Lisa

Tamiris Becker

Making Waves: The Rimo of Curating : Contemporary Tibetan Art Through an Anthropological Lens - Tamar Victoria Scoggin

Seeing Into Being: The Waves on the Turquoise Lake Artists' and Scholars' Symposium - Carole McGranahan and Losang Gyatso

Acknowledgements | Biographies

Waves on the Turquoise Lake main exhibition

|

Lisa

Tamiris Becker |

| The Image, the imagined, the imaginary—these are all terms that direct us to something critical and new in global cultural processes: the imagination as a social practice. No longer mere fantasy (opium for the masses whose real work lies elsewhere), no longer simple escape (from a world defined principally by more concrete purposes and structures), no longer elite pastime (thus not relevant to the lives of ordinary people), and no longer mere contemplation (irrelevant for new forms of desire and subjectivity), the imagination has become an organized field of social practices, a form of work (in the sense of both labor and culturally organized practice), and a form of negotiation between sites of agency (individuals) and globally defined fields of possibility. . . . The imagination is now central to all forms of agency, is itself a social fact, and is the key component of the new global order... |

|

...The central problem of today’s global interactions is the tension between cultural homogenization and cultural heterogenization… …Most often, the homogenization argument subspeciates into either an argument about Americanization or an argument about commoditization, and very often the two arguments are closely linked. What these arguments fail to consider is that at least as rapidly as forces from various metropolises are brought into new societies they tend to become indigenized in one or another way: this is true of music and housing styles as much as it is true of science and terrorism, spectacles and institutions. The dynamics of such indigenization have just begun to be explored systemically.… — ARJUN APPADURAI, MODERNITY AT LARGE [1] |

