. His eyes seem to be blue although the color has vanished. His mouth is small with thick lips and a mustache is implied by two fine black dots at the sides. He has long ears that stick out. Surprisingly, the halo which normally surrounds the heads of high lamas is missing here.

In simpler compositions the side figures of his previous incarnations have sometimes been omitted. Instead, Zanabazar is flanked by two monks standing at the left and right side of his throne. They are shown bringing offerings and ritual implements to a small table in front of the throne (fig. 5).

In the embroidered thang ka Zanabazar is sitting on two cushions. The backrest of the seat is covered with a blue cloth that is decorated with Chinese shou characters symbolizing long life. Shou characters also adorn the thang ka mounted on an honor parasol above Zanabazar's head. The thang ka depicts the first/fourth Panchen Lama, Zanabazar's teacher. The uniformly dark blue sky is filled with rainbow-hued clouds. Zanabazar is surrounded by a peach-colored body halo and a gray-colored head halo. Behind him we can spot big-leafed plants with peach-like fruits. In the left bottom corner a bareheaded old monk is shown in full profile - which is very rare - carrying a golden vase of long life (skt. jīvana-kalaśa; tib. tshe bum) with a flaming jewel (skt. ratna; tib. rin chen). In the right bottom corner stands a young, black-haired monk with characteristically Mongolian features, portrayed in a semi-profile and holding a rice maṇḍala (tib. dkyil 'khor) in his hands. In front of the throne stands a small compact table with a Tibetan inscription: “rJe bstan pa'i rgyal mtshan la na mo”, meaning “Homage to rJe [btsun dam pa] bstan pa'i rgyal tshan”. On the table in front, there is a double drum (tib. da ma ru), a bell (tib. dril bu) with a dharma wheel as a finial, a vessel with yoghurt (?) and a round bowl with similarly white content.

In very simple compositions, Zanabazar is depicted as the main figure without any side figures.[38Bawden, “Some Portraits of the Jebtsundampa Qutuγtu,” 183-95.]

In fig. 6, Zanabazar sits on a pile of colorful cushions on a plain, orange-colored throne pedestal that is decorated with patterns of golden spirals and a white cloth. On the right there is a red-colored staircase for mounting the throne. On the left side of the throne stands a small offering table painted from above. Different objects such as a water flask (skt. kalaśa; tib. spyi blugs), a double-drum, a flaming jewel and a blue bowl are arranged in a row.[39For the different combinations of offerings and ritual objects see Bawden, “Some Portraits of the Jebtsundampa Qutuγtu,” 186-87.] In front of the throne pedestal stands a big blue bowl with an offering of the five senses among which are three peaches. The upper background consists of three frame-like panels that are arranged one by one. The first panel is ultramarine blue and lined on each side and at the top by several rows of cuttings, which indicate an honor parasol. The pink and white shades of the second panel are reflected in the head halo of Zanabazar, in the upper cloth covering the sitting cushions, and on the surface of the side table. The fiery orange-red color of the outer panel is mirrored in Zanabazar's outer robe and the throne pedestal. The yellow color of his coat is also used for the upper cushion and in the drapery of the inner panel. The same mint-green color of the head halo is applied for the hilly landscape in the background. As in fig. 4, the hills are outlined with dark green dotted plants.

Zanabazar holds his head slightly to the side (fig. 6a). He has young facial features, a broad nose, long ears, and accentuated lips. The corners of his mouth are turned upwards, conveying the impression a smile. His eyes are arranged in close distance to each other, as shown in fig. 4. He has black receding hair forming a tonsure at the top of his head. Despite the stylized facial features, his expression comes across as individual and intimate.

