OFFICICAL PORTRAITS AND THEIR POLITICAL FUNCTIONS

SOOMI LEEThis essay starts from this possibility and argues that the management of official portraits—from portraits of kings to portraits of officials—including their production, distribution, and storage, served as a means of governance during the Joseon period, and that a political intention underlaid the state project of official portrait production.

ACHIEVING A LIFELIKE PORTRAIT

During the Joseon period, the production of portraits entailed a complicated process, with procedures even more rigorous for the portrait of a king.[2] Portraits of a king were treated with reverence and esteem because during this era a portrait was believed to contain the spirit of the sitter himself. Provisional directorates were established according to the type of portraits, and supervising officials, painters, and other artisans were selected and appointed to the relevant directorates.

In the case of kings’ portraits, when a draft portrait (or a preliminary sketch) was completed, high officials, officials of the directorate in charge, the crown prince, second- or higher-rank officials who had served at the Office of Royal Decrees (Hongmun’gwan), royal secretaries, official historians, and other related officials all reviewed the sketch to point out insufficiencies or flaws. The king himself also voiced opinions and ordered corrections. In order to make a draft as complete as possible when portraying a living king, drafts were repeatedly developed until a satisfactory result was achieved.[3] Once completed, the draft portrait was traced out on silk in ink, a process known as sangcho. After drawing the outlines, colors were added to the silk. The king frequently visited painters during this coloring process to offer them as many opportunities as needed to observe him directly. The king exchanged opinions with officials over points for improvement, and once the coloring was completed, the painting underwent a final examination by the king and his high officials.

Securing realism was among the most important tasks for portrait production. The production of a king’s portrait was subject to particular attention from the king and the royal court, and kings would take a keen interest in examining the results of the sketching and coloring processes. For example, in the process of creating a portrait of King Sukjong (1661–1720; reigned 1674–1720), if the king’s face was difficult to see with the portrait laid on the floor, a freshly produced portrait was ordered set upright for examination. Also, a paper was attached to the back of the portrait to allow closer observation of the color of the king’s face. The king even climbed up on a ladder to view his former portaits for comparison with the new version.

Despite such efforts, however, records show that it could be challenging to achieve a lifelike portrait. While participating as a civil official in the production of a portrait of King Sukjong in 1713, Kim Jingyu (1658–1716) argued that painters and officials should be provided additional chances to observe a king’s face closely.[4] According to Kim, while it was hard enough to accurately depict a scholar-official whom a painter could freely observe over extended periods, it was even more difficult to objectively portray a king when sufficient time for observation was not allowed. Probably in recognition of such difficulties, King Sukjong invested considerable effort to ensure that his image could be precisely captured in his 1713 portrait.

While great care went into achieving accurate portraits, there were many opportunities for subjectivity to influence the production and examination of such images. Portraiture is about creating a visual likeness of a real person. However, a painter can create wide variations in the image by changing the expression on the face, the color, or the posture of a figure. While reflecting the subject as closely as possible is considered a fundamental quality of portraiture, the opinions of the subject or of observers can intervene in portrait production. Those who review a portrait are influenced by their beliefs and academic background, as well as by the traditions and conventions with which they are familiar.

Joseon-dynasty official portraits of kings or officials commissioned by the state resulted from cooperation among court painters who all followed a series of procedures to meet the sanctioned requirements. Portrait production demanded agreement among the subject, commissioners, painters, and objective observers or reviewers not directly involved in the portrait production. During the process of pursuing consensus, the king could demonstrate his authority while exchanging opinions with his officials.

Portraits from the Joseon period depict their subjects either in official robes or in casual attire. It is recorded that kings were presented in diverse types of clothing and postures, but all the portraits surviving today show the kings in official dress. This is probably because the official dress was considered to most effectively demonstrate the ruler’s supreme power. In addition to kings’ portraits, all other extant official portraits show their figures in official attire, creating authoritative images of men with dignified postures and stern looks. These portraits were probably intended to show descendants and ordinary people exemplary officials who devoted their lives to the service of their country.

