(click on the small image for full screen image with caption.)

PERSISTENCE

OF A GENETIC SCAR by Julie Rauer

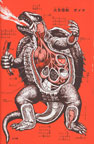

Twenty-two years after the mass obliteration of souls, the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and three days later on Nagasaki on August 9, 1945, monstrous deformities persisted in the Japanese psyche—tragically splintered by defeat, subjugation, humiliation, and inconceivable horrors—unable to command a return to a unified monolithic persona, the ordered cerebral imperative and societal dignity of pre-nuclear innocence. Nearly every middle aged Japanese man today, the post-war children of the 1960s, peered into the disfigured bodies of monsters in editor Shoji Otomo’s book, An Anatomical Guide to Monsters (1967), clinically visceral gallery of the explicably grotesque, creatures culled from popular television and movies dissected and rationally explained through the disturbingly familiar prism of darkest ersatz science. Abomination of nature crafted by human failings, the anatomical diagram of “Flaming Monster Gamera” (1967), is a chilling rendition of unnatural physiology in the service of impotent fury and thrashing confusion, the “subhuman” legacy of World War II. Brutal contortion of human flesh delineates both anonymous victims and dehumanized, mutilated survivors of the atomic bomb in Yosuke Yamahata’s wrenching book, Nagasaki Journey, unequivocally the most horrific photographic images of war’s aftermath ever taken. Writer Jun Higashi, member of Yamahata’s small investigation team dispatched to Nagasaki, witnessed an onslaught of temporal madness and monstrous deformity: “We saw a person running blindly in what he must have believed was a safe direction, but he was running on feet of bone—shock and fear prevented him from realizing that the flesh of his heels was gone. When a rescue team pointed out his grave injury, the man immediately lost consciousness and collapsed. We couldn’t bear to watch this event straight on—it was like something in a nightmare.” 1 Society cannot recover from such an epic scale of devastation, but may, instead, manifest trauma as a perpetual genetic scar—ontological chasm which moves as a consumptive demon ripping up through the generations as a peripatetic wound, egregious disfigurement banished from conscious thought, inflating to cartoon benignity in a pantomime of humanity, sutured gash badly sewn and always reopening, futile replacement of scarred mortality for the immaculate technology of machines, and finally as the wholesale abandonment of frail humanity for alternative existential states. Successive strata of the crippled human condition pervade Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture, the evocative and remarkably eloquent museum exhibition, elegiac publication (essays and images set in a bilingual catalogue co-published by Japan Society and Yale University Press), and series of arresting public art events organized by Japan Society in collaboration with Public Art Fund in New York City, an unprecedented conjoining of media in service to the spiritual abyss that defines a nation’s subculture. Curated by artist Takashi Murakami, the museum’s gallery artworks and their public appendag.es, on view from April 8-July 24, 2005, writhe through subway stations and constrict building facades, with the anguish, ferocity, melancholic rumination, inexorable repulsion, and fragile optimism of their creators—artists profoundly influenced by otaku culture, or those with a monumental, all consuming interest, inferring pointedly derogatory overtones in Japanese culture. Comparable to the American “nerd” or “fanboy”, otaku—literally translated as “house” from Japanese—denotes staunch individualism outside the Japanese mainstream in those personalities relegated to the debased fringes of society, further extending to fanaticism approaching cultism in its strident video collectors and technophiles divested of personal lives beyond their dominant reigning obsession. “Although some otaku prize themselves as “genetic” otaku, all are ultimately defined by their relentless references to a humiliated self.” 2 In the coalescence of various psychological states of the post-war Japanese psyche, the defining parameters of universal human suffering can be found: “subhuman”, signifying hideous deformity and repulsion by civilized society, the monstrous underbelly in exiled fury; the unformed and incomplete “protohuman”; “flawed human” in perpetual repair or denial of the present human condition, appropriating history as panacea; the genetic or cyborgian amalgam of man and machine, “hyperhuman”, enhancements which ironically elevate and siphon life in a Faustian bargain with technology; and finally “superhuman”, offering cathartic transcendence of mortal existence, encapsulation of the soul outside of its given body, fluid and transmutable, virtual immortality.