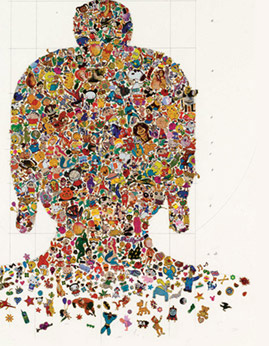

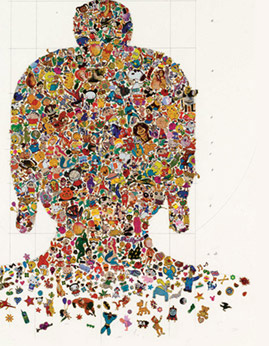

Waves on the Turquoise Lake: Contemporary Expressions of Tibetan Art is the first major museum exhibition to bring together contemporary Tibetan artists working both in and outside Tibet. Featuring works by Benchung, Dedron, Namgyal Dorjee, Gade, Gonkar Gyatso, Losang Gyatso, Jhamsang, Kaltse, Kesang Lamdark, Nortse, Tsering Nyandak, Karma Phuntsok, Tenzing Rigdol, Samchung, Shelka, Sodhon, Tsewang Tashi, and Migmar Wangdu, the exhibition highlights the emerging movement of contemporary Tibetan art as it appears in Tibetan communities across the globe. From reinterpretations of Tibetan Buddhist religious scroll paintings (thangkas) to digital and installation art, contemporary Tibetan art explores issues of tradition versus modernity, cultural hybridity, and personal identity through a diverse range of media and perspectives. The exhibition features works that address the complexity of the Tibetan diasporic experience and includes Tibetan artists from Australia, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States, and India, as well as those from Tibet. Artworks on view also address current transformations within Tibet, such as the recent coming of the first train to Lhasa, the environmental challenges posed by ongoing land development, and the increased influence of new communication media such as film, television, and the Internet. Artworks that poignantly reconfigure traditional Tibetan painting techniques, icons, and spiritual imagery are among the highlights of the exhibition. Tibet as a nation has always been a complex notion, embodying numerous regions of the Tibetan plateau and the surrounding geographies, as well as myriad Buddhist sects, dialects, and fusions of ethnicities. “Contemporary Tibetan art” is equally indefinable in a single sense. It is the goal of Waves on the Turquoise Lake: Contemporary Expressions of Tibetan Art to present the great range of subjects, methods, and artistic approaches that encompass contemporary Tibetan art, while at the same time giving voice to a burgeoning field that is only now gaining a larger foothold in the international dialogue of the worlds of art. Arjun Appadurai has insightfully addressed the primacy of imagination in the processes of contemporary globalization.[2] Similarly, the appreciation and circulation of “art”—and more specifically of “contemporary art”—is of increasing significance and importance to artists, communities, and audiences both within Tibet and across the global community. While traditional Tibetan art has long been a locus of desire internationally and has been gaining an ever-increasing audience of appreciators and collectors, however fraught with paradoxes and problems, the notion of contemporary Tibetan art as a practice in which expressions of both tradition and contemporary experience are intertwined is somewhat new. However, the desire to develop a contemporary Tibetan art has a long history within the culture; for example, the twentieth-century artist Gendun Choephel has now become an “icon” of modernity within the Tibetan artistic community. (Many of the Lhasa artists in the exhibition helped found and participate in the Gendun Choephel Artist Guild, which is one of the few active art venues in Lhasa devoted to contemporary art.) As a sign of the proliferation of contemporary art within the rapidly changing urban world of Lhasa, the exhibition also features a work by Migmar Wangdu, a member of a newer group composed of younger artists, the Shunue Dame Artist Guild. Today, gallerists in Europe, Australia, the United States, and Asia are paying close attention to contemporary Tibetan art and this interest is likely to accelerate as the agency of the individual artists continues to develop and the markets and audiences increase. If, as Appadurai, says, “the central problem of today’s global interactions is the tension between cultural homogenization and cultural heterogenization,” then contemporary Tibetan art is a powerful mode of expression of this vital tension. But as Appadurai articulates, the homogenizing forces cannot be thought of simply as a form of “Americanization,”—a term wholly inadequate to capture the cultural and social transformations that are occurring across Tibet.[3] Numerous dominanteconomies are vying for control of Tibet’s development and this process is accelerating. Many of the artists in Waves on the Turquoise Lake capture this transformation and the concerns it brings for the future—indeed, the survival—of Tibet, particularly problems of environmental degradation, loss of cultural history and tradition, and overpopulation. These problems are most overtly expressed in the work of Nortse and Gade, whose poignant commentaries ominously presage the future of Tibet, should action not be taken to restore environmental balance. Nortse’s powerful mixed-media work presents a lacerated inverted map of the world to which he has affixed intravenous tubes with suspended tags inscribed with the various dangerous methods of environmental destruction that confront Tibet and the world at large (mining, overpopulation, pollution, etc.). Similarly, Gade’s magnificently painted panorama, New Tibet (2006), is a futuristic image of Tibet painted subtly on long, thin horizontal paper, shaped to emulate a traditional Tibetan manuscript page. The surreal scene is complete with world trade