asianart.com | articles

Articles by Ian Alsop

Download the PDF version of this article

This article first appeared in December 1973 (Poush VS 2030) in the first issue - Vol. I, No 1 - of Contributions to Nepalese Studies, published by the Institute of Nepal and Asian Studies (INAS) of Tribhuvan University in Kirtipur (later renamed the Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies (CNAS)) [A]. We have reproduced it here as it is found in print with the exception of a few minor typos, which have been corrected. (For those interested, a scan of the original article can be found here: http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/contributions/pdf/CNAS_01_01_02.pdf.) The original notes, numbered 1-11, are also as found as in the printed article: however, we have added a few further notes, numbered by letters shown in red color, to make comments from the present day. The illustrations in the print version were found at the end of the article. We have moved the thumbnails of these images to the correct place in the text and supplied our usual asianart.com "large image pages" (LIP) for each, where the original image caption can be found with an enlargement of the original image scanned from the printed version; in some cases we've replaced the scanned print image with a scan of the original photo, in considerably better resolution. We've taken the liberty of adding detail images from other photos in our archives. All the detail images found in the large image pages, have only been introduced in this online version; they are not found in the print edition. We have also added one or more new images which will be numbered with the letter A and referenced in the text in red, for example: Fig. 17A.

March 02, 2022

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

Stella Kramrisch, a noted authority on Nepalese art, ends her excellent book Art of Nepal with these words:

"To this day Nepal has a living myth. It is enacted throughout the year in the succession of seasonal rites and festivals. No living art supports them any longer."[1]

This is a common assumption, yet it is one which the authors of this report feel to be incorrect. Indeed, it might well be said that Nepal, alone among her neighbors, does indeed have a living art which is the continuation of an ancient tradition.

Of all the ancient art forms still practiced in the valley of Kathmandu, the one which is most vibrantly alive is that of image casting in metal. The city of Patan is the modern as well as traditional center of the practice of casting, and within the city itself it is the Newar community of Oku Bahal to which Nepal's most respected and skilled sculptors and casters belong. This report will focus its attention on these men and their traditions, on the past which formed their vision and technique, on the changed present in which they work, and on the future of their art which so many assume to be dead.

1. History.

The Nepalese tradition of casting images in metal began many centuries in the past. Nepalese art in all its forms, both Buddhist and Hindu, was basically a child of the artistic genius of the great Indian artists of ancient times. According to Rustam J. Mehta, the art of image casting reached Nepal from India during the regime of the Imperial Guptas in India (A.D. 320 - 600)[2]. Although it is difficult to place a Nepalese metal sculpture so early in time, there is no doubt that the artistic vision of the Guptas did indeed have a strong influence on the casters. The influence of the artists of the Gupta period upon Nepalese stone sculpture of that period is obvious, and it was undoubtably transmitted to the casters through that medium.

Two later Indian artistic periods also show their influence on Nepalese metal sculpture, the Pala and Sena (8th to 12th centuries). It was under the stimulus of the Indian artists of this period that Nepalese image casting grew to a major art form and flourished in the Valley of Kathmandu.

As the art of India was dying under the sword of Muslim invaders, the seed that the genius of Indian artists had planted in the soil of Nepal matured and flowered. Nepalese art began to take its own direction, and the influences of the Indians began to become mixed in with an unmistakably Nepalese style. Nepal became more than a transit point for ideas and styles moving from India to Tibet and China, and took on an importance in its own right as a cradle of great art. Newari craftsmen gained a reputation among the Tibetans and Chinese as artists of the highest quality, and colonies of Nepalese artists were imported into these countries to paint and sculpt, and also to teach the Tibetans and Chinese the techniques of their art. And just as the Nepalese had adopted Indian styles and then transformed them to suit the native vision, so did the Tibetans and Chinese take the styles given to them by Newari artists and transformed them to distinctly Tibetan and Chinese styles. Just as Nepal influenced the art of these two countries, so over the centuries did the Tibetan and Chinese styles return to influence further the art of Nepal. This flux and change in the style of Nepalese sculpture is summed up by Ananda Coomaraswamy thus:

"In the older Nepalese figures the Indian character is altogether predominant, and there is no suggestion whatever of anything Mongolian: they recall the work of the Gupta period. They are characterized by a very full modelling of the flesh and almost florid features: the bridge of the nose is markedly rounded and the lips full. On the other hand, those of a later date, and up to modern times, are no longer robust and fleshy, but svelte and slender-waisted and more sharply contoured; the nose became aquiline, sometimes even hooked, the lips clear-cut and thin, and the expression almost arch . . . To sum up these distinctions, the art of the earlier figures is plastic and sculpturesque, while that of the latter has more the character of chasing and suggests the hand of the goldsmith rather than a modeller."[3]

As this summation suggests, the history of Nepalese art is one of flux and change, of the adoption and transmutation of neighboring styles. Nepalese craftsmen were first the pupils of Indian artists of the distant past, then served as the teachers of the Tibetans and Chinese, and then, more recently, again became the pupils of these northern neighbours. In the scheme of Asian art history, Nepal was at the center collecting and distributing the techniques and styles of the cultures which surrounded her. But while these older and, some would say, greater, cultures disappeared and were destroyed, the culture and art of Nepal survived.

2. The decline of surrounding traditions; the survival of casting in Nepal.

The tradition of Indian image casting was dealt a mortal blow by the waves of Muslim invaders who swept the subcontinent periodically and signalled the end of the Gupta, Pala and Sena traditions in the north of India; these of course were the artistic traditions which most affected the artisans of Nepal. With the death of these styles in the north of India and the decay of the great Chola dynasty tradition in the South, the Indian art of image casting went into a long decline from which it has never recovered. With the modern period of Indian history beginning with the takeover by the British, India turned away from her neritage of philosophy and art and concentrated her energies on the forging of a modern state. The result has been the loss of a great art. As Rustam J. Mehta writes in his Masterpieces of Indian Bronzes and Metal Sculpture: "Made in large numbers, the images of the 18th century to this day, are poor specimens of a decadent style, a hollow mockery of the great tradition of the past, the one-time skill and aesthetic vigour of the image makers of old . . . The once great art of metal sculpture and casting in India is dead".[4]

Cast-metal images are still being manufactured in India, but they are largely copies of pieces now being made in Nepal; these pieces can be hardly considered works of art, for they are not sculptured, but copied through the use of molds. So great has been the decline of Indian artistry that most of these pieces are no longer made through the process of lost wax but produced in halves and then welded together.

While the art of image casting in India was dying, the tradition which Indian artists had begun was still being continued in Nepal, China and Tibet. But just as medieval history saw the undoing of the great Indian tradition, so did modern history put an end to the indigenous tradition of religious art in China and Tibet. Religion and religious art have no place within communism, and the rise of that social system within China sounded the death knell for her religious art forms. And as communism expanded from its base within China and eventually swallowed Tibet in a process which ended in 1959, another traditional art form was faced with destruction. For although many of the refugees who entered India after the Chinese takeover of Tibet were artists of the first rank, it seems that image casters were not among them.

That leaves Nepal. Nepal alone among her neighbours has managed to preserve the art of image casting throughout the ages; the reasons for this remarkable survival are several.

One reason is geographical; Nepal's isolation from the plains of India spared her the sword of the Muslim invaders who devastated India in medieval times, As Mehta writes; "Fortunately for the culture of India, the iconoclastic invaders did not penetrate every nook and corner of this vast subcontinent and in isolated regions like Nepal and Tibet, the ancient art of metal sculpture and casting continued to exist."[5] Had the civilization of the valley of Kathmandu been situated in the Tarai, the art of Nepal would no doubt have died with that of India.