Iconographic prototype 4

In fig. 9, Zanabazar is depicted en face as an elderly person. This is indicated by the wrinkles and fine lines on his forehead and around his cheeks and chin (fig. 9a). He has short black hair. His face is broad with a pointed chin, slit eyes, long ears, and a small smiling mouth. His expression is stern and powerful. He wears a Mongolian-style red dress with a black hem that is adorned with a pattern of golden flowers and crosses.[40“In the eleventh month he went together with the Grub čhen-u qubilɣan Blo bzan bstaṅ 'jin [first Bogdo Gegen] to Šar ka in order to consecrate the sanctuaries, which had been donated by the mother of the previous [Chinese] emperor, or in her honor. For this event the emperor equipped him with a complete lama's dress including hat and boots of the greatest splendor.” (Kämpfe, “Sayin Qubitan-u Süsüg Terge: 2. Folge,” 331.). ] As in fig. 4, body and head halos are missing. Zanabazar sits on a pile of small cushions and a red cloth, which is put in view from above. The seat is placed inside an unusual red and blue niche-like throne construction, which is decorated with small cuts of drapery at the sides and a golden scepter on top. The top of the seat backrest is of manifold vaulted shape and decorated with a stylized flower pattern in many colors on yellow ground. Both sides of the throne are overgrown with plant tendrils with big pointed green and blue leaves, elaborate pink peony flowers, and peach fruits. The landscape in the background consists of pointed triangular hills, which are outlined by dark green plants and pinkish clouds.[41Patricia Berger notes that this special way of painting the hills and also the depiction of the big peony flowers were a specialty of the lama-artists working at the Manchu summFor the iconographic identification of the Dalai Lamas see Micheal Henss, “Die Ikonographie der Dalai Lamas,” in Die Dalai Lamas: Tibets Reinkarnationen des Bodhisattvas Avalokiteśvara, ed. Martin Brauen (Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2005), 262-77. er court in Jehol (Chengde). This evidence, according to Berger, suggests that the portrait of Zanabazar was painted by artists working at the Manchu court when Zanabazar visited Dolonnor and Beijing in 1691 (Berger and Bartholomew, Legacy of Chinggis Khan, 123-24).] In front of the throne stands an offering table, which is covered by a rose-colored table cloth with a golden Chinese cloud pattern. The sides of the table are reduced in their perspective and the offering bowls and ritual objects are neatly arranged in two rows.

Fig. 9 |

Fig. 9a |

Fig. 9b |

Fig. 9c |

In both hands, Zanabazar holds a Tibetan book (tib. po ti, dpe cha), which can be understood as a reference to his merits as a great scholar.[42In a more subtle spiritual context the book can also refer to the bodhisattva of wisdom, Mañjuśrī (tib. 'Jam dpal dbyangs), or even to Tāranātha, or one of his previous existences (Jackson, “Spuren Tāranāthas und seiner Präexistenzen,” 627, 629, 653).] His activity as an artist is implied by the presence of Sarasvatī (tib. dByangs can ma) (second figure on the upper left side), who is theconsort of the wisdom bodhisattva Mañjuśrī andthe embodiment of artistic inspiration. In the sky above appear the Zanabazar's teachers, the first/fourth Panchen Lama (left) and the fifth Dalai Lama (right),[43For the iconographic identification of the Dalai Lamas see Micheal Henss, “Die Ikonographie der Dalai Lamas,” in Die Dalai Lamas: Tibets Reinkarnationen des Bodhisattvas Avalokiteśvara, ed. Martin Brauen (Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2005), 262-77. ] and Vajrasattva (tib. rDo rje sems pa) in union with his consort (in the middle).[44Vajrasattva/Vajradhara (tib. rDo rje chang) were closely linked to Zanabazar and Tāranātha respectively who are often depicted holding the attributes of these Buddha aspects, the vajra and the bell (Berger and Bartholomew, Legacy of Chinggis Khan, 123). Although it might be Vajrasattva in union who is depicted here, the iconography is very unusual. Instead of the rdo rje and the bell he holds two golden vessels in his hands. Moreover, his partner is not blue as usual, but white and holds two skull cups (skt. kapāla; tib. thod pa, ka pa la) instead of one skull cup and a chopping knife (skt. kartari; tib. gri gug) in her hands.] At the bottom of the painting three protective Buddha forms are represented: the standing blue six-armed Mahākāla (skt. Ṣaḍbhuja Mahākāla; tib. mGon po phyag drug pa) (left), the yellow Vaiśravaṇa (tib. rNam thos sras) (middle) on a lion,[45He is the guardian of the north and the protector of wealth.] and the white standing Mahākāla (skt. Ṣaḍbhuja Sita Mahākāla; tib. mGon po yid bzhin nor bu) (right).[46He is regarded as one of the main protectors of wealth in Mongolia.] The yellow female Buddha form on top of the right-hand side is Vasudhara, who symbolizes abundance.[47Berger and Bartholomew, Legacy of Chinggis Khan, 123.]

