Previous Chapter | Table of Contents | Next

Chapter

THE OLD CITY OF LHASA

REPORT FROM A CONSERVATION PROJECT (98-99)

6.1 General THF Strategy

In 1996, the THF signed an agreement with the municipal authorities to jointly

undertake a restoration and infrastructure programme with the aim of rehabilitating the

old city. THF financed and supervised the restoration of two historic residential

buildings located immediately to the north of the Jokhang temple front, the Trapchishar

and Choetrikhang houses (for more detail refer to the 1996-97 THF first annual report).

Since during 1996 and 1997 old houses were still being demolished, THF placed high

priority on urgently preserving intact neighbourhoods and clusters of historic buildings.

For practical reasons, it was decided to establish a model conservation area, which should

be centrally located. In this area, restoration and infrastructure improvement projects

should be planned and implemented together with the local residents and the authorities.

The work should then have positive influence on the rest of the old city. However, even

while concentrating on the work in the first conservation area, THF continously lobbied

for official protection of all the remaining historic buildings or at least of the more

important ones. To this end, documentation and study work was being carried out in several

parts of the city, and urgent relief work planned.

6.2 The THF Conservation Area Concept

The THF principles for the Lhasa old city programme are perhaps best represented by the

German model of "behutsame Stadterneuerung" ("careful urban renewal"),

adapted for the Tibetan context and with strong emphasis on architectural conservation.

Different concepts of restoration and conservation are suitable for different situations

and needs. Conservation of monuments and historic buildings transformed into showcases

open for visitors qualifies for the museum-type approach in conservation. Inner city areas

populated by ordinary tenants qualifies for an approach that fully integrates the

concerned part of the population. The German model places equal emphasis on the

preservation of historic areas in their contemporary urban context and on infrastructure

improvement based on actual needs, with a grass-roots approach where residents and

planners meet. Driving principles of sustainability and ecological concerns are achieved

by involving the local community in the planning and implementation of the programme, and

by developing individual solutions and necessary new technologies. For implementation at

micro-level, a larger district is divided into different conservation areas

(Sanierungsgebiete). This approach was deployed in the 1980s in the old Kreuzberg district

of Berlin (West), after local residents successfully protested against a large-scale

government redevelopment programme of a severly dilapidated historic district.

In the Tibetan tradition, only the most valued building elements (such as revered

religious murals or structural elements with historic connotations) would be preserved in

their original state. In most cases, when necessity warranted repair works, old buildings

(monasteries and manor houses alike) were often partially rebuilt and in the process

modified according to contemporary taste.

The immense loss of historic structures in Tibet during the 1960s should warrant the

preservation of as many of the scarce remaining historic structures as possible. The

events of 1959 have produced a brutal break in the gradual cultural development of Tibet.

Monasteries, forts, palaces and manor houses were destroyed during the Cultural

Revolution. Master craftsmen were persecuted. Most crafts have been radically re-organised

(in the form of state-run construction companies), and new materials that are

comparatively cheap and easily available have been introduced (eg cement). This has caused

many traditional techniques to fall into disuse. The modern development of Lhasa will

certainly go on and will find ample space in the Lhasa valley. The comparatively small

size of the old city (less than 5% of the present city area), and the

cultural and historic value of its ancient structures, now justify the introduction of

internationally-accepted approaches to conservation.

|

Trapchishar House, restored by THF in1996 |

|

The THF subscribes to the charter of ICOMOS (listed in the appendix). Recent

rehabilitation projects carried out successfully in the kingdom of Nepal (a Himalayan

neighbour of the TAR) are also being taken into consideration by the THF. Most important

however is the research undertaken by LAP since 1993 into the traditional architecture and

lifestyle of the Lhasa old city.

In project research carried out, the two points raised most often by Lhasa residents

when talking about the old city were:

- a wish to preserve the historic cultural identity of the old city

- a desire to improve living conditions

Having examined the situation in Lhasa, the THF has decided to concentrate its efforts

on the preservation of at least one intact neighbourhood in the old city. Thus several

different styles and grades of traditional Tibetan architecture can be preserved in their

original context. The THF views as essential to the success of the conservation programme

a good cooperation with the authorities to ensure the proper protection of listed

buildings and the smooth implementation of programme activities,

combined with a grassroots approach for the drafting of the conservation plan. Altogether,

the THF hopes to contribute to a lasting local conservation policy and achieve sustainable

improvement of living conditions.