When a king’s portrait was finally complete, it was mounted on silk, inscribed with a title related to the name of the king, date of production, and other information, and was enshrined in a royal portrait hall, known as jinjeon, at an auspicious time on an auspicious date.

PORTRAITS OF KING TAEJO, FOUNDER OF THE JOSEON DYNASTY

Portraits of kings are among the most important visual symbols of a country.[5] In the Joseon dynasty, the portrait of King Taejo (1335–1408; reigned 1392–1398), also known by the name Yi Seonggye, possessed a particularly political nature as the official image of the founder of the new dynasty. Following the founding of the Joseon dynasty in 1392, this era saw the state ideology shift from Buddhism to neo-Confucianism. The new ruler eradicated the cultural legitimacy of the past dynasty, Goryeo (918–1392), and propagated the new cultural authority of the Joseon dynasty. Events such as the demolition of cultural symbols of the Goryeo dynasty and nationwide enshrinement of portraits of the founder of the Joseon dynasty were actually closely intertwined and aimed at creating a centralized state.[6]

An essential case study of this transformation is the establishment of the Royal Portrait Hall of King Taejo (Taejo Jinjeon), as professor and art historian Cho Insoo’s research details.[7] A Taejo Portrait Hall was a place to enshrine a portrait of King Taejo, the founder of the Joseon dynasty. The first Taejo Portrait Hall was the Junweon Hall built in Yeongheung, Hamgyeong province, the birthplace of Yi Seonggye, in the second month of 1398, the seventh year of his reign (fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Portrait of King Taejo at Junwon Hall in Yeongheung |

Portraits of the founder of the Joseon dynasty were enshrined in his hometown, in the capital cities of the former dynasties, including Unified Silla (668–935) and Goryeo (918–1392), as well as in the capital of the Joseon dynasty. After a portrait was enshrined in his ancestral seat, the last portrait of King Taejo was finally enshrined in Gaeseong (today in North Korea), the capital city of the Goryeo dynasty. In 1418, King Taejong (1367–1422; reigned 1400–1418), the son of King Taejo, launched the establishment of the Taejo Portrait Hall in Gaeseong, and his son, King Sejong (1397–1450; reigned 1418–1450), finished the work. The completion of all the Taejo Portrait Halls took place in 1419, during the first year of King Sejong’s reign. It is impressive to note that King Sejong completed constructing the Taejo Portrait Hall in Gaeseong a year after he became the king. Furthermore, the unique existence of detailed records of the ceremony of the enshrinement of the portrait in Gaeseong, in contrast to the complete lack of records about events related to the former enshrinements, indicates that enshrining the portrait of King Taejo in Gaeseong had a political motive.

After King Taejong had begun the enshrinement of a series of the founder’s portraits, and once King Sejong completed the project, King Sejong began disposal of the royal portraits and statues from the Goryeo dynasty. When Yi Seonggye (King Taejo) enthroned himself as the first king of Joseon in 1392, he moved the portraits of the kings of the Goryeo dynasty from Gaeseong to Majeon in Gyeonggi province. After this, the number of ceremonies for enshrining the Goryeo royal portraits was gradually reduced. In 1426, King Sejong eventually incinerated all the draft portraits of the kings and the queens of the Goryeo dynasty stored in the Bureau of Painting (Dohwawon). Although this act can be interpreted as being a conventional disposal of sacred objects, it was more of a symbolic severance of the legitimacy of the Goryeo dynasty. Then in 1427 and 1428, King Sejong ordered the burial of the portrait of King Taejo Wang Geon (877–943; reigned 918–943), the founder of the Goryeo dynasty, and portraits of the meritorious officials of the dynasty in proximity to the royal tomb. Finally, King Sejong finished this task with the 1430 burial of the eighteen portraits of the Goryeo kings in a sacred place.

Joseon rulers established portrait halls to house the portrait of King Taejo throughout the country and gradually eliminated the portraits of kings of the Goryeo dynasty, thereby erasing traces of the preceding dynasty. Portraits of kings represented absolute authority, and production or removal of such portraits was a highly political act associated with the legitimacy of the dynasty.