A very interesting detail of the thang ka are the white line drawings of two stūpas at the left and right side in the lower part of the painting: a Parinirvāṇa stūpa (tib. myang 'das mchod rten) (left) (fig. 9b), symbolizing the death of Buddha, and an Enlightenment stūpa (tib. byang chub mchod rten) (right) (fig. 9c), standing - as the term implies - for Buddha's enlightenment.[48I want to thank Mrs. Eva Preschern for helping to identify the stūpa forms (Eva Preschern, “Visual Expressions of Buddhism in Contemporary Society: Tibetan Stūpas built by the Karma Kagyu Organisations in Europe” (PhD diss., Christ Church University Canterbury, forthcoming).]

Iconographic prototype 5

In some paintings and sculptures, Zanabazar is shown wearing a black fur (?) hat (figs. 7, 7a, 8). This hat consists of several parts that have the shape of lotus petals (?) and are sometimes outlined in red color (fig. 8), and a cone-shaped golden bump in the middle which is crowned by a golden half rdo rje.

The composition in fig. 7 unites various elements of the different iconographic prototypes discussed (figs. 4, 6, 8). As in figs. 6 and 9, Zanabazar sits on a throne, which is presented from above. The backrest of the seat is decorated with stylized flower patterns (fig. 9) and the offering table with the neatly arranged objects in front of the throne resembles that of fig. 9. The throne construction consisting of several panels in the background and the placement of the Mongolian-style red offering table to the side can also be found in fig. 6. In addition, another small Chinese-style lacquer table, on which the offerings of the five senses are arranged, stands in the center of the foreground. The hills in the landscape are once again outlined by plants that look like bushes and fir trees (figs. 4, 6).

The figures of the previous existences of Tāranātha are arranged at both sides of the painting and in the skies (fig. 4). Other than in fig. 4 the line starts with Cakrasaṃvara (tib. Khor lo bde mchog) and Vajravārāhī (tib. rDo rje phag mo) in union. Tāranātha is depicted second to the last figure on the bottom right side of the painting. He wears the characteristic, red, pointed paṇḍita hat which is typical of his iconography. Besides that, he performs the gesture of turning the wheel of the dharma (skt. dharmacakra-mudrā; tib. chos kyi ‘khor lo’i phyag rgya) and holds a lotus with a book in his left hand. The last figure in the line wears a yellow paṇḍita hat and holds a vase with the nectar of long life (skt.jīvana-kalaśa; tib. tshe bum) and two lotus flowers in its hands, which both rest in a meditation gesture in his lap. David Jackson suggests that this figure also represents the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu although the figure shows iconographic features that are quite unconventional for the depiction of Zanabazar.[49The iconographic features are also used for the representation of Tāranātha (Jackson, “Spuren Tāranāthas und seiner Präexistenzen,” 611-65.).]

Some Portraits of the second rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu

Like the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu, the second rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu Blo bzang bstan pa'i sgron me (1724-1757) was born as the son of a noble Khalkha clan.

“His father, Darkhan Chingwang, was raised in Beijing and twice married to Chinese princesses, but it was his Khalkha wife, who bore the incarnation of Zanabazar. As a child, he spent most of his time in Dolonnor, waiting out the Zunghar wars and Khalkha unrest. Even so, during his lifetime, the wealth and shabinar (serfs) of the Urga seat grew immensely, so much so that in 1754, the Qianlong emperor appointed a shangzudba (treasurer) to oversee the prelate's secular affairs, insisting that the Bogdo Gegen spend his time in study and prayer. He died of smallpox in 1757, after assuming the form of a fierce guardian and magically quelling an outbreak of the disease in the khüree [settlement] itself.[50Berger and Bartholomew, Legacy of Chinggis Khan, 70.]”

