Recently, The New York Times observed, “Everyone is going to Bhutan.” There are many reasons why, as we now can keenly see in this first-ever offering from the Land of the Thunder Dragon. Never colonized, by East or West, Bhutan has kept its identity intact, since unification three centuries ago. Bhutan is also the youngest democracy in the world, having on March 4, 2008 held a peaceful national election in transition from monarchism. Many challenges face her (and us). So we look to The Dragon’s Gift as coming from the land of Gross National Happiness (GNH) at a pivotal moment.

|

|

At the opening in San Francisco, the Honorable Lhatu Wangchuk, Ambassador to the UN, kindly advised me not to term Dragon’s Gift an exhibition. Rather, he said, “it is a special opportunity for those who visit to receive blessings from these special objects.” These hundred pieces, from the 7th to 12th century, are wonderful works of art, but were intended primarily not to please the eye alone, but as sacred objects of devotion, blessed by monks every day since being gathered together as collection (the monks tour with the show). Never available to tourists, 99% are from temples (from fieldwork at 200 sites); most are not even normally seen by Bhutanese citizens, shown only on certain days. Given how easily yak butter smoke can darken a thangka, it’s amazing how pristine everything on view has been preserved and/or restored; apparently the curators have given well, as well as received.

This nonpareil exhibition of tantra art, a decade in the making, has been highly anticipated for some time. On hand at the opening in San Francisco was the museum’s curator of Himalayan art, Therese Tse Bartholomew, who’d acted as Guest Curator, and Stephen Little, Director of the Honolulu Academy of Arts, originator of this ambitious undertaking. The product of an an army of scholars, officials, monks, cultural experts, and donors, it has been at the Rubin Museum of Art in New York City, and from San Francisco, it will travel to Musée Guimet in Paris, then the Museum of East Asian Art, Cologne.

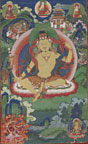

Fig. 1

Green Tara

|

|

One way to quickly distinguish Bhutanese sculpture from Tibetan is by noting the distinct crenellation of the leaf-form petals of the lotus thrones of deities (Fig 1, left). A distinguishing trait of Bhutanese thangkas is the inclusion of a rectangle on the mounting, below the image, as a kind of window inviting the eye in (althought this is also found in thangkas from “Greater Tibet”). Artisans would select the finest textiles, (even a Ming dragon), to increase merit. But these are mere details, up to an individual artist. Self-expression or imagination are not the goals here. Representation of each image follows strict tradition.

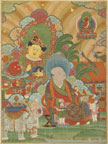

The earliest piece on view depicts goddess Kongtsedemo (Fig. 2, below), bare-bosomed but modestly skirted, blue-haired (signifying a peaceful attitude) and gold-faced (the gold being applied annually). Another local deity is Dorje Yudrönma (Fig. 3, below): in one hand she holds a symbol unique to Bhutanese tantric art, a crystal drum, as seen in both the adroit rendering in her thangka, and in her sculpture with actual glass.

Fig. 2

Kongtsedemo

|

Fig. 3

Dorje Yudronma

|

Fig. 4

Guru Nyima Ozer

|

Fig. 5

Padmasambhava

|

| |

Fig. 6

Guru Rinpoche

|

These native goddesses were pledged to protect the Dharma by Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche) who brought the Way of the Buddha to Bhutan after he came from Pakistan and converted Tibet. He looms large throughout, and is easily recognized by his hat with upturned lappets, fur boots, nice collar, feather in hat, and special scarf (Fig. 6, right). A very striking and compelling image of him is in his manifestation as Guru Nyima Özer (Guru Sunbeam, so called because of the legend that he could cause the very sun to remain still), seen here playing with sunbeams with his one hand (Fig. 4, above). Of the scenes of his life, in the background, over his right shoulder we see him using a mandala as a tool to teach. Elsewhere, as Pejung Dorje Guru, he crushes two figures who represent impediments to practice, and below them are slain soldiers on a battlefield (Fig. 5, above).

