A review article by Gary Gach

of the exhibition at

Asian Art Museum

200 Larkin Street, San Francisco, CA 94102, USA

February 21 - May 25, 2014

Some ideas seem so obvious, so simple, one wonders why they’d never been expressed before. So it is with this landmark exhibition: Yoga: The Art of Transformation.

It might have come to its curator, Debra Diamond, PhD DD, in the blink of an eye, yet it took half a decade to bring to light. Along the way, yoga studies have become one of the fastest-growing fields of South Indian research -- during which time she enlisted over a dozen diverse scholars as allies. The works she’s assembled, from 25 collections, furnish an amazing window onto yoga, in all its ever-evolving layers and potencies. And, as with any good equation, the premise is reversible: yoga serves as a marvelous lens for touring the vast civilization of India. What’s fresh is this first-ever use of visual culture as our guide.

Possibly the most common western conception of yoga is of a yoking of the individual and godhead … the supreme identity of selfhood (atman) and the Absolute (Brahman) … Tat Tvam Asi (Thou Art That). This core premise is shown here in diverse depictions of the universe mapped on a human body.

But, at the outset of the exhibition, three statues remind that yoga is a confluence of branching streams, such as Brahmanic, Buddhist, and Jain. So, considering yoga’s “history,” we might substitute “histories.” And the eternal truth of yoga has multiple meanings.

Nearby, is a triptych by Bulaki, from the Nath Charit (1823). As it’s from an esoteric tradition, we can only interpret what we see without its accompanying secret verbal material, which might point to a parallel but different meaning. [1]. It seems to present the transcendent dimension, consciousness, and the material realm; reading this formula right-to-left, it’s a map for practice. A saffron-cloaked, ash-smeared adept sits on the bare ground -- matter (represented by tin alloy meticulously incised in an overlapping circular pattern) -- which rises up, like a mountain or wave, the peak seeming to converge with the head of the noble, upright yogi. Then, the ground‘s fallen completely away, as he sits without horizon. Next, limitless space … pure spirit … the Source. Liberation (moksha) from human suffering. Nirvana.

It’s a remarkable revealing of the ineffable. Of course, there are prior instances, such as of Buddha (Enlightenment) as footprints. And, further east, Kuòān Shīyuǎn rendered the imageless ultimate, in his sequence of ten oxherding pictures (no seeker, no ox) -- but not with such compelling virtuosity, responsive to one’s gaze, in the luminosity of gold leaf, shimmering.

The work is also representative of the show’s ability to provoke questions. For instance, normally, do I ever see light itself? Or, only as refracted and reflected? Likewise, how does one see enlightenment?

Overcoming human suffering requires wisdom (prajna). Also, power. The primal power of the cosmos, shakti, is feminine; yoga enables it’s “perfection” for supernatural power siddhi as well as spiritual. It’s evident in three life-sized stone yoginis. Their familiar voluptuousness equals auspiciousness, making everything fertile. Yet, looking closer, we note hair wild from flying in the night. And there’s a transgressive ferocity latent in their siddhi power. That cup – it’s made of a human skull, from which she drinks blood or liquor. These three also represent, here, the hordes of goddesses emergent in yoga art from the 9th-13th centuries, each with unique name and attributes.

Spiritual power typically influences a state, as well as its individuals. The wandering Nath sect, for instance, who crafted hatha yoga, later converted the ruler of the desert kingdom of Jodhpur kingdom, and took over its administrative posts.

This theme is visually striking in two renditions of South Asian magical realism within political contexts. In one watercolor, a yogi conjures a storm, drowning a king’s enemies.

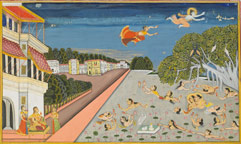

In a subtler one, the scene is set at a king’s royal grounds, extending in quasi western perspective as far as to the horizon -- but the charm is all in the vertical dimension. Courtiers (like us all) play half-in half-out of the waters of materialism; one of whom is unseen but for an uplifted hand. Majestic birds rest on the pond and on the nearby tree, which bathes branches in the pond and also aspires to the sky. Up there, in a lapis lazuli sea of sky, glides yogi Jallandharnath, as Princess Padmini seems to swim after him.

