Darkness and light

In

Asia the gods dwell in darkness, in the smoky, innermost shrine of the

temple, surrounded in stillness by a few butter or oil lamps. Only

rarely do they leave this abode: then, however, the gods are bathed with

water and light and are carried around through their cities in festive

processions. Until again they return to the darkness of their

sanctuaries.

Shall

we treat these sculptures of bronze as deities which after all they

still are, or as art objects and exhibits? Shall one leave them in the

darkness of a deep alcove, with traces of blood sacrifice and vermilion

on them, the golden patina only sparsely lit, or shall one expose them

to bright daylight and its equivalent of cold Halogen or Neon

illumination? Profane them, once and forever, to become objects in the

history of religions or otherwise treasures of art?

Can we, to

paraphrase Joseph Beuys, forego their charm which goes beyond beauty?

Would not a humane museum concept almost demand that the gods of an

ancient culture be left, as far as possible, in

their context and not be divested of darkness, their most common shroud

?

Götz

Hagmüller: "Wenn das Licht ausgeht in Kathmandu" (When the

lights go off in Kathmandu), Wien 1991

Appropriate

Exhibition Technology at the Patan Museum

Above all with regard

to maintenance and equipment which are available locally – there was

no high-tech to start with. Other future repairs, the technical

equipment used had to be compatible with the skills, materials and

constraints also necessitated some compromises after a careful

consideration of the pros and cons involved. In the absence of any

patent recipes in such a situation, the endeavour to adapt to local

conditions and available skills was a particular challenge. Above all with regard

to maintenance and equipment which are available locally – there was

no high-tech to start with. Other future repairs, the technical

equipment used had to be compatible with the skills, materials and

constraints also necessitated some compromises after a careful

consideration of the pros and cons involved. In the absence of any

patent recipes in such a situation, the endeavour to adapt to local

conditions and available skills was a particular challenge.

For the museum’s

abundant information display, the graphic design and production of more

than 200 object labels and some two dozen gallery texts could make good

use of the rapidly developing computer and print technology in Nepal.

The humid climate, and

the high amount of dust and pollution in the air of the Kathmandu Valley

are fundamental problems for a museum, particularly in a historical

building which does not allow comprehensive glazing of its windows, and

precludes an air-conditioning system. The necessary protection of

exhibits has therefore been almost completely confined to the showcases

– apart from a number of large, free-standing objects. The showcases

are made of simple steel sections, welded and screwed together, with the

glazing and sealing made as airtight as possible. The objects are

protected against the heat from the light compartment above by sandwich

panels of glass. Showcase doors have been avoided in all those showcases

which are not built into walls, in order to avoid problems of

locking and air-tightness, which makes their contents only accessible by

removing the entire glazed box frame from the case bottom. This solution

involves a concession to the fact that the frequent high humidity is

reduced only during admission hours, and then only slightly (by heat

radiation from the light compartment) and cannot be regulated by

humidity equalizers (e.g. silica gel), which would require frequent

access, as well as an unrealistic high level of competence and control.

However, the light compartments can be easily opened for inspection and

maintenance and are also well-ventilated, in order not to reduce the

lifespan of their lamps through excessive heat.

The tempting array of

modern light fixtures on the international market has also been

dispensed with, in particular low-voltage technology: not only for

reasons of maintenance and supply, but also because project

experimentation has proved that the normal incandescent light of the

reflector bulb (which is available in Nepal) provides the best

illumination for sculptures anyway, especially for those made of bronze

or gilt copper. This light is neither as sharp as that of

12-volt-halogen bulbs, nor as diffuse and unreflective as that of

fluorescent tube lights.

In some cases, mirrors

are inserted into the bottom of the showcase to reflect the light from

above and thus provide additional contour lighting for the exhibits from

below – a minor reference to the original method of lighting, which

placed oil lamps on the floors of the shrines.

