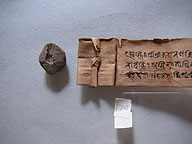

During

the summer of 2005, the conservation and digitisation of 400 rolled palm

leaf manuscripts with clay seals (fig. 01, below) housed at the Asa Archives

in Kathmandu was carried out over a period of 6 weeks.

fig.

01

fig.

01 |

|

The

Asa Archives is a public library named after the late Mr Asha Man Singha

Kansakar, father of the late Mr. Prem Bahadur Kansakar (1917-1991), a

prominent activist, social worker, educationist and Newar writer who had

founded several social, cultural, literary and educational institutions.

Their personal collections and later additions of the manuscripts became

the base of the Archives which opened to the public in 1987. The archives

houses more than 6,700 manuscripts, including Buddhist and Hindu texts,

medical texts, manuals of magic and necromancy, astrology, astronomy,

Vedic, Purana and Tantric text. Land grants written on rolled palm leaf

manuscripts with clay seals are unique to Nepal.

The Asa

Archives is one of the very few institutions in Nepal to have digitised

nearly its entire collection of manuscripts. The one exception was the

collection of the rolled palm leaf manuscripts which were not digitised

because of the difficulty of even opening them without causing damage.

An important matter for consideration was in what form the objects should

be housed after the conservation. From the conservator’s point of

view, ideally they should retain the original form. However, for easier

access to the text and to avoid further damage during the unrolling and

rolling, keeping the objects flat was also considered.

This problem was solved by digital photography which was to be carried

out as soon as the conservation treatment of each roll was finished in

order to prevent unnecessary unrolling more than once.

|

The Rolled Palm Leaf Manuscripts

“Since palm leaf is not native to Nepal, one can presume that the

tradition of writing in this medium was introduced into the country from

the Indian plains probably during the Lichchhavi period (330-879 AD)”

(Pal & Meech-Pekarik, 1982, p. 95).

Leaves of Talipot (Corypha umbraculifera Linn) and Palmyra (Borassus flabellifer

Linn) were both found among the manuscripts in the Asa Archives. Talipot

is far superior as writing material; longer, wider, lighter in colour with

a smooth and supple surface, whereas the Palmyra leaf is shorter, narrower,

thicker, corser and tends to become brittle and prone to physical damage.

There are approximately 1000 catalogued and 300 uncatalogued rolled palm

leaf manuscripts in the archives, making it the largest collection of its

kind in Nepal. They are land grant documents commonly called tamsuk

in both Nepali and Newari (Nepal Bhasa). The oldest tamsuk among

the 400 conserved is dated 1337AD (Newari Samvat 457) and they run up to

the 17th century. The languages used are Nepali and Newari (Nepal Bhasa)

mixed with Sanskrit. The scripts generally used are Bhujimmola, Devanagari

and Prachalita.

Out of the 400 tamsuk the longest was 1m 27cm excluding the part

which was folded several times under the seal. The shortest complete manuscript

was 25.7cm. The average length was 55.2cm. The natural shape of a palm leaf

is generally widest in the middle and tapered towards both ends. The width

in the middle varied between 1.5cm and 5.5cm.

At the head of each tamsuk, an unfired dark grey clay seal varying

in design and in size between 8mm and 2.8cm, is affixed over a knot of palm

leaf strips which secured

|

fig.

02 |

the folded

part of the document (fig. 02). Sometimes there were short

texts written here, but quite often they were blank.

The tail end is generally cut off a little and folded once. This folded

line was found to be weak and many were broken off completely.

A few tamsuk show half a design of intricate patterns at either

the head or the end of the document.

“The agreement was written in two identical copies on the right and

the left side of a single strip of palm leaf, the two copies being separated

by the fleuron. Upon ratification of the agreement, each party was issued

with one part” (Kölver & Shakya, 1985, p. 26).

The text was normally written on one side only but occasionally codicils,

brief notes or numbers were added on the verso.

The text was written on the surface, presumably with a reed pen and carbon

based ink, rather than incised.

|

Condition

of the tamsuk

151 rolls out of 400 (38%) were damaged to a various extent by mice (figs.

03 and 04, below). Unexpectedly only 12 rolls were damaged by insects (fig.

05, below). A few suffered from mould damage especially around and underneath

the seals.

fig. 03 |

fig. 04 |

184 rolls (46%) had previous cellotape repairs. Sometimes the entire surface

of the palm leaf was covered with cellotape (figs. 06 and 07, below).

The clay seals of 175 rolls (44%) were either completely missing, separated

from the palm leaf strip on which the seal was partially imbedded, or cracked.

Many manuscripts suffered numerous vertical cracks, folds and tears as the

result of the rolls having been pressed down over the years.

Surprisingly the condition of the text itself was found generally sound,

apart from some smudges or frayed surface making the text illegible.

Conservation

Aims

The aim of the conservation for this project was to stabilise the objects

to prevent any further damage, and to prepare them for digital photography.

Therefore the minimum intervention was to be carried out for the actual

physical conservation which was concentrated on cleaning, removing all

the previous repair tapes, joining and repairing the fragments, treating

mould, stabilising folds by providing support from verso, consolidating

frayed layers and parts and consolidating or joining the damaged clay

seals.

It was hoped to find the most suitable storage method for the conserved

manuscripts where the fluctuation of the temperature and humidity is significant

and no artificial environmental control is a possibility.

Conservation

Procedures

In order to unroll the tamsuk without damaging them, it was necessary

first to humidify them. Prior to humidification, the measurement of the

diameter of each roll was taken so that when the treatment and the photography

was finished it could be rolled back to the original diameter, which varied

from 1.8 cm to 6cm.

