click here for Tibetan version of the article | Download the PDF version of this article

A Study of mKhyen brtse chen mo dge bsnyen rnam rgyal, his mural paintings at Gong dkar chos sde and the mKhyen lugs school of Tibetan painting *Translator's note: This article is a revised version of Penba Wangdu's research on Mkhyen brtse, first published in Tibetan language, without illustrations, in Journal of Tibet University, 2010, 4:112-117. Although readers may be familiar with the term mKhyen bris, which refers to mKhyen brtse's painting style, throughout this article Penba Wangdu uses the term mKhyen lugs, the mKhyen brtse aesthetic, which refers to his style in both painting and sculpture, as he was a master of both media.”

by Penba Wangdu

Summary translation by Amy Heller

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions)

Here in the land of snows, for a long time there was relatively little knowledge about the history of painting traditions but this is now starting to change. The most remarkable paintings now extant by great artists of the past include the works of the mid-15th century in Central Tibet, in particular the paintings of the style known as mKhyen lugs, the school of mKhyen brtse, which developed precisely in this period. There are three principal sources of extant paintings: first, the Gongkar monastery where the master artist mKhyen brtse dbang po worked personally, secondly the paintings which remain by the students of his ateliers, and thirdly, those paintings which were inspired by the works of mKhyen brtse, reflecting the influence of the mKhyen lugs school of painting as far as the 18th century.

1. The Art of mKhyen brtse dbang phyug at Gong dkar chos sde (Gongkar monastery)

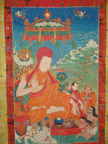

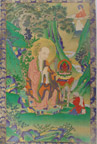

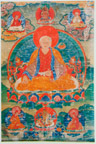

Fig. 1aThe most exceptional murals of this monastery are those by mKhyen brtse chen no dge bsnyen rnam rgyal, often called mKhyen brtse dbang phyug, who was born around 1430 in the region of Gong dkar. According to the biography of the rDzong pa Kun dga' rnam rgyal (1432-1496), founder of Gong dkar monastery, mKhyen brtse fully understood the painting schools and styles of India, China, Nepal and Tibet.[1rDzong pa kun dga' rnam rgyal rnam thar by rGya ston rin chen dpal, edition of 2001: 173, lines 6-13.] From the time he was small he studied the arts, first observing and studying animals and flowers as his subjects, and then as his studies advanced, he went to gTsang where he studied with the master painter rDo pa bkra shis rgyal po, who had personally studied with sMan bla don grub. Not long afterwards, he had complete mastery and left his teacher. As his root lama was Kun dga' rnam rgyal of Gong dkar rdo rje gdan, he went to this monastery to do paintings here. From 1464-1476 was his first phase of work there, at the time of the foundation of Gong dkar, where his own talents really emerged in a style previously unknown. He did both sculptures and paintings although at present only the mural paintings are extant at Gong dkar.[2See below for the remarks of Ka Thog Si tu Chos kyi rgya mtsho, who observed both paintings and sculptures by mKhyen brtse during his travels in central Tibet in the early 20th century.] His fame spread very quickly, and it was said that he and sMan thang pa sman bla don grub were the two most extraordinary painters alive. In the Gong dkar Assembly hall which was 64 pillars in dimension he painted the Ston pa Yang dag pa rdzogs pa -- the series of the Acts of the Perfect Buddha. On the north side of the monastery, there was the large Protector chapel, measuring 4 pillars, and here he painted the murals of the visions and protector deity manifestations of the cemetaries. In the temple called the Dri gtsang khang, of four pillars, on the walls he painted Dipamkara and the Buddhas of the Three times (past present and future -Dipamkara, Śakyamuni and Maitreya), as well as the Seven Buddhas of the Past.

