Tamar Victoria Scoggin, M.A., M.S.

Waves on the Turquoise Lake: Contemporary Expressions of Tibetan Art - Lisa Tamiris Becker

Seeing Into Being: The Waves on the Turquoise Lake Artists' and Scholars' Symposium - Carole McGranahan and Losang Gyatso

Acknowledgements | Biographies

Waves on the Turquoise Lake main exhibition

|

|

| It has been a great honor to co-curate Waves on the Turquoise Lake: Contemporary Expressions of Tibetan Art. I could not have contributed to this exhibition without the help and inspiration of many people. I particularly want to acknowledge my colleagues at Mechak Center for Contemporary Tibetan Art, directors Losang Gyatso and Dr. Carole McGranahan, and my fellow curator and director of the CU Art Museum, Lisa Tamiris Becker. If Carole had not introduced me to Gyatso, I would still today be wondering why I became so intrigued with a small community of “modern” Tibetan artists in India in 1999. If Lisa had not taken an immediate interest in the idea of Waves in November 2005, this first and much-needed major museum exhibition of contemporary Tibetan art could not have come into being, but would still be awaiting incarnation. |

| Waves on

the Turquoise Lake: Contemporary Expressions of Tibetan Art inspired collaboration

in unprecedented ways. Art-works from Tibet hung in the same gallery as

those from Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Australia, India, and the United

States. Mechak and the CU Art Museum, two organizations in Boulder, Colorado,

compiled resources, connections, and know-how to bring a world-class exhibition

and artists’ symposium to their home. As a major museum exhibition,

Waves itself was a uniquely interdisciplinary presentation, curated by a

curator of contemporary art, art historian, and artist, Lisa Tamiris Becker,

and an anthropologically trained curator, me.

