|

In this essay I propose to address two major subjects:

[a] Husain's imaginative "deconstruction" of modernity as it

manifests itself through European interventions in India--my examples

will be Husain's treatment of the railway (introduced in during the colonial

period), some of his "The Raj" paintings, and his depiction

of the missionary nun Mother Teresa; and [b] Husain's habit of forcing

an encounter between elements of postmodernity and corresponding features

of Indian culture. As we will see, in both these cases Husain's sense

of "transcendental" or augmented nationalism determines the

case in India's favour. Let me start with the first theme. A case in point

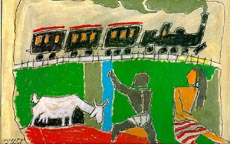

could be made by analysing Husain's oil crayon drawing "Apu and the

Train" inspired by Satyajit Ray's first major cinematic work, Pather

Panchali (1955). We will see how, among other compositional innovations,

Husain adopts a child's eye perspective to produce a mocking image of

the effect of western modernity in India. "Apu and the Train"

illustrates (if that is what it does) the memorable scene in Ray's movie

where little Apu and his sister Durga watch with fascination as the first

railway train they have seen passes by. For viewers of Ray's film, which

has often been described as a "neo-realist" work (Dutta 55),

the train is an ominous and frightening symbol of modern machinery that

intrudes upon the fragile pastoral scenery of the little protagonist's

childhood. In Apu's youthful mind, however, the train evokes wonder and

amazement, the vaguely humanistic dreams of an indistinctly imagined future

of immense possibilities and boundless distances. In the movie, as in

the novel by Bibhutibhushan Banerjee upon which it is based, the train

is a powerful agent of modernity that is inevitably seen as trampling

underfoot--if not actually decimating--the supposedly vulnerable and defenceless

social fabric of pre-industrial rural India. In Husain's picture some

of the tragic feeling for the young protagonist's subsequent loss of childhood

and innocence is retained while a graphic separation is effected between

the precariousness of individual childhood and the sturdiness of

the larger-than-individual native topography of rural India. The

train may signify Apu's eventual loss of innocence, but it is not allowed

to assume any larger proportion, nor permitted to present itself as any

kind of significant menace.

How does Husain achieve this effect? He does

it by employing a number of spatial and perspective-manipulating strategies,

some of which are decidedly filmic--although not derived from Ray's

particular movie that forms the narrative subtext for the painting,

one that Husain creatively "misreads." In his movie Ray conveys

much of his message by having the camera focus upon the face of Apu,

particularly his wide, wonderstruck, dreamy eyes.

10 Husain presents

Apu with his back to us--he stands in front of us in the centre foreground,

his face away from us as he looks at the passing train in the background,

the upper half of the picture. On the other hand, his sister, Durga,

faces us, although the oval of her bright ochre face, traditionally

the colour of Indian soil, is featureless.

Husain presents his picture within two elongated

rectangles one sitting above the other, the lower one being the foreground

containing the lush topography of Bengal as well as the two human characters

and a roguish white goat. There is much colour and vitality in this foreground

which has two deep green rectangular patches occupying most of the space.

One green patch comprises the entire right lower half of the picture, the

other green square is on the left nearly entirely framing the white goat.

Between the two green rectangles--clearly suggesting the dynamic vigour

of the fertile soil of eastern India--are two vertical strips extending

from the near edge of the picture to the top of the lower rectangle. One

strip is painted bright blue, surely a narrow but significant stream that

waters the land and nurtures human beings, animals and vegetation. The

other strip is a footpath between the fields, suggesting both community

and history.

The narrow and long rectangle that comprises

the top half of the picture shows us the train. Husain has drained out

all colour from this half of his picture. The foreground, as I have noted,

has the vivid blue of water, the luxuriant green of the fields, the orange-ochre

of the soil, the bright red stripes of Durga's saree, the white of Apu's

loin cloth, and the sturdy-looking white goat. In the upper half of the

picture the sky is painted a drab smoky haze, against which a miniature

two-dimensional train with three tiny black coaches pulled by a black steam

engine are presented as if drawn by a child in a kindergarten classroom.