Iconographic prototype 1

In most representations (figs. 10-12), the second rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu is depicted wearing a yellow paṇḍita cap with side-flaps. This is the characteristic headgear for the Buddhist representatives of the Tibetan dGelugs pa tradition. In his left hand, which rests in his lap in the gesture of meditation, he holds a begging bowl (skt. pātra; tib. lhung bzed). With his right hand he performs the gesture of granting refuge at his heart. In addition, he holds two lotus flowers in his hands on which a rdo rje (right side) and a bell (left side) rest. He has a youthful appearance (figs. 10b, 11c, 12c).

Fig. 10 |

Fig. 10a |

Fig. 10b |

Fig. 11 |

Fig. 11a |

Fig. 11b |

Fig. 11c |

In fig. 10 the second rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu is surrounded by the previous incarnations of Tāranātha. Tāranātha himself is represented as the second to last figure on the right side of the painting (fig. 4b, 10a). He is portrayed with a red paṇḍita hat and he performs the gesture of turning the wheel of the dharma. In addition, he holds a long-stemmed lotus flower in his right hand topped with a book and a flaming jewel. The last figure of the line resembles that in fig. 7 and it might be again Zanabazar, who is depicted here. The figure wears a yellow hat and both hands are folded in meditation gesture in its lap while holding a vase with the nectar and the tree of long life and two lotus flowers with a bell and a rdo rje on their petals.

Fig. 12 |

Fig. 12a |

Fig. 12b |

Fig. 12c |

The landscape of flat triangular hills that are outlined by exactly drawn plants and trees is similar to the one in fig. 7. The sky is uniformly blue and filled with rainbow-hued clouds. The second Bogdo Gegen sits on a lotus throne and a moon disc. The alternately green and blue petals of the lotus throne are two-fold and lobe shaped. In between, one can spot bunches of colorful stamen. The lotus throne rests on a simple pedestal which is colored red and blue and decorated with an orange-blue drapery. In a depression at the front of the pedestal, there are two small white lions with long beards. Each lion holds a pink jewel in its paw. As in some portraits of the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukthu (figs. 6, 9) the throne is viewed from above. In the lake in front of the throne a pink-branched lotus flower grows with pointed green and blue leaves on which an orange bowl with various offerings rests. Among the latter, the three mint-green and brown dotted peach-like fruits in particular stand out (figs. 6, 11). The exuberant fiery-orange lotus flowers somehow recall the peony motif in fig. 9. On top of the tree, a wide-open, orange lotus blossom holds another lotus throne of pink petals on which Cakrasaṃvara and Vajravārāhī are standing in union.

The second Bogdo Gegen is represented en-face and from his body fine golden rays emanate (fig. 10b). He is surrounded by a blue head halo and a dark blue and peach-colored body halo. His red half-skirt is adorned with a scattered pattern of golden dotted and cross-like flowers (fig. 9, 13). He has a youthful oval face with a high forehead and narrowly arranged eyes. His gaze is slightly turned upwards while he is focusing the viewer. Moreover, he has a broad nose and a small smiling mouth with full lips.

Iconographic prototype 2

The portrait of the second Bogdo Gegen in fig. 11 shows iconographic and compositional features identical to fig. 10, implying that the same iconographic prototype has been used as a model for both paintings.

Other than in fig. 10, three scenes of the second Bogdo Gegen's life are depicted in the background.

The scene on the left (fig. 11a) shows the father of the second Bogdo Gegen, Darkhan Chingwang, who is depicted wearing a brown Mongolian costume and a mustache. He is sitting in front of a settlement of yurts next to his wife who wears the colorful costume and characteristic make up of Mongolian women and holds her baby in her arms. They look up into the sky where the child is pointing with its finger. There the eight-armed, eleven-headed form of sPyan ras gzigs (skt. Ekādaśamukha; tib. Thugs rje chen po bcu gcig zhal) appears surrounded by a red body halo (fig. 11). This gesture recalls a moment in the biography of the second Bogdo Gegen. The text mentions that the Bogdo Gegen's father was once sitting near his yurt holding the baby (the second Bogdo Gegen to be) in his arms. Suddenly the baby shouted: “There in the sky, in a rainbow, Mañjuśrī and Avalokiteśvara are moving!”, and Darkhan Chingwang looking up into the sky saw these bodhisattvas.[51Pozdeyev, Mongolia and the Mongols, 341.]