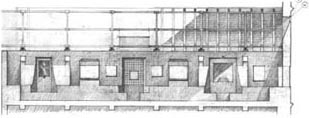

Gallery

G : Deep bay windows on the second floor provide sitting

comfort and views of the square below. The original mud floors

have been replaced by handmade

terracotta tiles. |

Gallery entrance, first floor: The carved wooden door was salvaged from the

demolition of an old house. The triangular loopholes are for the

passage of spirits who avoid thresholds in their flight path. |

Gallery

G: The photograph was taken before the Museum’s section on

traditional metal technology was fully installed. The bay

windows on the left provide a view of the Northern part of Patan

Darbar Square.

|

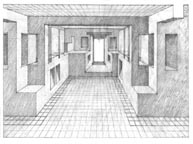

Gallery

D: Looking through into Gallery E. Stone sculptures of the

Vedic Gods Chandra and Surya on the left, and of tantric deities

of Nepal in the hanging show cases. |

West-wing

gallery on top floor: The gallery overlooks Darbar Square. It is used for

meetings and lectures, and for banquets on special occasions. |

View

from the South tower pavilion over Darbar Square: The bell was rung during rituals invoking the gods in

times of severe drought. Krishna Mandir in the right background. |

|

|

|

|

Top Right: Perspective drawing

of early design by Roland Hagmuller

Top Left: The southern part of

gallery E, with a triangular alcove protruding through gable wall |

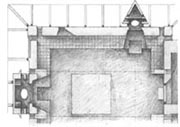

East wing, First

Floor, Gallery E

A triangular hole under the ridge of the gable wall allows a ray of sun

light to enter during noon hours, apart from providing the traditional

exit for volatile spirits.

The

crossing of two invisible lines (defined by the axis of alcoves and

doors as dominant features) suggests the main route of visitor

circulation where it turns between the East- and the South-wing.

The Colour Scheme: monochrome

In 1887 Max Müller,

the German Sanskrit scholar and editor of The Sacred Books of the East,

noted that our ancestors of 2,000 years ago were more or less colour-blind

– as most animals are. Xenophon was aware of only three colours in the

rainbow (purple, red and yellow) and Democritus of only four (black,

white, red and yellow). Even Aristotle spoke of the three-coloured

rainbow and for Homer the sea evidently had the same colour as wine.

One could presumably

make a similar claim for rural Nepal, as also for many of the

traditional societies in the Third World: many differences, nuances and

blends of colour are not even perceived and therefore not designated by

words. Colour is a luxury. A few colours do indeed have their own

exactly defined symbolic values in painting and ritual, but they are

neither artistic nor individual means of expression as such. Most

people's clothing in non-urban Nepal tends to be 'earth-brown' – the

same colour as the architecture. The women also use red, especially at

festivals, and red is also the colour of the flag aprons on the eaves of

the pagoda roofs. In everyday life, however, the colours that

predominate are those of rust or dust, of earth and terracotta, of

untreated wood and natural yarn.

In only a few

historical buildings are there coloured interior rooms. An even rarer

sight are coloured wooden elements which are visible from outside, as in

the case of the Golden Window of the Patan Darbar 100 years ago, which

Gustave Le Bon documented in some detail and published in the form of a

coloured engraving. However, since the date of the paintwork is unknown

and its authentication as dating from the early 18th century is

doubtful, there has so far been no attempt to reconstruct what can in

any case hardly be ascertained from the scarce traces of paint which

remain.

Even if it might seem

as if the above assumption of colour-blindness in traditional Nepal is a

justification of the monochrome use of colour in the Patan Museum, the

choice of colours did in fact arise almost naturally. Building

components such as brick, terracotta and wood were already there, as

were a couple of whitewashed elements. Yet the inner walls were

deliberately not painted the traditional white but a brick colour – on

the one hand for perceptual reasons, to reduce the differences of

brightness in the surrounding areas (to the advantage of the illuminated

museum exhibits), on the other hand for the practical reason that the

underlying plaster, which consisted of brick dust and lime mortar, had

this colour anyway, so that the inevitable damage caused by the wear and

tear of the paint would then not be too conspicuous.