Just as Nepal's physical isolation from India protected her from invasion many centuries ago, so her historical and cultural ties with India, and the great barrier separating the valley of Kathmandu from Tibet in the north protected her from any change of another invasion in more recent history. China's takeover of Tibet was based on the claim, ages-old, that Tibet was essentially under the political suzerainty of China. No such claim could be made on Nepal whose status as an independent nation was more firmly established than that of Tibet, and whose cultural and historical ties with India were more ancient and binding than those she has had with China, whereas, of course, the reverse was the case with Tibet.

Although the casting of metal images has an unbroken tradition in Nepal, this tradition has gone through fluctuations over the centuries. In a religious art, style, quality and quantity of production depend not only upon the artist but also upon the patron. In Asia, the greatest periods of artistic fertility within a single area occurred when that area was controlled by a ruler who both kept peace in and provided security for, his Kingdom, and also showed a fondness for the arts and a dedication to religion.

Thus, in Nepalese art history, as in Indian and Chinese, periods are named after the ruler or rulers who oversaw and patronized the rise of, a particular style. Until the rise of the Gorkhas, there were five such periods between the Licchavis and the Mallas (9th to 12th centuries), and the early Malla (13th to 15th centuries), and the late Malla period (15th to 18th centuries.) When the three valley Kingdoms of the Newari Halla Kings were captured and consolidated under the Gorkha King, Prithivi Narayana Shah, in 1768, a difficult period started for the Newari artists of the Kathmandu valley. For, as Gopal Singh Nepali writes in his book The Newars, "With the overthrow of the royal Mallas, the patrons of fine arts, the Newar artisans ceased to receive encouragement from the Gorkhas who idealised a different branch of human excellence - the art of chivalry."[6]

Thus the Gorkha period has been a difficult one for the artists of the Kathmandu valley. State patronage, always a prerequisite for great art in Asia, had all but disappeard, and the image casters as well as all the other artisans, had to fall back upon private patronage. The sudden drop in Royal patronage caused the atrophy of several of the art forms for which the Newars were most famous, notable temple construction and stone carving, and to a lesser degree, wood-carving. The nature of image casting in metals, however, allowed this art form, along with painting to survive, for these has always been a demand among religious Newars for images and paintings for household use.

Thus, throughout the reign of the Gorkhas until modern times, the tradition of image casting survived, in a somewhat atrophied form, through private patronage. That the art could maintain itself at all, much less at a high level of quality during this period is largely due to the cultural solidarity and religious spirit of the Newari people.

Recently the ancient tradition of image casting has received a major boost. This is due largely to two recent developments: the flight of many religious Tibetans from their homeland, and the rise of tourism in the valley of Kathmandu.

When the Tibetan refugees left Tibet and settled in India and Nepal, they brought with them their characteristic religious devotion but not their temples nor the images of the gods which they so revere. Immediately upon settling in India, they began to rebuild the material framework within which their religion thrives, and, when it came to images, they turned to the Newari artisans of Patan for the work they desired. Almost all of the images in modern Tibetan monasteries and temples in Nepal, India, and as far away as Switzerland have been sculpted and cast by the image casters of Patan. The large image of Padmasambhava in the Karma Kagyupa gompa at Swayambhunath is an example of such patronage.

1. Oku Bahal

When art historians speak of Nepalese image casting, they are in essence speaking of the work of a group of artisans who have worked for centuries in Patan, the 'city of fine arts', in the Kathmandu Valley. Within Patan itself, these artists are further localised; the two centers of image casting in Patan are two Buddhist communities of the Bare or Vanras caste of Newari Buddhists at Oku Bahal and Nag Bahal. These two connumities have traditionally been the centres of metal casting, and they still are. Oku Bahal is the more productive of the two in terms of fine quality pieces, although several excellent copies of antique statues have been produced recently in Nag Bahal. This report will focus on the traditions and present day work of the artists of Oku Bahal.

The estimated total population of Oku Bahal is 1800 to 2000 persons. Of these, approximately 700 are 'jains', or men who have received the Chura Karma initiation in the Vihar. The Bahal community system is said by most scholars to be a left-over from the times when the Sakya people, who are said to be the original descendants of the original followers of Lord Buddha Sakyamuni, were an entirely monastic community. Thus many of the social customs, such as the Chura Karma initiation which is a perfunctory admission of a young boy into the community of monks, are reflections of the practices of ancient times. The Bahal itself is a group of dwellings surrounding a central temple, and as a communal living plan it is unique to the Vanras, or Sakyas, as they call themselves and the Bajracharya, the priestly caste of Newari Buddhists.

The population of Oku Bahal, with the exception of three or four Shrestha Hindu families and a few Jyapoo who have come to work in the casting shops, is entirely made up of Sakyas.

It is estimated that approximately 60% of the families of Oku Bahal are involved in casting (as opposed to perhaps 15 to 25% in Nag Bahal);[7]. This work is largely image casting, although bronze lotas and other vessels and implements are also cast.

The rest of the population is engaged in silverworking, goldsmithery (the traditional Sakya caste occupation), with a large number engaged in business, primarily curio business. The curio business in the valley has always been a Newari domain; one estimate places 75% of the curio business in the Kathmandu valley in the hands of the Sakya Newars, and, to a lesser extent, in the hands of the Vajracharya. This estimate may be somewhat too high, but even to a casual observer it is obvious that a large percentage of the curio businesses in Nepal are run by Sakya Newars.

Besides the primary occupations listed above, there are three doctors, all at present away from the Bahal, and a few tailors; there are no government employees.

The centre of the spiritual life of the Bahal is Rudhra Barna Mahavihar, whose main temple is dedicated to Lord Buddha, or Kwa Pa Aju, as he is known in Newari. It is in this Vihar that the young boys of the community receive their Chura Karma initiation, alluded to earlier. This initiation as well as other religious events, is overseen by Bajracharya priests, who select the auspicious date for a ceremony and then come from their own Bahal to perform it. There are two Bajracharya Bahals in Patan, Binchy Bahal and Bu Bahal; the Bajracharya who serve as priests for the Sakyas of 0ku Bahal are from Binchy Bahal.

The well-knit community spirit which pervades the Sakya Bahals of Patan is a major factor in the survival of the art of casting to the present day. With the change in patronage from Royalty to private persons and businesses, the economic organization of the community has had to change in order to meet the new markets for fine sculptures. An example of this change can be seen in the recent history of one family of 0ku Bahal, that of Jog Raj Sakya.

Jog Raj Sakya's father was a goldsmith, the traditional Sakya caste occupation. Jog Raj, in turn, took up the work of casting utensils and wine pots, primarily in bronze. Until the Nepali year 2007, the family was engaged in manufacturing these cast goods. After that year, they moved into the business world, first becoming dealers in the items they used to produce, cast pots and utensils, and then, in 2018, moving into the curio business, a move prompted by the influx of tourists. Eventually the curio business took over their interests entirely; at this time almost all of their goods for sale are the statues cast by their fellow Sakyas in 0ku Bahal, although they also sell handicrafts manufactured in Nag Bahal. At the present time the curio business, centred in several shops around Mahaboudha temple in 0ku Bahal, is run by Jog Raj's two eldest sons, Jagat and Puspa Raj Sakya.

