Previous Chapter | Table of Contents | Next

Chapter

THE OLD CITY OF LHASA

REPORT FROM A CONSERVATION PROJECT (98-99)

| 2. F A B R I C |

| 2.1 Lhasa's Historic Urban Fabric 2.2 The Traditional Lhasa House 2.3 Materials and Construction 2.4 Life-style in an Old Manor House 2.5 The Traditional Lhasa House as a Relic of the Past |

2.1 Lhasa's Historic Urban Fabric

The ancient urban and social patterns to be found in the old city reveal much about Lhasa's cyclic historical development and the traditional life-style of its inhabitants.

The Tsuglakhang temple, as described in the previous chapter, is the spiritual and physical heart of Lhasa. In harmony with the Buddhist traditions established by Lhasa's founder, circumambulation routes lead clockwise around the Tsuglakhang, enabling pilgrims to venerate Tibet's most holy shrine and to gain merit for the next life by doing so.

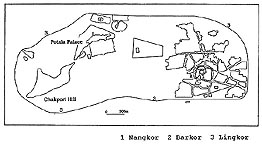

The innermost pilgrimage circle, the Nangkor, which leads around the Tsuglakhang's central temple building, was presumably established at the time of its founding in the 7th century.

The intermediate circle, the Barkor, has existed at least since the late 14th century, with its outlook and size changed and amended over the centuries. The shape of today's Barkor is largely identical to that of the late 17th century, except for alterations made in the 1960s (removal of Buddhist stupas, huge prayerwheels and other religious attributes) and in 1984 (creation of the large open square in front of the Tsuglakhang's main gate). Today, as it has been for centuries, the Barkor is also Lhasa's main bazaar street. However, in the early hours of the morning, and at sunset, a visitor can ascertain that the Barkor is still a religious circumambulation route of major importance for Lhasa citizens and pilgrims. Most practitioners do between one and three "koras" (circumambulations) per day.

The outer circle, called Lingkor, leads clockwise around the city at its pre-1950 limits, encompassing the 40-odd temples, monasteries and shrines once existant in Lhasa. These three koras determine the way Tibetans perceive and access the city, as customarily a visitor would first do a Lingkor before entering the city, then do a Barkor before entering the Jokhang. The three circumambulation routes have also in the past defined the pattern of Lhasa's urban growth axis. Over the centuries, the city grew in concentric circles around the Tsuglakhang. These layers of city quarters are entered by crooked little alleyways, lined by low, white-washed stone-and-mud houses. One-, two- and three-storey buildings would alternate with one another, so that no-one would block the neighbour's sunlight. The dense maze formed by the old city's ancient residential buildings was previously interspersed by temples, market squares, covered and open sewers, ponds, gardens, and Buddhist stupas.

2.2 The Traditional Lhasa House

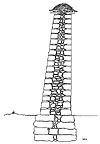

The traditional Lhasa house has a flat roof and the outer walls slope inwards, resulting in a characteristic silhouette. The white-washed facade is further accentuated by thick black frames around and little slate roofs above the doors and windows. The corners of the roof are elevated, and twigs decorated with prayer-flags in five colours signal that the inhabitants are Buddhists. Monastic buildings have additional attributes and a different lay-out, but the basic architecture is the same.

Lhasa's three main circamambulation routes

A typical Lhasa mansion (Dakpo Trumpa)

The vernacular buildings of old Lhasa can be classified into three main types: the noble house, the large residential building, and the smaller house inhabited by merchants and commoners.

All three types of buildings generally have at least one courtyard. Smaller and medium-sized buildings are often rectangular in shape.

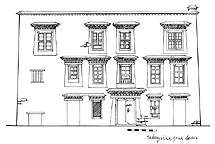

The noble houses are generally much more elaborate than the other two house types, with better craftsmanship and better materials used. The basic noble house consists of a main building, up to three floors high, and an attached outbuilding. The main building is often conceived symmetrically, and always hierarchically, with the top floor accentuated by ornate windows and balconies. The outbuilding is usually one floor lower that the main building. It is built around a large principal courtyard, with a gallery giving access to the romms on the upper floor. The ground floors of both buildings are designed to function as store-rooms and stables.

