all text & images © Museum Associates/Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Ritual Objects

Fig. 4The ornate sacramental implements depicted in the paintings and displayed in the exhibition include priest’s bells, thunderbolts (vajra or dorje), flaying knives, ascetic’s staffs, and mirrors; water ewers and vases, butter lamps, skullcups, conch shells, and other vessels; and musical instruments, especially drums, horns, trumpets, and hand cymbals. Particularly noteworthy ritual objects in the exhibition are a skullcup made from a section of an actual cranium, signifying the transitory nature of existence; a set of three symbolic rock-crystal weapons, used in certain initiation rites; a water ewer for ritual cleansing; the paired thunderbolt and bell, representing the tantric union of compassion and wisdom, respectively; and a censer, used for burning incense as one of the peaceful offerings to the five senses. When not in ceremonial use, ritual objects are often displayed on elaborate altars along with other offerings and images of the Buddha and important deities.

Offering Cabinets and Offering Cakes

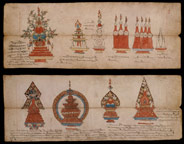

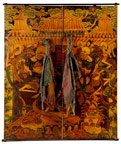

Offering cabinets (torgam), used to protect and store consecrated offering cakes (torma), are used in elaborate daily and annual rituals intended to gain the favor of the Buddhist protective deities (dharmapala). They are typically kept in the holiest area of a Tibetan monastery, the Protectors’ Chapel (gonkang) where images of the monastery’s tutelary deities reside, but can also be found in subsidiary shrines throughout a temple complex. Offering cabinets are sanctified with auspicious symbols and motifs emblematic of the particular protective deity being invoked. On monastic and temple offering cabinets, esoteric imagery predominates: faces of fierce deities (usually interpreted as generic dharmapala or various forms of Mahakala) and tantric motifs, such as skullcups filled with the organs and body fluids of slain enemies. Offering cabinets used by the laity in household shrines feature a limited repertoire of typically peaceful imagery.

Offering cakes (torma) made predominantly of yak butter and roasted barley flour dough are an important but ephemeral type of Tibetan ceremonial offering. Usually replaced annually, offering cakes vary in composition, shape, color, size, cost, and inherent symbolism appropriate to the deity beseeched and the rite performed. Torma offered to wrathful protective deities, such as those represented in the manuscript folios in the exhibition, are often festooned with billowing smoke and flames.

Textiles

Luxury textiles from China, India, the Middle East, and even Europe were widely imported into Tibet as tribute offerings and sumptuous trade items. Chinese silks in particular were used extensively in Tibetan monastic life: as garments for dancers and the elite, ceremonial seats for high lamas, various temple hangings, and mounts for thangka paintings. Painted renditions of intricate textile designs are also found frequently on the exterior of trunks, suggesting that they stored fine textiles. The two exquisite examples and the accompanying rug in the exhibition are embellished with the most popular textile design, an intricate latticework pattern called kati rimo (brocade) in Tibetan, which can be traced back to the Mongol culture of the Yuan dynasty in China (1260–1368) and even earlier in the western Islamic world. The smaller trunk is additionally embellished upon the top and sides with a cloud pattern derived from damask textiles of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).