BEYOND PORTRAITURE: New Approaches to Identity in Contemporary Art

ROBYN ASLESONYUN SUKNAM: ENVISIONING WOMEN'S LOST HISTORIES

Yun Suknam’s pioneering depictions of women began as a quest to recover her sense of personal identity, which had been erased by a decade of traditional domesticity. In 1979, at the age of forty, she revived her childhood ambition of becoming an artist, later recalling, “I could not continue suppressing questions about my self-identity I thought that creating art was a way to look for my real self.”[1] After studying traditional calligraphy and developing a painting practice in Korea, Yun made two transformative visits to New York City in 1983–1984 and 1990–1991 that introduced her to the dramatic possibilities of installation art.[2] On her return home, she broke free from the flat surfaces of traditional Korean portraiture and began to produce wood assemblage pieces focused on feminist themes—a subject all but unknown in Korea at the time.[3]

Fig. 1: MOTHER III-LADY, 1993

by Yun Suknam (b. 1939)

Acrylic on wood

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. Yun began her quest for self-understanding by probing her mother’s history. Over time, her work took on broader theoretical and societal implications for Korean women generally. Her groundbreaking 1993 solo exhibition, Eyes of the Mother, featured six wood assemblage portraits that traced her mother’s life from youth to old age. The series conveys respect for the courage and resilience of women like her mother while deploring the heavy personal toll exacted by the Confucian ideal of maternal self-sacrifice.[4] The first work in the series, Mother I—19 Years Old, depicts a carefree teenager whose skirt floats jauntily in the breeze. Her buoyant energy dissipates as the series continues. The rigidly upright figure in Mother III—Lady is far more somber (fig. 1). Dressed in traditional hanbok with her hands folded passively in her lap, she is confined within a rectangular frame that suggests the constraints imposed on her, while her confrontational stare—a rarity in Korean female portraiture—hints at formidable inner strength. The series closes with Yun’s vision of the long-term consequences of enforced domesticity and self-sacrifice, with her mother reduced to a shrunken, hunched-over figure, neglected and forgotten by society. While charting her mother’s changed appearance over time, Yun is less interested in documenting her exact likeness than in conveying a sense of her psychic and physical decline.

Yun’s refusal to comply with the artistic convention of mystifying and idealizing women extended to the materials she used for her early assemblage portraits. She composed them of repurposed scraps of wood scavenged from the street, including the chair fragments that appear in Mother III. In the aged wood, weathered by time and use, she saw evidence of a life history that reminded her of the soft, wrinkled, careworn skin of an aging woman’s face.[5]

In 1995 Yun embarked on a series of multimedia installations that served as conceptual self-portraits intended to embody the mental distress she experienced as a middle-class housewife. Her Pink Room installations exaggerate stereotypically feminine decor to the point of delirium (fig. 2). Elaborately carved sofas and chairs stand on legs fashioned from curved knives and often show metal spikes protruding from the hot-pink satin upholstery. Vividly patterned pink walls create a disorienting, hallucinogenic effect, and pink beads scattered across the floor indicate the impossibility of finding a secure footing.

Fig. 2: PINK ROOM V, 1996–2018, by Yun Suknam (b. 1939) Mixed media. National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. |

In addition to representing the lives of contemporary Korean women, Yun has probed the histories of notable women from the Joseon dynasty. A strong sense of personal identification—a feeling that “these women dwell in my body and soul”—has fueled her desire to “unearth their sorrow, agony, and anger out of the dark grave of history and give them shape.”[6] Among her subjects are Heo Nanseolheon (1563–1589), a highly gifted and well-educated poet, who wrote movingly of the loneliness endured by women in unhappy marriages such as hers, before dying at the early age of twenty-six (cat. 7). To express her sympathetic connection with Heo Nanseolheon, Yun created an imaginative double portrait in which a modern woman with bobbed hair and a pendant earring extends an impossibly elongated arm across space and time toward the seated poet, while at the same time unfurling a scroll that bears the calligraphed marks of her poetry. “We don’t know much about the women who lived four hundred years ago,” Yun has observed. “The extended body parts are an expression of my wish to reach out. It is a craving for communication with other women.”[7]