The flexibility and business acumen of the Sakya people has been in large part responsible for the modern renaissance of image casting in Nepal. For as the demand for fine new art pieces began to appear, the Sakya showed themselves willing to accomodate their businesses to this new market, as the above brief history of one family shows. Thus the entire system of production and marketing of the pieces produced by the sculptors of 0ku Bahal remained in the hands of the residents themselves, and the casters, with the able business instincts of their relatives in the shops exploiting the market for their pieces, were able to concentrate on their own creative process.

2. The Casters: Manjoti Sakya and Bodhi Raj Sakya.

With the advent of the tourist expansion in the valley and the rise of the curio industry, the number of casters and sculptors in Oku Bahal has increased enormously. By and large these artisans are a modern phenomenon, drawn to the trade by the lucrative returns to be gained from manufacturing images: they are first generation casters, whose fathers were either silver or goldsmiths, or makers of cast pots and utensils. Despite the fact that many of them are not well-trained, several of these first generation artists show a great deal of talent and ability. But by and large they do not equal in skill the casters for whom the art of image making is a family tradition.

Of the traditional casters of Oku Bahal, the authors of this report have chosen to focus on two, Manjoti Sakya and Bodhi Raj Sakya. Although these two men share a sense of beauty and high skill in sculpture, there are differences between their work and the approach to it, especially in terms of the patronage through which they earn their living; for whereas Manjoti relies on the private and religious patronage which sustained the casting tradition after the fall of the Mallas, Bodhi Raj has turned to the new business patronage for his income.

Fig. 1 Manjoti Sakya, who lives in the compound surrounding Mahaboudha temple, is one of the most skilled and respected image casters in Oku Bahal, or, for that matter, in the whole of Nepal. Casting images has been the occupation of his family for longer than that of any other in Oku Bahal; to his knowledge, the tradition goes back as far as his great grandfather. He himself was taught by his father, Pancha Joti Sakya, who died approximately ten years ago at the age of 80. Manjoti himself is about 55 years old (Fig. 1).

Manjoti works in a team with his brother, Tej Joti, who is 52, Manjoti is responsible for all the actual sculpting work in wax, and also for covering the wax image in clay, while Tej Joti handles all of the oven work and performs the actual casting itself.

Technically speaking, Manjoti and Tej Joti use the same casting procedures used by their father, and, no doubt, their grandfather and great grandfather. An exception to this is that they no longer cast in copper, due to the fact, they say, that it requires too much concentration. The last copper piece undertaken by the brothers was an 18 inch Buddha figure, cast on private commission about sixteen years ago. Now they cast only in brass and bronze, preferring brass because it is somewhat less difficult to cast than bronze and easier to engrave. Tej Joti does not mix his own metals like his father, he buys both the brass and the bronze in the form of sheets, wire and old plates from the market in Kathmandu.

Although the techniques of casting have not changed in the family from the time that Manjoti's father was working, there have been several changes in methods of sculpting, largely brought on by the advent of photography, and also by a slight shift that has occurred in the type of patronage under which father and son have worked. Manjoti's father sculpted images almost exclusively for temples, commissioned by either a very rich single patron, or by a group of people who worshipped at that temple. As a result, his images were usually rather large, and also unique, so that he never took a das, or wax mold, for an image. Manjoti, on the other hand, occasionally does take a das of a wax figure, for his pieces are smaller in size and often more than one is ordered. Although Manjoti does still cast many images for temples, a large part of his work now consists of smaller pieces undertaken on private commission. When Manjoti does sculpt an image he generally charges less for a temple than for a person's house; this practice was also adhered to by Manjoti's father. As a result of the rise in private commissions, Manjoti has estimated that his income is slightly higher than that of his father. At any rate, he has stated that his father was always extremely busy and never without an order, as is certainly the case with Manjoti himself.

Most of Manjoti's father's commissions came from fellow Newars, and certainly a majority of the pieces that Manjoti sculpts are also for Newars; but he has also been a beneficiary of the Tibetans' flight from their homeland. It is undoubtable true that the majority of the new images now ordered by Tibetans for their rebuilt temples are sculpted by Manjoti Sakya, for he is well known among them and highly regarded as a sculptor. He says that they are by and large easy and pleasant to work with, though they are strict as regards the rectitude of iconographical detail (No doubt such strictness is a beneficial influence in preventing the degeneration of the art forms.)

According to Manjoti, his father, when asked to sculpt an image would go to a temple containing an image of the god that was requested and study that image, often taking sketches and notes. During the period of actual sculpting in wax, the image used as a model might be revisited and referred to serveral times. He also used books giving rules concerning the form and iconography of different deities; these books were in the possession of Sakya pandits, and Manjoti's father would go to the house of the pandit to consult the books and ask advice of the pandit himself.

Fig. 2 Many of these books were entirely literary, without designs of any kind; in addition there were books of sketches which could be consulted. Manjoti himself had such a book of drawings made for him about 15 years ago by a Tibetan artist, but he says that he looked through the book several times, memorized the details and no longer consults it (Fig. 2).

The rise of photography has considerable eased to flow of information to the casters, for now it is no longer necessary to visit a sculpture in order to find a model, for almost all of the deities and styles are represented photographically in art books available in the valley. Indeed many of the pieces now being made are copies of antique, and in many cases very famous designs that can be seen in the museums of the valley and in any book dealing with Nepalese art. Manjoti himself often works from a photograph; in many cases the person who commissions a statue will bring in a photograph of a painting or image of the deity concerned. He has also worked from original statues of a small size, usually enlarging them in the process. Once, when he was working on images of the four Dhyani Buddhas for Sigha stupa in Kathmandu, Ananda Muni, a famous Nepalese painter, came to stay at his house and offered advice on proportions and iconographical details. Again, Manjoti often works without a model of any kind, creating the form of the god from his knowledge of proportion and detail and from his own imagination.

He has been the beneficiary of a mild form of Royal patronage, for recently the palace has ordered several minor images to be cast, among them 80 lion's heads for the Royal Office in Singh Durbar. He is also, as was his father before him, the maker of all cast pots and utensils used by the Royal Palace. These orders are indirect, since the Palace contacts Cottage Industries, who in turn contact Manjoti; such orders are of course not to be compared with those which used to be issued from the Palaces of the Malla kings, but they are a significant Royal contribution to the artistic traditions of the valley.

Images produced by Manjoti and his family can be seen in various locations within the valley. His grandfather sculpted the garudas, lions, and horse-like mythical creatures which stand as guardians in the courtyard of Rudhra Barna Mahavihar in Oku Bahal itself. His father produced the images of Suddhodana and Maya Devi, the father and mother of Lord Buddha, which stand on either side of the main door of the Vihar temple, and also the large figure on a pedestal, allegedly that of Arjarnber Purus, the bodyguard of Lord Buddha in a previous lifetime,[8] which stands in the Vihar courtyard.

Manjoti himself sculpted the large image of Padmasambhava in the Karma Kagyupa gompa at Swayambhunath; it was cast in brass approximately 20 years ago on Tibetan order, with a small image and a painting used as models. His cousin, Kuber Singh Sakya, manufactured the main image in the same gompa; this figure is not cast, but rather manufactured from beaten copper pieces. Manjoti also cast the brass figure of Maitreya Buddha in Dharmachakra monastery on Saraswati hill near Swayambhunath, also on Tibetan border. One of Manjoti's largest pieces is the 6 foot, 6 inch high image of Lord Buddha, cast for a new temple in Lumbini, the birthplace of Lord Buddha. He also cast the copper images of the four Dhyani Buddhas (excluding Vairocana, the fifth), in Sighal stupa in Kathmandu. These figures, all approximately 18 inches high, were cast under the patronage of a rich Newari merchant about twenty years ago. He has also sculpted a large clay image in Badhang gompa in Helambu, and also cast images for the late King of Bhutan and for temples as far away as Switzerland.