The large residence yards of old Lhasa were originally owned either privately, by rich monasteries or by the government. They probably originated as caravanserais providing temporary lodging and shelter for travelling merchants, and later became tenement yards in response to urban growth. Monastically-owned residence yards served the additonal purpose of providing central accommodation for large numbers of monks during important festivals. The traditional residence yards are less symmetrical in design, and the third floor is always built from mudbricks. The craftsmanship displayed is generally very solid, but ornate decorations are to be found only in a handful of rooms reserved for the owners, their relatives or representatives.

Traders owned or rented smaller houses that served simultaneously as residence, shop and goods storage. Usually two stories high, many of them were very well-built. Smaller residences owned or inhabited by common people were often built from mud-brick on a stone foundation and were less decorated than houses owned by nobles or merchants.

2.3 Materials and Construction

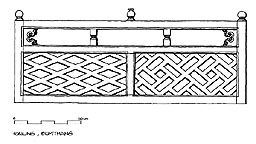

The traditional way of building is a response to Tibet's cold and dry climate, and the earthquake-prone ground. Since from at least the 7th century onwards until recently, the materials used for construction of housing in Lhasa have not changed much. Local stone, wood and earth are the basic materials, different qualities of which were used for different purposes. Slate, for example, forms the little roofs over doors and windows, while granite is preferably used for walls. Softer woods (such as poplar) are used for carvings, while harder woods (firs, nut trees) are used for structural support.

One of the most characteristic features of traditional Tibetan architecture is the battered wall. Besides giving Tibetan buildings a distinctive silhouette, the inward-sloping walls also provide extra stability in case of tremors. The sloping is created by the reduction in thickness from the ground floor wall to the top floor wall, with the inside wall remaining vertical

The walls on the ground floor, usually built from stone on shallow stone foundations, are extremely thick, often more than a metre. The walls get thinner and lighter towards the top of the building. The top floor of a house is commonly built from mud bricks; but wealthier houses would have used stone bricks for all floors. Between the meticulously-made outer and somewhat simpler inner faces,

the wall core is filled with stone rubble and then rammed with mud, straw and other insulating materials.

The masonry deserves special mention. Courses of large rectangular stones, roughly of equal size, are laid between layers of small flat stones. This technique, known as galetted rubble, gives the walls a greater flexibility in case of tremors and therefore adds to the stability of a house. The top of a wall is sealed against rain by a cornice made from slate and wood, crowned by a mound of clay.

Ceilings, supported by a pillar-post construction, are built by placing wooden rafters between the cental beams and the walls. The rafters support layers of pebbles and mud. The roofs are sealed either by stamped and oiled clay (known as Arga) or water-absorbing sand known as Tikse.

The thick walls and the filled ceilings ensure maximum insulation against the harsh temperature changes in the Tibetan climate.

Tradionally responsible for the entire construction of a house there would be a master carpenter or master stone mason, who had the title of "chimo". The client would explain the size of the house and any special needs, and the only drawing of the building needed would be a rough sketch drawn on sand or with charcoal on a piece of wood, for the client's approval. For the placement of doors, windows and designation of rooms, as well as for ceremonially initiating the construction project, a monk well-versed in Tibetan geomancy would be hired.

For the refinement of the Lhasa style of architecture, the period from the 17th century onwards is most relevant. The 17th century saw the consolidation of the lamaist state. Building projects during that period re-defined the Lhasa urban landscape. In the 18th and 19th centuries, influential aristocrats and monastic officials built opulent mansions as their residences. The concentration of wealth, political power and religious importance provided the necessary background for the formation of a tradition of master builders. In the early 20th century, contacts between Tibet and the outside world gradually increased. The advent of new construction materials obtained from outside of Tibet, first of glass, later of metal beams, and finally of cement, heralded a modernisation of the traditional way of building houses in Lhasa.

2.4 Life-Style in an Old Manor House

The most elaborate houses of old Lhasa were the homes of the aristocracy. Each was built as the residence of a single noble family, who would live there with their relatives, servants, animals and stored goods. We find a good description of a noble house in the writings of Sir Charles Bell, British special envoy to Tibet and a personal friend of the 13th Dalai Lama. In 1915, Bell stayed with the wealthy Palha family at their country estate near Gyantse. The following description of the estate gives a good impression of the life-style of the Tibetan aristocracy prior to 1959, though it must be noted that a noble house in Lhasa is only a down-sized version of the country manor.