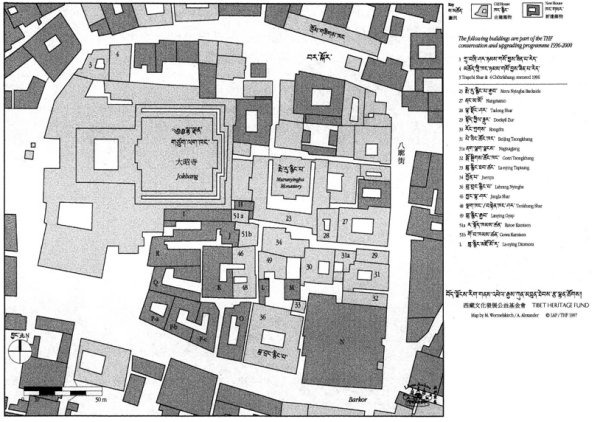

6.3 The Ödepug Conservation Area

The THF chose a neighbourhood comprising fourteen old residential buildings (12 of

which are owned by the government) to be turned into a model area. This area, known by the

ancient name of Ödepug, is located inside the south-eastern section of the Barkor. It is

accessed by two very narrow alleyways, the Ödepug Sranglam and the Ngakhang Sranglam. The

neighbourhood is adjacent to the Jokhang temple, whose golden spires can be seen from

several viewpoints in the area. It was in this area that the workers who built the Jokhang

temple in the 7th century set up their quarters, and even the royal court had, according

to popular legend, put up residence on the site of several of the buildings existing

today. The exact meaning of the name "Ödepug" is unclear. The name probably

either means "area being under command of a higher place", referring to the

Marpori palace of king Srongtsan who personally oversaw the construction of the Jokhang;

or is a corruption of "Ulaypug", meaning the area of ulay workers, ulay being

the Tibetan term for corvée labour.

THF agreed with the municipal government on a cooperation project with the aim to

create a conservation model area by restoring the old buildings in the Barkor Ödepug

area, and to make improvements in the fields of water and sanitation. The Lhasa City

Cultural Relics Office backed the proposal. Because of the proximity of the area to the

Jokhang temple (a listed national monument), where restrictions on new construction had

already been placed, official cooperation was easy to obtain. THF therefore began the

necessary studies and social surveys. Each house was visited, and the residents were

involved in the planning stage of the project. This was received very positively by the

local community. Official support and collaboration during the first programme stages have

so far been quite positive.

With the recent development and transformation of Lhasa in general, and even of most

quarters of the old city, the small quarter chosen by THF as first conservation zone

already appears like a relic from another time, so different are the dimensions and pace

of life. Rather than see the alleyway turned into a business quarter with hotels, banks

and souvenir shops overtaking the houses, THF hopes to revitalize the neighbourhood by

involving the inhabitants in the process of improving the general living conditions. To

this end, many modifications and alterations are planned that aim to redeem some of the

problems described in previous chapters. This plan goes beyond the purist museum-type

approach to conservation, but is important for the revitalization of the neighbourhood.THF

will certainly retain as much original substance and traditional architectural fabric as

to guarantee the preservation of the authenticity of the area and the original

architectural diversity.

6.4 Social Survey in the

Conservation Area

An overview of the housing situation in Ödepug, based on the 1997 social survey

carried out by Pimpim de Azevedo.

The survey conducted by THF covered 14 old buildings in the Ödepug area. All 14 were

originally built as residential houses. The majority were owned by well-to-do families,

who lived in rooms on the upper floors of the houses and kept their livestock below in

rooms off the courtyard. One house, Doekyilzur (29), had a shop on the ground floor for

the family business. A few of the buildings, such as Nangmamo (27 ), were purpose-built

tenement blocks. Nangmamo also has shops on the ground floor facing Barkor street. In

Ödepug street itself, there are no shops.

When buildings in Lhasa were nationalised, after 1959, most of the old residences in

Ödepug were made into Public Housing. Some buildings, however (29, 31, 49, 46), are

privately owned. Buildings taken for Public Housing were divided up into flats so that

each would house many families. Even rooms on the ground floor, intended as store rooms or

animal sheds, were taken over for human habitation. Unfortunately, the converted old

houses, without regular building maintenance, stressed by over-occupation and not designed

for innovations such as running water, are now in a state of considerable dilapidation.