Fig. 1bIn the Dri gtsang khang, there was the lineage of the Sa skya masters of the Lam 'Bras (Path and Fruit) tradition, large scale portraits of the Five Great Masters of the Teachings (See Figures 1 a-b). On the right wall are the Three White Masters were all laymen: Sachen Kunga-nyingpo (Sa-chen Kun-dga’ snying-po, 1092-1158), Sonam-tsemo (bSod-nams rtse-mo) (1142-1182), and Dragpa-gyeltsen (Grags-pa rgyal-mtshan) (1147-1216). On the left wall, the Two Red Masters were monks: Sakya Pandita Kunga-gyeltsen (Sa-pan Kun-dga’ rgyal-mtshan) (1182-1251) and Chogyel Pagpa (Chos-rgyal ‘Phags-pa) (1235-1280), all surrounded by other members of the lineage on smaller scale. Then on the circumambulation corridor, there were the 12 Great Acts of the Buddha Śakyamuni.

On the south, it was the Great chapel of the Tantric teachings, also called the Vajrabhairava chapel (see figure 8, detail of mural of Vajrabhairava), which had two pillars, where there were also fightening cemetary scenes as well. There are also other meditation deities such as Kalachakra and Guhyasamaja (See Figure 8-b) and a special aspect of Vajrasattva (Figure 8c). On the next level, there was a chapel with 16 pillars dimension, with the Guardians of the Four Directions. In the protector chapel (mgon khang) which had the dimension of 6 pillars, there were wall paintings of Sa skya pa chen po and great siddha such as Virupa (see Figure 4a), as well as cemetary scenes (see Figure 4-b, 4c) and deities such as the Yaksa accompanied by the 8 horsemen (Figure 5) and Jambhala as the God of Wealth (Figure 6).

Fig. 2a |

Fig. 2b |

Fig. 3a |

Fig. 3b |

Fig. 3c |

The Hevajra chapel has 4 pillar dimension. Dedicated to honour Hevajra as the principal meditation deity of the Sa skya lineage, there are several murals, notably of Vaiśravaṇa as guardian and god of weath (see Figure 7), as well as murals of the cycle of Hevajra and the 9 gods according to the Sa skya liturgy of the rGyud sde kun btus (see Figure 9, detail from the Hevajra mural). There is also a small 4-pillar dimension Chapel of the Lineage of the Path and the Fruit (the Lam 'bras chapel) which has murals of the Buddhas of the Vajradhātu and Maitreya and the 996 Bodhisattva.

As of 1472, there was the construction of two additional chortens and mKhyen brtse was invited to Gong dkar once again. In the 20th century, these paintings were all described by Ka thog Si Tu Chos kyi rgya mtsho in his guide to the Cultural monuments of dBus and gTsang[3Ka thog Si tu, Guide to the Cultural Monuments of dBus and gTsang, edition of 1999: 127 and 132; Here Ka tog cites the Golden Garland of Kagyu teachings.], and he mentioned a thangka of the Golden Garland of the Teachings which was attributed to Mkhyen brtse as well.

In the Water-female-pig year, of 1503, the 4th Red Hat Karmapa Chos grags Ye shes invited mKhyen brtse to Yangs pa can monastery to decorate the walls of the principal chapel[4dPa' bo gtsug lag phreng ba, History of Festival of Scholars, edition of 1986: 1148] and this was very successful.

Again, following this period, mKhyen brtse was requested to return to Gong dkar rdo rje gdan by his root lama Kun dga' rnam rgyal, where it was said that now mKhyen brtse was the only great painter alive after the death of the painter sMan bla don grub. It is thanks to the biography of the founder of Gong dkar, his root lama Kun dga' rnam rgyal that we have information about his activities spanning from roughly 1430 until 1500.

2. The particularities of Mkhyen brtse's painting and the characteristics of the mKhyen lugs

It was the Fifth Dalai Lama who described the characteristics of the school of painting known as Mkhyen system in his autobiography (see the Dukulai's gos bzang , vol. 2, 176) when he commisioned a set of paintings of the mandala of the Vajravali and stated that the thangka of mandala cycles and also those of the wrathful deities when well painted were to be made following the Mkhyen school, while the peaceful deities when well painted were following the school of sMan bla don grub. He had often visited Gong dkar monastery personally, and knew well.

As for the distinctive characteristics of this school of painting, one may find in the Dukhang, the wall paintings of the Avadhana series which depicts 100 former lives of the Buddha which were exceptionally well done, with special attention to details such as trees and plants. One may count as many as 65 different species and forms of leaves (note leafy green tree in background of the Buddha, behind the throne, in Figure 2 and the very different tree in Figure 4 from the mgon khang.[5Yangs pa can, The Wall paintings of Gong dKar, pp 150-151.]