Husain critiques Ray's simple realism, and using an improbable cartoon

technique juxtaposes the mature, solid yet unostentatious craftsmanship

of the foreground against the successfully imitated child's elementary

drawing of a toy train across the top half of the picture. By means of

this compositional innovation Husain situates his somewhat essentialist

and anti-historicist reading of the role of modernity in India directly

beside the realist Ray's much acclaimed "integrity in the handling

of social history" (Barnouw and Krishnaswamy 236).

Railway was introduced into India by the British

government in the middle of the nineteenth century. By the early part of

this century it had become the most pervasive mode of transportation in

India, giving the country one of the largest networks of passenger and

goods movement systems in the world. Probably more people travel by train

in India each day than any where else on earth. But the great mechanical

horse of modern technology has been reduced by Husain to an ineffectual

two-dimensional cut-out toy. Drawn as if by a child, the engine and the

coaches have been first outlined in the most elementary fashion and then

filled in inexpertly with black crayon. While the train and the engine

are coloured black, the overall lack of depth denies it any power, sinister

or otherwise. The engine belches dirty green smoke against the dull background;

and three puffs, again drawn in an unsure hand, create a questionable banner

of sorts across the top right of the drawing. The puff over the engine,

on the right, is the largest; the two behind it--occupying roughly the

top centre of the picture--are much smaller, the third one being the smallest.

This creates a wedge-shaped patch of dull grey-green across the top right

of the upper rectangle, wide on the right and narrow on the left. As one

glances at the bottom edge of the picture one cannot help noticing that

Husain has drawn a corresponding (but also contrasting) wedge of bright

red across the forepart of the foreground. The red wedge is wider on the

left, and it narrows towards the right. As Apu waves energetically at the

distant train, he stands ankle-deep in this splash of invigorating red,

perhaps the substance of life itself.

I have spoken repeatedly of the top and bottom

rectangles; and by this division Husain, I think, creates more than just

structural patterning. The artist has, indeed, sharply outlined the two

rectangles, the top one sitting a little distance beyond the top edge of

the one at the bottom. Husain seems to achieve several different effects

by drawing the outlines of the two rectangles. The most obvious is that

it allows him to position his composition away from the four edges of the

paper thereby leaving a narrow band of unused space all around the picture.

(Even his signature is placed outside this outlined area.) The effect is

strikingly similar to the experience of looking at a single frame in a

strip of movie film: the picture itself surrounded by blank celluloid space

at the edges. By leaving a gap between the lower and upper rectangles,

a gully of sorts running horizontally across the middle of the picture,

Husain further emphasizes the distance between Apu's native world and the

shadow world of imported and imposed modernity and machine power.

Husain heightens the contrast by yet another

clever device. The top border of the lower rectangle and the bottom border

of the upper rectangle are linked by a series of unequally spaced and unsteadily

drawn short vertical sticks. These attempt to transform the two lines at

the middle of the picture into a child's representation of a set of railway

tracks, the 'sticks' being the ties between the parallel rails. But instead

of creating a link between the two worlds, those of Apu and the train,

the chasm between the two rails is made more gaping, virtually absolute,

by the use of white crayon fill-in between the ties. The two-dimensional

train, of course, rides the further rail in a fashion entirely improbable

to the adult eye. Thus the engine and the coaches sit just above the white

gully between the two rectangles, beyond an unbridgeable gap. Even if the

railway track with its stick-like ties attempts to form a clearly untenable

link between the lower an the upper halves of the picture, the train itself

is contained entirely within the spectral, colourless upper rectangle,

a space--rather a single plane--apart from the real vital world depicted

in the foreground. In the physical world inhabited by Durga and Apu, the

perspective from which people and objects are presented is reliable and

their arrangement is believable. Thus Durga's hair covers her left shoulder,

her right arm lies across her lap, and even the horns on the goat are drawn

to suggest an appropriate distance between them.