Privately owned houses have fared much better. In the survey, THF tried to gauge current

occupants' opinions on the state of their homes and how this might be improved. Many

interesting aspects were discovered, which must be considered when planning future work in

the area.

Ownership, Maintenance, Renting and Sub-renting.

The Public Housing buildings in Ödepug are managed by the Lhasa Housing Office, which

also allocates the flats within the buildings. Until the 1980s, allocation was strongly

influenced by a person's social background. Better flats were given to those who had been

of the "oppressed classes," whilst those with aristocratic connections might

find themselves living on the ground floor in the old stables. Nowadays it is more or less

a matter of luck as to whether one is allocated a good or bad flat. Government housing in

Ödepug is heavily subsidised. Typical rents for a family are 3-23 RMB per year (compared

to 150-350 RMB per month for similar private sector accommodation). Poor or infirm people

are exempted from paying any rent. In some cases, the classification as "poor"

was made in the 1960s and has not been revoked, despite a family's rise to relative

prosperity.

Some families have become rich enough to rent better accommodation elsewhere and are

now sub-letting their Ödepug government housing. Sub-tenancies are often taken up by

people who are not registered in Lhasa and therefore are not eligible for housing in

government-owned buildings. Sub-rents of up to 250 RMB per month are charged, a

substantial profit for the official tenant. Subtenants are effectively powerless to

complain about poor housing conditions since it is illegal for them to live in Lhasa in

government housing.

One of the first observations to be made in Ödepug was that the public alley was a lot

cleaner than many others in Lhasa, and that the courtyards of the individual buildings

were also regularly kept clean. The people of Ödepug are mostly long-time Lhasa

residents, who like their neighbourhood and sweep their courtyards. However, the residents

lack a feeling of ownership for their houses and therefore do not undertake major

maintenance jobs themselves. Although crisis repairs are carried out, maintenance tasks,

such as oiling an arga roof every year or stamping fresh soil into a soil roof, are not

done. The Neighbourhood Committee, responsible for regulating all activities within the

houses, does occasionally offer assistance in paying for some repairs, especially where

toilet towers have collapsed. The Housing Office is not in a position to offer assistance.

In the 1980s, a plan was made to have all the old buildings in Lhasa replaced by the year

2000. Execution of this plan is mainly in the hands of the Planning Office, often

following recommendations from the Housing Office. With the future of the buildings so

uncertain, there is little incentive to invest in renovation work. When asked for help,

the Housing Office can only beg the residents to be patient until their house is

demolished and replaced by a new building. An additional effect is

that residents feel unsure about the future of their house and are less motivated to carry

out even minor repairs themselves.

|

| Conservation area Oedepug alleyway |

|

Living Space, Facilities and Condition of Buildings.

The living spaces in the old houses have not adapted very well to division into flats.

Rooms purpose-built as, for example, kitchens, reception rooms, or shrine rooms were

reallocated to house entire families. In the new setup, residents have had to improvise

kitchen areas or shrine rooms for themselves. Toilets which were designed for the use of

one household might now serve 20 families.

Residents often expressed concern about damp in the structure of the houses, especially

around the toilet vault, and because of leaking roofs. The mud mortar joints are weakened

by excessive damp and have been known to fail in several old houses. Since

nationalisation, some modern developments have led to an increased likelihood of damp.

Originally the buildings were designed for an arid climate where toilet vaults were kept

dry by the addition of ash, and water was supplied from wells. The change from yak dung to

gas and kerosene as the main cooking fuels has led to a shortage of ash for adding to

toilet vaults. New inadequately drained water taps and frequently blocked drains

exacerbate the problem.

Within a typical 3-storey house a great variation between the quality of flats on

different floors was found. Third floor windows are large and rooms have a good amount of

light. In rainy weather, however, the roof often leaks. One cause of considerable concern

for some 3rd floor tenants is that their floor is the one furthest away from the courtyard

tap. Usually older people said that they would prefer not to live on the 3rd floor since

they find it hard to carry water up from the tap.

The second floor of the house seems to be the most popular amongst residents. Some

second floor residents were concerned about unsafe pillars or beams in their flats, but

most were satisfied with their accommodation.