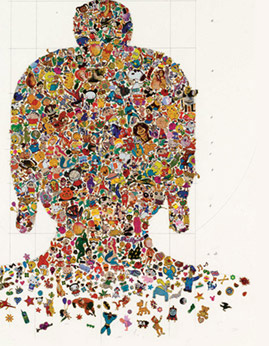

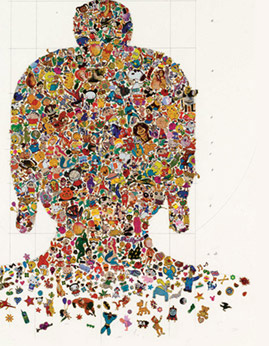

For the past seven years I have conducted research on the contemporary art movement in Tibetan communities around the world and in Tibet itself, mainly in the historical and current capital city, Lhasa. Studying an art movement through an anthropological lens, I have conducted fieldwork by meeting artists in their communities of creation, visiting them in their studios, “deep hanging out” with them in the restaurants, tea houses, and galleries that form their daily landscape and inspire their work. Seeking insight into their art, I have formally interviewed artists, asking such question as why they work with certain materials; why they choose to illustrate a concept in a certain way; what other artists, art movements, and elements of visual culture influence and inspire them. Most times, however, the best form of insight comes when we are simply chatting while touring studios and galleries, or collecting our thoughts over a cup of tea or a meal. When I cannot meet personally with artists, I have communicated with them by phone, e-mail, and Web networking. This first-hand way of working with the artists infused Waves with a most subtle, meaningful form of collaboration. Especially through the interpretive wall text that accompanied the artworks while on exhibition for Waves, I tried to evoke the visceral moment of insight I experienced while talking to artists in such places like London, Dharamsala, Lhasa, and Boulder. As you will read in this essay, such moments of transformative insight are as much about the curatorial process as the artistic one. Therefore, I offer my sincere thanks to all the artists I have interacted with over the years and with whom I have worked, most recently in making Waves. When Kesang Lamdark sent sketches for a proposed site-specific installation at the CU Art Museum for Waves, I was intrigued by his creative, if slightly unorthodox use of materials: perforated beer cans, scratched, broken glass surfaces, and light sources that glowed with postindustrial fluorescence and throbbing intensity, or snapped and flared like the tantric heat one often sees emanating from wrathful Buddhist deities in traditional Tibetan art. Having had this initial sensory impression of his work, I was curious to discover the conceptual underpinnings of it: its meanings, questions, and influences. By e-mail he told me that as a Tibetan raised in Switzerland, he wanted to explore the hybridity of his identity from the distinct subject position of someone both included and excluded in apprehending cultural reality; his installation Warhol of Tibet (2006) was made with this aim in mind. In its execution, Kesang was primarily inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s Étant donnés, which he had seen once at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Knowing this, I wrote in the wall text that accompanied this work: Kesang Lamdark invites the viewer to look inside the cans suspended on the glass wall, to witness his secret world—a world where Tibet is dreamt about and imagined from creative exile in Switzerland. The composition of this site-specific installation is inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s final work, Étant donnés, in which viewers are invited to peek through a crack in a door to view the image beyond. In Kesang Lamdark’s installation, the images beyond are mainly inspired by photographs taken during a trip to Tibet in 2004. He used these as stencils for the images that he pierced at the bottom of each can. As in Duchamp’s piece, the images of Warhol in Tibet are illuminated as if through the viewer’s gaze. In a final act of simulation, Kesang and the photographer Børgen Herzog photographed the illuminated images and reproduced them as accompanying C-prints. I first encountered Gonkar Gyatso’s work in Dharamsala, India in 1999. At the time I was a college student making my first foray into research on contemporary Tibetan art. For documentation, I photographed his elegant minimalist paintings, which I found hanging nondescriptly in cultural centers and hotels around town. When I finally met Gonkar in person at his gallery, the Sweet Tea House, in London in December 2004, I discovered that he had long since moved away from painting and was in the midst of exploring the aesthetics and conceptual resonance of text as art: hand-writing quotations from various Tibetan, Chinese, and English sources to compose the myriad iconic forms of Buddha. He was also starting a new project, in which, instead of using text as the uncanny vehicle and medium of his artworks, he was compiling the form of Buddha from popular-culture stickers: Pokemon, Simpsons, Japanese anime, Disney, and the like. These new works were visually complex and engrossing, and reflected Gonkar’s sophisticated embrace of avant-garde and Pop art, with a nod toward cultural commentary from a distinctly Tibetan point of view. He was able to address his muse—the figure of the earth-witnessing Buddha—in a ground-breaking way. These text and sticker pieces were featured in Mechak’s first exhibition, Old Soul, New Art: The Works of Three Contemporary Tibetan Artists, which traveled to New York City and Washington, D.C. in 2005. For a guide to the exhibition, I interviewed Gonkar, and asked about the sticker pieces: “Going to the studio became so heavy,” he says. “I felt so pressured to produce work. With these pieces, I made them on my kitchen table, with the television going and my daughter talking to friends on the phone.”