If the foreground is filled with the bright colours

of a sunny day, the train is trapped within a shadowless enclosure which

depicts neither night nor day, but a colourless, greyish yellow gloom.

Still, it is not night yet, although artificial interior light dully fills

the frames of the empty coach windows. Not a single passenger travels by

this train. The only colour to be found in the top frame of this picture

is in the short, bold single horizontal stroke of red crayon Husain has

placed just above the roof of each of the three coaches. The effect is

almost that of chastisement. The vivid red lines draw our attention back

to red band across the bottom of the picture, the vital ground that sustains

Apu, and seem to press down upon the train brining to bear upon it a downward

pressure almost capable of collapsing its flimsy man-made structure.

Of course, one might be tempted to characterize

Husain's anti-modern, anti-industrial deconstruction of Ray's movie--or

at least of a pivotal scene in it--as merely escapist fantasy, as unjustifiably

romantic pastoralism. But one would not be correct in making that easy

judgment. The sturdy, comic goat, so vitally present in the picture, allows

for a playful self-awareness that counters any suggestion of escapism.

The goat, incongruous in the overall serious and even didactic tone of

the picture, is also entirely congruous in a depiction of rural life in

India. It provides a focus for the inherent and desirable collapse of rationality

that Husain appears to support--especially in the context of a country

that baffles modern notions of history, a notion that has the idea of "progress"

as its cornerstone. In other words, Husain creatively misreads colonialist

and bourgeois historiography and shows the imported and imposed modernity

to have been subsumed by a potent India. The imported notion of nationalism

has been, I propose, "augmented"--augmented by its incorporation

into a local or pre-colonial (therefore pre-modern) mode of valuation.

IV

Socio-economic change, including industrialization,

was not the only aspect of colonialism to affect India. Christian missions

and missionaries, too, were active participants the imperial agenda. Although

the activities of the Church have extended all the way from undeniably

pernicious to the admirably beneficial--from coercive mass conversion to

the establishment of educational, medical and similar modernizing institutions--even

these latter activities can be held up for scrutiny. Husain seems to have

done precisely that in a series of paintings about Mother Teresa, the celebrated

"Saint of Calcutta." While the painter's admiration for the missionary

worker is obviously very high, at times he appears to presents her in a

manner that problematizes the subject in an unusual way. The series presents

Mother Teresa as having been absorbed into the city (and the country) she

has adopted as her place of work and as being deprived of her identity.

I think Husain questions the odd way in which the tag "Mother Teresa

of Calcutta" operates in the minds of people, especially those who

live outside India. If anything, the words tend to suggest the opposite

of what they seem to say. The popular understanding of the words suggest

that Mother Teresa is not of Calcutta; rather the city is hers, or that

the city has gained prominence and dignity through its association with

her. In this reading the city has been adopted by the missionary.