It is hoped that Manjoti and Tej Joti are not the last of their family to take up the respected profession of image casting; Manjoti's oldest son, Ratna Joti, 17, is now in school, and he is also learning how to engrave a finished piece, a skill that is said to be valuable training for a sculptor. It is hoped that he will take up his father's work when he has finished his schooling, and yet another generation will be added to this respected line of family sculptors.

Bodhi Raj Sakya is one of the few sculptors in Patan whose work can be said to exhibit as much skill and grace as that of Manjoti Sakya. A hard-working and prolific sculptor, he is probably the most popular commercial sculptor and caster in Nepal.

Although Bodhi Raj inherited a family trade in sculpture, it is a tradition that preceeded him by only one generation. According to Bodhi Raj, his grandfather was a caster of pots and lotas, while his father, Punya Raj, was the first in the family line to make images. His father cast the extremely fine figures of Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and the two Arhants which adorn the door and door-surroundings of Rudhra Barna Mahavihar in Oku Bahal. Cast in solid brass, these statues were most likely created at about the turn of the century, as Bodhi Raj has said his father was quite young when they were done.

Bodhi Raj's father died at the age of 49 when Bodhi Raj was only two years old; (Bodhi Raj is now 51). Thus the casting tradition was not directly passed down the family line. Bodhi Raj learned casting from his brother, Siddhi Raj Sakya, who in turn learned from Manjoti. He also says that he is to a large degree, self-taught; it is said in Oku Bahal that when Bodhi Raj and his brother were both young fatherless children, they used to play in the street with left-over bits of wax and fashion small figures of gods.

Up until six years ago, Bodhi Raj and Siddhi Raj worked together. Then there was a quarrel, supposedly started because of Bodhi Raj's fondness for gambling, which resulted in Bodhi Raj leaving his father's house and moving his family to another. It was at this time that he and the family of Puspa Raj Sakya became excpecially close, for Puspa's family helped Bodhi Raj set up casting on his own, and ordered many statues from him for their shop. For several years after their split there was some acrimony between Bodhi Raj and Siddhi Raj, but recently there has been a warming of the relationship, and now Bodhi Raj often visits his brother's house when there is casting to be done and help is needed. Siddhi Raj is also an extremely skilled caster whose preference is small copper pieces done in a Tibetan style.

Bodhi Raj is now a very successful artist, His pieces are very popular and he seems to be financially well off; at the moment he is rebuilding his house, which adjoins the Vihar.

Although both Bodhi Raj and Manjoti are artists of the first rank, their work differs in several respects. Whereas Manjoti does not cast in copper, Bodhi Raj does cast in copper, but will not cast in bronze, maintaining that it is too difficult to engrave. Bodhi Raj also does all the work on an image himself, from fashioning the wax to the actual pouring of the metal although he does have assistance from his family members in all phases of the process.

While Manjoti does all of his work on private commission, in the traditional method of a patronage, Bodhi Raj does almost all of his work for curio shop businessmen. He has cast one piece for a temple, although it is a somewhat strange design for a Nepalese artist; it is a naturalistic figure of an Indian guru in a temple near Balaju gardens.

Since Bodhi Raj makes most of his statues again and again, he always makes a das, a clay or resinated wax mold, of his original of any design; from these das he can fashion additional wax images. Since Manjoti usually makes only one wax at a time, he only rarely fashions a das. Other than these differences, the actual methods of sculpting of the two artists are nearly the same; both occasionally use photographs or original models, and both occasionally work from their own knowledge and imagination.

At the moment, Bodhi Raj has about 20 to 25 molds for statues of medium (6 inches) to large size, and also several of smaller size; these are his inventory, and they are constantly being re-ordered by businessmen. Often these statues are copied, which creates ill feeling although Bodhi Raj says he doesn't much care since the copies are invariable of far inferior quality (which is generally true). It is customary for a successful caster to give unused molds to less successful casters, which of course creates a much better communal atmosphere than the practice of stealing designs.

Of this inventory in copper statues, the Cakra Samvara, which the authors feel to be one of the finest tantric images ever fashioned by a Nepalese sculptor, is the most popular. Originally sculpted six years ago from a much smaller piece that a customer wished to have copied, he has cast some 30 to 35 pieces in copper since that time.

The next most popular images in his inventory are those of his Bodhisattva series, all 16 inches, sculpted both from original models and from his knowledge. The Vajra Sattva whose manufacture we will detail later in this report is one of this series, which also includes Manjushri, Amitayus, crowned Akshobhya and green Tara. These pieces can be seen in brass in almost every curio shop on New Road in Kathmandu, although he rarely casts them in copper.

Perhaps Bodhi Raj's most impressive work to date is his Indra, a sculpture of marvellous fluidity, expression and grace. About 10 inches high, he usually casts this image in solid copper; it is a copy of an older piece of the same design from which Bodhi Raj worked directly. More will be said of all these pieces towards the end of this report.

At the time of this writing, Bodhi Raj is working on two tantric pieces which are astounding in size and complexity. One is a 36 inch image of Meg Samvara, or Yamantake, the wrathful form taken by the Bodhisattva Manjushri to slay the demon Yama. It is being sculpted from a photograph of an original piece approximately of the same size. The other is a 24 inch image of Hevajra, the tantric form of the Dhyani Buddha Akshobhya sculpted without a model. Both are now in wax form; the Yamantaka is to be cast in brass, the Hevajra in copper. Both have been ordered by a Newari curio shop owner, though to call these figures curios would be most inappropriate.

There is good reason to hope that the family tradition of casting will not end with Bodhi Raj. His oldest boy, now 17, is learning the art, and can always be seen in the workshop whenever there is casting to be done.

Fig. 3 Over the past fifteen months, the authors of this report have seen many images being sculpted and cast; we have chosen two images in particular, however, to follow in detail from the beginning of the sculpting process to the final finishing and engraving. The first of these is a sixteen inch image of the Dhyani Boddhisattva Vajra Sattva, worshipped by some sects of Mahayana Buddhism as Adi Buddha (primordial Being), and by others as a reflex form of the Dhyani Buddha Vairocana. Sculpted by Bodhi Raj Sakya, this figure is one of his series of Bodhisattva images, which are usually cast in brass; this particular image, however, was cast in copper. The second image whose manufacture we chose to follow is a 24 inch figure of Vajra Pani, a wrathful aspect of the Dhyani Boddhisattva of the same name, sculpted by Manjoti Sakya and cast in bronze by his brother Tej Joti Sakya (Fig. 3). In the following paragraphs we will concentrate on a detailed description of the sculpting, casting and finishing of the Vajra Sattva of Bodhi Raj; additional notes at the end of this section will detail any differences in the processes involved in the manufacture of the two images.

1. An Image is Cast.

All of the images made in Patan are manufactured by the 'cire perdu', or lost wax, system. Briefly explained, this process involves the sculpting of an image in wax identical to the final metal image. This wax image is then covered with clay, and if hollow, the interior is also covered with clay. When the clay has dried, then the wax.is melted and poured out of the clay mold through a hole (hence the name 'lost wax'), and the metal is poured into the space once occupied by the wax. When the metal has cooled, the mold is broken and the image emerges. The lost wax process produces a sculpture in which fine details are possible, and in which there are no seams (such as appear when casting molds are used). Of course, this process demands that every piece be made separately out of wax, covered with clay and then cast, so that even images of identical design must be made from separate waxes and molds. Thus true 'mass-production' is not possible, although, as will be seen in the following paragraphs, the process of sculpting the wax figure can be considerably quickened through the use of a 'das', or wax mold.

