|

| The artist is shown beside one of his traditional style paintings. |

On the streets of Kangding, a high, rugged town on the edge of the Tibetan plateau, are found all the colorful contradictions of developing East Asia: Herdsmen in sheepskin-lined robes saunter past dark-suited businessmen racing to make their next big deal. In the town market, women in long dark dresses, their hair plaited with scarlet strands, bargain with fashionably clad belles who totter seductively on high heels. It wasn't so long ago that caravans of donkeys carried tea through this trading town, which is located in western Sichuan Province but is considered the gateway to Tibet. Now the traffic is motorized, but much remains of Kangding's hurly burly past.

High in a fourth-floor office, above the frenzied clash of old and new on the streets outside, is a man who is trying to bridge the two worlds. In his modestly furnished workroom a soft light flows in from the large window, throwing a glow onto easel and paints. It's morning, and time for Nyima Tsering to begin work.

"I was interested in art from childhood, when my mother took me to see many Buddha images," says the painter, who was born 52 years ago in Batang, a small Tibetan town in southwest Sichuan. "Since then I've traveled everywhere on the Tibetan plateau to study traditional art. I discovered that Tibetan art has stayed the same for centuries. I felt it was time for something new."

He began to study to the artistic traditions of other cultures, acquiring a great admiration for the painters of the Italian renaissance such as Michaelangelo and Rafael. He also studied the history and culture of his own people, and in doing so, felt a growing urge to move beyond Tibet's traditional religious themes, whose style, proportion, and even coloring are rigidly prescribed, and whose subject matter is laden with esoteric--and often inaccessible--symbolism.

His travels over the high, windswept steppe of Tibet taught him something else: of his people's indomitable fortitude in the face of their hostile environment. He soon realized that it was more than material resources that keep them alive. "Generation after generation of Tibetans on the plateau are living on the spiritual. I wanted to express something about how Tibetan people, who live in hard conditions, rely on spiritual resources to survive."

Nyima Tsering's talent won him admission to the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts, where he was able to study nontraditional methods such as oil paints and the airbrush. Then, equipped with new skills and a rich fund of ideas, he set about to invent a new kind of Tibetan art.

|

| The artist is shown beside one of his mixed style paintings. |

The result was a kaleidoscope: old and new mingled in ways that had never been seen before. He took themes from ancient Tibetan thangkas (religious scroll paintings) and revamped them, bringing deities out of their abstract symbol-strewn settings and moving them to surroundings more like the Tibet he knew. To enlarge his subject matter beyond the religious, he drew themes from Tibetan folklore and from daily life. Yaks, for example, had always been thought too humble to be honored as the subject of a painting, but he depicts them in a way that shows their dignity and strength.

His work has won both popular and official support. He was awarded the title of Panchen Master of Painting by the Panchen Lama, Tibet's second most revered religious leader. Now Nyima Tsering's reputation is spreading, and he spends several months a year traveling to promote his work. Exhibited in Japan, Singapore, Algeria, Austria, and France his art has helped to fuel the current fad in paintings of China's minority nationalities.

|

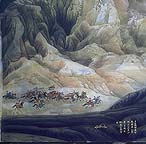

| One of Nyima's mixed style paintings. |

Nyima Tsering sees himself as part of an artistic revolution. "In the West, five hundred years ago there was a transition from entirely religious painting to art that included all kinds of subjects. In Tibet we are just now starting to walk that road." His diverse subjects include religious figures in postures of tranquil meditation, dramatic moonscapes, action-packed hunting scenes, historical figures, and Gesar, Tibet's legendary general and king. His style is surreal and romantic, figures are painted against backgrounds of swirling mist, barren rock, or snowy mountains; and the rules of perspective are, more often than not, neglected turned upside down in order to express his unique vision.

As forward-looking as he is, Nyima Tsering still greatly respects the accomplishments of Tibetan artists of the past, and laments the destruction caused by the Cultural Revolution. But according to him, that wasn't the end of the story, for the present movement to rebuild monasteries has brought its own share of casualties: "Monastery managers don't have a lot of education, so they don't understand the value of the old wall paintings. They regard the murals as an offering. Many [damaged] walls were torn down and completely replaced after the Cultural Revolution, and so the murals were lost."

According to him, what little preservation work is being done in Tibet is reserved for its most famous and sacred shrines, and is being performed by non-Tibetans, a fact that he regrets. He says, "The government has hired experts from Beijing to protect the murals at the Potala Palace and Jokhang Temple, but there are no Tibetans with this kind of skill." Thus Nyima Tsering is extremely proud that his daughter Deshi Yangjing will be among the first trained Tibetan conservators. In a program sponsored by the Hong Kong-based China Exploration & Research Society, she is studying with Italian experts brought to Sichuan to teach conservation techniques.

Although conservation is important, Nyima Tsering says, "To preserve the old is not enough; we need to develop the new. In this way Tibetan art can grow up. If I can develop our art and incorporate outside ideas, I can make a renaissance for Tibetan culture."