|

Curator's Preface

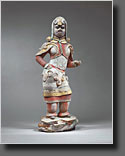

The seeds for this exhibition were sown several years ago when Peter Scheinman, chairman of the Asian Subcommittee of the Harvard University Art Museums' Collection Committee, arranged for me to meet Anthony M. Solomon and to see his collection of Chinese funerary sculptures. Having heard about Tony Solomon's collection for at least a year before that meeting, I was prepared to see something special; nevertheless, I found the collection completely overwhelming-its quality, chronological breadth, and closely defined focus well beyond anything I could have imagined. So discerning has Tony been in assembling his collection that no verbal description could begin to prepare one for the very satisfying aesthetic and intellectual experience of viewing it, as I quickly discovered! Associated in traditional (and even present-day) China with death and burial, rather than with art, and almost unknown outside China before the late nineteenth century, Chinese ceramic funerary sculptures came to world attention over the course of the twentieth century, brought to light by chance discovery and controlled excavation alike. By this time, virtually everyone interested in art recognizes Tang horses and camels, and the life-sized terracotta warriors from the trenches surrounding the tomb of Qin Shi Huangdi (r. 221-210 B.C.), the first emperor of the Qin dynasty (221-206 B.C.). Most collectors of Chinese tomb sculptures have specialized in the brilliantly colored sancai, or "three-color," glazed examples from the Tang dynasty (618-907). By contrast, Tony Solomon has taken a much more comprehensive view, acquiring funerary sculptures from the Han (206 B.C.-A.D. 220) through the Tang dynasties. The collection is especially strong in sculptures from the sixth century. Avoiding the road already well traveled, Tony focused on unglazed pieces that were embellished with mineral pigments after firing, a technique known as "cold painting," though his collection includes distinguished glazed pieces as well. A sculptor himself, Tony realized that unglazed sculptures, lacking brilliant color, are the best vehicles for conveying the power of pure sculptural form; he also recognized that cold-painted ceramic sculptures best reflect the sculptors' achievements in naturalistic description, since the artists were better able to capture realistic details with the broad palette of mineral colors than with the limited range of bright colors afforded by the glazed tradition.

From earliest times, the reasons for provisioning tombs with burial goods were four: to provide food, water, and wine to sustain the spirit of the deceased in the next life; to provide a variety of humans and animals to serve, entertain, and amuse the deceased; to provide guardians to protect the corpse and the spirit of the deceased on its journey to the next world, not to mention to protect the tomb itself from invasion, desecration, and robbery; and to provide a sufficiently great quantity of food, sculptures, and luxury and other burial goods to establish beyond all doubt the wealth, importance, and elevated status of the deceased-whatever his or her actual status in the temporal world might have been-so that he or she would not only repose in glory but be appropriately received in the next world. During the Neolithic period, provisioning of the grave with food and drink seems to have been of paramount concern. However, by the Shang dynasty (c. 16th century B.C.-c. 1050 B.C.), the other functions were rapidly ascending in importance. With its thousands of life-sized horses and armor-clad warriors, the so-called terracotta army buried around the monumental tomb of Qin Shi Huangdi, the founding emperor of the short-lived Qin dynasty, reflects an early preoccupation with protecting the tomb from demons, evil spirits, and human intruders. Already in Neolithic

times, graves had been furnished with vessels filled with grain, water,

and wine to nourish the spirit of the deceased. By the Shang and Zhou

(c. 1050-221 B.C.) dynasties, elaborate funerary ceremonies had evolved

that required the use of jade implements and ritual bronze vessels.

Shang ceremonies sometimes involved human and animal sacrifices as well,

the animals including elephants, rhinoceroses, horses, oxen, pigs, and

dogs, among many others. Burial figurines of wood were used in the south

during the Warring States period (481-221 B.C.), perhaps as substitutes

for the sacrificial victims of earlier times. Then, burial sculptures

of fired ceramic ware began to be used in the north from the late third

century B.C. onward.

The earliest ceramic tomb sculptures-those of the Qin and Han dynasties-represent warriors and horses. Intended to protect the tomb from demons and intruders while at the same time symbolizing the wealth, political power, and military might of the tomb occupant, they depict ethnically Chinese figures in native attire. The repertory of subjects expanded during the Han dynasty to include court attendants, entertainers, and barnyard animals. By the sixth century, not only had the range of subject matter expanded further still, but it reflected influences from India, Persia, and Central Asia that reached China via the Silk Route. Those influences manifest themselves most forcefully in the foreign faces and clothing styles of the guardians, merchants, and grooms represented-a cosmopolitanism that culminated in the exceptionally naturalistic sculptures from the Tang dynasty. From Court to Caravan, the title of this exhibition and catalogue, speaks to the range of subjects encountered among Chinese funerary sculptures, just as it suggests something of the interaction between native Chinese traditions and the foreign goods and concepts newly introduced via caravans plying the Silk Route: from Chinese court officials and attendants to foreign warriors and guardian figures, from Chinese musicians and entertainers to foreign merchants and grooms, from native dogs and boars to Arabian horses and Bactrian camels. During the Tang dynasty, China was the undisputed leader of the world, and her capital, Chang'an (present-day Xi'an), the world's largest, richest, most cosmopolitan city. As a wealthy, sophisticated metropolis and as the eastern terminus of the Silk Route-even if numerous foreign goods, including luxury items, did find their way further eastward to Korea and Japan-Chang'an was a magnet for a multitude of non-Chinese visitors, traders, and religious mendicants. Chang'an had not only great Buddhist temples and monasteries but sizable communities of Muslims, Jews, and Nestorian Christians as well, adding to the religious and intellectual fervor of the day. Major changes in burial customs after the Tang dynasty led to a significant decrease in the use of funerary sculptures. That is, after the Tang dynasty, the Chinese began to burn paper replicas of the goods they wished to offer the deceased in the belief that the smoke from the burnt offering would convey to the next world the essence of the image burned, whether a horse, guardian warrior, or gold ingot-or, in contemporary times, a Mercedes, refrigerator, cell phone, or satchel brimming with "play money." Thus, what had been a major tradition for more than a thousand years suddenly became a minor tradition after the fall of Tang, with a commensurate decrease in the later sculptures' artistic vitality. The long period from the Han through the Tang thus represents the "Golden Age" of the Chinese funerary sculpture tradition-precisely the period on which Tony Solomon has focused his collecting activities.

|