Since the image of Vajra Sattva had already been cast previously by Bodhi Raj, it was not necessary for him to sculpt the image from raw and unshaped pieces of wax. Once a statue has been cast, it is possible for the sculptor to make molds of clay or hard resinated wax ('das') from the completed sculpture or from the original wax model. From these molds, more wax statues are fashioned; such was the case with the Vajra Sattva.

In using the das, sheets of warm and pliable wax are placed in the molds and pressed, so that the wax takes the shape of the interior of the mold, and thus the shape of one piece (hands, face, clothing, etc.) of the original sculpture. These pieces are then fitted together and joined by heat to make the wax figure, which is basically an exact replica of the finished statue. The wax, like its metal counterpart, is hollow and of varying thickness, the thickness depending on the type of metal to be cast. Generally speaking, the wax for a brass statue does not need to be as thick as that for a copper statue, since brass is more durable and less malleable than copper, and thus less likely to break or bend whenever stress is applied. The Vajra Sattva image whose manufacture we followed was originally intended to be made in brass, and later the decision was made to have it cast in copper.

Since the wax, which was made for a brass casting, was thinner than it should have been for a durable copper casting, some problems appeared after the casting of the image had beeh completed. More mention of these problems will be made in the following paragraphs.

The tools needed for the making of the wax figure are few and rudimentary. A few steel tools similar to the chisels used by Newari woodcutters are used to scrape and smooth the wax model; similar tools made of bone are also used. A smooth stone slab is used for rolling and flattening the wax into pieces suitable for pressing into the molds. A bed of coals is kept in a bowl for heating the wax to the desired pliability. The wax itself is of a dark color, hard when dry and extremely viscous except when heated to a high temperature.

If the statue has been cast previously, then the pressing of the mold-pieces is not a particularly time-consuming affair, nor does it require any skill on the part of the sculptor. For this reason, many of the wax models made by the casters' workshops are not actually fashioned by the master sculptor himself, but are made by the men, usually relatives, who work in the shop with the master. This is largely true of most of the images seen in the curio shops around Kathmandu.

Fig. 4 |

Fig. 5 |

Fig. 6 |

Once the wax figure is completed, it is completely covered in clay to form the mold which will receive the molten metal when the statue is cast. This particular process is crucial, for it is the mold as well as the wax which will ultimately determine the quality of the casting. The clay is put on in several layers, anywhere from three to five layers being used depending on the care that is to be taken in producing the image. The first two layers are light applications of a very fine-grained grey clay, which is applied in a liquid state and then dried (Fig. 5). Care must be taken that these first applications of clay reach into every corner of the wax figure so that a tight fit is assured around the wax (Fig. 6). Nails are driven into the wax before the clay is applied to bond the clay to the wax and prevent distortion in the mold.

Fig. 7 |

Fig. 8 |

Fig. 9 |

The process of applying the various layers of clay is the most time consuming step in the entire casting procedure, often taking as long as two months. The caster is at the mercy of the weather during this time, since the clay must dry evenly in the sun to assure that the wax model is not distorted nor the clay cracked by uneven drying. Obviously, for this reason, certain seasons are considered more auspicious than others for the manufacture of a statue. The best season is from March to May, when the sun is strong and the rains have not yet come. It is not satisfactory to dry the clay mold before a fire, for fear of either prematurely melting the wax or cracking the mold.

When all the layers of clay have been completely dried, the wax is melted and poured from the mold; this wax will be re-used (Fig. 9). The mold is then left to sit for several days before casting, although the period between the melting of the wax and casting should not exceed one week, as the interior of the mold is then subject to deterioration.

Up until the time of casting, the process of preparing the final mold has taken from one and half months to approximately three and half months. In the case of the Vajra Sattva, the mold was ready to receive the metal approximately six weeks after the wax model had been begun. This was largely due to the fine hot weather experienced during the months of March and April, which allowed each layer to dry quickly and evenly.

The two months of preparation are to be consumated in only one day. Casting is the climax of the process of manufacturing a statue. In one afternoon, over one month of delicate labor will either be rewarded or wasted. And if the casting is successful, then another month of finishing work will lie ahead.

In the case of the Vajra Sattva, the afternoon of the casting was particularily suspenseful. As was mentioned earlier, the original wax was made for a brass statue. Furthermore, the wax had been made in one piece, rather than in two, as is usual when preparing a copper statue of such a large size. The decision to cast the piece in copper rather than brass was made after the wax figure had been surrounded by its clay cocoon, so that no alterations could be made in the wax. Bodhi Raj Sakya had never before attempted to cast such a large copper statue in one piece with so thin a wax.

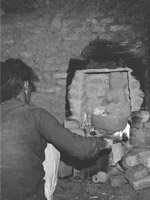

On the day of casting, two ovens are prepared and fired. The empty mold is placed in the first oven which is fed with wood fuel. Care must be taken that when the metal is poured the temperature of the mold and the metal are close enough to prevent the clay from cracking and to prevent the metal from cooling too quickly inside the mold.

Fig. 10 |

Fig. 11 |

Fig. 12 |

When the copper is completely ready for pouring, the mold is taken from the oven and laid against some supporting material, usually piled bricks, base upwards (Fig. 12). An inverted wax tripod attached to the original wax base of the figure forms a conduit for the metal once the wax has been melted and poured out. In the case of the Vajra Sattva, the mold was allowed to cool briefly before the crucible containing the copper was taken from its oven and the molten metal poured.

Fig. 13 |

Fig. 14 |

Fig. 15 |

Fig. 16 |

But the dull grey of the wax shall have been replaced by the iridescent rainbow hues of freshly cast copper. It is perhaps at this moment that the magic of the image cast in metal exerts its most powerful influence. The casting is perfect, without a flaw. Bodhi Raj, a few moments before nervous and worried, sits down with a smile to drink a cup of beverage brought by his wife. Soon the statue is completely clean, and is set, still resting on its inverted tripod, against a wall to be admired. The casting is finished.

After the Vajra Sattva had been cast by Bodhi Raj Sakya, it was taken to be smoothed and engraved by another artisan, Siddhi Raj Sakya (no relation to Bodhi Raj). The statue when it emerged from its clay mold was somewhat rough, due to the impression of the clay on the surface of the metal. Thus the first step in 'engraving', as the entire process of finishing a statue is called, is sanding. Only sandpaper is used, as steel wool is not suitable if the statue is to be gold-plated; the steel filings left behind would interfere with the process of gilding.

Sanding is only the first step in the case of a statue which has been well cast. When a statue is poorly cast or has some flaws which are not so serious as to justify melting down the metal, it is repaired, by welding other pieces of the same material to the affected areas.

When the sanding is completely finished, then the actual process of engraving begins. Using small chisels, the engraver redefines and sharpens the details built into the original work, and in some cases does original engraving work, chiseling scrolllike designs into clothing, etc. In some cases, he may inlay other metals into the surface of the statue. Several bronze statues have been made in Oku Bahal with three other metals (copper, brass and silver) inlaid into the clothing. In the case of the image of Vajra Sattva, the only work of this type that was done was the insertion of silver eyes.

