Articles on Indian contemporary art by Swapna Vora

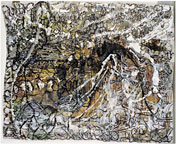

August 31, 2007 (click on the small image for full screen image with captions.) "Long ago my grandmother used to tell us stories. One had two birds in it. They were observers alongside the story. The prince did this or that and the birds would express their view: Will this be good for the prince? These are the stories unfolding in every island of my paintings. We experience various islands, but we are not this island or that town or that cave. We build separate islands, which we visit but which are not us. Today we are here, then there." "A Kolkotta marsh has become a modern city, a township. It used to have big fish, tall grasses, many insects. Now there are buildings. Where are the birds, the bees, the hives? Where did they go? This I put in front of you, on one plate, where I build the painting. How I saw my little place grow! Is it growth, progress or what, something else? The two birds discuss, they are 'sakshi', (witnesses). This is where I question myself, my observation, my stories. I am uncomfortable, tremendously uncomfortable with both comfort and discomfort." Jayashree Chakravarty's work is very detailed, unbelievably painstaking and full of stories, memories, and images from childhood, from her many travels, and her schooling in India and France. Listening to her entrancing thoughts, her adventures or tragic events is like being with Sheherazade. One folded line, a pleated memory, an ironed patch of blue bring recollections of her doctor father, another makes her say, "I need to go back to Kolkotta soon." A big series of ovals grow into the lines on ECG reports. Some faces and some keys in these maps remind her: "Sitting by the bed, those are my friends who loved him and visited him for advice even when he was so ill." "I try to paint and remain true to my understanding, not just emotions or feeling, but understanding. Understanding is very different from simply feeling something. Every bit, every image returns. I need to concentrate very hard when I paint." "This imagery changes shape, color, everything. It starts here, it exists somewhere. I never know what I will be doing. There are no painting plans, I love exploring this peculiar journey, it allows me to enquire, to investigate. This demand of the canvas, I try to fulfill it. This communication keeps me going. I am dead without it." The chateaux suspended in her work? "When I leave Kolkotta and go abroad, I always get a map and take it wherever I go, so I know where I am. I go alone, so this helps me to get oriented. This work is my language, my diary and my reactions. If I am true to myself, I let it arrive spontaneously, a flow, for I do not know what I want. Ultimately something takes place and I paint it." "I never decided to become a painter. I was a flibberty-gibbet child, who could not still sit still except when she painted. My dad encouraged me a lot. When I had to specialize in school, I chose science and much later said, 'I want to paint.' My parents were happy and helpful, especially my dad. They encouraged me every way they could although my mother kept hoping that her two daughters would become doctors like their father, or at least one should follow him." "I come to New York often since '89. Today Betty Said has curated my work here. It is a paper installation that you enter. It is made of the same paper that I paint on, layers of paper, a layer of cloth and then layers of paper. It takes a year and half to finish each painting and I do about 14 at a time. I use layers and leave them alone to dry and then return as memories of my journeys and stories arise again. "I am alone, very alone. So I can visit these places, think and bring all that to my work. All that becomes very clear to me. I am going through this but I am not that, instead I am like this. These are my memories. There are no statements, no feminism, no fights nor political statements. The places I visited, how they were, how they have changed. When something started, I did not see its beginning, I had to imagine that. I see it today and know only how it is today. "My life, I go through it. My parents are old and I see so many medical diagrams - so many lines of ECG. As a painter, I react to lines. Lines are very meaningful to a painter. Does this dip mean illness? Here a line is a word or a stroke, very vital, it conveys something. These lines take me to a different thought process. I paint a part of the brain and then a huge beetle, my imagination goes there. Our thoughts are eaten by so many counter thoughts, so many insects!" Her work has layered images, uneven sheets of colors, and even black and white pats. "I often have ten layers, and for every layer I leave a gap of 2 - 3 weeks. Then I may apply the next thick layer. This is difficult for the next layer has to sit on it. This requires passion, concentration. My travels encourage and inspire what I have done and those stories are or could be the meaning. Five simple lines on a space can convey meaning and my images accept this meaning." "Recently in London I saw gorgeous work, with amazing strength and weakness. When you see such dazzling work, you see a very good work of art, and you know where you are. I understood the quality of these paintings after I myself had done so much concentrated work." Going across to her paintings, we see some uneven oblong shapes. These, she explains quietly, were on the ECG reports, and each line emerged from them as it conveyed its tale of a beating heart. "If you only read something, you do not write about it in your language, do you really know anything about it ? Whatever I see, I am writing in this language. This language, of course, is called art. What I receive, I write." Jayashree has an innocent face, soft