POWER AND GLORY MAIN EXHIBITION | INTRODUCTION | CATALOGUE

REVIEW by Gary Gach

Here’s a groundbreaker. But first, a peek behind the scenes. In 2000, when the Asian Art Museum was still in Golden Gate Park, each curatorial area was planning its first major exhibition for the new building, across from City Hall. (Thus far, the new Asian Art Museum has presented a definitive survey of the Goryo dynasty, a landmark exhibition from Thailand, a powerful show of Rajasthani art, and a memorable two-part survey of Kyoto eccentrics, not to mention a stunning spotlight on the Museum’s unparalleled bamboo art collection, from the Lloyd Cotsen Collection).

Michael Knight, senior curator of Chinese art and deputy director of strategic programs and partnerships, recalls their goal was “to find something that would be spectacular, popular with a broad audience, fundable, and a significant contribution to Chinese art history.” With curator Li He, he subsequently learned Beijing would be hosting the summer 2008 Olympics, with which Museum founder Avery Brundage had been associated as President of the International Olympics Committee, 1952–1972. So with the eyes of the world on China, what would best reflect the splendor of this millennial civilization, and the powerful position China has now rightfully earned in the comity of world nations?

The Ming influence, already known to collectors, asserted its atmosphere. Joining flags in presentation are five museums: The Palace Museum (Forbidden City) in Beijing as official partner as well as source of art; the Shanghai Museum (San Francisco’s sister city) for its Ming paintings; and the Nanjing Museum and the Nanjing Municipal Museum (never before tapped for any major U.S. exhibition, yet site of the secondary capital of the Ming) for archeological discoveries. Plus, the Asian Art Museum drew from its own Ming lacquers and ceramics from the Brundage core collection there.

Thus was born Power and Glory: Court Arts of China’s Ming Dynasty. The first major exhibition to survey the full range of Ming imperial arts, its 240 selections include porcelain paintings, textiles, lacquer, jade, jewelry, architectural elements, and so on. The result is an unprecedented view of the art of the imperial court, traditionally looked down upon by the literati. The unrivalled scope and refinement the cultural achievements is broken out at the Asian Museum into seven themes related to Ming court life: governance and hierarchy; entertainment and hobbies; daily life; architecture and court environments; technology and innovation; religion and beliefs; and education and tradition. Here follows a partial checklist of a few highlights of a sweeping panorama.

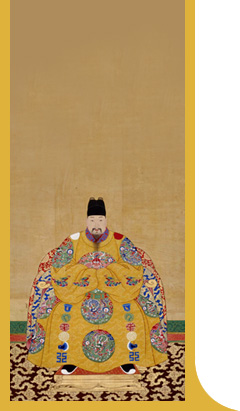

The imperial robes on view are quite persuasive that the mandate of no less than Heaven was deemed necessary for the legitimization to rule the Middle Kingdom. A sovereign yellow silk dragon robe on display here has never been seen before, anywhere: discovered by curator Li He at the Palace Museum, stored in its original box and never sewn together, its pristine condition alone doubles its breathtaking majesty. Similarly a first is an amazing crown ornament: an amber heart, signifying loyalty, flanked by gold dragons amidst whirling clouds inlaid with ruby. Rivalling them in elegance and technical mastery are the belt ornaments of white jade.

Power and Glory aptly imparts a sense of the palatial Ming treasure ships, sent forth as far as Africa. Commercial trade being beneath the emperor, their aim was to bestow gifts and bring home tribute. Thus did Chinese porcelain gain such renown as to rival and replace silk, as evidenced by the remarkable blue-and-whites, and other delights.

Earthenware segments of an arched gate reflects new foreign influences: imagine an elephant with Chinese eyes, for instance. And in Wu Bin’s painting of Buddhist deity Samanthabhadra, he’s shown with his traditional elephant. The painter, never having actually seen an elephant, had to surmise how it might recline, so it’s kneeling forward, front feet demurely folded below its trunk. Moreover, the deity’s attendants each seems to portray a different ethnicity.

Of the textiles, two other stand-outs are religious-themed. A suite depicting Guan Yin and eighteen luohans is a virtuosi display of guxin, the embroidery art of the Gu family, with pale ink or light color washes enhancing the embroidery’s painterly mastery. Breathtaking is the thangka of Raktayamari, the Red Conquerer of Death, a wrathful form of Manjushri, shown with his consort, trampling a god of egoism. The tip of a tassle of his sword swirls out into a field of myriad luminous flames, as do fringes of his garment. Colossal, it spans from museum floor to ceiling — and without its original matting. Its vibrancy of pristine preservation is due in part to the dry climate of Tibet.

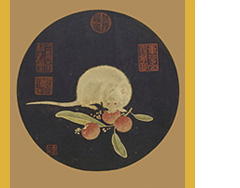

Ming landscape paintings often hearken back to Tang and Sung achievements, and a goodly array are on view. One pair of paintings depict panoramas of the refined pleasures of courtly dignity. Men indulge in wei-chi (Chinese chess; Japanese, “go”), calligraphy, and music; women pose for portraits, play with a doll, listen to a music recital, drowse, play golf, put on make up, etc. All in elegant attire. A painting of a woman dipping her hands in a bowl of water in which the moon is reflected sums up the magic of this exhibition, the Ming atmosphere still suffusing our world today like the rarest flower.

Costliest exhibition of the Museum’s history, a substantial portion was underwritten by the new Robert H.N. Ho Foundation. The week of the exhibition's opening, Stanford announced its large gift from the Foundation, to foster graduate Buddhist studies and endow a Ho Center for Buddhist Studies center, the first in a proposed network of such scholarly Dharma centers. Clearly this is a 21st century institution to follow keenly. And the show marks the incumbency of a new museum director. With the retirement of Emily Sano, after fifteen years of service, Jay Jie Xu (“shu”) takes the reigns just in time for this Ming pageant.

Power and Glory will be on view in San Francisco through September 2008, then traveling to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, October 2008 – January 2009, and capping its run at the Saint Louis Art Museum, February – May 2009. The indispensable 280-page catalog includes an introduction by Michael Knight and essays on gold, jade, ceramics, metal, and cloissoné, by Hi Le; on textiles and costumes by Terese Tse Bartholomew; on lacquer, wood, and bamboo by Michael Knight, and on paintings by Richard Vinograd. The book also inaugurates a new, exclusive, international distribution deal with Tuttle Publishing for the Museum’s publications.