The least desirable rooms are on the first floor (ground floor). Here in rooms intended

as store rooms or animal shelters, there are few or no windows. The rooms are therefore

always dark and damp. One particularly unpleasant problem found was in rooms next to the

toilet vault. Often the vault walls are damp with urine and some actually leak into the

flats. A similar problem is encountered in flats with one wall to the street. Poor

drainage means that in wet weather the street is often awash with unsanitary water which

can seep in through the walls. In addition, passers-by frequently urinate on the house

walls.

Some of the residents were dissatisfied with their accommodation and concerned about

the condition of the building they were living in. In cases where residents have asked to

be rehoused, they have been told that they could only be moved into flats in a worse state

than their present accommodation.

The Demolition and Replacement Option.

In the 1980s, the decision was taken by the planning authorities in Lhasa to demolish

all old public housing buildings and replace them with new ones. Due to THF's efforts,

this policy is now being reconsidered. Reasons given for the policy are that the buildings

would be too expensive to repair, are structurally unsafe and lack good sanitary

facilities. Other reasons might be the considerable sums to be made by replacing a

2-storey building around a large courtyard with a 4-storey building around a small

courtyard. Residents from the old flats are rehoused in similarly sized accommodation and

the remaining flats can be sold or rented out. The rents which can be charged for a flat

in a new building are much closer to those charged in the private sector. Residents

rehoused in a new flat after demolition of their old building might now be charged in one

month what they would previously have paid over 10 years. The quality of the new buildings

means that they are not very expensive to build, making this an attractive option for the

developers. Unfortunately for the tenants, the water supply and toilets in the new

buildings are similar to those of the old houses, but must be used by many more families.

Opinions amongst residents varied on the demolition and rebuilding issue. Those living

on the ground floor often welcomed the idea of moving into a new building since their

conditions would undoubtedly be improved. People living on the upper floors were not so

keen for change. Most of the older people did not want the building to be demolished since

they had lived much or all of their lives in their present flat. Many people were aware of

the shortcomings of the new buildings, including thinner walls, poor concreting, lack of

light and increased population. The situation, however, is such that the only hope of

improvement that has been offered to tenants by the authorities is the demolition and

replacement of their buildings. This was often seen as an inevitable outcome which people

would rather get over with than have hanging over their heads indefinitely. Most residents

were very interested in the 1996 THF restoration of nearby Trapchishar house. Many said

that they thought the people at Trapchishar should have been more involved in the project.

This must be taken into account when restoring the Ödepug buildings.

6.5 Consequences

Store-rooms and stables have been transformed by the Housing Authorities into living

quarters with mixed success. Scarcity of housing in Lhasa, and the lack of need for

stables due to social changes rule out any reconversion into stables again. Rather, one is

faced with the difficult task of turning dark and humid rooms into decent and acceptable

living space. One solution is to encourage the building of public housing elsewhere to

offer alternative space for those not wishing to live on the ground floor, and then turn

the free rooms into storage or shops. Otherwise there is a need to provide extra windows,

and added insulation and improved air circulation to counteract the dampness.

THF generally prefers to preserve the facade of a historic building as much as

possible, and restore it by opening up blocked windows and doorways. New windows and

doorways where unavoidable should blend in well with the original design.

Attention must be paid to keep the courtyard open, for use as communal space and to

allow maximum sunlight penetration of the building. Removal of extensions in the courtyard

or visible from the street is recommended, but this sometimes requires a good deal of

persuasion. Some courtyards, like Jagdrak House and Thentong mansion (one of the 76 houses

listed in chapter 4.4) have the entire courtyard built up and blocked by numerous

extensions. Similar extensions can be found on many rooftops (the one on Rongda House is

particularly annoying), but can be partially redeemed by "disguising" them with

traditional features that blend with the original design of a house.

In the interior, much more liberty can be taken to improve and modify the house

according to requirements. Some rooms that have surviving murals or rich carvings on

building elements deserve more attention, and the inhabitants and the authorities are

asked to make a special agreement under which the tenant takes the responsibility to look

after these important details, with the Cultural Office in posession of a full list of

descriptions of the details concerned.

6.6 The Individual Houses

in the Conservation Area

(numbers refer to the map given under 6.3)

23 Murunyingba monastery

The Murunyingba site dates back to the founding of the Jokhang temple. By the 9th

century, a small temple with circumambulation path had been established, which still

exists today. In the 17th century, the Fifth Dalai Lama enlarged the monastery by adding a

four-storey temple building and a large courtyard, and made it into the Lhasa city

residence of the Tibetan state oracle Nechung. A Sakyapa-shrine is also part of the

complex. During the cultural revolution, the monastery was closed, but

not destroyed. Today, the three individual temple rooms are open to the public, while the

former monk quarters built around the courtyard have been converted into public housing.