PORTRAITS OF KING'S SUBJECTS

During the Joseon period, kings ordered the production and preservation of portraits of their subjects in order to recognize their loyalty.[8] Portraits of meritorious subjects who rendered distinguished service to the king or the country are among such examples. Across the Joseon period, a total of twenty-eight titles for meritorious subjects were granted, and rewards were offered according to the grades of merit of these subjects. Portraits of meritorious subjects were commissioned by the state and were offered to the families of the relevant subjects. The last meritorious subject title, known in Korean as Bunmu gongsin, was granted in 1728, the fourth year of the reign of King Yeongjo (1694–1776; reigned 1724–1776), to reward officials who performed meritorious deeds in the suppression of the rebellion led by Yi Injwa (1695–1728).[9] After this occasion, no portrait of a meritorious subject was produced for the remainder of the Joseon period.

Fig. 2

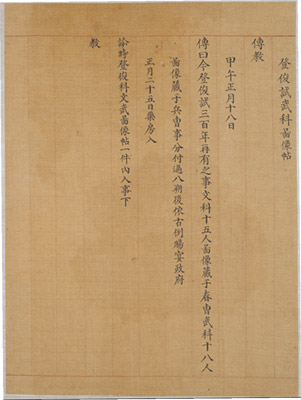

King Yeongjo's decree in the

Album of Portraits of Successful Applicants

in the Special Military Examination. The text in the Album of Portraits of Successful Applicants in the Special Military Examination (Deungjunsi mugwa dosangcheop) begins with King Yeongjo’s instructions on the production of this album (fig. 2). This commemorative album includes the portraits of eighteen officials who passed the special military examination for incumbent officials held in 1774, the fiftieth year of the reign of King Yeongjo (fig. 3). The king took a special interest in this album of portraits and ordered that a copy be preserved in the office of the Ministry of War within the royal palace. He thus regarded the successful applicants as equivalent to meritorious subjects and believed that they would faithfully guard the throne for himself and his grandson who later became King Jeongjo (1752–1800; reigned 1776–1800).[10] By producing the portraits of officials who passed the special examination and preserving them in the central government office, King Yeongjo might have intended to declare that he had established unprecedentedly close relationships with his subjects.

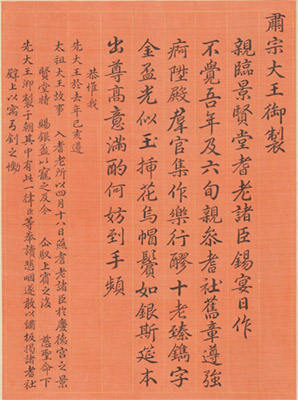

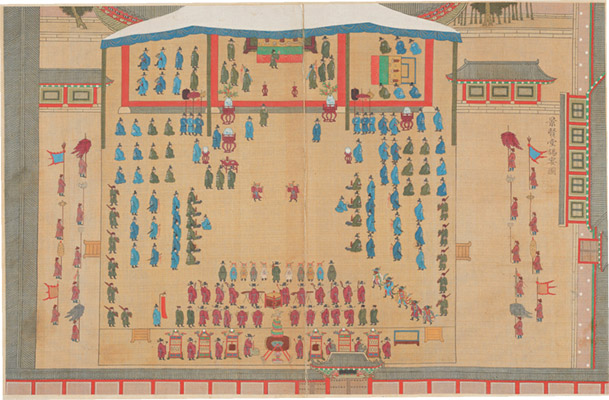

Portraits of officials who were admitted to the Bureau of Elderly Officials, called Giroso, provide another example of commemorative portraits kept in a central government office. In the Joseon period, civil officials aged seventy or over who had served in government posts of at least senior second rank were entitled to join the group of elderly officials and referred to as elderly officials (Girosin). The text in the Commemorative Album of King Sukjong’s Entry into the Bureau of Elderly Officials in the Gihae year (Gihae gisa gyecheop) was produced to celebrate King Sukjong’s entry into the Giroso upon the proposal of the members of the bureau, in 1719 when he was only fifty-nine years old.[11] This album includes a message from King Sukjong (fig. 4), a list of elderly officials of the Giroso, five paintings illustrating major events at the banquet (fig. 5), half-length portraits of the elderly officials (fig. 6), congratulatory poems by the members, and a list of officials and painters involved in the production of the album.