“The Buddha image had become too heavy,” Gonkar continued, “but I still needed to explore what I could do with it. As I found myself in this new project, I realized that my muse, the Buddha, was a way of addressing my identity. Because of my upbringing, I never got to fully understand the heavy religious implications behind drawing the Buddha. I had some traditional thangka training when I first came into exile and lived in Dharamsala, but that is only introductory knowledge. So I figured, I would take what I know of Buddhism, and compare it with what I know about Western culture—the many interpretations Buddhism has gone through depending on fashion and trends.” He especially alluded to the current connection between people’s preoccupation with physical and mental health and Buddhist philosophy and practice. “When did Tibetans become experts in diet and exercise?” Gonkar asks, laughing.[1] Another artist whose work I first saw in Dharamsala in 1999 is Karma Phuntsok, who now lives and works in Kyogle, Australia. Along with Gonkar, Karma was one of the first artists to exhibit contemporary work in this community. Unfortunately, I had returned to Dharamsala from Tibet just after Karma’s exhibition, Continuum, closed, but echoes of his work were everywhere: postcards and catalogues were sold in stores, and I was able to catch a glimpse of some paintings that were kept at the Amnye Machen Institute, a cultural organization dedicated to developing research of contemporary Tibetan culture. I was magnetized by Karma’s work, and at the time was quick to compare the surreal quality of his paintings to the legacy of Salvador Dalí. Now that I have worked with Karma in Old Soul, New Art, I see his work in a broader context, both autonomous and reflective of his own life story and personal vision. It is striking to see how the place where Karma has chosen to live and work creatively, Australia, has threaded its way into his work visually and conceptually; I was thrilled to include a wonderful example of this influence in Waves, in the painting Vajra (2000). Living and working in Australia has inspired Karma to experiment with the fusion of Tibetan thangka painting and Central Desert Aboriginal painting. “My dotting lineage comes from Clifford Possum, an Aboriginal artist from the Central Desert,” he explains. “I was introduced to Clifford’s work through Tim Johnson,” a Sydney artist with whom Karma has also collaborated with artistically. A founder of the Papunya group of painters, Clifford Possum Tjapaljarri was renowned for “his brilliant manipulation of three-dimensional space,” with dotting used to depict the topography of the Central Desert country. Vajra is an intriguing example of how Karma appropriates the aesthetic innovations of Aboriginal fine art to recontextualize the visual legacy of classical Buddhist art. Vajra goes even further, to suggest a sense of surreal space in a Buddhaesque shape beyond the circular motions of the painted dots and double vajras, metal implements representing the hardness and clarity of a diamond. In summer 2006 I returned to Dharamsala for the first time since my 1999 trip, when I had discovered the contemporary art movement through artists such as Gonkar and Karma. Upon my return I met another artist whom I had known seven years before, Sodhon, as well as two others who became featured artists in the exhibition, Samchung and Namgyal Dorjee. When I first encountered Sodhon’s work in 1999, he was concentrating on portraits emphasizing ethnographic depictions of Tibetan dress and customs, as well as landscapes that celebrated the beauty, magnitude, and variety of the Tibetan environment, from verdant eastern grasslands to the high-altitude dry plateau. When I visited his studio again one afternoon, seven years later, as a curtain of pre-monsoon rain droned outside, I found that his work had changed dramatically. In the painting, Dharma Song (2005), the almost Cubist effect Sodhon employs in the composition of this piece is a style that was inspired when Sodhon made his first trip to New York City in 2003—amidst world-class museums, galleries, and artists, Sodhon experienced a paradigm shift into figurative abstraction and experimental color palettes. I also had occasion to hunker down in the studios of Samchung and Namgyal Dorjee to wait out spectacular rainstorms while viewing and discussing their art. Samchung is an incredibly prolific, eclectic artist; his stronger, more focused pieces are those that illustrate his memories of growing up in Tibet. Of Namgyal Dorjee’s work, a small, rolled-up painting on buckram cloth called Woman spoke to me more tellingly than the Photorealist paintings of chortens, temples, lamas, or mountainscapes on view in his studio. Namgyal Dorjee spoke of his desire to paint in a more imaginative way, to respond to his dreams and visions. Woman was a work created in response to this inclination; I was happy to represent this less-explored, more soulful side of his work in Waves. Beyond studios in Switzerland, London, Australia, and India, I have also encountered the contemporary Tibetan art movement right in my home state of Colorado, and the local fieldwork and studio visits there are just as insightful and inspiring. In Tenzing Rigdol’s loft apartment above the streets of downtown Denver, the artist explained to me his interest in fusing Tibetan and Western philosophy in his artworks, where the views of Nietzsche and Nagarjuna on the nature of existence intersect and diverge in a visual imprint. Fusion: Bud-dha-tara engages with concepts of hybridity, gender, tradition and modernity, construction and deconstruction. “Traditionally,” I wrote,`Tibetan paintings—whether religious or folk in nature—are not complete untilthe sketch lines upon form and composition are painted over, the process of artistic composition lost. In Fusion: Bud-dha-tara, both the lines and the forms are left together in the final composition. The figures of Buddha and Tara, male and female deities of compassion and enlightenment in Tibetan Buddhism, are fused with staccato placements of geometrical lines, colors, and texts, so that the representation of these traditional deities is contemporized through their aesthetic deconstruction. The works of Losang Gyatso featured in Waves also demand