It was during the process of engraving the Vajra Sattva that the hidden problems that were mentioned earlier began to appear. The unusual thinness of the original wax became a serious weakness. It is extremely difficult to do engraving work on a large and unwieldy statue without putting stress on exposed parts of the drapery and crown, and when this stress was applied the soft copper, cast too thin, began to give. Cracks appeared on the back and neck of the figure, the vajra at the top of the head broke off, and sections of the crown began to break and bend. Such problems can be repaired, but not without sacrificing some of the beauty and fineness of the piece as a whole, since wires of different metals once soldered on and applied, cannot be engraved for fear of again putting too much stress on the weakened area. Cracks through the main body of the statue cannot be repaired, and the only recourse in such cases is to leave them as they are or hope that if the statue is to be gilded the gold will fill the cracks. It is probable that these problems would not have appeared, had the statue been cast in brass as was originally intended or had the wax been of the correct thickness for a copper casting.

It must be said that the art of engraving has not maintained the same high standard over the years as that of sculpting. This is largely due to the viccissitudes of a mass market for cast images, all of which must be finished. A sculptor who intends to make a das of a sculpture and repeat the design will spend a great deal of time and effort on the original, knowing that the future popularity of the design will depend upon its aesthetic value. If the original is beautiful, then the sculptor will sell many; if not, the design will not be in demand. As a result, a commercial but skilled sculptor such as Bodhi Raj Sakya will take great care on any original piece he makes, for he knows his reward for a job well done will be orders for copies, which can be turned out by the use of das. In this way, the tourist market for images has, in a certain sense, kept the quality of sculpting high; unfortunately, it has not had the same effect on the craft of engraving, for which the Newari artists used to be so famed. Previously, images were produced singly, and of course were only produced for religious purposes; thus a great deal of work would go into both the sculpting, which was done without the use of das, and the engraving, with the engraver knowing fully well that the image on which he was working was unique, and would be set in a temple or on a house hold altar. Since there were far less statues being produced, it is likely that he had a great deal of time to spend on each image with which he worked. Now hundreds of images are being produced per month in such centres of casting as Oku Bahal, and each of these images, even a brass statue whose final cost might be only 50 Rupees, must be sanded and engraved. Such engraving is done on a daily wage basis, and, in order to keep the price of images as low as possible, the amount of time spent on engraving is kept to a minimum. As a result, most of the finishing work is hurried and sloppy, and the skills of most of the engravers has atrophied. The fine engraving work which used to be the trademark of a Nepalese bronze has now all but disappeared. It is hoped that the demand for expensive but finely finished pieces will grow, and thus create a need for fine engravers; there is no doubt that is such a demand existed, the latent talents of the Newari engravers would again reappear.

Although the procedures used by Bodhi Raj and Manjoti in the sculpting of the Vajra Sattva and the Vajra Pani were in most respects the same, there were certain differences, caused by the different metals used, and also the different ways in which the two men sculpt.

Since Bodhi Raj had already made several images of Vajra Sattva previous to the one written of above, and since he is a commercial caster who almost always makes an image with the intention of making others of the same design, he used a das when preparing the wax figure of Vajra Sattva. On the other hand, Manjoti, who is not a curio shop sculptor, did not have a das of the Vajra Pani, and the entire image had to be sculpted from raw wax. As a result the making of the wax was the most timeconsuming part of the whole casting procedure in the case of Vajra Pani, whereas, in the case of Bodhi Raj's Vajra Sattva, the wax was completed in very little time. It must be emphasized, of course, that although Bodhi Raj uses a das for statues he has cast previously, he is also a creative sculptor who is constantly adding to his list of original creations.

Other differences are accounted for by the differences in size and the metals used in manufacturing the two images. The Vajra Pani was cast in two pieces, base and figure, and in both cases, more than one conduit pipe was used to ease the flow of the metal into the mold. The actual figure of Vajra Pani was cast from the back, rather than from the feet, as is customary. Tej Joti had decided that the image would cast more perfectly if several conduits were used, and this was not possible if the figure were to be cast from the feet.

Since the Vajra Pani was cast in bronze and not in copper, a closed crucible was used to melt the metal. The oven in which the metal was melted was fed by charcoal, rather than coal, as coal is only necessary in copper casting, charcoal being used for both bronze and brass.

2. Tools, Materials and Metallurgy

Fig. 17 The tools required in sculpting and casting are relatively simple. All that is required for sculpting are a few bone implements for shaping and smoothing, a metal implement which is heated for shaping cooled wax, a smooth stone table for rolling and flattening the wax, and a clay pot for the charcoal fire which is used to heat and soften the wax (Fig. 17). Casting tools are also relatively simple, consisting largely of iron tongs of several sizes for grasping and pouring the molds and crucibles. Two ovens are used, one for heating the mold and one for melting the metals; the Indian mechanical bellows used to fan the flames is probably the most technologically advanced tool in any casting workshop; other than this item the tools have doubtless remained the same over the centuries. The crucibles are of two kinds; a closed crucible of clay for bronze or brass, and an open crucible of glazed clay for copper. The former is made by the casters themselves, while the latter is imported from India.

The wax used in modelling is a combination of bee's wax, ghee, and 'shilla' (Newari), a tree resin imported from India. The bee's wax is brought from Trisuli and Barabise with some coming from Pokhara. The combination of these ingredients varies with the season. Dark wax, used in the winter months, is a combination of 1 darne of bee's wax to 1 and 1/2 to 2 pou of shilla, with about 1/2 pou of ghee added, while light wax is a mixture of 2 - 3 pou of shilla to the same amount of bee's wax. Thus the light, or summer wax is stiffer and less likely to melt in the heat of the summer sun. The light wax generally replaces the winter wax in March, and it is used until October. The final wax, of either type, which is called 'shee' in Newari, costs about 65 rupees per darne. The casters mix it themselves. Wax that has been melted out of a mold is reused, with the ghee replaced.

The clay used in the first, or inner layers of the mold is grey and fine in texture, and is found in various places in the valley several feet beneath the topsoil; the casters purchase it from Jyapoo farmers. The outer layers of clay are of a less fine yellow soil mixed with paddy husks, which gives lighter weight and a rough texture.

Of the three metals usually used in casting , copper is the most difficult to melt and cast, and bronze is slightly more difficult than brass. All three are bought in the market in Kathmandu; the best copper is imported from India in sheets, as is the best brass; but with both these metals, scrap pieces, old wire and utensils are also melted down and used for casting; The best bronze is in the form of old plates and pots bought in the market. The prices for these metals at the time of this writing are as follows: brass 29 rupees per darne; bronze 45 rupees per darne; and copper 75 to 80 rupees per darne.

It is difficult to ascertain the melting points of these metals since we do not have the proper instruments. According to the casters, copper has the highest melting point; bronze, a combination of copper and tin, less than that of copper; and brass, a combination of copper and zinc, the lowest. When coal is used, the melting time for two darne of copper is about two hours, whereas if charcoal is used the melting time would be doubled. Brass and bronze both take about one hour for two darne to melt with cahrcoal as fuel.

Other metals are also occasionally cast in Oku Bahal, such as silver, 'white metal', and, very often, iron. Both 'white metal', alloy, and silver are easy to cast, but iron is very difficult. There is one image presently in Puspa Raj Sakya's shop that was cast solid with melted silver pieces which contains five kilograms of 85% pure silver; obviously, due to the expense, this is not often done.

