Introduction | Table of Contents | Next

Chapter

THE OLD CITY OF LHASA

REPORT FROM A CONSERVATION PROJECT (98-99)

| 1. S E T T I N G S |

| 1.1 Geographical Setting 1.2 Historical Setting 1.3 Social Development 1.4 Lhasa's Uniqueness |

The city of Lhasa is located in the southern part of the Tibetan high plateau at an altitude of 3650m above sea level and on roughly the same longitude as Cairo. The valley in which Lhasa is situated is formed by the river Kyichu, a tributary of the Tsangpo (which is known as the Brahmaputra in India). The dominant peaks surrounding Lhasa range between 4400m and 5300m above sea level. The city itself is built on a plain of marshy grounds, dominated by the three hills, Marpori ("red mountain"), Chakpori ("iron mountain") and Barmari ("rabbit mountain"). The Lhasa valley is sheltered from the harsh winds that roam much of the Tibetan plateau, and the city benefits from a micro-climate that can be termed moderate. Recent maximum summer daytime temperature was 28 degrees celsius, wintertime temperatures average -15 degrees celsius at night. The air is extremely dry throughout most of the year except during the summer rainy season (July-August). Lhasa has more than 300 days of sunshine a year.

|

In the Lhasa valley, to the north of the city area near present-day Sera monastery, the neolithic settlement of Chugong was excavated in the 1980s. Chugong dates back to about 1500 - 2000BC. Bronze and stone tools were found, leading to the assumption that the Chugong people practised agriculture, animal husbandry and hunting.

Tibetan recorded history began in 127 BC when the first emperor Nyatri Tsenpo (gNya'.khri.btsan.po) was crowned. During the first half of the 7th century AD, the 33rd Tibetan king, Srongtsan Gampo created an empire that largely corresponds to the present-day extension of the Tibetan cultural realm (incorporating Tibetan-speaking areas in India, Nepal, and China's Sichuan, Qinghai and Yunnan provinces as well as the Tibetan Autonomous Region itself). At that time, Tibetan society was presumably the culture of nomadic warriors, somewhat comparable perhaps to the 11th century conquering Mongols. These warriors were in constant territorial warfare with their neighbours, China's Tang dynasty and the Uighur northern tribes, and at times even with Persia. The Tibetan royal court moved regularly throughout the country, from summer camp to winter camp.

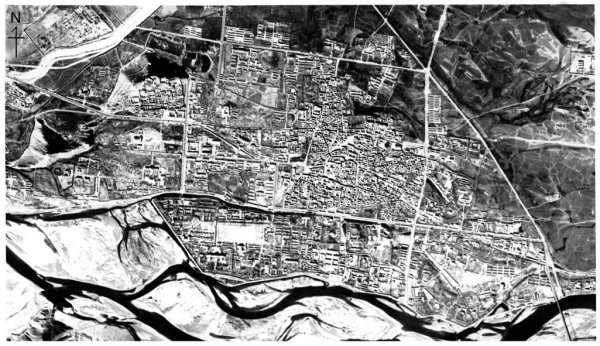

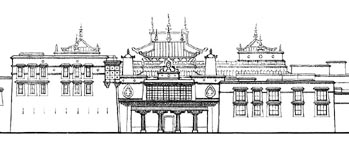

Central Lhasa ca.1940s, Potala Palace in background Far from the Yarlung valley where many Tibetan kings were customarily buried, emperor Srongtsan founded Lhasa as Royal camp site in ca. 633. Originally the city had been named Rasa, meaning simply "fortified city". Various factors contributed to the establishment of Lhasa as semi-permanent royal capital. Two of the five queens of Srongtsan fullfilled an ancient prophecy by bringing Buddhist images and ritual knowledge to Tibet. Apart from Srongtsan's own palace (at the site where today the Potala Palace stands), the capital of Rasa consisted of several Buddhist temples and shrines, the queens' palaces, and presumably quarters for servants, labourers, warriors and merchants. Several imperial strongholds are known to have existed in different parts of Tibet during the flourishing of the empire period (7th-9th century). Lhasa remained important despite subsequent kings having established their courts elsewhere because of the Rasa Trulnang Temple (miraculous self-manifest temple of Rasa), later also called the Lhaden Tsuglakhang (Lhasa Cathedral) or simply Jokhang (house of Jowo, precious image of Buddha). This temple was founded in ca. 641 at the behest of princess Brikutri, the Nepali bride of king Srongtsan. The Rasa Trulnang was closely modelled on Indian Buddhist temples that were famous at that time, and was several times restored under Srongtsan’s successors on the throne. Tibetan scholars name the 7th-8th century Vikramasila temple, which itself was destroyed in the 12th century, as a model for the Trulnang. Many similarities in lay-out and details also exist between the Trulnang and the Indian Nalanda monastery, and with the Ajanta caves. The Jowo image that eventually came to be housed in the Trulnang temple, said to have been cast during Buddha's life-time, was the bridal gift of princess Wen-Cheng, Srongtsan's Chinese wife. Even as Lhasa's political influence wained after Srongtsen's death, the Trulnang temple's importance was recognized again and again during the following centuries, giving Rasa the status of a Holy City and its new name Lhasa, the place of the gods.