Humidification was carried out in a shallow polypropylene tray large enough

to fit nine tamsuk. 300cc of filtered water was added to 6 layers

of 55g/M2 local hand made Lokta paper (Daphne bholua), a sheet of Capillary

matting was placed over this and another 50cc water added. A sheet of

Sympatex was placed on top of the Capillary matting. A sheet of Bondina

(unwoven polyester) was placed over this, then 9 tamsuk. A sheet

of glass was placed over the tray. The use of Sympatex together with Capillary

matting allows the humidity to reach the objects uniformly without the

risk of liquid penetration (fig. 08, above).

The duration of the humidification was 90 minutes which was found to be

sufficient for the tamsuk to be opened without difficulty. They

were then transferred and sandwiched between two sheets of Bondina and

four layers of blotter, the outer two of which were sprayed damp with

filtered water (fig. 09, above). A wooden board was placed with weights

which were stone mortar and pestles wrapped in heavy Lokta paper for protection

(fig.10, above). This process was necessary to keep the rolls flat for

further conservation treatments and subsequent photography.

The both surfaces

of the palm leaves were cleaned with cotton swabs moistened with ethanol,

avoiding the text area. All the cellotape, masking tape and other old

repairs were removed and residue cleaned mostly with acetone (fig.11,

above). All the tears were repaired using 100% Kozo fibre Japanese papers

of different weights which were toned with Cartasol K dyes (cationic,

direct dyes developed especially for predominantly wood-free pulp paper)

in various shades. The dyes have been used in the British Library for

quite some time, have shown good colour fastness and are stable. The vertical

folds and creases were also supported with repair paper from the verso

(figs. 12 and 13, above). The loose or faulty seal attachments were also

strengthened (fig. 14 and 15, below).

Methyl cellulose

was chosen as an adhesive mainly in consideration of climatic conditions

in Kathmandu, where during the summer monsoon months relative humidity

stays around 60% or over and the temperature 28-310 C.

Cracked or broken seals

were repaired using Paraloid B72 in acetone (figs. 16,above and 17, below).

Photography,

Measuring, Record Keeping and Storage

The camera used was Fuji Fine Pix 52 Pro with Nikon Lens AF-S NIKKOR 24-85mm.

For palm leaves over 66cm, two photographic frames were taken and carefully

joined together

at the editing stage. The photograph of the verso was also taken when

there was writing of any kind. Separate close up photographs were also

taken for each seal which might render further research easier. The measurements

of the length and the width of three parts (head, middle and tail) were

recorded before the tamsuk was rolled back in the same way starting

from the left seal side so that both the seal and the text could be protected.

The record of the diameter of each roll prior to the humidification was

referred to, and the same diameter retained as far as possible. The roll

was tied temporarily with a piece of twisted Lokta paper cord and left

to air dry until next day (fig. 18, below).

Completely dried

manuscripts were wrapped in 14g/M2 Lokta paper softened by hand-squeezing.

New digital catalogue numbers were recorded on the archival label and

pasted on the Lokta wrapping sheet. Another label of the same number was

also attached inside each compartment of the alkali buffered archival

box custom designed and assembled in Japan to accommodate 80 rolls with

double outer walls which act as a buffer for the change of temperature

and relative humidity in the storage room (fig. 19, above). It is extremely

important to provide the safe enclosure which can sustain the stable micro-climate

especially in countries where there is no other means of controlling the

environment of the entire buildings. The double wall structure constructed

with strong archival board with a tight fit lid should also discourage

further attack by mice and other insects. The polypropylene coated board

keeps out atmospheric pollution and is waterproof.

Inside the lid, a sheet of SHC (Super Humidity Controlling) board is incorporated

which acts as buffer for the humidity fluctuation to certain degree as

well as absorbing the harmful gasses emitted from the objects themselves.

Conclusions

Having treated 400 rolls in various unravelled states we had a rare opportunity

to observe closely how the structure of the sealed manuscripts was made.

fig.

20

fig.

20 |

|

One

can imagine the kayasthas (official scribes) in Mediaeval Nepal

carefully choosing a prepared and polished palm leaf, short or long, wide

or narrow depending on the length of the text he is about to record, from

a bundle of palm leaves which must have been carried from Indian plains

partly on the backs of men over passes and through jungles. He would then

write out the document, fold the head part of the leaf several times and

make a small incision for the palm leaf strip to go through and tie a

knot to secure the folded part. Finally, he would take a small amount

of round soft clay to impress his particular seal over it (fig. 20). When

the seal was dry the palm leaf would be rolled tightly for safe keeping.

What we have now under safekeeping is the collection of rolled palm leaf

manuscripts covering a period of several hundred years.

Approximately one third of the collection at the archives was stabilised

and future damage and deterioration minimised as far as possible. They

are all now housed in the archival boxes.

The very clear digital images of all the texts, seals and any additional

writings on the verso have been recorded.

It is hoped that this project will continue for the next two years. When

it is finished, reseachers will have a fuller access of the contents of

land grants of the Kathmandu Valley, and it is not improbable that this

could shed new light on historical, economical and social conditions of

the period.

The

project for 2005 was partially funded by the Japan Foundation.

The following companies kindly supplied the materials at no cost.

Japan Archival Enclosures Co., Ltd. specially designed and assembled archival

boxes.

Masumi Corporation supplied various papers for repairing.

Clariant Japan Co., Ltd. supplied Cartasol K dyes.

|