an understanding of deeper concepts, philosophies, parables, and cultural

worldviews, while at the same time they simply resonate visually in vivid

color, movement, and presence. It is always a joy to be shown Gyatso’s

newest painting, because I know that I can not only expect a bold yet

inviting visual presentation, but will also learn something new such as

the intricacies of Tibetan folk tradition, or a grand parable taken from

historical or archaeological accounts of Tibet. An accomplished actor

and writer, Gyatso is extremely eloquent; he coauthored the wall text

that accompanied his works in Waves with me, and his words were the initial

vehicle. At the artists’ symposium that accompanied the Waves exhibition,

Gyatso told the story of Virupa (Birwapa), who laid siege to a village

during a drinking binge, as illustrated in his painting Securing the Shadow,

Stilling the Sun (Homage to Virupa) (2004). With the lights dimmed in

the auditorium, Gyatso told the story in dramatic and comedic vignettes,

treating the audience to projected details of the painting that depicted

elements of the tale. His storytelling was mesmerizing, and the overall

presentation magical. A glimpse of this is captured in the wall text for

Securing the Shadow, Stilling the Sun: Of all the studios of contemporary Tibetan artists I have visited in person or virtually, none were more important to Waves on the Turquoise Lake than those of the artists in Lhasa. Artworks from Lhasa completed the exhibition and fulfilled its goal to present the first comprehensive exhibition of contemporary Tibetan art. I first became aware of the strong, exquisite artworks of Lhasa artists when I visited the Gedun Chophel Artist Guild in 2005. Located at the northeast corner of the Barkor circumambulation route around the Jokhang temple, in the heart of Lhasa, this gallery is the brainchild of Tibetan and Chinese artists who united to form a guild to present fine contemporary art in a sea of tourist art and commodified culture. In this gallery I first saw the works of Gade Jhamsang, Dedron, Kaltse, Shelka, Nortse, Tsewang Tashi, Tsering Nyandak, and Benchung. Upon my return to Lhasa in 2006, I was also introduced to Migmar Wangdu, from the Shunue Dame Artist Guild, whose members were once students of many of the aforementioned artists and therefore represented the next wave of contemporary art in Lhasa. In summer 2005 I spent a little more than a month in Lhasa. While I was there Nortse asked me to curate an exhibition of his that featured a series of works he was ready to move away from: dark, brooding paintings that affected the smoked, broken appearance of wall murals in older Tibetan Buddhist temples. Nortse told me he was interested in experimenting with three-dimensional materials, with a conceptual aim toward environmentalist art and environmental consciousness. When I returned to Lhasa the following summer, I found that he had indeed shifted his work dramatically, exploring and executing artworks with a nod toward the Ready-made in arrangements of chopsticks, baby-bottle nipples, buttons, and broken globes. He was also exploring three-dimensional collages and the effect of simulacra, taking photographs of collages and then collaging onto the photographs and then taking one more photograph of those images. 006-002, (2006) Nortse’s work featured in Waves, inverts and fragments the dominant representation of the world in map form, scattering intravenous tubes across the broken world, with plaques in both Chinese and English identifying the illnesses of environmental degradation and misdirected economic development. As many Chinese-to-English words and phrases are mistranslated or misspelled in China, 006-002 captures this subtle, ubiquitous phenomenon, to its own aesthetic effect. When I visited Tsewang Tashi in summer 2006, he was putting the finishing touches on a new home close to the east suburbs of Lhasa, a neighborhood that became the unexpected spawning ground of some of the leading contemporary artists working in Lhasa today, including Tsewang and his apprentice, Tsering Nyandak, both featured in Waves. From his rooftop studio we took in the 360-degree view of Lhasa, from the Potala Palace to the radio tower on old Chakpori Hill, to the mountain Punba Ri, festooned with prayer flags. Tsewang first made his reputation as a landscape artist, illustrating with grace, vivid color, and uncanny perspective the massive brown mountains and broad rivers of Lhasa valley. When, as I wrote in the wall text that accompanied his work in Waves, he went to Norway to pursue a Master of Fine Arts degree from the National College of Art and Design in 2001, he experienced a paradigm shift in his paintings.Introduced to the concept of new-media art, Tsewang Tashi began taking digital photographs of Tibetans, including those of his young daughter in Untitled (2001), and then experimenting with filter effects on them in Photoshop. He would then paint the redesigned photograph, using the same sense of scale and color employed in his landscapes. Tsewang Tashi shifted to portraiture because he wanted to present a new image of Tibetans as “living people,” one that defied the dominance of ethnographic romanticization in favor of subtle studies of emotion and everydayness. Tsewang Tashi is an art professor at Tibet University.