As to their relative merits as materials, each metal has its own advantages and drawbacks. Copper is difficult to melt and cast, as well as being expensive, but is very easy to engrave, being soft and malleable, and is relatively easy to repair in cases of minor areas of miscasting. Another advantage of copper is that it is easy to gild. It is the only metal now gilded in Oku Bahal. Bronze, although it is a traditional metal, is rarely used because it is brittle and very difficult to engrave. Brass is the most frequently used metal because it is easy to cast and relatively easy to engrave (though not so easy as copper). Neither bronze nor brass is gilded in Oku Bahal, although the casters have said that it is possible to gild pure brass or bronze. In cases of minor mis-casting, both bronze and brass are more difficult to repair than copper.

It is not enough to base a case for the continuing excellence of Nepalese image casting on the mere fact that images are still being made. Obviously, if no talent for sculpture is shown in any of the images produced by the casters of Oku Bahal, then the art of casting in Nepal can indeed be declared dead.

Fortunately, talent in sculpture is not in short supply in Oku Bahal. Several of the casters who work there are creative artists of the first rank, as the accompanying photographs will certainly show.

In terms of style and tradition, the sculptors of Oku Bahal are not limited to one particular vision, as were their fore-fathers. They are influenced by styles long dead, as well as styles that began in the last two centuries. With the advent of photography and art books, the sculptors are able to peruse through images of sculptures that were manufactured during the Gupta period in India as well as those of 19th century Tibet; such access to so many images was of course denied to their ancestors. The result of this profusion of models is a corresponding profusion of styles, so that an approach from the point of view of art history is difficult. One caster in Oku Bahal has even made very beautiful brass copies of Gandhara images carved from stone.

Nevertheless, it is possible to see that each caster has his own particular preference in terms of style, and in each image sculpted, even if no model was used, the antecedents of the sculpture can be clearly seen. The following five examples, taken from the work of Bodhi Raj Sakya and Manjoti Sakya, will serve as an indication of the influence of previous styles and also as testimony of the sculpting skill of these two artists:

1. The Sighal Dhyani Buddhas of Manjoti Sakya.

These four images, of Amitabha, Akshobhya, Amoghasiddhi, and Ratnasambhava, are located in the four directional niches of Singhal stupa near Tahiti tole in Kathmandu. They were cast approximately 20 years ago on the order of a businessman of the Udas caste. About 18 inches high, they were cast in copper. The sculpting was done without a model, but as was mentioned earlier, Ananda Muni, a famous Nepalese painter, helped with iconographical details.

These images have stylistic precedents in Nepalese art. One image of Lord Buddha Sakyamuni in the Patan museum, dated fifteenth century,[9] is very close to Manjoti's image in style, although the face has a more chiselled and arch expression than the faces of the Sighal images, in which the expression is soft and muted. The greatest similarity is apparent in the sturdy build of the bodies and the monastic robes in which the images are clothed. This type of clothing is an indication of a direct influence from Tibetan styles. The Tibetan influence on Nepalese art has been strong and vital ever since the fall of the Indian traditions and the cultural exchange between Nepal and Tibet began; in fact, influence from Indian and Tibetan traditions can often be seen in Nepalese pieces which were manufactured at the same time. Thus there are several published examples of Nepalese bronze Buddha images made during the fifteenth century in which the clothing is soft and diaphanous, as is the case with Indian Gupta-period Buddha figures, and the right shoulder is left bare.[10] This contrasts quite sharply with the Tibetan tradition of clothing the figure of a Buddha in monastic robes which hide rather than emphasize the outlines of the body, and in which the right shoulder is always covered.

Whereas a direct influence from Indian art is no longer possible, as the art is dead, the Tibetan influence on the work of casters such as Manjoti is still very strong even today. Several of the artisans of Oku Bahal have had direct contact with Tibetan artists. Nati Kaji Sakya, for example, who fashions repousse calendars and plaques, went to Lhasa before the Chinese takeover and learned engraving and goldsmithing there. (Manjoti makes the bronze molds from which his plaques are beaten.) Although Manjoti himself has never been to Tibet, the Tibetan influence is obvious in his work. The book of drawings alluded to earlier, which he studied for iconographical details, was drawn by a Tibetan artist, and this surely influenced him. Many of his commissions come from refugee Tibetans, and, whenever they bring a model to follow, whether it be a painting, drawing, or image, it is also in the Tibetan idiom.

It must be emphasized, however, that Manjoti, like all fine artists, is not self-consciously aware of the forces which shape his style. When he was asked whether he preferred Tibetan or Nepalese style, he laughed and said, 'They are the same.' The exchanges over the centuries between these two great cultures lend more than a grain of truth to this statement.

Whatever the style, the image of a Buddha is central to Asian art. It is the ultimate artistic expression of the Buddhist religion; and as such, it has always fascinated Asian artists, whether they be Indian, Nepalese or Tibetan. The difference between a beautiful and successful image and one which fails is very slight, and can only be measured in slight alterations of stance, balance and expression. The Sighal images of Manjoti must be judged a success, for they well express the sublimity and peace which is the essence of Buddhism. In the opinion of the authors, the four images cast by Manjoti contrast favourably with the fifth, that of Vairocana, which was cast earlier by a different artist. The Vairocana figure is poorly modelled and seems somehow out of proportion, with too thin a neck and narrow shoulders. As so often happens with late period images of the Buddha, the smile is pinched and almost silly. In Manjoti's figures, on the other hand, the bodies are firm and graceful, leading the eyes upwards towards the face, on which is modelled the famous expression which is the goal of any Buddhist painter or sculptor, the smile of complete understanding.

2. Vajra Pani of Manjoti Sakya

This 24 inch figure was cast in bronze on commission from the authors. Manjoti had previously done one other figure of Vajra Pani, somewhat smaller, in brass; it was commissioned approximately ten years ago, on private order from a Newari man for his household order. This first image was sculpted with photos of a Tibetan thanka and his book of drawings as models; he did not, however, take a das of the first image, so the second was also sulpted from raw wax.

The Tibetan style in this image is obvious; the models used in sculpting it were Tibetan in origin, and the god himself, very popular with Tibetan Buddhists, is very rarely seen in Nepalese art. In the image itself, the Tibetan influence is manifested in the crown of skulls, ornaments, drapery, and the lunging movement of the body.

As in all images of wrathful deities, the goal of the artist is not to express subtlety and peace, but energy and action. Although in our opinion this is less difficult a task than the successful rendition of the smile of a Buddha, it is a task in which Manjoti has certainly succeeded. The face of the god is contorted and grimacing, as befits the great 'Wrathful Protector' Vajra Pani, and his body, squat and powerful, lunges forcefu lly to the right. One stylistic device seems to be entirely Manjoti's, as we have never before encountered it in images of this type, either Tibetan or Nepalese; that is the bumpy contours of the cheeks and nose of the god, which adds considerably to the ferocity of expression.

3. Vajra Sattva of Bodhi Raj Sakya

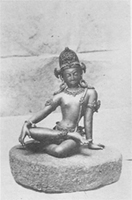

Fig. 17A Cast for the authors in copper, this figure is one of a series of similar 16 inch Bodhisattva images which form one of the most popular groups of Bodhi Raj's images (Fig. 17A).

Again, the Tibetan influence is strong in this figure. Early Nepalese Bodhisattva images are more compact and modelled than this image, with less emphasis on flowing drapery, although there is usually a great deal of fine engraving and finishing work.

Whether Tibetan or Nepalese in style, the figure is certainly one of the finest images of its kind ever produced by a Nepalese sculptor. It compares extremely favourably with images of the same god which can be seen in various temples in the valley, such as Swayambhunath and Sighal stupa.