The thangkas can be hard to date, but each is a gem entire. Students of Vajrayana (the path of esoteric Buddhism centered in the Himalayas) can have a field day with the Complete Mandala, containing 32 individual mandalas within one thangka. Indeed, the exhibition is itself a complete mandala. A thangka of the historical Buddha is flanked by a suite of ten depicting the sixteen arhats, or perfected ones,, all eleven scrolls interlaced at the top (unique to the San Francisco showing) (Fig. 7, below). Here too is the traditional rigsum gönpo trinity of primary deities who protect the Dharma (“protectors”): Avalokitsehvara, embodiment of the compassion of all the Buddhas; Manjushri, embodiment of the wisdom of all the Buddhas (Fig. 8, below) ; and Vajrapani, the action or power of the Buddhas, from whose thunderbolt (vajra) to subdue demons we get the word Vajrayana (in a sculpture in Fig. 9, below). There are thangkas for guru yoga and for particular meditations, portraits of mahasiddhis (supreme adepts with magical powers) and figures of lineage (teachers of, say, the teacher of one’s teacher’s teacher) as well as local saints, such as divine madman Drukpa Kunley (shown in a sculpture in Fig. 10, below). Considering each piece shown as a spiritual map, this exhibition is an atlas, showing how tantra art can reveal all ten directions in time and space within and without.

Fig. 7

Monk Hvashang

|

Fig. 8

White Manjushri

|

Fig. 9

Vajrapani

|

Fig. 10

Drukpa Kunley

|

Along with being a stunning, elevating experience, Dragon’s Gift truly conveys Buddhist art as a skillful means (upaya) to sober the mind and open the heart, to elevate the spirit and instill the divine. In addition to the monks in residence performing daily puja and purification, and constructing a sand mandala (diagram of spiritual space and human consciousness), a key performative element here (and a curatorial coup) is Dragon’s presentation of sacred dance (Cham.). Now we can immediately make the vital link from images beheld in sculpture and thangkas, to their living embodiment in devotional, sacred ritual practice. Working with the Honolulu Academy, the Core of Culture Conservation Preservation spent over two years documenting and preserving Bhutanese dance, much of it endangered. (Whereas Bhutan had no tv up until 1999, Desperate Housewives is now a national hit.) For those unable to visit a museum and appreciate the juxtaposition of high-definition flat-panel video screens on walls alongside static objects, a DVD accompanies the superb catalog, with highlights from 300 hours of footage.

Fig. 11

Cham ritual dance

|

Fig. 12

Cham ritual dance

|

For the average Westerner, the word dance conjures up the idea of entertainment, something seen in a theater. Here, the world becomes a theater of the divine. In Buddhism as/in Perfomance (DK Printworld, New Delhi), David E.R. George writes: “Chams is arguably the climax of:

- the basic pattern of the Vajrayana whereby all abstractions are progressively symbolized and systematically personified — as means to enlightenment, as upaya;

- the basic practices of Vajrayana yoga — as a path of dramatic visualization and empathetic identification;

- the overall ethical requirement to enlighten, teach; and the fundamental commitment of the Vajrayana to a polarity of Philosophy and Performance, Precept and Practice, Wisdom and Action.”

This art not only draws us closer to the particular essences which the deities embody, but makes them eventually a part of us, for the benefit of everyone. Through movement and dance we can perceive the expression of the living word (the Dharma); a continuity, making the old new again, on a path of devotional spiritual transformation, body-spirit-mind as one. With such precious gifts as these in our midst, we might well consider Bhutan as well worth paying close attention to, especially now in these times of tremendous change.

Further schedule:

Musée Guimet, Paris, France: 6 October 2009 - 25 January 2010

Museum of East Asian Art, Cologne, Germany: 19 February - 23 May 2010

Museum Rietberg Zürich, Switzerland: 4 July - 17 October 2010

For Further Reading

The Dragon’s Gift: The Sacred Art of Bhutan, edited by Terese Tse Bartholomew and John Johnston

Bhutan: Land of the Thunder Dragon by John Berthold

Under the Holy Lake: A Memoir of Eastern Bhutan by Ken Haigh

A Painter's Year in the Forests of Bhutan by A. K. Hellum

Gross National Happiness of Bhutan by Anne Muller and Tashi Wangchukåç

Beyond the Sky and the Earth: A Journey into Bhutan by Jamie Zeppa

The Sacred Art of Bhutan

Curators interviewed on KQED Forum by Michael Krasny, 2//25/09;

52-minute streaming audio.

A Kingdom in the Mountains Shares Its Secrets, Susan Emerling, New York Times, 2/24/08 |