clean skin, and eyes ready to turn away. Her father's death lingers around her. "I am silent. In life, certain things become loud. When does something become big? And two months later it is not so big. When he left me, this feeling, this event covered everything. There was no space in me, around me, where it did not reach. I need to explore that. Certainly this enveloped my mind. I do not know if I can do it, understand it. A kind of meditation, this process of painting." We see her painting of a spider and a fly, and see many insects. "We are drawn to beauty even when it is dangerous. I enjoy blue now." "Whose work do you enjoy?" She says "Anselm Keifer, Da Vinci", and smiling shyly. "Do I dare use such a big name? Van Dyke. I love Husain saab's early work, Arpita Singh and Souza." "Such sad work?" I counter. "Yes", she said, "Sad. And potent." "My work is untitled work. I work with maps, very stimulating." We examine the lovely white concentric circles on her painting. "The circles? Where I go, I need a map as I roam alone. North or south, the journey, the air pressure impressions, (the isobars), the map. I give no name to this painting. You may", she says generously. Her mind and this concentration remind her there was a disturbance there, here were insects. I query the twinkling spots in one painting. "That is the sky with twinkling stars above my face, twinkling stars. My paintings are never complete. They, the galleries, the buyers, say it is complete. It is not. I'll change it next year and galleries sigh when I want to redo something." She smiles and shakes her head at their incomprehension. "I make my paper. It has layers of paper, then cloth, then paper. It takes time and it is very strenuous physically. It is a little uneven. I make it in my house. It takes huge areas of space. This becomes like 'chamda', the skin." Jayashree originally experimented with paper when canvas was too expensive. We visit another painting: "This is the brain, the ECG lines I had to read, the small rubber hose is here. I wrote words on it and then blurred them. I saw my aunt, so vibrant, so alive become a vegetable when her brain changed. The bird is eating these lines of illness, because ultimately nature will heal us humans. Underneath this, my meaning is we are going away from nature, too far, much too far. Nature takes away tension, all illness." She loves Europe's maps. Palimpsest, I say. She laughs delightedly, "Yes, that is what my paintings are. My mind traces and I see the layers in the country of my mind. This is a journey to myself." She then spoke of Michael Anderson, a Commonwealth scholar, and said he knew her work and he knew her growth for he had seen her work over many years. She speaks of the salt lake in Kolkotta. "When I left childhood, I grew. All these adventures, emotions, understanding." Underneath it all, she points to water in a painting: "The water bears my weight, keeps me floating and the fish lives in it so comfortably. I hear, I wish, I imagine." "I used to pray, please give me some knowledge and one day it arrived. It was delivered. Without reading, from somewhere in my being, it arrived, I could understand." Her paintings show impressions of memory and are a war between what happened and the new things that happened afterwards and the even more things, more events, more memories which followed swiftly. She draws both lush and spare terrains, both little houses and grand chateaux, insects and brains, sedimentary memories metamorphosed into gneiss, heated, chilled, perhaps forgotten, remembered perhaps incorrectly, for memory has its own reasons. Stories, then, are what memory has sieved not as they were but as they became. The thin fabric and rice papers of our lives. "Many starting points will do. I stare at my work and then the seed changes. When I travel, every step leads to another horizon. I enjoy the fact that there is 'such a lot of world to see'. My painting is a vessel for my memories, a holder of events and places, a house full of people. Through meditation the body becomes light, the taste changes. A force comes out, as the flow, the wonderful flow starts." A huge statue floats in her painting, and she recollects the huge Jain statue of Bahubali at Shravan Belgola in south India. She treats all her experiences as wonderful, as thoughtful, as if life matters, "where every thing is equal until it recedes, until it emerges." When all can experience the same, every thing is here all, and then all experiences become sacred. Is the unconscious our true condition? An innocence, childhood, deeply loved parents are recurring Indian themes in her work. Remembered experience, a child's view of houses, a text on zoology: this is not random rendering of work but difficult, sophisticated techniques, as she shows minds full of beetles or a swan (hunsa) which is often used as a symbol of wisdom, a play on its syllables 'hun' and 'sa', the sound of breathing. "I cannot imagine the end result so I prefer not to show my painting until I have finished, at least for now! Geography does not matter because the center is where my home is." Each mark and layer has many meanings to her, perhaps fish, flowers, faces, words or something that somebody said. "Can't say tomorrow I'll finish this painting. Yes, you can finish it but there will be no life in it." We speak then of 'Pran prathishta' for as she says, "You have to put life into it." Tripura,

Assam, is her birthplace. It has a strange fascination for Hindu

minds, for it is the city of Shiva. For us urban types, it is

almost legendary. It is far off in eastern India where Kali is

affectionately loved, where time had meaning, where women were

powerful. Assam has a climate of soft green hills, mekhla saris,

a town of deities where Lord Shiva established his power again

and again.

|