The Loom of Culture

Asian Art Museum. San Francisco

December 17, 2021 – May 2, 2022

by Gary Gach

all text & images © Asianart.com and The Asian Art Museum except as where otherwise noted

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

When we appreciate a work of pictorial art, Eastern or Western, it can be said we are deeply reading it – not unlike closely reading a written text. For example, regarding a landscape, it might give us pause to enjoy the atmospheric spaciousness of sky implied by a horizon placed low. Such invaluable senses of appreciative discernment are activated on many levels in the current exhibition at the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco: Weaving Stories. An initial question here might be how do we read textiles?

Presenting the exhibit, Director Jay Xu introduces to this realm with a sharp d’art from our everyday, lived world. “With the ongoing pandemic,” he said, “we see how our reliance on textiles to relate to the world around us has shifted – with masks, just a tiny piece of cloth, protecting us and signaling our respect for the well-being of others.”

Our appetite for this major selection from the Museum’s textile collection had already been whetted by a 2013 showing there of 16 Javanese batiks, from the collection of Joan and M. Glenn Vinson, Jr. – Weaving Stories now presents over 40 outstanding examples of textiles and garments from island Southeast Asia – that is, from across 10 islands of Indonesia as well as from the Philippines and Malaysia.

Whenever a gifted curator has a chance to go to work on an extensive body of work, the results can be marvelous. Associate Curator of Southeast Asian Art Natasha Reichle has drawn from the Museum’s collection of 263 Southeast Asian textiles (220 from Indonesia, 15 from Malaysia, and 28 from the Philippines), in a presentation that is vibrantly diligent, exquisitely multidimensional, and immeasurably inspiring.

Narrative Art

Ceremonial textile (tampan)

Two textiles stand out as to literal story-telling. Both concern the sea, which simultaneously separates and joins communities across Island Southeast Asia. Consider the 18th-century ceremonial tampan from Indonesia on display. Square tampan textiles (“ship cloths”) are unique to the Lampung region of southern Sumatra, wealthy for being well-positioned on the Spice Route. They might serve as covers for gifts, seats for visitors, or an object of ritual exchange, and could be used in a range of life ceremonies, from birth to marriage to death, plus events inbetween. There are two primary styles, tampan from the interior with large zoomorphic motifs such as giant hornbills, and those of the coast distinguished by very fine detailed weaving of a ship with ancestors. Interior tampans might be found in many homes, but the very fine coastal variety as seen here would be found in a home of nobility. We also note its stylized depiction of ancestors as bearing resemblance to wayang shadow puppets.

Two centuries later, Milla Sungkar applied her Javanese batik artistry to a textile commemoration of the 2004 tsunami in Aceh – where, alas, upwards of a quarter of a million lives in several countries were suddenly destroyed. While, before our eyes, all else is, becoming engulfed in pandemonium – anchoring her vivid retelling of the tragedy is the presence of the Mesjid Raya Baiturrahman mosque, off on the horizon, one of the few structures to survive.

Yet we can, as they say, “drop the story line” to go deeper. The charm here is how many varied kinds of story which fabric can tell, when looked at with care. Indeed, part of what makes Weaving Stories so fascinating is the greater story of what it means to be human – underpinning the gorgeous artifacts – a story told on multiple levels across various layers that all mesh.

Materials

As a survey exhibit, Weaving Stories naturally covers a range of materials and methods. Although the works are all under glass, the Museum provides booklets with fabric samples for fingers to feel. Beside cotton, linen, and silk, on view are bark, banana fiber (abaca), and pineapple (piña). The dark, heavy bark of ficus trees made textile that would last a half a year. Cloth made from lighter, mulberry bark, seen here in a woman’s blouse (lemba), might last a week, and was reserved for special occasions. Pineapple had been brought to the Philippines by Spanish colonizers in the 1500s. As substance for fabric, it has a delicate, gossamer-fine feel. Materials can also be added to fabric, as in a blouse from the Philippines (albong takmun) decorated with hand-cut seashell sequins. The fabric is abaca, a species of banana whose fibers are extracted, cleaned, sorted, and softened. Then, after dying, the threads are individually hand-tied together.

Woman's blouse (lemba) |

Woman’s blouse (camisa) |

Woman’s blouse (albong takmun) |

Methods – & More

Woman’s skirt (tapis) Three basic weaving techniques are songket, and ikat, and batik. In a songket, supplementary wefts (cross-wise threads), often made of metal-wrapped thread, are introduced by the weaver as she builds up her cloth on the loom. The Museum furnishes a special magnifying device for closer looks at two such brocades. Here, we see a woman’s skirt (tapis) by Abung weavers of Indonesia. [Note: songket is often confused with sungkit, discontinuous supplementary weft wrapping technique used to great effect by the Iban of Borno, also on view in the exhibit.]