In the scene on the right side (fig. 11b) the father is shown again, this time wearing a blue Mongolian dress. He looks up to the sky and has put together his hands in the gesture of veneration (skt. añjali; tib. thal mo sbyar ba). Next to him stands a figure that is clad in red-orange robes - most probably a lama - holding the baby Bogdo Gegen in his arms. The baby also wears a yellow dress - possibly signaling his status as a high incarnation - and is standing up, pointing to the sky where the bodhisattva of wisdom, Mañjuśrī, appears.

Below the first scene on the left side (fig. 11a) another event is shown. A person clad in fine yellow Mongolian clothes hands over a Tibetan text (?) which is labeled twice with the Tibetan letter “ka” (?) to a person in a blue dress shown from behind.

This scene might illustrate the moment when the delegates of the Chinese emperor arrived to Kalkha in 1725. They informed the Khalkha Mongols that the Yongzheng emperor (1722-1735) had confirmed the son of Darkhan Chingwang as the incarnation of Zanabazar[52Pozdeyev, Mongolia and the Mongols, 341.] after consulting the Dalai and Panchen Lamas in Tibet.

If this is a depiction of the actual scene, the man with the text standing on the left side might be one of the Chinese emperor's delegates and the other figure Darkhan Chingwang.

Compared to fig. 5, the figure of a Panchen Lama - probably the second/fifth Panchen Lama bLo bzang ye shes (1663-1737) or the first/fourth Panchen Lama - is depicted sitting on a white lotus throne which rests in the big orange lotus blossom growing in the tree behind the throne. In the top right corner appears the dharma protector (skt. dharmapāla; tib. chos skyong) Yamāntaka (tib. gShin rje gshed) and in the bottom left and right corners Yama (tib. gShin rje) and Dhala (tib. dGra lha).

As far as the style of painting is concerned, the color application is transparent and light as in watercolor painting - an effect that might be due to the damages in some parts of the painting. The technique of shading is particularly applied in the lotus petals of the figures' thrones and in the pink-white head halos of the second Bogdo Gegen and of Avalokiteśvara in the top left corner. The outlines are drawn in a sketchy graphical style that becomes especially obvious in the contours of the Bogdo Gegen's yellow coat and in the flames surrounding the figure of Yama. A spatial effect is created by the staggered arrangement of the landscape in the middle-ground. The hills covered with trees and the rivers are painted in a very naturalistic style.

The hands and feet of the Bogdo Gegen and the continuing plant pattern at the hem of his yellow coat are carried out in a very careful way. Nevertheless, his eyes seem to be unfinished, or the color has flaked off. The left eyebrow was even emphasized by a thicker brush stroke. The shape of the face is broader and the eyes are larger than in fig. 10. Furthermore, his black hair sticks out from beneath his hat.

In fig. 12, the same composition scheme as in fig. 11 has been applied, but the stylistic completion is different. The dominating colors are brown and ochre shades. The composition is highlighted by the strong white-pink shade which is used for all the lotus flowers, the skin of the main figure's face and the head halo of Avalokiteśvara. In addition, golden outlines accentuate the leaves, the rays in the halos, the flames of the protective Buddha forms, and the patterns of the clothes, the throne pedestal and the yurts' roofs. The figures are outlined in an imprecise bold manner and emphasis is put on the dynamic pattern of swirls and flowers covering the figures' clothes, the throne drapery, and on the sun discs on which the protective Buddha forms are standing. The dark green plants covering the hills in the background (figs. 11) are applied loosely. As a whole, the composition conveys a naïve, at the same time “abstract” and unconventional impression.

Fig. 13In the painting from Buryatia in fig. 13 the second Bogdo Gegen is represented with the characteristic iconographic attributes, but with the portrait features that are common for the depiction of the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu. He is shown as an elderly person (fig. 13a) with wrinkles on his forehead and around his eyes and cheeks and with thin lips. He has a bald head, a head bump and receding black hair. His ears are long and stick out, his eyebrows are curved, and his upper-eyelid is rolling.