|

In the mid-9th century, the Tibetan empire fell, and the kingdom disintegrated into independent fiefdoms and regional power centres. Lhasa no longer had much political importance, but because of the Trulnang/Tsuglakhang temple, the city remained an important destination for pilgrims and renowned Buddhist teachers. In the early 15th century, one of Tibet's most important religious teachers and scholars, Je Tsongkhapa from Amdo, founded the great monastic universities of Sera and Drepung on the outskirts of Lhasa. Lhasa soon became an important seat of learning, attracting students from as far away as Mongolia who studied Buddhist dialectics, astrology, medicine and calligraphy, and practiced debate and meditation. Besides being a major cultural centre, Lhasa was still a major trading centre, being the cross-point for trading caravans from Nepal, India, Ladakh and muslim Central Asia. In the 17th century, the Tibetan regions become once more unified under the Fifth Dalai Lama and his Mongol patrons. The Dalai Lamas were the reincarnated de-facto heads of Tsongkapa's reformed Gelugpa ("virtuous") sect. The Fifth Dalai Lama, Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso (1617-1682), established a central Tibetan government named Ganden Podrang ("earthly palace representing Tushita heaven") and re-modelled Lhasa as his capital. He was responsible for the building of the Potala Palace, and he extended the Tsuglakhang temple to its present-day dimensions. In 1913, the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Thupten Gyatso (1876-1933), declared an end to China's status as suzerain (or patron) of Tibet, and began the modernization of his mediaeval realm. Lhasa soon had a post office, a hospital, a permanent British representative, and a small hydro-electric powerstation. Despite setbacks, the modernization continued, and in 1947-48, the government employed the Austrian engineer Peter Aufschnaiter to survey the city because of plans to improve power supply and irrigation.

In 1950, Mao Zedong's People's Liberation Army crossed the boundaries established by the 13th Dalai Lama between Kuomintang China and the Tibetan areas under administration of the Ganden Podrang government. Lhasa decided to take up Beijing's offer to become an Autonomous Region of the newly-established People's Republic of China, under the 1951 17-point agreement in which a high degree of autonomy for Tibet is stipulated. In 1959, popular revolt against communist reforms led to several days of warfare in Lhasa, causing much destruction and suffering. The 14th Dalai Lama fled to India and almost 40 years later is still a guest of the Indian government. With most of the ancien regime having also departed, communist reforms were fully implemented in Tibet. Property was nationalized, and agricultural production radically re-organized under a commune system. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), monasteries were destroyed and Tibetan customs and traditions branded as feudal and forbidden. Since the political reforms that began in 1978, Tibetan religion and customs have slowly become rehabilitated. By the 1990s, the economic reforms that already transformed most of China had also reached Lhasa, resulting in rapid modernisation of the city and a growing prosperity for many city dwellers.

|

Lhasa was perhaps old Tibet's only true city. Today, Lhasa is still the biggest urban settlement in the Tibet Autonomous Region, and has retained its importance as a holy city for the entire realm of Lamaist Buddhism. Lhasa also has been, and to some extent still is, an extraordinary cultural centre, where traditional medicine, astrology, philosophy and Buddhism could be studied in great institutions of learning.

The physical remains of the old city represent a living witness to history. Lhasa’s buildings are a rare example of urban Tibetan architecture, and the old city allows the visitor to view developments that originally took place over centuries by simply taking a few steps.