Emperor Jahangir, fiercely passionate about painting and wholly dedicated to imperial patronage of individual masters perfecting the refined Mughal style, bestowed the title Nadir ul-asr on one of his favorite artists, Mansur, calling the painter of flora and fauna “Wonder of the Age”. Traveling amongst the keenly observed leaves and veins of foreground vegetation, through soft earth undulating with vivid naturalism, along the elegant lines of Mansur’s painting of a nilgai (“blue bull”; ca. 1610-15), and plunging deep into the startling lucidity of the animal’s shimmering eye, it is easy to comprehend Jahangir’s devotion.

Even as scientific realism ceded to lush idealism, as Shah Jahan (reigned 1628-58) inherited his father’s studio of artists and reimagined naturalistic Mughal style as sparkling Shangri-la, fervent patronage of the arts endured, passing from one ruler to the next. Both dynamic aesthetic reinvention and the mighty nexus of imperial collectors’ ardor are abundantly evident in A blackbuck - left (Mughal; ca. 1650), a sumptuous watercolor featured in the exhibition, “In the Realm of Gods and Kings: Arts of India”, running from September 14, 2004- January 2, 2005 at the Asia Society in New York City.

While Jahangir’s sensitive eye favored the artistic candor of minutely detailed nature, Asia Society’s blackbuck speaks of Shah Jahan’s elaborately constructed paradise, a collector’s eccentric passion realized by a stable of artists and sustained by extraordinary power and wealth—a perfected world created to consummate a patron’s personal vision. Draped in necklaces of pearls, red silk tassels and shells, this is not a proud wild animal but rather a docile pet enthroned on a manicured island of grass, graphic and weedless, the details of cherished domestication at play in the gentle set of its mouth, tame eye, and dreamlike twisting of horns under billowing fists of pink, crimson, plum, and gold clouds—a sumptuous sky styled more on the patterned awning for a royal ceremony than on nature.

As emperors established and nurtured studios, cultivated public taste in the image of personal taste, and created enduring visual legacies of their rule, it can truly be said that the vitality of the arts waxed or waned with the passion of kings. Aspects of this centuries old tradition of artistic patronage live on in the modern collector, who funds both individual art purchases and lavish exhibitions, gathering works under distinctive umbrellas of affinity and appetite, discretion and pleasure.

Anchored primarily by the collection of Cynthia and Leon Polsky, supplemented with loans from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “In the Realm of Gods and Kings” is a study in eclecticism, encompassing brush drawings, ivory plaques, combs, and sculpture, Mughal, Deccan, and Rajasthani paintings, jarringly anachronistic contemporary photography, a pair of 11th-12th century book covers for a Buddhist text, Bidri ware, and even a silk embroidered tent lining.

As Shah Jahan engineered his reality, directing artists to render populations elevated to utopia, inhabiting paradisal gardens and Arcadian mansions—editing out life’s darkest corners and even the unremitting filial violence that would engulf and eventually devour the ruler, two of his sons, grandson, and great grandsons (all of whom perished at the hands of Shah Jahan’s brutal third son, Aurangzeb) in the 1657-58 War of Succession—so Ms. Polsky crafts her reality in these starkly perilous times, assembling a fantastical alternate world of Hindu gods and demons, mythological realms bound by a sensual thread that, for a few lustrous hours, transports the viewer to her own chaitya, or shrine, a place of reverence.

Eroticized with a fully nude Radha clasping a transparent garment to her breast after lovemaking, the painting Krishna and Radha on a bed at night - right (Sirmur (nahan), Punjab Hills; ca. 1830) is a jewel box of sensuality, from the seductively muted palette and deft interplay of lush tonalities to the pale magnet of lovers set against a starry night. Thematic elements serve both to mirror their passion and underscore the almost suffocating luxury of their surroundings—solitary candles, each set in a gold candlestick, burn as beacons under green, purple, and yellow domes, as gilded birds in cages. The mood of hyper exoticism embodies all the pleasures conjured by the Western mind when it dreams of Eastern lust; chaste shards of English high tea cups hijacked by Indian sensuality—framing a scene utterly foreign and forbidden.

Even the pristine solidity of ivory and rather formal poses cannot quell the fundamental carnality of the Sculpture of a loving couple - left (Madurai, South India; Nayak period, 17th century), an enigmatic depiction of royal, secular, or possibly epic (perhaps Rama and Sita) love. Despite the mass implied by highly stylized bulging eyes and rounded, fleshy appendages, the sculpture’s center of gravity is oddly off, setting the couple swaying to the internal mechanism of unseen emotions.

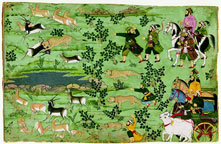

Turning away from the human element to confront nature, Ms. Polsky’s collection endeavors to remain in Eden. While the exhibition features a select group of hunting scenes in paintings illustrating the gamargh, or mass slaughter of wild animals within a small enclosure (Shah Jahan hunting blackbuck with cheetahs - below (Udaipur, Rajasthan; ca. 1710-15) depicts five doomed blackbuck, one awash in blood, its head grotesquely twisted by a cheetah), the majority of animals luxuriate in ravishing ornament, bordered by resplendent vegetation and exquisite organic abstraction.

|

Two anthropomorphized monkeys, one clenching and eating

a banana and the other gently grasping a flower, appear far more human

than primate as flickering internal life animates a meticulously carved

Bracket with a monkey, parrots, and scrolling leaves - right

(Nayak period, first half of 17th century; South India). A diminutive

version of brackets surmounting stone columns in edifices constructed

under Nayak patronage, this piece is a brilliant study of the animal psyche,

supplanting the existentially empty bestial vessels of western art with

the simian individuality of a mischievous smirk countering wise contentment—contrasted

sharply by parrots carved in low relief, purely graphic elements which

barely emerge from the ivory.