Also in these sacred scenes of the lives of the Buddha, there are the tigers, the makara, the crows, and the presence of so many animals and creatures, this was one definite particularity to be observed in this paintings by mKhyen brtse, for some of the creatures were playing, some were weeping, some were pointing and others were harmoniously in groups, with range of activities and expressive features (see Figure 3a and Figure 3b for the tiger and note the wolf and jackal in Figure 4a).

Fig. 4a |

Fig. 4b |

Fig. 4c |

Fig. 5 |

Fig. 6 |

Also, for example, in the painting style of the earlier master Byi'u sgang pa, there are the haloes and the throne backs which are in a particular style, while in the mKhyen brtse style of the throne, it is the wooden frame, where the brocades and bolsters which are absent, as may be seen in the Buddha's throne of the mural painting in the Assembly hall (Figures 2a-2b). This same shape of throne and the lack of textiles persisted as we will see below in our discussion of the paintings of the later followers of mKhyen lugs. For the halo, one may remark the distinctive circular shape of the halo with garland surround in the portrait of Sa Chen (Figure 1a) and bSod nams rtse mo (Figure 1b). We find this same pure circular shape, where the outer edge of the halo is rendered in a dark pigment, almost as an outline of the radiance of the halo (see this feature in the detail from the Hevajra mural, Figure 9, as well as the Buddhas of the assembly hall, Figure 2a).

Also the facial features of each of the great religious masters are highly differentiated, it is not a standard portrait face but very individual features, whether for the portraits of the mahasiddha Virupa in the protector chapel or also for the portraits of the great religious founders of the Sa skya lineage.

One may also remark the special cemetary scenes both in the Protector chapel and in the mgon khang, and in the Yamantaka chapel which are certainly some of the most remarkable paintings of the entire monastery due to the very nuanced application of alternating opaque and translucent colors on the dark walls. The haloes of fire are stylized and vivid, with long flames of many tones of red, yellow and black. One must also call attention to the fact that there is also a special scale of painting, based on mKhyen brtse's individual finger size, which influenced the scale of the actual painting.

There is also a tremendous expressive quality to the facial features of the deities, particularly the wrathful facial expressions which are visible in the faces of Vajrabhairava, Figure 8, where the great attention to details such as the minute dotted outline of the flaming mustache emphasize the mouth with its realistic fangs of different height, while the eyes are emphasized by similar treatment of the flaming eyebrows. The flames surrounding the wrathful deities are also painted with great attention to detail (see Figure 9, goddess of the entourage of Hevajra) where also the face and body of the goddess exhibit this quality of attention to fine detail and also we find there is great skill in the proportions of the body, which are beautifully rendered with shading and deeper or pale color nuances to model the volume of the body.

Fig. 7 |

Fig. 8a |

Fig. 8b |

Fig. 8c |

Fig. 9 |

In the Assembly hall, the robes of the Buddha also are painted in a very distinctive manner for the robes which are many different types - some short and some long sleeves, while the actual cut of the garments and the realistic treatement of the fabric leads the robes to drape over the Buddha's body in an unusual manner (see Figure 2a and Figure 2b).