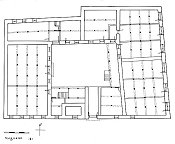

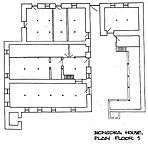

27 Nangmamo

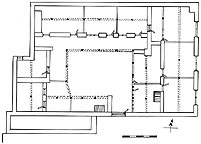

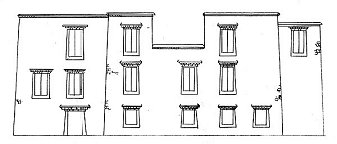

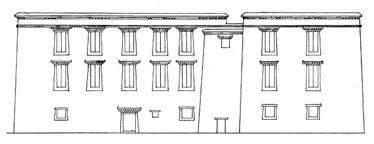

|

| Nangmamo House, floor 1, JJ |

|

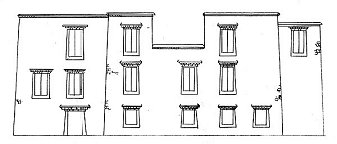

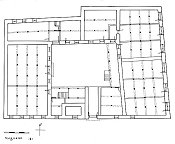

A large tenement yard that was previously owned by Ganden monastery. A large

former monks' assembly hall and adjacent kitchen on the ground floor have been given back

to Ganden, the rest is government-owned and inhabited by tenants. The shops on the ground

floor facing Barkor street are connected via trap-doors with the flats above. Many flats

are overcrowded (one family with children that lives on the top floor only has one room).

Main problems are cracks in walls, leaking roof and infiltration of liquids from the

toilet into adjacent flats. The toilet is also in a precarious condition. The building has

two important facades facing Barkor and Ödepug streets. Its history

dates back to the founding of the Jokhang, but the present structures are probably

18th-19th century.

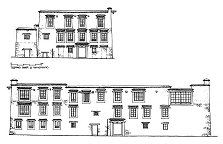

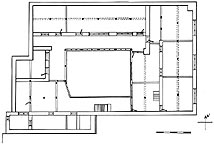

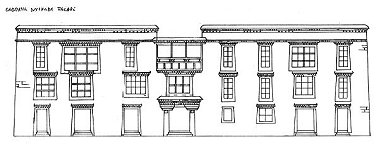

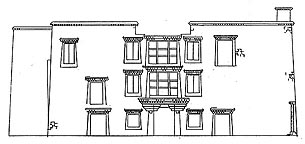

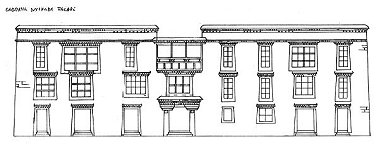

|

Tadongshar and Nagmamo, south elevation

along Oedepug alley, JH |

|

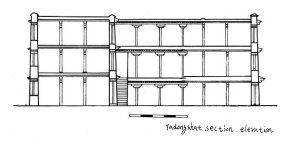

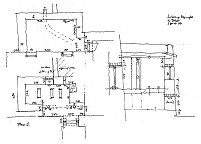

28 Tadongshar

One of the oldest buildings in the area, currently

government-owned. Main problems are cracks in the walls, leaking roof, and infiltration of

toilet liquids into main walls and adjacent rooms. The residents try their best to

maintain the house and to keep the courtyard and entrance area clean. The house in its

present form is at least 200 years old, but its history dates back to the 7th century when

it was a caravanserai and guest house for visitors of the Tibetan royal court.

|

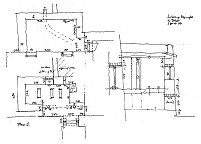

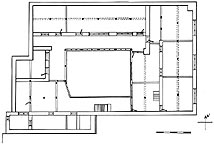

|

Tadongshar, ns axis section |

Tadongshar, courtyard elevation,

south-facing, JJ |

|

29 Doekyilzur

This building with groundfloor shops on Barkor street has recently changed owners. The

new buyer has asked the THF for assistance in necessary repairwork. There are cracks in

walls and floors. The house has some very beautiful architectural details. It dates back

to the 1920s.