The Sighal image, for instance, which sits at the top of a high pole facing the stupa on the side opposite the entrance, is somewhat less graceful than the Vajra Sattva of Bodhi Raj. Although it too shows Tibetan influence in the drapery and crown, the body is somewhat too squat and stiff to take full advantage of the gods asana, which Bodhi Raj has incorporated into a flowing, graceful flexion of the body. In Bodhi Raj's image, there is a pleasing combination of movement and quiescense which gives an impression of peace without any impression of stagnation. As in all of Bodhi Raj's images, the proportions are perfect.

4. Chakra Samvara of Bodhi Raj Sakya

Bodhi Raj originally made this image on the order of a Newari curio shop owner nine years ago. He worked with a small Tibetan statue as a model, and his original piece was a miniature of 6 inches. Later he enlarged the same design to 12 inches.

In terms of complexity, tantric pieces such as this image are the most challenging for a Buddhist sculptor. It is difficult to create a sense of grace or beauty in an image with such a profusion of arms and legs, and with such a wealth of mandatory iconographical symbolism and detail. In Oku Bahal, many armed tantric statues have been the speciality of a Jyapoo sculptor known as Kalu, who was discovered by a Sakya businessman when sculpting clay images, and was hired to make wax images which were then cast. Kalu's images, though done with a commendable ferocity of expression and energy, tend to be somewhat stiff and static. Each arm in these pieces is a duplicate of any other arm, and the limbs are placed in a fan-like arrangement with no variation in position. Bodhi Raj, on the other hand, sculpted his Samvara in a graceful supple pose, which gives the impression of dance-like movement. Each arm and hand is held in a different position, bending from elbow and wrist. The two embracing bodies sway to the left, while the heads of Samvara are slightly bent to the right. The entire impression is that of an image which was caught in the middle of a cosmic dance, and which at any moment might spring to life.

Again, this figure shows a strong Tibetan influence, although in tantric images such as this one the distinction between a purely Nepalese or purely Tibetan style is negligible.

5. Indra of Bodhi Raj Sakya

Fig. 18 Usually cast in solid copper, Bodhi Raj's 10 inch image of Indra, Lord of the gods, was first sculpted 3 to 4 years ago with an antique Nepalese image used as a model. He has stated that in sculpting it, he made various changes in the model's posture, face and crown (Fig. 18).

It is the opinion of the authors that this image is perhaps the finest piece created by a 20th century Nepalese sculptor; it is also our opinion that it is the finest image of Lord Indra that we have ever seen. It compares favourably with images of the same god that have been published in art books, of which there are many, since this god has always been a favourite subject for Nepalese sculptors. The statue which it most closely resembles is the 10 inch bronze image a photograph of which is published in Kramrisch's Art of Nepal.[11] There are differences between the two however; in the Kramrisch bronze, the head is bent downwards, as if in a pensive mood, and the legs are in the posture known as 'Lalitasana', the position of 'royal ease', with one leg tucked up as in the lotus position, and the other pendant. Bodhi Raj has sculpted his Indra with head held high and erect, and with the right foot resting on the left knee. The entire impression is one of slightly arrogant repose, as might well befit the 'Lord of the Gods'. It would not be fitting to suggest that the impression of haughtiness pervading Bodhi Raj's Indra is more fitting than the somewhat more reflective attitude seen in the Kramrisch bronze, for Indra is capable of many moods; but it is possible to make a qualitative distinction between the two pieces on other grounds. The antique piece has certain flaws which render it, though beautiful, somewhat less than perfect; the legs seem slightly short when judged against the length of the torso and arms. The feet are stiff and the ankles overly thick, and the pose suggests some tension and strain, as though effort was needed to keep the right leg raised and supporting the arm which rests on the right knee, which contradicts the desired impression of 'royal ease'. Bodhi Raj's figure, on the other hand, is convincingly effortless; no strain whatsoever is suggested in the positioning of the arms and legs; each limb supports another, and the entire figure is supported by the erect spine and straightened left arm. The modelling of the body is extraordinary; the detailed feet, tapering ankles, sculpted knees and limply hanging right hand suggest a knowledge of anatomy truely remarkable in an Asian religious sculptor. Not a single detail mars the overall impression of grace, balance and fluid repose with which this image is imbued.

There is of course no question of Tibetan influence in this statue, for whereas Indra has always been a popular subject for Nepalese artists, he is practically unknown to the Tibetans. Of all the gods of Asia, Indra is the most purely Nepalese in terms of religious art.

The art of casting in Nepal is now in a state of flux and transition. The casters who are working today belong to a crucial generation of Nepalese sculptors, for they live between a past that had not changed appreciably for several centuries and a future which may hold more change than even the most far sighted can predict. With the opening of the Kathmandu valley to tourism and the accompanying western ideas and values, all Nepalese are subject to influence which might tend to draw them away from the traditions of the past. Some observers have predicted that ancient skills will be lost in a rush towards the modern age; it is our opinion, however, that this will not be the case with the art of image casting. The Sakya craftsmen of Oku Bahal have already shown the flexibility and devotion to their art which has kept their skills alive over so many centuries, and which, in the midst of modernization, has brought about a profusion of talent so impressive as to warrant the term 'renaissance'. It is our opinion that the work of these sculptors is not only as good as that of artists in the past, but in many cases is better, and is certainly better than any sculpture done within the last century.

We would suggest to any art historians who would mourn the death of Nepalese art that before writing an obituary they should pay a visit to the sculptors of Oku Bahal.

FOOTNOTES

A. At almost the same time as this article was published in Contributions to Nepalese Studies, another article on the casting techniques of the sculptors of Oku/Uku Bahal, focussing on the great sculptor Jagat man Shakya, appeared in the third issue of the first volume of the newly founded journal Kailash: Marie-Laure de Labriffe, 1973, "Etude de la Fabrication d'une statue au Nepal" Kailash, vol. 1 number 3, pp 185-192.

1. Kramrisch, Stella, 1964, The Art of Nepal, New York: Asia House Gallery Publication, p. 49

2. Mehta, Rustam J., 1971, Masterpieces of Indian Bronzes and Metal Sculpture, Bombay: D. B. Taraporevala Sons and Co., Pty, Ltd., p. 20

3. Coomaraswamy, Ananda, Rupam, Vol 2, as quoted by Mehta, Rustam J., 1971, p. 23-24

4. Mehta, Rustam J., 1971, Masterpieces of Indian Bronzes and Metal Sculpture, Bombay: D. B. Taraporevala Sons and Co., Pty, Ltd., p. 32.

5. Mehta, Rustam J., 1971, Masterpieces of Indian Bronzes and Metal Sculpture, Bombay: D. B. Taraporevala Sons and Co., Pty, Ltd., p. 32.

6. Nepali, Gopal Singh, 1965, The Newars, Bombay: United Asia Publications, p. 77.

7. This estimate is that of Puspa Raj Sakya of Oku Bahal. Most of the information contained in this part of the report comes from him.

8. This legendary figure, as explained by Manjoti Sakya, is presumably a character from the 'Jataka Tales'.

9. Photograph published in Waldschmidt, Ernst and Rose Lenore, 1969, Nepal. Art Treasures from the Himalayas, Calcutta, Oxford and IBH Publishing Co., Plate 37.

10. Kramrisch, 1964, The Art of Nepal, New York: Asia House Gallery Publication, p. 85.

11. Kramrisch, 1964, The Art of Nepal, New York: Asia House Gallery Publication, p. 67.

Articles by Ian Alsop

asianart.com | articles