3. Examples of the mKhyen lugs school of painting

Today in Tibet some of the paintings by mKhyen brtse and his followers are to be found in the place where they were created, such as at Gong dkar, while other portable paintings have traveled far from their place of origin. The primary region is the two regions of Central Tibet, dBus and gTsang, and also during the 15th century, in the Lho kha region, particularly the site of Gong dkar. In the 17th century, in 1615, Jonang Taranatha founded the Phun tshogs gling monastery in Lha rtse region of gTsang, where there were mural paintings in the mKhyen lugs school.[6Dung dkar blo bzang phrin las, Dung dkar tshig mdzod chen mo, 2002: entry 2330.] In 1654, when there was the commission of mural paintings for the Assembly Hall of the 'Bras spungs monastery in Lhasa, the Great Fifth Dalai lama commissioned these paintings following the style of the paintings by mKhyen brtse in Gong dkar, notably today there are the paintings of the 16 Arhats in this Assembly hall. [7Fifth Dalai Lama, Autobiography, edition of 1991. 443.] In the 19th century, in 1890, during the period of the Demo srid skyong 'phrin las rab rgyas, there was a conservation and restoration project for certain paintings of the 15th century in Gyantse (rGyal rtse), in the the dPal 'khor chos sde gtsug lag khang where certain stylistic characteristics of the mKhyen lugs school were apparent, such as the perfectly round halos of the Buddhas (see Figures 10 and 11) [81998 (6): 66, annals of 1890 for Gyantse prefecture (in Chinese).] , which may also be observed in this 19th century thangka of National Palace Museum (Figure 12). Furthermore, in the prefecture of lHo kha, at the sMin grol gling monastery, there are also mural paintings of the mKhyen brtse school. There were many murals, more than 500, but unfortunately there has been damage due to natural elements (hail, water damage) which has impaired the condition of the pigments, or in other cases, the very plaster of the walls is damaged.

Fig. 10 |

Fig. 11 |

Fig. 12 |

Fig. 13 |

Fig. 14 |

There are also many thangka which were made in the manner of the mKhyen lugs school of painting. In Gongkar monastery, there is a thangka of the Sa skya protective deity Phur ba Vajra kumara (see Figure 13) and also thangkas of the 17th century which show hierarchs of the Sa skya lineage (see Figure 14) such as this portrait of Sa skya Pandita which is a later version of the mKhyen lugs style, still retaining the perfectly circular halo of the original mKhyen lugs, but in the 17th century, the circular halo is now outlined in fine gold line; the very delicate and individuated facial features are retained, while due to the change in scale, there is even more emphasis on the facial features and the highly differentiated hair styles. Now conserved in the Tibet Museum in Lhasa is a thangka of an aspect of the White Tara which is also in this later style of late 17th to mid 18th century which is strongly influenced by the original stylistic grammar of the mKhyen lugs school of painting (see Figure 15), for the perfect round halo, again translucent but with the gold outline, the profusion of leaves of many shapes and many shades, and also the distinctive throne with wooden frame of the lama in the lower register, totally lacking voluminous silk bolsters or cushions and draperies. (see Figure 15a). The series of thangka of the 'Brug pa bka' rgyud pa also reflects this later period of the mKhyen lugs school of painting (see article by Amy Heller in this volume).

Fig. 15 |

Fig. 15a |

Fig. 16 |

The wooden frame throne model may also be observed in the thangka portrait of an unidentified Sa skya teacher, now conserved in the Rubin Museum (see Figure 16).

In the 17th and 18th century, also at Sera monastery, there was a series of thangka of the 84 mahasiddhas, while in Beijing, there was a series of the 16 Arhats inspired by the mKhyne lugs school of painting, now conserved in the National Palace Museum (see FIGURE 17 a-b-c-d). In the Rubin Museum of Art, there are other clear examples of the Mkhyen lugs influenced thangka, notably the portrait of Sa chen Kun dga' snying po (see Figure 18) and the very delicately exectued thangka of the meditation deity HEVAJRA (Figure 19).

Fig. 17a |

Fig. 17b |

Fig. 17c |

Fig. 17d |

Fig. 18 |

Fig. 19 |

To conclude, this is but a brief introduction on the work of mKhyen brtse dbang phyug, the mural paintings and thangka which evidence his personal style and those which reflect the long lasting influence and impact of his exceptional mastery of the brush. It is hoped that the illustration of these paintings allows a better understanding of the stylistic features and aesthetic grammar of the Mkhyen lugs school of painting.

* Translator's note: This article is a revised version of Penba Wangdu's research on Mkhyen brtse, first published in Tibetan language, without illustrations, in Journal of Tibet University, 2010, 4:112-117. Although readers may be familiar with the term mKhyen bris, which refers to mKhyen brtse's painting style, throughout this article Penba Wangdu uses the term mKhyen lugs, the mKhyen brtse aesthetic, which refers to his style in both painting and sculpture, as he was a master of both media.”