Fig. 13aThe second Bogdo Gegen sits on two oblong cushions on a throne pedestal which is defined by very exact outlines and the perspective is reduced on both sides. The front of the pedestal is decorated with a thang ka-like hanging made of blue and gold cloth. It is adorned with a Chinese mushroom-cloud (chin. rúyì)[53In Chinese art the rúyì-form symbolizes good luck and bliss (Josef Guter, Lexikon der Götter und Symbole der Alten Chinesen: Handbuch der mystischen und magsichen Welt Chinas (Wiesbaden: Marixverlag, 2004), 276.).] pattern in the center and with a pattern of swirls at the bottom. The same patterns are also used to decorate the robes of the second Bogdo Gegen, the backrest of the seat and the throne cushions. In comparison to figs. 10-12, the two lotus flowers which the second Bogdo Gegen holds in his hands are quite small and the leaves have the shape of tridents, in a way reminiscent of the European fleur-de-lys design. The throne stands on a rock plateau that is enclosed by water from both sides and covered with scattered tufts of grass. In the background blue and dark green mountain peaks and rounded-off Chinese-style mountains rise up into the sky. In the deep blue skies, the triad of Buddha Śākyamuni (in the middle), the Medicine Buddha (skt. Bhaiṣajya-Guru; tib. Sangs rgyas sman bla) (left side), and the Buddha of Limitless Light (skt. Amitābha; tib. 'Od dpag med) (right) appear amidst pink and blue mushroom-clouds. On the left and right side of the throne the White (skt. Sitā-Tārā; tib. sGrol dkar) and Green Tārā (skt. Śyāmā-Tārā; tib. sGrol ma) have manifested.

The exact outlines and the depth of the composition indicate that the composition dates at least to the beginning, if not to the end of the 20th century.

Conclusion

The above comparison of some portraits of the first and second rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtus (figs. 2-13) shows that there are different iconographic prototypes for their representation in Mongolian and Buryatian Buddhist art. As it is characteristic for traditional Tibetan and Mongolian art, the hand gestures, iconographic attributes and facial features correspond in most of the images discussed. However, the head gear, the surroundings and the accompanying figures exhibit differences.

Generally speaking, the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu (Zanabazar) can be identified by a bald head, receding black hair, a mustache which is sometimes implied by two or three black dots, long ears, and a youthful face. He holds a golden rdo rje in his right hand at the level of his heart and a silver bell in his left hand in his lap. The iconography follows the representation of Tāranātha (fig. 1). In some representations, the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukthu wears a black Mongolian-style hat (figs. 7, 8), while in others the head and body halo, usually used to symbolize the Buddha state of a high Buddhist master are missing (figs. 4, 9).

Analysis has shown that there are at least four different schemes of composition.

The first prototype depicts Zanabazar together with the fifteen previous incarnations of Tāranātha,which are arranged as side figures on the sides of the painting (figs. 4, 7). The line of incarnations can either start with the Buddha of Limitless Light Amitābha (tib. 'Od dpag med) (fig. 4) or Cakrasaṃvara and Vajravārāhī in union (figs. 7, 10), and close with Tāranātha (figs. 4, 4b) or another portrait of Zanabazar (figs. 7b, 10a). In this prototype, Zanabazar is represented with differing iconographic features. He wears a yellow paṇḍita hat and holds a vase with the nectar of long life and two lotus flowers on which a rdo rje and a bell lie in the gesture of meditation in his lap (figs. 7b, 10a).

The second prototype shows Zanabazar accompanied by two monks standing on the left and right side of his throne and carrying various offerings and ritual objects (fig. 5).

The third prototype follows the most simple compositional layout and is, therefore, most frequently used within Mongolian Buddhist painting (fig. 6). In this prototype, Zanabazar is shown alone sitting on a throne pedestal in the front; at either side two tables with offerings and ritual implements are arranged.