towers, trains, and UFOs, which appear amid the high mountains and magical clouds that have defined Tibet and Tibetan landscape painting for centuries. The work is painted with subtle mineral colors, a technique that unites traditional thangka painting with a cartoonlike illustrative style, heightening the strategy of irony and critique that motivates his work. In a related work, Nirvana (2006), Gade fuses Buddhist iconography with Disney’s Mickey Mouse, perhaps to comment on the all-encompassing Disneyfication of global civilization, even that of the most remote regions of the world. Alternatively, this provocative work can be thought of as capturing the all-encompassing meaning of Buddhism, which by definition must embrace and incorporate elements that at first appear inherently profane, such as Mickey Mouse and other icons of popular culture. Like Gade, Dedron, an artist from Lhasa, has also made a long horizontal painting, Lost Horizon (2006), that depicts the vast expanse of the Tibetan world. Her style, distinctly self-taught, captures with a folk charm and complexity the mountainous landscapes and villagescapes that unfold across Tibet and that have become beloved images of the imagined Tibet, both within and outside its borders. The divergent aesthetic and representational approaches seen in Waves on the Turquoise Lake reflect the broad-ranging artistic training of Tibetan artists today. The importance of this point must not be underestimated if we are to understand the hybridity of Tibetan art and its sources. The artists in Waves on the Turquoise Lake have received schooling that ranges from traditional Tibetan thangka painting to training in Chinese art academies with an emphasis on the representational traditions of Social Realism, to training in European and American art schools, where young artists are exposed to multiple artistic approaches, including realism, abstraction, and conceptualism. Several of the artists are also self-taught. While the work of artists such as Tsering Nyandak and Tsewang Tashi is clearly influenced by Chinese Social Realism and the lineage of that painting tradition which is linked to the influence of Russian Social Realism and European Impressionism, they nonetheless focus this practice and technique on distinctly Tibetan subjects. Nyandak’s sensitive and moving paintings draw on Post-Impressionism, particularly the work of Vincent van Gogh; like van Gogh, he focuses on everyday figures. However, his work is decidedly contemporary in its social content. In paintings such as Lovers #6 (2003), and Police Phobia (2004), he captures the daily experiences of intimacy, desire, and fear in the lives of average Tibetans. Tsewang Tashi’s ambitious paintings are full-frontal portraits of young Tibetan girls. The paintings have a high-tech quality, as if painted from computer-manipulated portraits that lean toward the hyperreal. The over-scaled portraits confront the viewer with piercing expressions of beauty and vulnerability. Works of digital art and performative video art by Kaltse and Benchung, who work in Tibet, embrace these new media as viable and rich forms of artistic expression. This new wave of digital photography and performance video propels Tibetan contemporary art into full dialogue with movements of the global art world and allows subjects of importance to contemporary Tibet to circulate in that dialogue. The works of the many Tibetan artists in the exhibition who live in exile communities across the globe manifest the hybridity of their artistic training. Karma Phuntsok, for example, received traditional thangka training and also studied under an Australian aboriginal master painter after moving to Australia. Phuntsok’s potent fusion of these two methods in works such as the magnificent Vajra (2000), allows him to achieve a new form of mastery previously unseen in the art world, a fusion of two disparate traditions that is seamless, both aesthetically and conceptually. Similarly, in Invocation of the Buddha (1999) Phuntsok fuses traditional Buddhist iconography with a subtle celestial field of blue, painted with expressionist brush strokes of blue, white and green acrylic paint, thereby intertwining painterly and philosophical notions associated with abstract expressionism and with traditional thangka painting. The work of Tenzing Rigdol, who received thangka training in Nepal and more recently completed art school in Denver, Colorado, focuses on cultural fusion as both a practice and a subject. Rigdol’s work intertwines Hindu, Buddhist, and Western iconography and philosophical references to create layers and slippages of meaning. In addition to art training in Denver, Rigdol has studied philosophy and his work interweaves the philosophical traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism, and French deconstruction with a decidedly hip, even punk sensibility. Gonkar Gyatso, who lived in Tibet, then went into exile in Dharamsala, India, and later immigrated to the United Kingdom, also fuses numerous representational and conceptual approaches in his work. His carefully mapped sticker pieces, such as Buddha@hotmail-1 (2006), Panda Politics* -1 (2006), and Pokemon Buddha (2004), reveal his training in traditional Buddhist painting, in which figures and deities are carefully mapped on a grid to achieve preset idealized proportions. He plays with the Buddha as an icon that, ironically, has achieved a