YOUNG JUNE LEW: TRANSCENDENT IMPRESSIONS OF EVERYDAY LIVES

Although she has worked in a figural mode for much of her career, Young June Lew is more interested in the soul than the body. A recurring theme of her art is the spiritual component within human beings that allows us to transcend our physical shells. After completing an undergraduate art program at the Ehwa Women’s University in Seoul, Lew moved to Los Angeles in 1973 and enrolled in the MFA program at California State University. Although she never adjusted to Southern California’s dazzling sunlight and lack of seasons, Lew enthusiastically embraced the unaccustomed approach to painting that she encountered there, which was less focused on developing technical expertise (as in Korea) than on engendering a process of self-discovery. “Gaining exposure to a different environment and culture was one way of discovering myself,” Lew has observed. “If I had stayed in Korea, I am sure I would have been a different artist by now.”[8]

Fig. 3: CYCLE OF TIME, 1997

by Young June Lew (b. 1947).

Mixed media on canvas In the early years of her career, Lew struggled with a conflicted sense of identity, torn between her dedication to painting and the deeply engrained traditional belief that a wife and mother should put her family’s interests before her own.[9] Lew credits her mother with instilling the courage to persist, even taking on Lew’s domestic responsibilities for a month while she made a life-changing trip to study art in Europe.[10] Her mother’s death in 1994 brought with it a profound sense of loss as well as a heightened awareness of the enduring impact our lives can have on others.

It also prompted a turning point in Lew’s work, leading her away from abstraction toward a more representational style. Inspired by the uncanny sense of her mother’s lingering presence in the familiar dresses she had worn, Lew embarked on a series of monumental canvases in which floating garments, empty of the bodies they once contained, nevertheless convey a palpable sense of human presence.

Like Yun Suknam, Lew gradually expanded her focus beyond the personal inspiration of her mother to a more universal human context. Works such as Cycle of Time feature generalized coat forms that are non-specific in terms of gender, age, and era (fig. 3). To create a distressed, time-worn appearance, Lew adopted the unconventional technique of painting the coats with black coffee. “I wanted to capture the stains, perspiration, wear and tear that clothing has when it’s really been lived in,” she has said.[11]

She conceives of these battered coats as immigrant figures— symbols of the human journey. “The everyday clothes we wear throughout our lives...contain so much of life and history in it,” she observes. As a result, “Clothing represents the journey of life to me.”[12]

Lew set her figureless garments against dark, densely textured backgrounds. In certain sections of her paintings, heavily worked, rugged surfaces suddenly clear to reveal an underlying pattern, such as the checkerboard in Cycle of Time. These vestigial signs of an early phase of the painting’s production carry associations with time and memory, which Lew often underscores through orderly sequences of numbers parsed out rhythmically across the canvas. The brilliant white slashes of paint in Cycle of Time have a startling immediacy, suggesting a flash of memory or a sudden epiphany.

Fig. 4: ORDINARY SAINTS, 2011. by Young June Lew (b. 1947). Mixed media on canvas |

Over the past several years, Lew has transitioned from figureless garments to paintings that focus on the human face. The change was inspired by her sense of the “sublimity in the faces of everyday people” and her desire to forge links between the past and present. The paintings in her series “Ordinary Saints,” begun in 2011, feature vaguely medieval but essentially symbolic faces in which we are all invited to see ourselves reflected (fig. 4). Often represented in group portraits or multipartite units, the figures express the unifying quality of the human condition and the artist’s sense of inner goodness radiating from each face. By erasing signs of individuality, she emphasizes a deep spirituality that surpasses difference and unites all people as partaking in the sanctity of life.

DO HO SUH: CONTEXTUALIZING THE SELF

Do Ho Suh has channeled his experience of cultural and geographic dislocation into sculptures and installation pieces that challenge the supposed oppositional relationship between the self and others. His work is often interpreted as a negotiation of the tension between the hierarchical collectivism of his youth in Korea and the individual egalitarianism he experienced in the United States.[14] But though grounded in personal experience, Suh’s art aspires to a universal significance beyond individual identity.