As his students amply demonstrate, his dedication to this next generation

of artists is palpable. His most endearing student, however, is one he

has not taught in school, but rather has informally apprenticed: Tsering

Nyandak. Neither artist shies away from the possibilities embedded in

large canvases, but this is perhaps the only element they have in common.

Nyandak’s canvases sometimes explode in myriad impressionistic layers

of oil color and punctuated brushstrokes, or in smooth, sculpted acrylic

lines that celebrate the luscious curve of a balloon or the contours of

a woman’s body, set in floating, surreal space. The works in Waves

show Nyandak’s more classic approach. While his studio is full of

his newer, streamlined work, Lovers #6 (2003), the last painting in his

possession from a Lovers series he did three years ago, made my heart

contract in a way that shattered the analytical distance with which I

usually approach art. While one may read distinct elements of cultural

and historical context in this painting, the work expresses the tenderness

of sexual and emotional intimacy in human relationships (the first instance

in which I have seen a contemporary Tibetan artwork do so). I tried to

capture the dynamic of interpersonal intimacy embedded in a larger historical

and cultural context in the accompanying wall text: In Tibetan, a word for art is rimo. Yet as I learned while

curating Waves, rimo does not merely correlate directly to art. It was

the artist Benchung who told me the origin of the word, when I visited

him in Lhasa in June 2006. I was lucky to meet Benchung, as he had just

returned to Lhasa on break from pursuing a Master of Fine Arts degree

at the University of Oslo in Norway. I had not seen him for almost a year,

and his English had improved dramatically, while my Tibetan and Chinese

remained tentative, but we nevertheless enjoyed an easy conversation about

his work and the importance of the Waves exhibition. Somewhere in the

trace of our conversation, I used rimo to refer to a painting of his.

Benchung told me this legend: The translation of rimo as art (or, as Benchung explained to me, as all the techniques of art, including painting, drawing, “print, etc.”) may or may not stem from this legend. Nevertheless, clearly rimo can be understood as encompassing something more than just the traditional Buddhist religious scroll paintings, called thangkas, that have typified Tibetan art. Rimo is a more epistemologically expansive concept; it embraces the wider spectrum of possibility and artistic expression we find in the works in Waves. If each artist is inspired by journeys, dreams, beauty, and passion, if each artwork is a search to express, define, capture the ephemeral quality of these inspirations, then we can ask of each artwork, “What dream of rimo is this?” Rimo is a question, a theory with which to approach each

artwork. Just as the mountain’s girl disappears like a rainbow when

we try to apprehend her, so too the artwork resists confinement in a definition.

We must let the journey of encountering the work become the model, the

theory, the question, the contraction of the heart. Through their own

rimo, these artists inspire rimo in us. Their journeys speak to our journeys,

their dreams index ours. In their subjective vision of beauty, they inspire

our own visions of beauty. Rimo is an interactive, multidimensional, intensely

personal, and subjective experience, yet it is still culturally meaningful

and socially and materially powerful. As Benchung scrapes ceremonial chalk

in the shape of his imagination in the middle of an intersection in downtown

Lhasa, or as Namgyal Dorjee paints from his dreams of a woman giving birth,

or as Kesang Lamdark shows us what shape light can take in the darkness,

rimo is a force active within them all, a force we viewers feel when we

apprehend their artworks, a force we will all feel long after Waves. |

Footnotes: 1.Tamar V. Scoggin, 2005. “In the Studio: Imagination, Inspiration and Influence.” Guide to the exhibition Old Soul, New Art: The Works of Three Contemporary Tibetan Artists. Mechak Center for Contemporary Tibetan Art. 2. Benchung has povided

a citation for this legend: Tibetan Painting (written in Tibetan and Chinese)

by Tenpa Ropten, a thangka painting teacher at Tibet University, year

unknown. |

Waves on the Turquoise Lake main exhibition

Acknowledgements | Biographies

Seeing Into Being: The Waves on the Turquoise Lake Artists' and Scholars' Symposium - Carole McGranahan and Losang Gyatso

Waves on the Turquoise Lake: Contemporary Expressions of Tibetan Art - Lisa Tamiris Becker