cult status in European and American society to investigate the contemporary meaning of Tibetan Buddhism and, by implication, Tibet itself. He intelligently fuses conceptualism and traditional Buddhist iconography to examine the fetishization of Tibet and Buddhism in the imagination of the West. In his performative photography work My Identity (series of four) (2004), he explores the identity pressures of the various cultures in which he has lived, as well as another identity he now also inhabits: the London artist. Kesang Lamdark was adopted by a Swiss family and educated in Switzerland and New York City, where he attended graduate school at Colombia University. He creates “Swiss” style installation art whose subject nonetheless focuses on Tibet. In Warhol of Tibet (2006) Lamdark refers not only to the Warholian notion of the contemporary icon, but also to several works by Marcel Duchamp, including The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even (1915–23), and his Étant donnés (1946–66). Lamdark, like Duchamp, allowed the accidental breakage of large panels within his installation to become part of his work. He also embraces the Duchampian notion of the Ready-made, with beer cans attached to a suspended sheet of glass in the center of the installation. Although the citation of Duchamp is clear, it is not simple. In strong contrast with Duchamp’s Ready-mades, Lamdark’s beer cans are pierced with carefully crafted images and icons that transform them into intriguing tin light boxes. He worked with a photographer to create powerful C-prints of the backlit beer-can imagery; these are installed along the walls of the installation, each print corresponding to its respective beer can. The beer cans also refer to Duchamp’s final work, Étant donnés, a three-dimensional installation that viewers observe by peering through a small peephole to witness an artistic diorama. But Kesang Lamdark’s peepholes reveal wholly different subjects: Tibetan imagery ranging from demons to Rinpoches, and skateboarders to lamas, or spiritual teachers. The work of Losang Gyatso, who was born in Tibet and has lived in exile in India, the United Kingdom, and now the United States, sensitively bridges tradition and modernity. Manifesting his training in graphic arts, his paintings explore traditional Tibetan iconography, while also investigating the painterly challenges of color and the tension between representation and abstraction. Particularly in his recent work, such as Dancer in the Empty Sky (2006), and Three Flaming Jewels (2006), Losang Gyatso explores the subject of presence and absence, long a significant subject for painters in both Asia and the West. While these paintings each cite traditional Tibetan Buddhist subjects: “the dancer” and the “Three Flaming Jewels (Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha),” Gyatso is interested in the deeper meaning of these concepts, rather than in merely depicting their iconography. He sensitively layersbands of color so that the iconography appears and dissolves into a greater abstract field. Losang Gyatso is also particularly interested in pre-Buddhist Tibetan shamanic culture and has studied ancient Tibetan rock carvings. Securing the Shadow, Stilling the Sun (Homage to Virupa) (2004), masterfully depicts the famous Buddhist story of Virupa, who is able to control both the sun and its shadow with a spiritual dagger, as a symbol of his control over mind and body. Gyatso’s representation of the story is at once illustrative and painterly, traditional and contemporary, and transposes traditional Tibetan subjects to the contemporary realm of acrylic on stretched canvas. This is a new direction for Tibetan painting; it incorporates compositional cropping and shifts of scale—aesthetic methods borrowed from Western painting traditions—with distinctly Tibetan decorative and iconographic imagery. The exhibition also features work by several artists living in the Tibetan exile community of Dharamsala. Works by Samchung, Sodhon, and Namgyal Dorjee reveal the influence of oil painting on canvas and the Social Realist tradition emanating from Tibet, as well as the exploration by many Tibetan artists of abstraction as an effective method of expressing Tibetan Buddhist ideals. The work of Namgyal Dorjee, Woman (2006), also exhibits a strong Indian influence, as its metamorphic image is painted on buckram cloth, traditionally used to stiffen Indian shirt collars. If any single point can be said to encompass the vast array of subjects, objects, and aesthetic approaches comprising Waves on the Turquoise Lake: Contemporary Expressions of Tibetan Art, it is that contemporary Tibetan art is at a vital crossroads of manifestation and circulation and that audiences across the world await further expression from the passionately committed communities of Tibetan artists living both in Tibet and in the diaspora. |

Footnotes: 1. Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 31–32. 2. Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, 31–32. 3. Arjun

Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, 31–32.

|

Waves on the Turquoise Lake main exhibition

Acknowledgements | Biographies

Seeing Into Being: The Waves on the Turquoise Lake Artists' and Scholars' Symposium - Carole McGranahan and Losang Gyatso

Making Waves: The Rimo of Curating : Contemporary Tibetan Art Through an Anthropological Lens - Tamar Victoria Scoggin