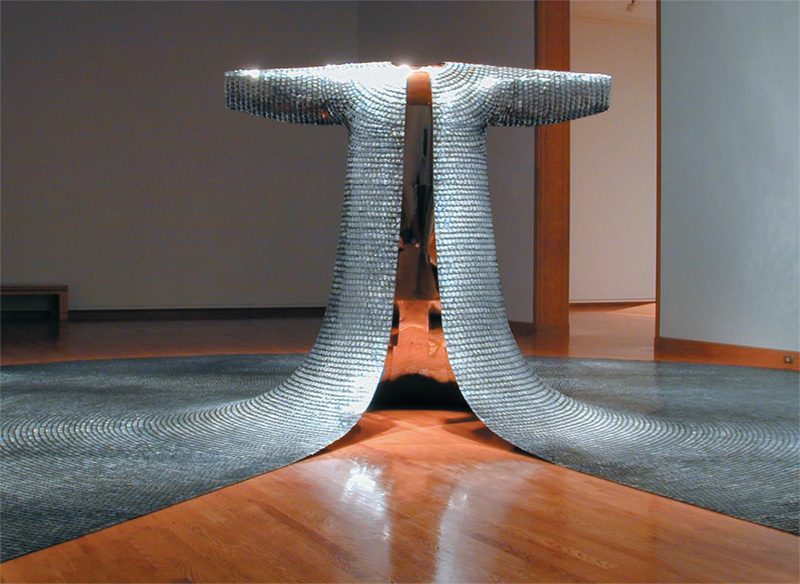

Fig. 5: SOME/ONE, 2001, by Do Ho Suh (b. 1962). Stainless steel military dogtags, nickel-plated copper sheets, steel structure, glass fiber reinforced resin, rubber sheets. Seattle Art Museum, gift of Barney A. Ebsworth, 2002.43. © Do Ho Suh. |

After receiving BFA and MFA degrees in traditional ink painting in his native Korea, Suh relocated to the United States to begin his formal education all over again, earning a second BFA at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1994 and an MFA in sculpture at Yale in 1997. An undergraduate class assignment first sparked Suh’s interest in probing the relationship of collectivism and individuality. Tasked with using a form of clothing to explore the issue of identity, Suh drew inspiration from his service in the Korean military, which he recalled as “a process of dehumanization” intended to undermine his individual identity while fostering collective identification with his comrades.[15] Playing off the use of military dog tags to document identity, he glued three thousand of them to a US Army jacket liner, creating a work, titled Metal Jacket (1992), that resembles a piece of ancient Asian armor. Elaborating on the concept a decade later in Some/One (fig. 5), Suh created a seamless fabric of conjoined dog tags that sweeps up from the floor to form what appears to be a larger-than-life, flowing suit of armor or an emperor’s shimmering robe. Circling around the sculpture from back to front, the viewer discovers that the resplendent colossus is actually an empty shell with a mirrored interior that reflects the viewer’s own likeness.[16] By means of this reflection, Suh invites the viewer’s personal identification with this formidable monument to subsumed individuality, but he imposes no moral judgment, leaving the interpretation of meaning to each viewer.[17]

Tension between individual and collective identity recurs in other examples from Suh’s early career, often treated as a deliberately unresolved question. In High School Uni-Face: Boy and High School Uni-Face: Girl (cat. 9), he created composite portraits from photographs of his high school classmates. At first glance, each portrait appears to represent a single face but is in fact a collective that dissolves difference and creates an image of homogeneous anonymity. Suh hints at the unmoored sense of self that can result from collective identity in Who Am We? (Multi) (2000) (cat. 9, fig. 2), a large sheet of wallpaper printed with tens of thousands of tiny yearbook photographs from his high school, spanning the years 1936 to 1983.[18] From a distance, the viewer perceives only a hazy pattern, but at close range individuals separate from the mass and become visible.

Suh has invoked his high school years in other works that explore the theme of individuality subsumed within a conforming collective. In High School Uni-Form (1997), three hundred identical suits are stitched together and attached to a rolling steel frame so that the closely bonded, interdependent mass can be moved in unison. A related work, Uni-Form/s: Self Portrait/s: My 39 Years (cat. 9, fig. 1), traces the artist’s progression from youth to manhood through the uniforms he wore during consecutive stages of school and military service. Suh’s sequential display of uniforms charts the passage of time and, along with it, a succession of socially mandated roles, from student to soldier. The empty uniforms resemble Young June Lew’s body-less dresses and recall her comment that “clothing represents the journey of life.” Suh’s visualization of his life as a series of socially predetermined roles also recalls Yun Suknam’s representation of the culturally mandated stages of a person’s life.

