Asianart.com || INTRODUCTION || Exhibitions

Click on small images for full images with captions

|

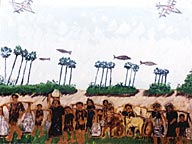

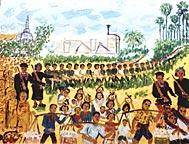

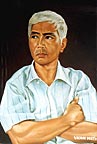

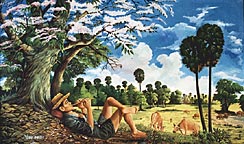

VANN NATH was born in Battambang Province in 1946. He is best known for the series of paintings which he made in 1980-81 based on his experiences as the prison painted at the infamous Khmer Rouge torture center, Tuol Sleng. "My picture wishes to show what life ideally can be like in the countryside. The cowherd lying under the tree is free in his heart. He is his own master and does not suffer from oppression or intimidation. He lives honestly by his own labor and in peace and harmony with his own surroundings. He has no fear of anything and is not afraid that anyone will steal his possessions or his animals. It is thus the opposite of my paintings of torture and sadness. While painting this painting I was happy and hopeful. The Tuol Sleng paintings I painted to document what had happened but their painting was difficult for me." PHY CHAN THAN studied traditional painting at the School of Fine Arts in Phnom Penh in the early 1980s. He then studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest, Hungary, from which he received his M.F.A. in 1992. Phy Chan Than is currently a lecturer of painting at the Faculty of Plastic Arts of the Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. The name for the Kabok tree (Ceiba pentandra) in Khmer is "Koh", a word which also means mute. During the Pol Pot era, an oft repeated saying had it that "if you want to live, grow a Koh tree in front of your house." Part official threat, part unofficial advice, this saying was directed at the "new people" or "17th of April people" (i.e., those who fled from the cities to the countryside in April 1975). The saying invited the addressed to remain silent about everything that they had seen, heard, knew, or felt. As Phy Chan Than explains it: "At the center of

my canvas, I have painted the trunk of a Koh tree which stands for all

the people who lived under the regime of Pol Pot. The areas on each

side of the trunk represent the savagery and threats of that time. Two

circular forms on the upper right and the middle left represent how

Cambodia was as separate as another planet from the rest of the world

then. Although we had been members of the international community, during

the Pol Pot regime no country came forward to help us in any way."

The colors on either side of the Koh tree attempt to represent the two

different tactics used by Angkar (the leaders of the Pol Pot regime).

The red side represents the "use of terrible acts when someone

did something wrong or when they forced us to work." The green

side, on the other hand, represents, the hopeful, encouraging words

which "Angkar used during meetings or when they coaxed us to do

something." A red river runs across the middle of the canvas and

flows over the trunk of the Koh tree recalling the later slogan used

in the early 1980s to describe the Pol Pot era as a time when "the

tears and the blood of the Khmer ran like a river, and their bones made

mountains." At the bottom, gouging into the trunk of the Koh tree,

is "a hole which Angkar dug in order to try to uproot the Koh tree

which stands for the people of the 17th of April." "They were

constantly trying to kill or uproot us," Phy Chan Than explains,

"we had no value to them." The trunk of the Koh tree itself

is fractured in several places "to show the scars which all the

survivors still bear today both inside their bodies and in their hearts."

|

|

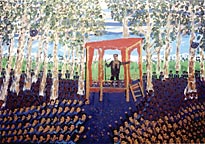

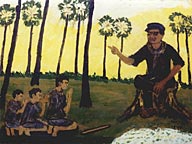

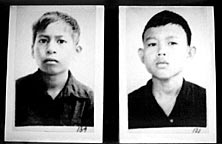

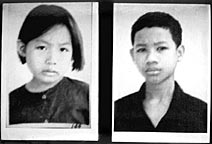

LY DARAVUTH was born in Kampong Thom Province. In 1980, he went to the refugee camps in Thailand, and he emigrated to France in 1983. He studied art history and visual arts at La Sorbonne (Paris, France). He returned to Cambodia in 1993 and is currently a lecturer of art history at the Faculty of Archeology of the Royal University of Fine Arts. He is the co-founder of Reyum. During Pol Pot time, certain teenagers and children delivered messages for Angkar all over the country. The photographs used in this installation were collected by the Documentation Center of Cambodia and are said to show such Khmer Rouge messengers. "After talking to Youk Chhang, the director of DC-Cam, I became interested in the strange idea of the truth and its documentation. Because of the blurred black-and-white format and the numbering of each child, we tend to read these photographs first as images of victims, when they are ‘really’ messengers and thus people who actively served the Pol Pot regime. The fact that upon seeing their faces, I immediately thought of victims, made me uneasy. My installation wishes to question what is a document? What is ‘the truth’? And what is the relationship between the two?" Through various visual means , the photographs have been physically deteriorated and set amongst similarly doctored images of children from the present. The installation thus set a curious scene in which confusion and ambivalence reign. If at first glance we assume by their poignant poses and format that the pictured children are victims, "Messengers" leads us to admit that perhaps it is impossible to access any truth other than that once a child stood before a camera and was photographed. Who they are, what they did, and when they lived, is not revealed by the photograph which we still hold somehow to be the direct record of the truth. If upon entering we are seduced into easy sadness, we leave uneasy, recognizing the difficulties of ever discerning "the truth" retrospectively. NGETH SIM studied at the Faculty of Plastic Arts of the Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh in the late 1960s. He taught painting at the Faculty for three years before the beginning of the Pol Pot era. In 1980, Ngeth Sim went to the Thai border and entered the camps, where he remained until 1983. Sent to France as a refugee, Ngeth Sim has lived and painted in Paris ever since. "My poor father, at the moment when the Khmer Rouge led you away, I fixed on your face intently. At the bottom of my heart, a thousand thoughts clashed and overwhelmed me. I couldn’t speak. I remained mute in front of them and only the tears flowed down my cheeks. I sensed that I was going to lose you and life left me at the same time that they were taking yours. I did not have the force to protest in front of these torturers, to prevent them from taking you and killing you. Today still, this memory beats against my chest and keeps me from complete happiness. When I think of it, the feeling overwhelms me that I did nothing to return the love that you had given to me. I am truly an ungrateful son. Dearly beloved father, I pray every night that your soul will pardon me." SOEUNG VANNARA studied at the School of Fine Arts in Phnom Penh during the early 1980s. He was later sent to Poland to study at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, from which he received his M.F.A. In"monumental painting" (fresco and wall painting) in 1993. He is currently a lecturer in painting at the Faculty of Plastic Arts of the Royal University of Fine Arts. "There is a common belief that people are formed by combining the four basic elements of water, earth, wind, and fire. As long as these elements remain joined together, people live. These elements, however, are only borrowed, and they are slowly given back over a life time. With the smoke and ash of their death, people return to the separate elements that they originally were. Only their spirit floats up, often eventually entering into another person, newly born. When people die because of terrible deeds and torture, what happens to their spirits? Do these spirits rest peacefully? Can they enter a new born or not? My painting reflects on these questions. The central sweep of reds and yellows recalls the basic elements of fire and smoke while the contrasting blue and green areas invoke water, ash, wind, and clouds. The forms in these areas are wave like, echoing natural elements but also taking the shape of Kbach (Khmer ornaments). Half of the central face of the praying figures dissolves, burning and flowing, continuing on into another form. Other half faces, features, and remains of objects are woven into the shapes and colors. I try to express spirits and what they leave behind." For more information email Reyum Gallery : An Introduction by Sarah Stephens [top] |

||||||

All images and captions copyright © 2000 Reyum. All rights reserved.