Contemplated and analyzed through the sphere of Judeo-Christian iconography (a strong thematic component of masterful Japanese anime such as Neon Genesis Evangelion [1995-96; twenty-six episode television series], its obscure lexicon including the ruinous weapon, “Spear of Longinus”, the spear used to pierce the crucified Jesus), the Japanese states of being ( evident in numerous Little Boy works) run curiously, fascinatingly parallel to the various historical manifestations of the Golem, the Jewish folklore figure revealed in successive literary references to be monstrous, embryonic, flawed servant of humankind, robotic automaton, and inanimate vessel endowed with fleeting life. In a frightening, mid sixteenth century perversion of the natural order, when men are blithely capable of creating unthinkable “subhuman” instruments of destruction, Elijah of Chelm made a golem with a “Shem” (any one of the names of God), written on a slip of paper and inserted into either the mouth or forehead of the golem to bring it to life, nearly triggering apocalypse: “It is said to have grown to be a monster (resembling that of Frankenstein), which the rabbi feared might destroy the world. Finally he extracted the Shem from the forehead of his golem, which returned to dust.” 3

Godzilla, presented in Japan Society’s gallery as thirteen small PVC figurines (spanning 1954-1995) and one large FRP work the size of a living Komodo dragon (1989), all sculpted by Yuji Sakai, is the symbol of rage against its creators, Japan’s own Golem and deliverer of inevitable annihilation. Resurrected from deep sea dormancy and transformed from benign reptile to marauding destroyer of Tokyo by a hydrogen bomb, Godzilla is both the wrath of an innocent altered by unseen catastrophe to “subhuman” fate, and the embodiment of relentless incendiary deluge by unstoppable forces, the 1945 fire bombings which reduced Tokyo to ashes and the A-bomb which obliterated Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Metastasis and mutation appear to have sculpted Fresh Gasoline (1988-89)—completed one year earlier, but separated Siamese twin to Aesthetic Pollution (1990)—hulking manifestation of toxicity perched above the interior bamboo garden and drained waterfall in Japan Society’s galleries. Its very pigmentation is jaundiced, sickly, radioactive, hues beyond illness, shades of inextricable collective decline. Amalgam of arthropodal, entomological, human, and botanical, Noboru Tsubaki’s infernal creation was forcibly merged by catastrophic circumstance, yet whatever its demonic intentions, its existence is one of wrenching pathos, of life gone grotesquely astray from normal biology.

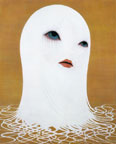

Shorn of senses and humanity, Hideaki Kawashima’s acrylic paintings conjure faces that defy their anachronistic trappings of traditional portraiture, “protohuman” sacks without nostrils or ears, denied breath and music and hence the capacity for sentience or civilization. Soak (2004) presents fetal malformation devoid of innocence, a visage of ghastly eyes crackling with the duality of earthy human venom and alien detachment—with no delineation of individuality—stripped of tongues and teeth, veins, necks and warm bodies. Gelatinous and malformed, Kawashima’s abominations exists as both the result and progenitors of past, present, and future cruelty. Destiny and possibility await the unformed, which promises in uncertain blueprints the heights of nobility in tandem with egregious frailty and consequent, often dire, transgression. Judeo-Christian literature describes the Golem in its “protohuman” state: “This word occurs only once in the Bible, in Ps. Cxxxix. 16, where it means ‘embryo’. In tradition everything that is in a state of incompletion, everything that is not fully formed, as a needle without the eye, is designated as ‘golem’ (‘Aruch Completum’, ed. Kohut, ii. 297). According to Jewish scholarship, “God created Adam as a Golem”; extending the concept to the religion’s creation ideologies, the Gnostics, following Irenaeus, “also taught that Adam was immensely long and broad, and crawled over the earth”, an assertion which may be viewed as the blueprint for humanity 4. Doomed to repeat its mistakes ad infinitum, the “flawed human” state exists in an almost constant cycle of denial and inadequate technological repair, unable to progress and flourish. World War II left indelible stains on the Japanese psyche, brutally fractured and, at times, inconsolable regarding the cultural, aesthetic, and scientific intrusions of the West in the post war reconstructive years. In his luminous, melancholic essay on aesthetics, In Praise of Shadows, esteemed Japanese novelist Jun’ichiro Tanizaki ruminates eloquently on the depths of societal tragedy: “…there can be no harm in considering how unlucky we have been, what losses we have suffered, in comparison with the Westerner. The Westerner has been able to move forward in ordered steps, while we have met superior civilization and have had to surrender to it, and we have had to leave a road we have followed for thousands of years. The missteps and inconveniences this has caused have, I think, been many.” 5