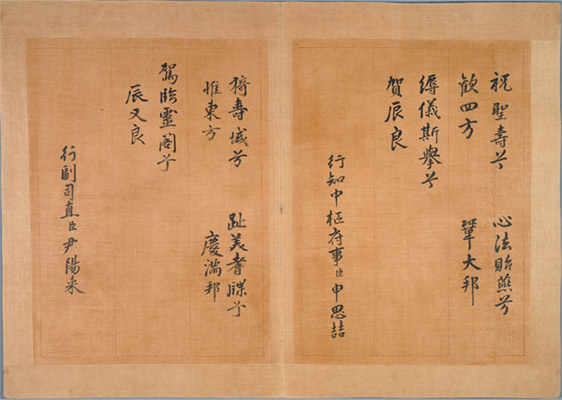

The king’s message and the banquet the album records are significant in several respects. First, by entering the Bureau of Elderly Officials at the age of fifty-nine, King Sukjong declared that he was following in the tradition of King Taejo, who is known to have joined the bureau at sixty.[12] Second, King Sukjong held a banquet to honor senior officials who closely assisted the king as his high officials and interacted with them. This album of paintings visually demonstrates the personal connection and loyalty between King Sukjong and his subjects. Succeeding in the tradition of King Sukjong, King Yeongjo produced the Commemorative Album of King Yeongjo’s Entry into the Bureau of Elderly Officials (Gisa gyeonghoecheop) in commemoration of his entry into the group in 1744.[13] This album includes writing by King Yeongjo, five paintings of the banquet, the individual portraits of eight elderly officials, and handwritten poems by the officials (fig. 7). This album shows how the king and his subjects cemented their relationship by exchanging poems at official banquets. During such events, the king offered poems or prose to share his vision with the officials, and the officials reciprocated with their own poetry. In this way, the king shared his cultural tastes and governing philosophy with his subjects, and the subjects gained a chance to evaluate each other’s skills in literature and calligraphy.

Fig. 3 Portrait of Yi Jang’o among the eighteen military officials in theAlbum of Portraits of Successful Applicants in the Special Military Examination. |

Fig. 4 King Sukjong’s pronouncement in the Commemorative Album of King Sukjong’s Entry into the Bureau of Elderly Officials in the Gihae year. |

Fig. 5 Banquet given by King Sukjong in Gyeonghyeon Hall in the Commemorative Album of King Sukjong’s Entry into the Bureau of Elderly Officials in the Gihae year. |

Fig. 6 Portrait of two elderly officials—Gang Hyeon (right) and Hong Manjo (left)— in the Commemorative Album of King Yeongjo’s Entry into the Bureau of Elderly Officials. |

Albums of portraits served to inform posterity that the descendants’ ancestors had attended such honored events with kings. During the late Joseon period, producing an album of portraits of officials was a cultural and philosophical means to maintain an ideal relationship between the ruler and his subjects based on a shared vision and mutual loyalty. A series of processes including producing, enshrining, and distributing portraits helped to elevate royal authority and enhance the bond between the king and his subjects. It also allowed the king to exercise emotional and personal connection with his subjects while emphasizing the legitimacy of his reign in a most cultured way.

Fig. 7 Poems of two elderly officials—Sin Sajeong (right) and Yun Yangrae (left)— in the Commemorative Album of King Yeongjo’s Entry into the Bureau of Elderly Officials. |

Footnotes:

1. For an overview of Korean portraiture, see National Museum of Korea, The Secret of the Joseon Portraits (Seoul: National Museum of Korea, 2012).