At this point, we might pause to note how – along with narrative imagery and the production of materials – we’ve begun coming upon deeper stories – opening onto themes of community and the cosmos – which amplify themselves the further into the exhibit we go.

In an ikat, threads are tie-died before being woven into cloth. The tied threads are thus protected from dye. Repeating the process creates further patterns. The exhibit’s first example of ikat is a funerary shroud or banner (sekomandi). Its pattern of hooks and arrows represent generations of ancestors. Foreground and background command the eye equally, the dynamic heightened by the pattern’s contrasting colors of red and blue.

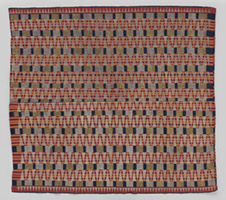

A nobleman’s skirt cloth (bidak) from Lampung evidences another demanding technique – weft ikat. This requires the threads to be aligned with each pass of the shuttle, and the shifting pattern here is hypnotic.

Later on, we see a ceremonial cloth (pua kumbu) made by Iban women of Borneo. Pua can be used to line the walls of a longhouse, cover shrines, and lie beneath offerings. They connect the human realm and the realm of the ancestors and gods. Here, the skill at intricately patterning the ikat is eclipsed by the weaver’s ability at preparing the mordants (fixatives that bind color to thread) and ability to dye (with the grasp of botany and chemistry that implies).

This also touches upon how status could be conferred upon weavers. Scholar Traude Gavin notes such a weaver’s accomplishment is equivalent to the status of a man leading a headhunting party. The wall label continues with a glimpse of an even larger story: “Both activities were seen as inherently dangerous and requiring help from the spiritual world. The origin myths of the Iban mention woven cloth, and weavers are still said to be visited in their dreams by legendary sisters who show women patterns to weave.”

In batik, molten beeswax is drawn and/or stamped onto fabric. It is then is steeped in dye, for days or even months. After the dye bath, the wax is removed from the cloth, by boiling or scraping, revealing where dye saturation has been prevented from dying the cloth. This is done on both sides of the cloth, and the process can be repeated up to four or five times, or even more, depending on how many colors are desired.

The first batik in the exhibit is quite amazing. From a distance the eye is drawn in by its deep, dark indigo. Move closer, and fine patterns appear on the hand-spun cloth – a landscape of buildings and gardens, with disembodied wings floating amid trees and vines. Look deeper. Other designs emerge: plants transforming into abstract flying birds, or curious long-trunked creatures. This type of landscape motif is called semen in Javanese, derived from semi, to sprout. The wings are said to represent the wings of Garuda, Hindu divinity that has remained long after the region’s widespread conversion to Islam.

Archival Photography

Space doesn’t permit dwelling further on the specimens shown in this exhibit. Besides, even if we took another 40 years, we’d still be scratching the surface. Nevertheless, just one more item deserves mention: archival photography. Within the exhibit are two movies of Colonial-era photographs showing garments being folded, tucked, died, draped, and worn. Factoring in how they may often be staged, and exploitative, they also serve as transformative expressions of cultural memory. Archival Photos.

Weaving Stories affirms how any community manifests culture. Here in the U.S., I see young women wearing denim torn and slashed. Well, that’s one example of clothing as indicator of gender, age, and status – albeit within a disjointed cultural dislocation. (Who was it who said fashion is the race to look like everybody else?) The community that it reflects is a mass culture of entertainments, a mall of commercial attractions. Weaving Stories invites our consideration of culture as telling stories about our human universe in far more radical, interconnected, coherent ways. (There’s no catalog so, if you can, don’t miss it. Otherwise, please check out our bibliography, below.)

Gary Gach is a teacher, author, and literary translator. His most recent title is Pause … Breathe … Smile (Sounds True; Tantor Media, audio edition). His previous book is The Complete Idiot's Guide to Buddhism. He also edited What Book!? – Buddha Poems from Beat to Hiphop. His work has been published in American Cinematographer, Art Week, The Atlantic, Harvard Divinity Bulletin, Kyoto Journal, Mānoa, The New Yorker, and Yoga Journal.

Author page: GaryGach.com

For Further Reading

Barnes, Ruth and Hunt Kahlenberg, Mary, editors. Five Centuries of Indonesian Textiles. (Prestel. 2010).

Gavin, Traude. Iban Ritual Textiles. (NUS Press. 2004).

Murray, Thomas. Textiles of Indonesia. (Prestel. 2022).

Vinson, Joan Claire and Glenn M. The Vinson Collection of Indonesian Textiles. (Privately Printed Limited Edition. 2021).

Contact <Shop@AsianArt.com> for ordering information.

This Reviewer gratefully acknowledges Thomas Murray for his insights and suggestions about Indonesian textiles in preparation of this coverage.

Archival Photos

Back to main exhibition

asianart.com | exhibitions