A fourth version depicts Zanabazar as an elderly person with short black hair and holding a Tibetan book with both hands in his lap (fig. 9). He is surrounded by several Buddha forms that are arranged at the top and the bottom of the painting.

The second rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu (Bogdo Gegen) is depicted with a yellow pointed paṇḍita hat (figs. 10-13). In his left hand, he holds a begging bowl in meditation gesture (skt. dhyanāmudrā; tib. nyam bzhag phyag rgya) in his lap. With his right hand, he performs the gesture of granting refuge (skt. śaraṇagamana-mudrā; tib. skyabs sbyin gyi phyag rgya) at his heart. Additionally, he holds two lotus flowers one topped by a rdo rje and the other by a bell. In most of the images he is portrayed with similar youthful facial features (figs. 10b, 11c, 12c). By contrast, he is depicted as an elderly person and with the physiognomic characteristics of the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu in fig. 13a.

Again, several compositional prototypes exist. Whereas in figs. 10-12 the same iconographic prototype has been used for the depiction of the second Bogdo Gegen, the details in the background differ. In fig. 10 the figures of Tāranātha's previous existences are shown in the background, whereas in figs. 11 and 12 scenes from his life and various Buddha forms are depicted.

In fig. 13 the landscape composition in the background and the side figures follow a completely different scheme that contrasts with figs. 10-12.

The paintings discussed show some corresponding stylistic features such as a uniformly deep-blue sky (figs. 5, 7, 9, 10-13)[54David Jackson notes that this special treatment of the sky is common for thang kas of the Sa skya Jo nang-school (Jackson, History of Tibetan Painting, 191).] with pastel-colored (fig. 13) and rainbow-hued (figs. 5, 7, 10) Chinese mushroom (chin. rúyì)-clouds (figs. 11-13), or the triangular hills in the background which are outlined by plants or fir-trees (figs. 4, 9, 10) and pinkish clouds (fig. 9). Besides these features, a similar pattern of golden swirls, circles, cross-shaped flowers and continuing twining vines[55In particular, plant volutes and patterns were employed in decorative motives in art of the Chinese Yuan period (1279-1368). These specific motives were derived from Central Asian art (Gisela Pause, “Die Ranke in der Chinesischen Kunst des 1. Jahrtausends n. Chr.” (PhD diss., University of Heidelberg, n.d.). ] is in evidence in the decoration of the figure's clothes, the throne drapery and other objects such as sun-discs the protective Buddha forms are standing on (figs. 6a, 7a, 9a, 10b, 11c, 12c, 13a). In some of the compositions even the Chinese shou character, meaning long life, can be found (figs. 5, 12). A further characteristic are the exuberant and colorful lotus or peony blossoms, growing on both sides of the throne or on a tree behind it (figs. 9, 10-12). In some of the paintings, the open flowers serve as a platform for the lotus throne of the side figures (figs. 10-12). Typical of the Mongolian thang kas discussed are the twofold lobed petals of the main figure's lotus throne, alternately colored blue and green (figs. 10, 11). In between them, the single stamen are sometimes emphasized by colorful dots (fig. 10).

Although the compositions appear flat, a certain degree of volume is achieved by a staggered arrangement of the background elements such as the hills and mountains (figs. 4, 7, 9, 10-13) or by features of the throne constructions (figs. 6, 7). In some of the paintings the throne seats and offering tables are painted as viewed from above (figs. 6, 7, 9, 10), or their sides are reduced in their perspective (figs. 4, 6, 13)[56Linda Komaroff mentions that space was redefined within the Mongol art of the Persian Ilkhanate during the 13th century. To create an effect of depth and space, a variety of techniques including the convergence or overlapping of diagonal lanes within the landscape were employed by the book illustrators of that time. Moreover, the landscape was laced with tufts of grass similar to the topping of the triangular hills in the landscape of Mongolian Buddhist thang kas. Similar techniques were applied for Chinese textiles (Komaroff, “Transmission and Dissemination of a New Visual Language,” 183.).].