The house at Drong-tse is built around a qudrangular courtyard. The side opposite the entrance rises to four stories above the ground [note: in Lhasa city, three stories was the rule]. On the topmost floor the members of the family live during the summer months, moving one floor down in the winter for the sake of warmth. Their sitting-rooms, bedrooms, and kitchen are here. There is a schoolroom also, to which come both the sons of the house and those of the retainers and the tenantry, but the Pa-lha boys have their own special seats. A small praying-room, where the family priests read prayers, though poorly furnished, is heated with braziers of yak-dung, the common fuel of high Tibet, where wood is scarce and coal basically unknown. Thus warmed, the family gather in it often during the cold mornings and evenings of the long Tibetan winter. All the sitting-rooms have altars and images in them, for, from prince to peasant, their religion is part and parcel of the life of the Tibetan people.

On the floor below are found the room for the two stewards, in which they do their work and pass the day. On the walls hang bows and arrows kept ready for the archery which delights the heart of Tibetan man and maid, held as it is under the blue Tibetan sky and accompanied by wine and song. On the floor are three or four of the low Tibetan tables with teacups on them drawing attention to the national beverage. Beyond are two Gönkhangs. Here, too, is the largest chapel in the house. It is known as the Kan-gyur chapel, for it enshrines a complete copy of the Buddhist canonical books, one hundred and eight volumes in all. In the floor is a large trap-door through which grain is poured into the store-room below. A kitchen for the servants, a store-room, and a large reception room, used for important entertainments, complete the tale of rooms on this storey. It was on this floor that my wife and I were lodged when on a three-day visit to Drong-tse in 1915. For our room we were given a large chapel, part of it being partitioned for our use. Behind the partition a monk could be heard off and on from five o'clock in the morning intoning the services for the Pa-lha household.

At the New Year, the more influential retainers and tenants come to offer ceremonial scarves to the head of the house. If a member of the house is present, he receives the scarves; if not, these are laid on the table in front of his empty seat.

On the floor below we are among the rooms for servants and for storage. An apartment used for housing wool runs along one side. From end to end of the other side runs a long room for housing grain. Part of the latter, however, is taken up by two open verandahs, separated by a partition wall and facing the courtyard. These spaces are used by persons of rank somewhat lower than that of the master of the house for watching the entertainments that from time to time take place in the courtyard. Convention requires that those of highest rank shall sit in the highest seats, though thereby they lose the better view of the spectacle. The nobility are accommodated with seats in the gallery, the common folk are relegated to the stalls.

Rugs, tables, &c., filled a lumber-room; in another bread was kept; in yet another was stored barley to be used for making beer (chang). I had often heard that Tibetans laid in a large part of their meat supply once yearly, in October, and here I witnessed the proof of this. For in a large room joints of yak-beef and mutton were hanging from the ceiling. The meat had been killed for nine months - October to July - but was free from offensive smell. A bedroom for the priests and various servants' apartments found place on this floor.

On the first storey are two rooms for brewing beer, a large room in which meat, barley-flour, oil, and such-like are stored together. Along the other sides we find rooms used for peas, barley, and other grain.

After the Tibetan custom a strong wooden ladder with steep, narrow steps leads to the courtyard below. At the top of the ladder, in a recess on each side of it, stands a praying-wheel, as high as a man and of ample girth. Thousands upon thousands of incantations and prayers are printed and pressed together within these great cylinders. At the foor of each sits an old dame, who makes it to revolve, and in so doing sends upwards this mass of prayer and offering for the benefit of the world at large and the Pa-lha household in particular.[...]

Round the courtyard, under the projecting verandahs of the floor above, are stables. At the back of these are rooms for storing hay. [...]

The room in which we were offered the usual tea, cakes, and fruit was, as so often happens, a chapel and a sitting room combined. But it was unusual in that it faced towards the north. Tibetans usually arrange that their best rooms shall catch as much sunlight as possible.

2.5 The Traditional Lhasa House as a Relic of the Past

The elaborate life-style of the aristocracy has now all but disappeared. Changes in society have led to the decline of private ownership, and population development has created increasing demand for inexpensive public housing. The advent of steel and cement has made it possible to build faster and comparatively cheaper than before. These factors have led to the decline and near-disappearance of the traditional skills, and have also contributed to a drastic change in appearance of the city of Lhasa.