Irrespective of the good Mother Teresa does

to some people in India, the way the signification of her naming works

in the popular mind makes little sense. (One curious result of the nomination

is the nearly universal ignorance of the fact that Missionaries of Charity,

the Order founded by Mother Teresa, provides service to destitute people

in nearly one hundred countries--including virtually all nations of

the First World.) It can quite reasonably be assumed that she has been

transformed by the city, by the country, by its Gandhian tradition,

and so forth. Before she turned to her charitable work, Mother Teresa

taught school in India for many years; in this role she was no different

from many other unremarkable European teachers in Catholic mission schools

in Asia or Africa. Her sudden moment of change--she has described it

as "a call within a call"--came in 1946, at the height of

the movement for India's independence--a year before the country attained

its freedom. It is hard not to see a Gandhian influence in this conversion

which made her an active participant in the new spiritual

adventure on which the soon-to-be-liberated India was embarking. 11

Husain, appropriately enough for a painter, seems, primarily interested

in the way the signs--linguistic, sartorial, visual, and so on--work

in this case. To right the odd linguistic signification we must be willing

to read the phrase "of Calcutta" to mean "Mother Teresa

belongs to Calcutta (and to India)." One suspects that Mother Teresa

is not likely to question the appropriateness of this viewpoint. But

irrespective of her personal opinion, the public working of the sign

suggests the opposite. In that popular version she is seen as bringing

an impossible ray of hope into an entirely hopeless city. But as anyone

who is familiar with Calcutta knows, it is a place of incredible vitality

and energy; of much human suffering no doubt, but also of immense evidence

of human dignity and pride. Also, its history is inextricably linked

in the minds of Bengalis with the name of Rani [not a title] Rasmoni

(1793-1861), the pious lady whose charitable work is the stuff of the

city's legends. Moreover, to this list one might add the positive cultural

and artistic life that Calcutta makes possible for imaginative persons.

For Husain and for many million others in India, it is a metropolitan

place.

If the linguistic tag "Mother Teresa of Calcutta"

creates the wrong kind of connotation, so does the visual image suggested

by her blue-bordered white sari. Here, too, we see the firm cultural mooring

of the sign has somehow been destabilized to the point where the sari--now

neither Bengali or Indian--becomes the European nun's symbol. Ironically,

then, the indigenous sign appears to get validated by its use by an alien,

and also seems to achieve a new and augmented power of signification.

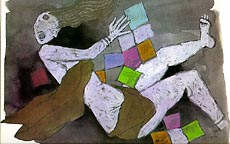

In Husain's's paintings Mother Teresa is always represented by her sari--by

a sinuous blue line at the edge of white space. It defines the outline

of her face and covers her head, but the head and the face are always

a featureless dark unilluminated area on the canvas. Husain overwrites

her individual identity with the help of her most prominent visible sign,

the sari she wears; and repositions the sign at once in its proper cultural

space by the erasing of the non-native owner's identifying features. The

darkened face of the Nobel-Prize winning social worker can be suggestive

of much: it can be the negation of ego that must surely be an attribute

of this profoundly selfless person; but it can also be indicative of Husain's

intention to avoid easy sentimentality. Cannot some acts of utter self-sacrifice

be hubristic? Why not? On basis of what foundational argument can one

assert that noble human deeds may not be results of obscure desires? (Later

in this paper, I will return to this issue--the obscure nature of desire.)

In a number of Husain's "Mother Teresa" series, we see the missionary

nun's arms extended towards a dark naked child, but as we gaze at the

dark space on the canvas that is the benefactor's face, we cannot but

wonder if the child is making an entirely beneficial transition.

Still, our reading of the "Mother Teresa"

paintings need not be unambiguously negative. Perhaps the nun's dark

face shows that she is now an Indian, a dark person, rather than a European

embracing exile in India. Perhaps, it is she who has been accepted,

embraced and validated--by India; and she is no longer a foreigner,

a white person. Such a reading is consistent with the fact that we are

looking at the situation through an Indian painter's eye rather than,

say, through the viewfinder of CNN's news camera. In such a reading

Mother Teresa is not degraded--at least no more than the numerous other

extra-ordinary people who inhabit India: the sages, the philosophers,

the saints, the poets, the lovers, and truly noble. That such people,

innumerable such people, still live in India is no mere legend. It seems,

then, the sari--restored to its appropriate Indian-ness--can add significance

to Mother Teresa instead of suggesting the opposite. One could also

argue that it is the sari, the symbol of Indian motherhood, that allows

the European nun to wear her title with justification.

Now, it is entirely right that the orphaned dark child should seek refuge

in the arms of this sari-clad, dark skinned mother of the poor and the

helpless. 12

|