The family, like the military and the school, is a collective group that both empowers and constrains the individual.[19] Suh has examined this duality in a series of works that began with Paratrooper-I (2001–2003), in which the small figure of a soldier is connected by threads to an enormous parachute embroidered with the names of Suh’s family and friends—and their family and friends—to represent the “web of relationships” that shapes each individual.[20] Here again, Suh deliberately cultivated a sense of ambiguity as to whether the paratrooper is supported by this densely interconnected network, or rather, is struggling to escape from it.[21] In creating portraits of abstract community rather than precise individuality, Suh upends many conventions of traditional Korean portraiture.

AHREE LEE: THE PARADOXES OF SIMILIARITY AND DIFFERENCE

Traditional Korean culture and the immigrant experience have proven to be rich resources for Ahree Lee’s exploration of individual and collective identity. Born in Seoul, Lee was still a child when her family moved to Philadelphia, where she says she was “raised distinctively American.”[22] Drawing on her interdisciplinary academic training at Yale, where she received a BA in English literature and an MFA in graphic design, Lee explores issues of similarity, difference, and connection through multimedia works that encompass video, photography, and interactive installations.

Fig. 6: RIGHT/LEFT, 2014, by Ahree Lee (b. 1971). Still image from digital video. |

Resemblance and difference are central themes of Right/Left (fig. 6), a video diptych showing two similar but not identical faces on a split screen. The faces subtly evolve during the video’s two-and-a-half-minute runtime before merging at the end to reveal that they are opposite sides of the same woman’s face, each half having been mirrored to create a whole. The piece speaks to the bifurcation of identity, perhaps referring to the artist’s dual Korean and American heritage, but equally suggestive of the contradictory elements contained within and unified by the self. Lee calls attention to the hybrid nature of identity, which is often described as the merging of dualities: good and bad; yin and yang; public and private.

A further duality of Lee’s work is her use of state-of-the-art technology to explore ideas inspired by traditional Korean culture. For example, her 2015 video Bojagi (Memories to Light) takes its title from the traditional Korean wrapping cloth that women made by sewing together scraps of leftover fabric. Lee emulated the patchwork structure of bojagi in her video, which comprises excerpts from the home movies of Asian American families enjoying typical American activities—such as splashing in a backyard swimming pool, visiting a theme park, or going on a picnic. Although memories of activities such as these are intrinsic to Lee’s sense of personal history, she was accustomed to television, film, and advertisements portraying them exclusively in terms of Caucasian families.[23] Through Bojagi, she reclaimed and validated these experiences for Asian American families like her own, creating a sense of community and shared identity, and transforming the mundane snippets of everyday life into a mesmerizing kaleidoscope of nostalgic memories.

Fig. 7: PERMUTATION, 2015, by Ahree Lee (b. 1971). Software-generated video. |

Lee generates a more expansive sense of community in Permutation, a video installation in which thin, vertical sections of five or six portrait photographs roll across the screen to create a constantly changing composite image (fig. 7). Although the fragmentary facial features indicate different genders, ethnicities, and ages, the fluidly merging and mingling images emphasize commonality and create a holistic impression. Lee likens the photographic slices to “snippets of genetic code,” and interprets the video as an exploration of individual difference as well as collective identity.[24] The fluctuating composition of fragmentary photographs resembles the unique combination of DNA that differentiates each unique human from all others. At the same time, Lee notes, the photographic slices call to mind “the thousands of snippets of DNA that each person has in common with people around the world.”[25]

CONTINUITY WITHIN CHANGE

Present-day artists are separated from their Joseon-dynasty predecessors by myriad modern influences. The impact of Western contemporary art, egalitarian social movements (particularly feminism), geographic mobility, and digital technology have all contributed to a range of new approaches to the representation of the self. Yet within these divergent modes, common threads may be discerned in a number of sustained themes, including Confucian cultural values, the honoring of ancestry (both of family and of gender), the commemoration of significant events, and the productive pairing of innovation with tradition. Most significantly, contemporary artists resemble those of the Joseon dynasty in their recognition of the central paradox of identity: that collective contexts are instrumental in shaping the uniqueness of each individual.

