A portion of the following is excerpted from the exhibition catalogue introduction authored by Dr. Pratapaditya Pal.

click on images to view larger image with caption

A major exhibition of Tibetan art has been organized by The Albuquerque Museum in association with Asian scholar, art historian and Getty Fellow Pratapaditya Pal. The exhibition will open in Albuquerque October 18, 1997 and run through May 24, 1998.

|

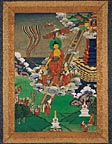

| Buddha Sakyamuni Western Tibet, ca. 1000 |

Unlike Buddhists in other countries, Tibetans are remarkably eclectic and do not deny the validity of any school. Although they primarily follow the Vajrayana (also known as Mantrayana and Tantrayana) form of Buddhism, their acceptance of the early form of the religion is implicit in the strictly celibate monastic system imposed by the great reformist monk-teacher Tsongkhapa (1357-1419) and the importance given to the group of sixteen arhats and to moralistic stories of previous births of the Buddha known as jataka and avadana.

|

| Portrait of Wangchuk Dorje, the 9th Karmapa Artist: Karma Rinchen Eastern Tibet (Kham), 1598 |

|

|

|

| Descent of the Buddha Eastern Tibet (Kham), 19th century |

A Flying Mahasiddha Eastern Tibet (Kham), 18th century |

Female Devotee Southern Tibet, 15th century |

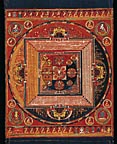

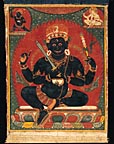

Among the many traditions of Buddhist art the three areas where the Tibetans have made the most significant contributions are mandalas, images of angry deities, and portraiture.

|

| Mandala of Sarvavid Vairochana South Central Tibet, early 14th century |

Although the mandala has many layers of meanings, primarily it is a symbolic mansion or citadel for the gods. It is a temporary home, to where the deity descends when invoked by the adept of the officiant. It is a strictly symmetrical, geometrical form consisting chiefly of circles and squares, and uses the four primary colors: white, yellow, green, and red. And yet, every mandala is different formally, as can be seen even from the few examples selected for this exhibition.

|

| Mahakala, the Protector of the Faith South Central Tibet, 13th century |

On yet another level the wrathful deities are the destroyers of the terrors that lurk in the human mind, the defilements and poisons. Thus, they not only provide protection from external dangers, but also from internal demons.

|

|

|

| Transcendental Buddha Mahavairochana Central Tibet, 12th century |

Transcendental Buddha Amitayus Central Tibet, 14th century |

Bodhisattva Manjusri Central Tibet, ca. 1300 |

|

|

|

| A Serpent Deity Central Tibet (Densatil Monastery), 14th century |

A Reliquary in the Form of a Stupa Central Tibet, 13th century |

Charm Box Tibet, 19th–20th century |

It will not be possible to discuss the fascinating subject of portraiture at length here but the selection of a large group of "images" of historical figures in this exhibition should not only demonstrate the enormous variety of such representations but should also kindle interest in others. Even though the monks are not depicted with obvious signs of divinity, certainly their gestures, attributes, and nimbuses emphasize the fact that they are "emanations" of specific deities, or have attained "Buddhahood."

Along with the images and mandalas, a great variety of objects and implements are used in the complex rituals performed in Vajrayana Buddhism. The exhibition includes a selection of the most important of such implements.

A major publication will accompany the exhibition, illustrating each of the objects and including essays by Dr. Pal, Dr. Robert Thurman, Robert Sachs, Dr. Thubten Norbu, brother of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and Tashi Woser, who will relate the oral histories of Tibetans who have relocated to New Mexico.

|

| Flint Purse Tibet, 18th century |

This exhibition is presented admission-free by the City of Albuquerque, through The Albuquerque Museum, a Division of the Department of Cultural and Recreational Services. The Albuquerque Museum is located at 2000 Mountain Road NW near Old Town. Museum admission is free and tours may be arranged by calling (505) 243-7255. Museum hours are Tuesday through Sunday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.; closed Mondays and City holidays. The Albuquerque Museum is accessible to persons with disabilities. If you require special forms of assistance to enjoy Museum activities or to obtain this information in an alternative format, please contact the office at least five business days in advance at (505) 243-7255 (voice) or (505) 764-6556 (TTY).