The analysis of the above portraits shows that two different painting techniques are applied. A part of the paintings (figs. 6, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13) is carried out in tempera technique using a thick color application and bright contrasting colors (figs. 6, 12). Thereby, the shading is often elaborate and the outlines are painted in gold (fig. 12, 13). The preferred colors are red and blue (fig. 4-7, 9-11) and earthy ocher shades (figs. 12). In some of the paintings, a specific white-pink shade is used to accentuate the head halos (figs. 6, 11, 12), the lotus flowers (figs. 11, 12), the figures' skin (figs. 6, 12), and other objects such as the throne drapery or the surface of the side tables (fig. 6). In this category of paintings, the figures' faces and proportions are usually drawn quite imprecisely (figs. 6, 12), thus creating a bold and naïve impression. On the other hand, the freely applied cloth patterns and grass cover (figs. 12, 13) are very dynamic elements that may even evoke a modern and “abstract” connotation - to the Western viewer, at least.

The other parts of the paintings show a technique similar to water color painting[57Hummel assumes that this technique had its origin in China (Hummel, “Lamaistische Malereien,” 20).] (figs. 4, 11). The colors are blurred, leaving some parts of the canvas uncovered by paint. In addition, the outlines are applied in a graphical or sketchy manner (fig. 11).

Very specific details of the Mongolian compositions discussed are for example the panels (figs. 6, 7) and niche-like (fig. 9) throne constructions used for some of the portraits of the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu, or the small thang ka that is fixed on an honor parasol and depicts the first/fourth Panchen Lama (fig. 4a), the teacher of the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu. The protective Buddha forms are surrounded by orange, red, yellow or black flames (fig. 11, 12).

The Buddha forms that are depicted as side figures such as the Green and White Tārā (fig. 13), the protectors dGra lha (figs. 11, 12), Yama (figs. 11, 12), Yamāntaka (figs. 11, 12) and the six-armed black and white Mahākāla (fig. 9) are characteristic of Mongolian Buddhism. Some of the Buddha aspects such as Vajrasattva/Vajradhara (fig. 9) show a unique iconography and others such as Cakrasaṃvara and Vajravārāhī (figs. 7, 10), Sarasvatī (fig. 9), Mañjuśrī (figs. 9, 11, 12) and Avalokiteśvara (figs. 11, 12) directly hint to Tāranātha, Zanabazar or the biography of the second Bogdo Gegen.

In all portraits the first and second rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu are represented frontally, whereas the side figures are depicted in a semi-profile and aligned to the main figure (figs. 4, 7, 10). In general, the arrangement of figures corresponds to the traditional composition scheme of a Buddha, who is depicted frontally in the center of the composition, and two accompanying bodhisattvas, who are shown on a smaller scale and in a semi-profile standing on the left and right hand side (fig. 5).[58Seckel, “Die Darstellungs-Modi des En-Face, Halbprofils und Profils im Ostasiatischen Porträt”, 206-08.]

Both the first and the second rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu are characterized by stylized, youthful facial features (figs. 4a-7a, 9a). By comparison, the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu shows more individualized features such as the bald head, the mustache or the long, sticking out ears (figs. 2-9). This might be due to the fact that there existed/exist more and much elaborate prototypes or nga 'dra ma- or even nga 'dra ma phyag mdzad-portraits of the first rJe btsun dam pa Khutukhtu who had an exceptional position among the eight Bogdo Gegen incarnations.

Although physical resemblance was quite an important issue within Tibetan and Mongolian Buddhist lama portraiture, we should keep in mind that it was not the most important one. In Chinese art “individualization”[59In analyzing a Chinese ancestors' portrait of the Ming time (1368-1644) in which the family members of three generations are represented, Jorinde Ebert has very convincingly pointed out that the same stencil was used for all the figures' faces. Individualization was only achieved by small alterations of the lines defining the hair line, the nose and the shape of the eyes and mouth. Thus, the face of each person looks deceptively unique (Jorinde Ebert, “Drei Generationen auf einem chinesischen Ahnenporträt der Religionskundlichen Sammlung Marburg,” in Das Bildnis in der Kunst des Orients, ed. Martin Kraatz (Stuttgart: Steiner, 1990), 274-75.).] was mainly achieved by the setting, the objects and figures surrounding the person portrayed.