2. Cho Sun-mie, Hanguk-ui chosanghwa: hyeong-gwa yeong- ui yesul [Portraits of Korea: Art of shape and spirit] (Paju: Dolbegae Publishers, 2009); Yi Songmi, Yu Songok, and Kang Sinhang, Joseon sidae eojin gwangye dogam uigwe yeongu [A study of the archival record related to royal portraits in the Joseon dynasty] (Seongnam, Korea: Academy of Korean Studies, 1997); Yi Song-mi, “The Making of Royal Portraits during the Choson Dynasty: What the Uigwe Books Reveal,” in Bridges to Heaven: Essays on East Asian Art in Honor of Professor Wen C. Fong, vol. I (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012): 363–386.

3. Lee Soomi, “Two Stages in the Production Process of Late Joseon Portraits: Sketches and Reverse Coloring,” Journal of Korean Art and Archaeology 5 (2011): 39–57.

4. Kim Jiyoung, “Joseon hugi yeongjeong mosa-wa jinjun unyeong-ae daehan gochal” [Production of royal portraits and operation of royal portrait halls in the late Joseon dynasty] in Kyujanggak sojang uigwe haejejip [Annotation of the royal protocol in the collection of the Kyujanggak Library] (Seoul: Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies, 2005), 201–202; Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies, Kyujanggak sojang bunryubyeol uigwe haeseoljip [Annotated classification of the royal protocol in the collection of the Kyujanggak Library] (Seoul: Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies, 2005), 202–205.

5. For an overview of Joseon royal portraits, see Cho Insoo, “Royal Portraits in the Late Joseon Period,” Journal of Korean Art and Archaeology 5 (2011): 8–23.

6. Lee Soomi, “Building Cultural Authority in Early Joseon Korea (1400–1450),” in Ming China: Courts and Contacts 1400–1450, The British Museum Research Publication 205 (London: The British Museum, 2016), 211–218.

7. Cho Insoo, “Sejongdae-ui eojin- gwa jinjeon” [Royal portraits and portrait halls in the Sejong period] in Misulsa-ui jeongrip- gwa hwaksan [Structure and diffusion of art history], vol. 1 (Seoul: Sahoe pyeongron, 2006): 160–179.

8. For an overview of Joseon- dynasty portraits of meritorious officials, see Kang Kwanshik, “Literati Portraiture of the Joseon Dynasty,” Journal of Korean Art and Archaeology 5 (2011): 25–29.

9. Cho Sun-mie, “Joseon Dynasty Portrait of Meritorious Subjects: Styles and Social Function,” Korea Journal 45, no. 2 (2017): 151–181.

10. Chang Jina, “Portrait Album of Successful Candidates from the Military Division of the Special State Examination and Its Characteristics as a Collection of Portraits of Meritorious Subjects,” Journal of Korean Art and Archaeology 11 (2017): 106–121.

11. For the Commemorative Album of King Sukjong’s Entry into the Bureau of Elderly Officials in the Gihae year, see Gisa gyecheop [Special exhibition of the Commemorative Album of King Sukjong’s Entry into the Bureau of Elderly Officials], cat. 5 (Seoul: Ewha Womans University, 1976), 47–77; Joseonsidae chosanghwa [Portraits of the Joseon dynasty], vol. 3 (Seoul: National Museum of Korea, 2009), 10–25.

12. King Sukjong joined the Bureau of Elderly Officials (Giroso) at the age of fifty-nine following the example of King Taejo, the founder of Joseon. While the general rule for entering the bureau was to be seventy years of age, kings could enter at a younger age.

13. For the Commemorative Album of King Yeongjo’s Entry into the Bureau of Elderly Officials, see Joseonsidae chosanghwa [Portraits of the Joseon dynasty], vol. 3 (Seoul: National Museum of Korea, 2009), 10–25.

The catalogue of the exhibition can be ordered at https://amzn.to/3lPlNdB

Sketching Legacy: Korean Portraiture at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco by Hyonjeong Kim Han

Bunmu gongsin, the Last Meritorious Officials of the Joseon Dynasty by Kyungku Lee

Beyond Portraiture: New Approaches to Identity in Contemporary Korean and American Art by Robyn Asleson

Back to main exhibition | Installation images | Introduction

asianart.com | exhibitions