|

High

Altitude and The Art of Watercolour

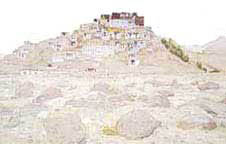

The Himalayan Kingdoms are magnificent, awe-inspiring, endless, arid, terrifying, serene and closer, it seems, to some sense of the spiritual world amidst the mountains, the green valleys, the high altitude deserts than the hustle and bustle, the ease, perhaps, of life at lower altitudes. For centuries many of these lands have been closed to foreigners. Even now they can be dangerous for the unwary: these are places and people that must be treated with respect. Tourism is encroaching, visitors do leave more than footprints; but at the end of the twentieth century, Ladakh remains perhaps the most traditional, the least touched of all the Himalayan provinces, having only been open to foreign visitors since 1974. Change is coming although the pace is variable. Inspite of the harshness of the terrain, the strategic importance of the area has led to unbelievable feats of engineering: the two roads to Leh, from Srinigar on the one hand (at present closed to tourists) and from Manali and the Kulu Valley on the other, were both built at the cost of men's lives. Improved communications have opened up Ladakh to tourism in the summer months and still more roads are under construction. One of these, the Kardung La road is, at over 18,000 feet, the highest motorable pass in the world.

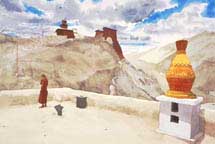

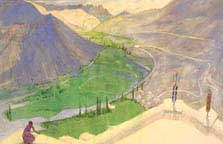

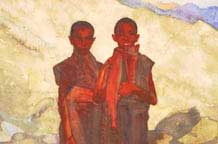

The mountains are landscape - and they are a state of mind. Perhaps nowhere more so than in Ladakh, the high plateau sited between the northern Karakorum and in the rain shadow of the Great Himalaya. La means mountain pass, Ladakh is the land of the mountain passes and was once part of the great trade routes that criss-crossed the mountains of India, China and Tibet. Still often referred to as Little Tibet, it is now in Ladakh more than in Tibet that Tibetan Buddhism is openly practised. Yet Ladakh is not merely a spin-off of Tibet; it has its own distinct and vibrant culture, including a sizeable Muslim component among its small population. The brilliant colours of Ladakh are in the sky: the landscape is ochre and stone and white and a myriad of soft colours, dry and bleached in the wind and the cold, yet peculiarly reminiscent of the shores of a vast and long gone inland sea. The blood-red of the monks' robes, enlivened with flashes of orange, the great gilded statues of the Buddha, the prayer flags, the hints of colour in costume and the extraordinary, vivid sand paintings or mandalas are occasionally brilliant, as are the splashes and patches of green fields by the grey-blue Indus and its tributaries.

The Himalayas are a series of mountain ranges, mountains among mountains and ranged among mountains. To the west are the Pamirs, the Hindu Kush and the Karakorum whilst further east, amongst the Great Himalaya, are the old kingdoms of Ladakh, Kashmir, Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim. These lands, containing among them the highest mountains in the world, are home to myths, to animistic beliefs, to millennia of Buddhism, and to tenacious life: to the elusive snow leopard, to yak and dzo (that cross-breed between yak and cow), to barley fields, to the beautiful and unexpected mountain rose.

In the nineteenth century, Europeans were absorbed in trade and spying, political entreaties and treaties - and exploration. There is a growing literature. John Keay's masterly historic descriptive narrative of the encounters of Europeans with the area is called simply Where Men and Mountains Meet. Even in Ladakh, in that mysterious, implacable, beautiful and alien landscape, there were sites, sights and encounters in that political encounter of European interests on Asian soil, the so-called Great Game. And some of these military men, civil servants, bureaucrats, spies, explorers, must too have been draughtsmen.

We

came, as tourists, visitors, travellers. What we saw, filtered through

our own sensibility was, of course, an old medieval culture, so far

only lightly changed by the coming of technology, of the modern world.

These

watercolours are not snapshots but considered meditations and mediations

between the artist and the observer. Here, eloquently portrayed and

depicted in swathes of allusive colour, is something of the very nature

of Ladakh. Something that is beyond words, elusive, almost beyond

comprehension: the cross roads of High Asia, between two worlds. |