High tech innovations, gadgets, and tools arrived in Japan in 1970 with an explosion of Western style conveniences and home appliances, feeble panacea for the gaping existential wounds of only twenty-five years earlier. Technology over human ingenuity, endeavor, and individual initiative—science alleviating and finally supplanting the “flawed human” state—was sublimely embodied by Doraemon, a time traveling, robotic cat/babysitter/ angel from the twenty-second century assigned to help trouble magnet Nobita Nobi, a Japanese schoolboy plagued by underachievement and consequent crises. In episode one, “All the Way from the Future” (which can be viewed in Japan Society’s gallery), of this wildly popular TV anime series, first shown in January 1970, Doraemon springs from the womb of the boy’s shallow desk drawer, declaring: “I am here to save you from an awful fate.” Delivering on his promise of instant solutions and omnipresent guidance—supplying the deeply flawed Nobita with an endless parade of secret twenty-second century tools extracted from a “Four-Dimensional Pocket” in his stomach—the enchantingly hilarious cat from a far better future corrects human folly and mends trauma, even staving off future financial ruin and the loss of face. Exposing the “flawed human” in Jewish folklore, underscoring decided parallels to the conceptual underpinnings of Doraemon, the Golem appears in yet another form as servant to an imperfect rabbi: “The best-known golem was that of Judah Löw b. Bezaleel, or the ‘hohe Rabbi Löw’, of Prague (end of 16th cent.), who used his golem as a servant on week-days, and extracted the Shem from the golem’s mouth every Friday afternoon, so as to let it rest on Sabbath. Once the rabbi forgot to extract the Shem, and feared that the golem would desecrate the Sabbath. He pursued the golem and caught it in front of the synagogue, just before the Sabbath began, and hurriedly exracted the Shem, whereupon the golem fell in pieces.” 6

Outliving its creator, Fujiko F. Fujio, who died in 1996, Doraemon has returned to repair dysfunctional human lives, in feature films released annually since 1980. A seven foot long case dominates an entire gallery wall, glass coffin of populist sentiment filled with Doraemon merchandise, including a First Aid Kit engineered for maximum adorability, and wrist watches that soothe: “Don’t cry anymore” and “stay together forever” on their bands—assurances of permanence, love, support, and healing for a deeply scarred country. Extolling the “hyperhuman” state of mind and its often wrenching, poetically charged expression in Japanese anime, the brilliantly realized, exquisitely drawn television series (later, a single feature film), “Cowboy Bebop”, a rather glaring and curious omission from the Little Boy exhibition, melds grand operatic themes of human tragedy—betrayal, sacrifice, unrequited love, the nature of civilization in a future of epic unraveling, technologically altered consciousness, wrongful death, and the legacy of persecution—with sardonic, pathos laden wit in a densely composed web of musical scores incorporating classical strings and brass, church organs, the distinctly American art forms of jazz and blues, and futuristic techno pop. Cyborgian amalgams of man and machine battling free will (comparable to the Golem’s robotic persona in Jewish mythology: “the golem grew in size and could carry any message or obey mechanically any order of its master” 7 ) abound in a splintered, jittery universe of tenuous loyalties, eco-terrorists, genetically engineered Corgis, anti-heroines with implanted memories, bounty hunters lovingly pruning bonsai with bionic arms, and children with enhanced hyper driven brains jacked seamlessly into supercomputers. Weaving the reciprocal viscera of mortal flesh and circuitry, the increasingly complex relationship of the animate and inorganic, with consummate artistry and a new measure of representational subtlety and ideological sophistication, two stunning recent Japanese films by animator and director Makoto Shinkai, Voices of a Distant Star and The Place Promised in Our Early Days (viewed by this writer in press preview at a private screening held by New York-Tokyo and ADV Films, major producer-distributor of Japanese animation, and not yet in general US release), speak of elastic time and intergalactic wars, ravenous technologically fuelled dreamscapes, fundamental promises made by one human being to another, and the smell of civilization in its final lurid moments before disintegration.