Footnotes:

1. Na Young Lee, “Art Essay: Yun Suknam,” Feminist Studies 2, no. 2 (Summer 2006): 361–362.

2. “Lee Ihnbum Interviews Yun Suk Nam” (September 17, 2014), http://www.cultconv.com/English/Conversations/Yun_Suk_Nam/HTML5/testimonybrowser.html.

3. Whui-Yeon Jin, “Post-Colonialism and Suk-Nam Yun’s Images of Women: Mother Series and the Feminine,” Acta Koreana 6, no. 2 (July 2003): 1–2, 12; Hwa Young Choi Caruso, “Art as a Political Act: Expression of Cultural Identity, Self-Identity, and Gender by Suk Nam Yun and Yong Soon Min,” The Journal of Aesthetic Education 39, no. 3 (Autumn 2005): 79.

4. Caruso, 73, 77–78.

5. Kim Hye-Soon, “Gushing Tears from Wistful Totems,” trans. Kyung-Hee Lee. In Pink Room, Blue Face—Yun Suknam, edited by Beck Jee-sook (Seoul: Hyunsil Cultural Studies, 2009), 52.

6. Lee, 352.

7. Kim Hye-Soon, 70.

8. Etelka Lehoczky, “Artful Objects,” Chicago Tribune (April 10, 2002), 3.

9. Clarissa J. Ceglio, “Young June Lew: A Personal Journey to Universal Art,” Korean Culture (Summer 1999), 24, 26.

10. Lehoczky, 3.

11. Ceglio, 28.

12. Lehoczky, 3.

13. Richard Park, “Andrew Bae Interview,” Asian American Art Oral History Project 67 (July 4, 2013), 6, https://via.library.depaul.edu/oral_his_series/67.

14. Nan Jie Yun, “A Conversation with Do-Ho Suh,” in Do-Ho Suh (Seoul: Artsonje Center, 2003), 102–103.

15. “Some/One” and the Korean Military: Do Ho Suh,” art21 (orig. pub. September 2003; repub. November 2011), https://art21.org/ read/do-ho-suh-some-one-and-the-korean-military.

16. Audrey Walen, “Do-Ho Suh: Whitney Museum at Philip Morris,” Sculpture 20, no. 8 (October 2001): 72–73.

17. Lisa G. Corrin and Miwon Kwon, Do-Ho Suh (London: Serpentine Gallery and Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 2002): 13.

18. Regina Hackett, “Do-Ho Suh Makes Memory Tangible with Wallpaper, Floating Houses and Dog Tags,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer (August 9, 2002), https://www.seattlepi.com/ae/article/Do-Ho-Suh-makes-memory-tangible-with-wallpaper-1093239.php.

19. Sandra Wagner, “Personal Histories: A Conversation ith Do Ho Suh,” Sculpture 31, no. 9 (November 2012): 27–28.

20. Esther Eunsil Kho, “Korean Border-Crossing Artists in the New York Artworld: An Examination of the Artistic, Personal and Social Identities of Do-Ho Suh, Kimsooja, and Ik-Joong Kang,” PhD diss. (Florida State University, 2006), 97.

21. Tom Csaszar, “Social Structures and Shared Autobiographies: A Conversation with Do-Ho Suh,” Sculpture 24, no. 10 (December 2005): 34–35.

22. “Artist Statement,” Ahree Lee website (2015), https://www.ahreelee.com/work/permutation.

23. Meher McArthur, “We Are More Similar Than We Realize: Interconnecting Identities in the Work of Ahree Lee,” KCET Artbound (April 4, 2017), https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/korean-american-artist-ahree-lee-bojagi-multi-media-work.

24. “Permutation,” Ahree Lee website.

25. Ibid.

The catalogue of the exhibition can be ordered at https://amzn.to/3lPlNdB

Sketching Legacy: Korean Portraiture at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco by Hyonjeong Kim Han

Official Portraits and Their Political Functions by Soomi Lee

Bunmu gongsin, the Last Meritorious Officials of the Joseon Dynasty by Kyungku Lee

Back to main exhibition | Installation images | Introduction

asianart.com | exhibitions