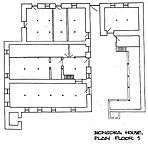

30 Rongda - this is a very significant houses, built with excellent craftsmanship and

elaborate and artistic details. The main building is in reasonable condition, but parts of

the courtyard gallery are sinking. A lower courtyard building has recently been repaired,

and an ugly extension on the roof spoils the view of the building from afar. The toilet

section is in some danger of collapsing. A small space behind the house, once a

through-way to Barkor street, is now blocked by new construction and

full of accumulated waste. The house had no water for most of the day when the

investigation began (see chapter 7). Built in the 1930s, Rongda is one of the latest

buildings in the conservation area.

|

|

Rongda, west elevation |

Rongda, main building, east elevation |

|

|

|

|

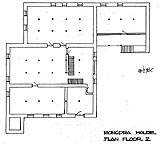

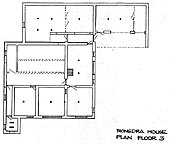

Rongda House, plan floor 1 |

Rongda House, plan floor 2 |

Rongda House, plan floor 3 |

|

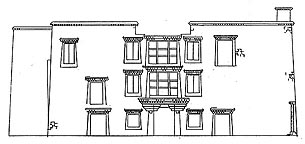

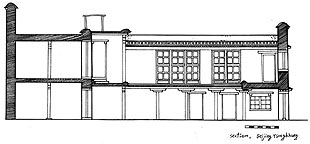

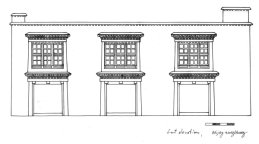

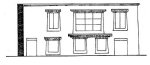

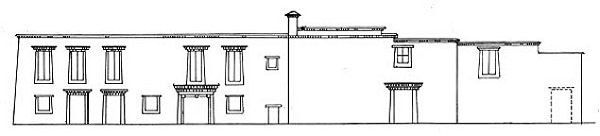

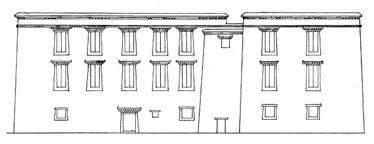

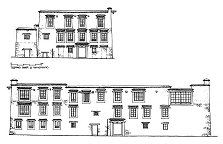

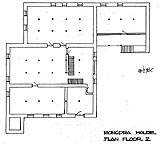

31 Beijing Tsongkhang

This building has an important Barkor facade, and some very nice interiors. Built

around the 1920s, one part of the house today is privately owned.

|

|

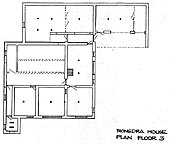

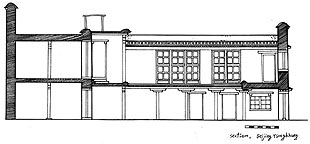

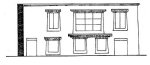

Beijing Tsongkhang, w-e

axis section, JJ |

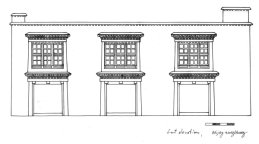

Beijing Tsongkhang, east elevation facing

Barkor Street, JJ |

|

|

|

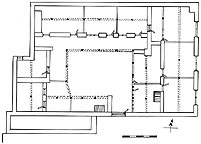

| Beijing Tsongkhang, floors 1 and 2,

JJ |

|

31a Nagtsagjang

This three-storey house has an important facade on Ödepug street, but the insides are

simple and dilapidated. The age is unknown.

34 Juenpa - with two courtyards and a very long wall along and several important

corners on Ödepug street. The bigger courtyard has been filled up with extensions,

some of them only sheds, others more permanent, each of them housing one family. Condition

of the main building is sound. The history of the house dates back to the 7th century, and

until the 1960s an important shrine was preserved in the building.