Even the gods themselves practice yoga, as attested to by the 13th-century bronze Vishnu, seated in his fierce, majestic, graceful man-lion incarnation as Narashimyha -- a yogapatta strap around his knees, stabilizing his body so he can forget it and become fully absorbed in meditation. His perfectly poised symmetry is further echoed by a splendid standing bronze Jina (1000-1100), both figures also exemplifying the equanimity of the divine ideal (transcendent, because none of us are so symmetrical). In this regard, the sleek, stylized, sublime, Jain sculptures are particular stand-outs.

Also from the Nath Chalit, a triptych makes pictorial another invisible valuable: spiritual transmission. What’s transmitted, from monastic teachers to disciples, and disciples to wider followers, is up to each viewer’s own understanding of attainment, and lineage. Still, we all can see it as illustration of intersubjectivity, the harmony of people sharing common principles. It reminds too of yoga’s power to build community.

Further along, we see pages of Bahr al-hayat (Ocean of Life), 1600-1604, the first illustrated manual for yoga asanas, traditionally taught only by a guru, face-to-face. Commissioned by Prince Salim (the future Mughal Emperor Jahangir), in Allahabad, (where the Ganges meets the Yamuna, near Kumbh Mela) -- this album further reflects yoga’s multicultural influences. Consider the page for the Nauli Kriya yoga pose. The artist, Govardian, subtly uses a deft shadow on one side of the yogi’s torso to indicate the yogi is isolating and revolving his stomach muscles. And the yogi’s face: what a beatific expression! Such a gaze, along with tousled hair and beard, is a tip-off we’re seeing Christ as yogi -- as inspired through images in circulation via missionaries. Drawn from Sanskrit texts and interviews with contemporary Hindu yogis, the Persian text was composed by Sufi master Muhammad Ghwath Gwaliori, consonant with his goal of empowering his followers on the path of transformation.

Watercolor landscapes of monasteries and pilgrimages guide us across further potentialities of yoga and its meanings. And, taking landscape as internal as well geographical, listening stations provide opportunity to match up images of particular rasas (moods/tastes) with ragas (musical modes) associated with them. (Topic for curators hence: yoga and Indian dance.)

Did you know? yoga is now practiced by 20 million Americans -- and spells a $10 billion annual industry. What happens when the path of yoga, leading to the greatest good, intersects America’s culture of the greatest goods? Here too Yoga presents key topics for consideration, these spanning nadir to zenith, in media appropriate to our postmodern milieu.

Expanding on the asceticism glimpsed earlier in a striking sculpture of the fasting Buddha -- postcard photography introduce former forest dwellers performing feats of physical transcendence, both fantasy and actual. A circus poster advertises Koringa, who claimed to be “The Only Female Fakir in the World,” taming cobras and crocodiles. But that’s not all.

On a wall of the final room, Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, ancestor of contemporary yoga, performs a series of asanas, recorded in 1938. (At 50, he looks 30.) Across from him, Swami Vivekananda gazes out from the Parliament of World Religions, Chicago (1893), the first living Hindu seen in the West. The tribute to Vivekananda includes an early edition of his Raja Yoga (first published in 1896), aimed at rectifying the view of yoga as simply physical asanas; in so doing, he helped craft a secular iteration for export. (Yet didn’t Patanjali himself design a more simplified map of yoga than then current?)

The San Francisco leg of the tour adds a commission by local desi artist Chiraag Bhakta, entitled #WhitePeopleDoingYoga. This 13x30' wall of ephemera from his personal collection of book covers, ads, album art, etc., incites further questions, drenching the viewer in the contradictions of yoga as ego, as orientalism as spiritual materialism.

As we saw at outset, so too at the close: there’s no single “yoga,” but rather a spectrum, itself in transformation –spanning, today, from specious physical fitness fetishists, to informed devotees grounded in living tradition. We cannot even really call yoga eastern anymore, since Euro-American kids have now been raised in households of practitioners. Indeed, the show makes clear yoga’s viability as capable of transcending any concept of itself.

And the story continues. Mounting the exhibit in California has placed it one of yoga’s international meccas. The California Yoga Teachers Association, for instance, founded Yoga Journal in 1975: today, its pages reach nearly two million subscribers, near and far.

From June 22 to September 7, Yoga makes pilgrimage to the Cleveland Museum of Art, (sometimes called “the buckle of the bible belt”), to enlighten newcomer and adept alike. An idea whose time has come, its influence will long continue to ripple, with the splendid vitality of its Source.

© 2014 Gary Gach