The choice of colour

for the frames of the showcases and for all new, visible construction

and furnishing elements which were made of steel had a similarly

practical background. The dark rust-brown colour is the same tone as the

usual rust-protection coat, which can be obtained in every paint shop in

Nepal and which would therefore not have to be specially mixed when used

for redecorating in the future (the satin surface was obtained by adding

boiled linseed oil).

Consequently, the

colours used for the insides of the showcases, as well as for the

information boards which present pictures and texts, were simply a

logical consequence of the foregoing: their matte brick-red, sepia or

sandy tones produce the most pleasant colour scheme for the majority of

the exhibits, the smooth and reflective surfaces of which are usually

made of bronze or copper and in many cases are also gilded.

To

bring the circle to a close, even the museum's textiles and the

traditional clothing of the gallery attendants have been included in

this monochrome scheme.

|

East wing, First Floor, Gallery A

This

gallery is the first one the visitor enters. It provides an introduction

to the exhibits and explains how to recognize the various Hindu and

Buddhist deities or ritual objects by their particular features.

One

showcase and two separate stone reliefs in this gallery display

miscellaneous aspects of iconography and include objects which cannot be

identified: e.g. the faceless image of the repoussé shrine in the center

would only be recognized by the family who had dedicated this object to

their personal deity in 1855. |

Design

for showcase no. 4

|

South wing, second

floor Gallery D

To maximize a sense of space in the long and narrow galleries,

freestanding exhibitions were kept to a minimum and showcases were

suspended from the ceilings.

Design of show case

interiors

Although most showcases

are standardized to some extent with regard to measurements and technical

details, each case has a different interior form, individually designed

for its particular group of exhibits.

Within its group, each

object again has been given a particular space, either in a niche receding

from the slanting main plane or on a pedestal protruding from it. Thus,

each exhibit has its own “spatial aura” in distinction from its

neighbors, and each group is gathered in a homogenous setting.

|

|

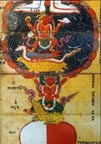

| Manuscript of Tantric Hinduism

(detail); Bhaktapur, Nepal, 17th-18th century, handmade paper, ink,

watercolors, Object 772 |

In some cases, mirrors

are inserted into the bottom of the showcase to reflect the light from

above and thus provide additional contour lighting for the exhibits from

below – a minor reference to the original method of lighting, which

placed oil lamps on the floors of the shrines.

The design for this

individual showcase takes into account the unusual dimensions of the

exhibit: a continuous illustration spreading over 21 folios of a leparello-type

manuscript measuring 20 cm in width and two meters in length.

It would have been

logical to display the manuscript vertically in order to keep upright both

the script and the image (a schematic human figure with all chakras

depicted above each other along the spine), but that would have meant

forgoing the possibility of seeing and reading each folio easily and at

close range.

Thus the manuscript is

laid out horizontally, as it would have been on the floor or a table. The

60 degree angle of the glass sides of the case and the two horizontal

hand-bars invite one to lean a bit over the exhibit for a closer view.

Wall niches

Traditional wall niches of the Malla period were replicated with

precast concrete elements set in the mud-mortar masonry walls and housing

concealed lighting.

Although this particular

shape of niche shows late influence from Mughal India, its archetype is

also found in the earliest flowering of Nepalese art, the Licchavi period

(4th-7th c.).

North wing, second

floor Gallery G, technology section

The niche above one of the typical

latticed windows was converted into a showcase with a glazed steel frame

in front and a hidden light box above. The case exhibits a pair of gilded

bronze hands, cast in the lost wax (cire perdue) process which is

explained in this gallery.

Bigger than life-size,

the hands may have been part of a large image of Shakyamuni, the

historical Buddha (a superb example of which is shown on the facing page). In this most common pose he is seated in meditation, one hand in

his lap, the other in the gesture of “calling the Earth to witness” by

touching her with the tip of the middle finger at the moment of his

enlightenment. |