|

|

|

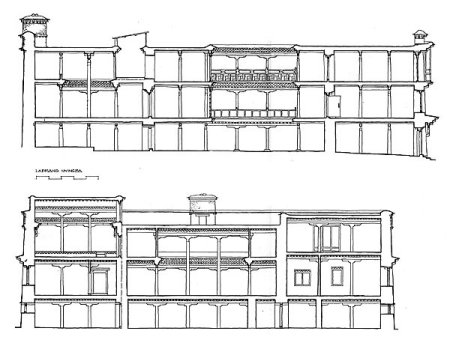

Juenpa, floor 1, DJL |

Juenpa, main building elevation facing south towards courtyard, DJL

|

Juenpa, west wing elevation facing towards

courtyard |

|

|

Juenpa, west wing elevation facing west

towards Oedepug alley |

|

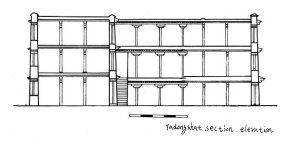

36 Labrang Nyingba - the most important building in the area. It was founded in the

15th century as residence for the founder of the Gelukpa order, Je Tsongkhapa. It has

since been repaired, refurbished and partially rebuilt. The craftsmanship displayed in the

present structures, a lay-out that is both pleasant and imposing, and the richness of the

decorative details make this one of the best illustrations of the qualities of Tibetan

architecture in all of Lhasa. The municipality had already earlier placed the building

under protection because of its historic significance. There are some cracks in the walls,

the back toilet may collapse soon, some parts of the top floor have already collapsed

partially, and still the building is somehow imposing and noble in appearance. The

development of a suitable rehabilitation plan is now regarded as a

priority for both the local community and the THF

|

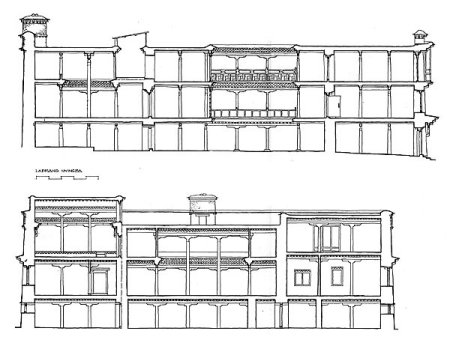

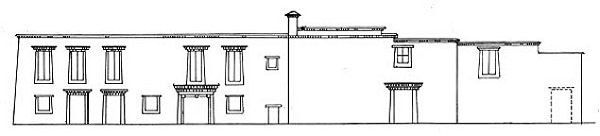

Labrang Nyingba, n-s section, JH |

| Labrang Nyingba, w-e section, JH |

|

Labrang Nyingba, east elevation, DJL |

|

|

|

|

|

| Labrang

Nyingba, floor 1-3 and roof, DJL + JH |

|

| Labrang Nyingba, south evlevation

facing Barkor Street, DJL |

|

46 Jangla Shar - this was probably conceived as a pleasant little residence for one

family. At present, it is overcrowded, dark and rather damp. Probably built in the 19th

century.

46a Nyarogshar Amtchi is a small privately-owned house, and the

owners have made it known that they are thinking of carrying out some necessary repair or

even rebuilding works in the future.

|

| Jangla Shar / Tenkhang Shar, east elevation,

facing Oedepug alley, DJL |

|

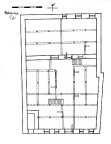

48 Tenkhang Shar - the last remaining part of the historic Ngakhang complex. Ngakhang

was comprised of several buildings and courtyards, and was previously owned by Drepung

monastery. Most parts of Ngakhang were replaced in 1980 and 1990. Tenkhang Shar's long

outside wall and outer corner are important for the southern end of Ödepug street.

Inside, it has few significant details, and can only be accessed through the adjacent

building ‘New Ngakhang’ (which itself was built in around 1980 in acceptable

traditional style). Probably built in the 17-18th century.

49 Lanying Gyap - originally part of a complex of stables and

servants' quarters connected with House no. 36, it was transformed into a separate

residential building in the 1970s.

|

|

Tenkhang Shar,floors 1 and 2,

DJL |

|

L This 1970s residential building has replaced former cow stables attached to House no.

36. Recent shed-type extensions spoil the long courtyard. Just outside the entrance, where the toilets of this buildings and of house no. 36 meet,

lies what can be described as a health hazard zone because of two toilets without

drainage.

6.7 Practical Work 1997-98

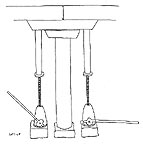

|

| Sketch of Labrang Nyingba northern toilet, JH |

|

The work undertaken and begun by THF in the conservation area includes the

restoration workshop project, water supply improvement, clean-up of rubbish accumulated in

a blind alley, rebuilding and reinforcing of toilets, repair of structural damage, upgrading of toilets, repairing of foundations, repairing and

restoration of facades, putting in new drain pipes, planting of trees, fitting houses with

communal solar-heated showers and actual restoration work.

|

|

Building master Migmar, repairing southern wall of Nagtsagjang

|

THF repair of Labrang Nyingba nothern toilet

|

|

a) Tadongshar: in 1998, the building was restored and upgraded by THF. And this

is also site of the main restoration training programme. Extensive work was done on the

entire structure, the roof was renewed in traditional Arga-style, windows were enlarged, a

solar-heated shower was installed, the toilet was tiled and fitted

with a septic tank.

|

| Sketch map of conservation area Oedepug, JH + THF, DJL |

|

b) Rongda: THF began with the restoration and upgrading of Rongda in late 1998.