Pristine visions of the “hyperhuman” chapter of consciousness, characterized by dazzling, futuristic optimism, is best evinced by Shigeru Komatsuzaki’s meticulously rendered mixed media paintings, seventeen of which are on display at the Japan Society. From Space Colony B to Marine Food Recovery Ship, Rescue Tower, and Underground City (all 1982), idealized visions of an autonomous Japan abound, self-sufficient fortress equally dominating deepest sea and space—spotless empire untouched by war. Alternative existential states of portable consciousness, migratory life capable of extraction and multiple encapsulations in shells both organic and engineered, defines the “superhuman” state, which is epitomized in the anime lexicon by the serial Ghost In the Shell television series and two feature films, most recently Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence, which poses what may be one of the most pressing questions lurking in our collective technological future: When machines learn to feel, who decides what is human? Yet in medieval times, the subject of reanimating lifeless substances and reinvestment of the soul was shockingly present in the sphere of philosophical thought; “in the Middle Ages arose the belief in the possibility of infusing life into a clay or wooden figure of a human being, which figure was termed ‘golem’ by writers of the eighteenth century”. 8 Past and future are facing mirrors in the anime universe, with the mortal presence—wounded and scarred by the brutality of history and the inevitability of its repetition—caught perpetually in between, always forced to choose which way to turn next. “A warm wind

began to blow. Here and there in the distance I saw many small fires,

like elf-fires, smoldering. Nagasaki had been completely destroyed.”

|

FOOTNOTES: 1. Y. Yamahata, Nagasaki Journey: The Photographs of Yosuke Yamahata. August 10, 1945 (Pomegranate Artbooks, San Francisco, 1995), p. 72. 2. T. Murakami, “Earth in My Window”, translated into English by Linda Hoaglund, Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture, (Japan Society, New York, and Yale University Press, Connecticut, 2005), p.132. 3. I. Singer, Ph.D., The Jewish Encyclopedia, (Ktav Publishing House, Inc. New York, 1963), vol. 6, p.36. 4. I. Singer, Ph.D., The Jewish Encyclopedia, (Ktav Publishing House, Inc. New York, 1963), vol. 6, p.36. 5. J. Tanazaki, In Praise Of Shadows, translated by T.J. Harper and E.G. Seiden sticker, (Leete’s Island Books, Connecticut, 1977), p.8. 6. I. Singer, Ph.D., The Jewish Encyclopedia, (Ktav Publishing House, Inc. New York, 1963), vol. 6, p.37. 7. I. Singer, Ph.D., The Jewish Encyclopedia, (Ktav Publishing House, Inc. New York, 1963), vol. 6, p.37. 8. I. Singer, Ph.D., The Jewish Encyclopedia, (Ktav Publishing House, Inc. New York, 1963), vol. 6, p.37. 9. Y. Yamahata, Nagasaki Journey: The Photographs of Yosuke Yamahata. August 10, 1945 (Pomegranate Artbooks, San Francisco, 1995), p. 51. |

asianart.com | exhibitions