| |

|

Introduction

Over the centuries, India has been composed of separate, competing kingdoms representing disparate cultures and reiigions. This exhibition enables a greater understanding of the rich variety of cultural traditions and complex political dimensions underlying India today. The word maharaja evokes for many a vision of splendor and magnificence. The image of a turbaned and bejeweled ruler with absolute authority and immense wealth is evocative, but it fails to do justice to his role in the cultural and political history of India. This exhibition re-examines the world of the maharajas and their extraordinarily rich culture.

Maharaja brings viewers precious art objects spanning three centuries that saw the decline of India's Mughal Empire in the early eighteenth century, the rise of new independent kingdoms, domination by the English East India Company, British colonization in 1858, India's independence movement and the collapse of British rule in 1947.

Qamar Adamjee, the Asian Art Museum's organizing curator for San Francisco's presentation of Maharaja, explains that the exhibition follows two principal narrative arcs: the first explores the secular and religious responsibilities of India's kings. The second traces the changing worlds of maharajas as their status transformed from independent rulers to "native princes" under British colonial rule.

Indian concepts of kingship, derived from ancient texts, evolved over time in response to political, religious, and social changes. By the 18th century, a shared expression of kingship had emerged across India, regardless of whether rulers were Hindu, Muslim or Sikh. Though rarely used formally until the 19th century, the title maharaja was adopted by rulers of kingdoms large and small across the Indian continent; after India became a British colony in 1858, it came to be used as a generic term to describe all of India's kings.

| |

|

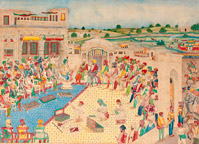

The Maharaja journey begins in the museum's Lee Gallery, which introduces viewers to the concept of royal duty (rajadharma) in Indian kingship. From military strength to administrative and diplomatic skills, maharajas were expected to adhere to a strict set of behaviors that were governed by specific protocol and etiquette, as at the durbar, or royal assembly, where state business was conducted. Ideal rulers were also pious individuals whose royal status was divinely sanctioned. In this capacity, maharajas participated in elaborate religious ceremonies to ensure the wellbeing of dynasty, state, and subjects. Royal duty also included the patronage of artists, musicians, poets, and craftsmen, and support of reiigious foundations.

|

|

Maharaja takes viewers into a throne room, the focal point of royal authority, in its ceremonial splendor. Visitors encounter ceremonial regalia, turban ornaments, swords, and other symbols of Indian royalty. Rare paintings in watercolors and gold give detailed representations of royal rule and present vivid portraits of individual rulers. An early 18th-century painting of Amar Singh II of Mewar portrays the ruler as an ideal king-haloed, bejeweled, and displaying the symbols of kingship.

| |

|

The Hambrecht Gallery opens to the world of Indian royal spectacle, where the maharaja reigns as a public symbol of authority. Paintings and other objects offer glimpses of grand pubIic celebrations and religious festivities, such as the 19th- century painting of the procession of Ram Singh II of Kota, with the lavishly dressed and jeweled ruler riding atop a richly adorned elephant. A ruler's primary duty was to maintain security in the kingdom, and weapons symbolizing his role as an able leader and warrior figured prominently in public ceremonies and visual representations. The visitor experiences the military aspect of royal duty through the paintings, armor and weaponry on display. An examination of palace life, royal entertainment and leisure activities includes musical instruments and board games, as well as splendid jewelry and exquisite costumes worn by royalty.

The Osher Gallery delves into the history and shifting power of kingships, dynasties, and empires over three centuries. With the decline of the powerful Mughal Empire at the dawn of the 18th century, a new political order took hold. The new order saw the resurgence of older Rajput kingdoms in central and western India alongside the emergence of new powers such as the Marathas and Sikhs. Intensifying the struggle for supremacy was the English East India Company, which by the mid-1700s had transformed into a major military and political force vying for a controlling stake in India.

The British East India Company, a trading organization founded in 1600, was attracted to India for the lucrative trade in spices, textiles, and other resources. Over the years, its powers extended beyond mercantile activities into political control. By the 1840s, many Indian regional rulers fell under British control; however, the regional powers featured in this section of the exhibition maintained their independent authority and a vibrant court culture for generations. Many of the objects showcased in the Osher Gallery can be associated directly with important Indian rulers of the time. The Kingdom of Mysore in southwestern India, one of the most formidable opponents of the British in India, was defeated in battle by the East India Company in 1799 and reconstituted under British control. The once-stable Sikh kingdom in the northern Punjab region fell to the East India Company in 1849. By the mid-19th century, the majority of former Mughal territories had been annexed by the East India Company; only Hyderabad, in the Deccan region, retained any form of independence. Over time, Indians resisted the increasingly powerful and oppressive Company through regional uprisings, and in 1857, a full-scale rebellion broke out, with various Indian royal families playing prominent parts on both sides. The conflict ended in 1858 when the British government, with the help of powerful Indian allies, gained command, bringing an end to both the Mughal dynasty and the East India Company. In 1877, Queen Victoria of England was declared Queen Empress of India. British rule in India was known as the Raj ("rule"), and as the largest, wealthiest, and most productive colony of Britain's empire, India became known as "the jewel in the crown."

Under British rule, the maharajas retained their kingdoms, but their status changed from independent rulers to princes of the British Empire. Maharajas continued to maintain order within their states, tax their subjects, allocate revenue, and patronize cultural activities, yet were subject to colonial rule. Thus, they performed the rites and rituals of kingship in a manner that fused traditional royal duty with Western models of governance.

|

|

Many maharajas were educated in Europe or by English tutors in India. Some adopted elements of Western dress and culture, such as cricket, fox hunting, and automobile racing. Travel to the West greatly expanded Indian princely patronage, and the new royal patrons had a profound effect on the production of luxury goods in Europe, as manufacturers responded to the tastes of their new clients. These exchanges led designers such as Cartier to introduce Indian-inspired designs to their European clientele. Outstanding among the royal jewels on display is the Patiala necklace designed by Cartier, which originally contained 2,930 diamonds, including the yellow 234.69-carat DeBeers diamond.

With the 20th century came widespread discontent with British rule, followed by the visionary leadership of Mahatma Gandhi. As a sustained movement for self-rule gained foothold, Indian rulers were increasingly marginalized in the shifting political environment. In response to these forces, the maharajas formed the Chamber of Princes in 1921 to represent a unified front for the interests of the Indian states. When India won independence from British rule in 1947, most princes signed the Instrument of Accession, by which their territories were integrated into the new nation-states of India and Pakistan. Yet even today, many maharajas remain potent symbols of regional identity and continue to exercise their royal duty, acting as guardians of the remarkable culture of India's royal courts.

| |

|

The exhibition also exposes the contribution of some legendary Indian princesses, who are shown to be cultured, educated, and sometimes fierce warriors. Among the Maharanis represented in the exhibition is Chand Bibi of Bijapur, the 16th century queen whose courage in battle made her a legendary figure in popular imagination. In the 20th century, Maharani Chimnabai, wife of the enlightened Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad Ill of Baroda, spent her life fighting for education and rights for women. Others such as Molly of Pudokkattai, Indira Devi of Coach Behar, Sita Devi of Kapurthala and Sanyogita of Indore-a renowned beauty photographed by Man Ray - were leading fashionable figures of their day.

Back to Maharaja main exhibition

|

|