The toilet tower of the main building was blocked when a new department store was built in

1993, and could not be emptied out. It was filled 2.5 meters high with excrement, which

caused the walls to bulge outwards, threatening to burst into an adjacent flat's living

room. A way to finally empty the vault was found, and the structure was partially rebuilt

and re-inforced partially. The outbuilding's toilet was also damaged during the

construction of the department store, as was the back wall of adjacent Nagtsagjang house.

The dead alleyway behind those two was filled with debris and construction rubble from

1993, and more recently with household garbage. The mixture was further added to by

contents leaking out from the two damaged toilets. The area was cleaned up, walls and

toilets were repaired, a new drain was built and some trees were planted.

c) Ngakhang: the foundations, which were exposed and damaged when the alley level was

lowered for paving in the late 1980s, have been repaired.

d) Nangmamo: THF has so far completed water supply improvements, toilet emergency

repairs, re-paving of the courtyard, and planting of a tree in the courtyard. Some damage

to the outside wall has been repaired, and an antique wooden gate that was salvaged from

the demolished Liushar house in the Lubu area replaced the modern tin-and-wood gate.

e) Juenpa: lack of proper maintenace of the toilet had caused severe cracks and bulges

in the outlying corner of the complex; part of the structure had to be taken down, rebuilt

and re-inforced.

g) Labrang Nyingba: work has begun to identify urgent problems that need to be taken

care of in order to prevent further structural damage. During 1998 the north toilet tower

was repaired and partly rebuilt. A solar-heated shower was installed in the large toilet

room. Emergency repairs were made to a section of the roof which collapsed during heavy

rains in July 1998.

h) Another blind alley behind Tadongshar house (blocked by the recent construction of a

privately-owned shopping mall) was filled about half a metre high with accumulated

waste; this was emptied.

i) A public toilet was built to ease pressure on the area (see chapter 7),

tree-planting is planned.

|

| Traditional gate, now in Nangmamo House, JH |

|

j) Murunyingba was one of several sites surveyed by volounteer architecture

students of the Chinese University of Hong Kong working in collaboration with THF.

THF has completed water supply improvements, toilet upgrading and courtyard re-paving;

work on this site is on-going.

6.8 Restoration Workshop

THF recruited old master builders with their personal students initially to study the

traditional skills and methods. During 1998, the masters trained a group of younger

construction workers, carpenters and masons. This was achieved by using the somewhat

dilapidated Tadongshar House. Difficult problems were solved by the trainees under

guidance of the masters. Notable feats included the replacing of rotten pillars on the

ground floor without taking the top of the house down, the repair of small areas of damage

in walls without taking the entire wall down, the building of stone walls in the

traditional masonry technique, the making of the traditional long-lasting mud and Arga

surfaces, the replication of the polished black frames around windows

and doors using traditional materials, and the traditonal carpentry work (windows, doors,

pillar-post support). All together, a core group of 100 Tibetans are now being trained and

employed by THF.

|

|

|

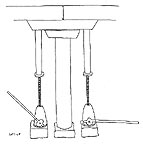

THF workers jacking up a secion of Tadongshar to remove the rotten pillar

|

THF workers preparing to change a rotten pillar on the ground

floor of Tadongshar House

|

sketch illustrating the method commonly used to replace rotten pillars,

using car hydraulics

|

|

|

|

THF mason Loya cutting stones for repair of Magtsagjang wall

|

THF repair of Rongda toilet

|

THF restoration work in Oedepug area

|

|

6.9 Extension of the Programme

Since the initial programme activities carried out by the participants were accepted

and widely regarded as successful by residents and authorities, it was locally proposed to

extend the conservation area to include the entire inner Barkor area. The THF welcomed the

plan and has already extended its activites, including the water and sanitation project,

to cover the entire new Barkor conservation area.