Kanwal Dhaliwal

Immigration

By Swapna Vora

December 15, 2010

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

Immigration: Some countries live on it by getting the best brains or brawn in the world, by simply giving them nationality and a place where they can explore and exploit their talents. Others forbid it, afraid. Some make anyone who leaves pay for all the education and food received when living there. Still others are happy to have our work but not our presence: one must pay taxes but cannot be a citizen. Sometimes we own land long before a land owns us.

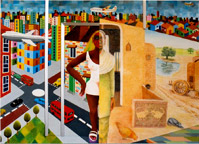

Kanwal Dhaliwal has drawn, sculpted and painted the many themes of immigration, the country one grew up in, the country one learned to call home where everything looked the same and nothing was familiar: Homes with shoots but no roots, horizons of fool’s gold glimpsed while traveling, children who speak a strange language and look at you as if they do not know you, new bugs, new officiousness, strange climates (figs. 1, 2 and 3). Often immigrants think of killing the past, of beginning afresh or of adventure, not that this too is an end. Many manage to forget they had to jump ignominiously through the eye of a needle and the thousand days of waiting. Meticulously, with deep introspection, Dhaliwal brings these sometimes vertiginous experiences into forms where we too may remember and reflect.

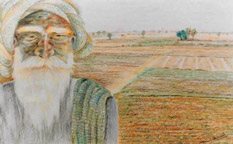

Fig. 1. Drawing |

Fig. 2. The Immigrants |

Fig. 3. The Roots-2 |

His paintings when exhibited at Hounslow, UK (where he lives) elicited this comment repeatedly: “You have shown what we felt but could not express”. Hounslow is an area populated mainly by Punjabi and Sikh immigrants, very near Heathrow airport, right where they first landed when the UK offered them jobs.

Another recent series consists of portraits. He shows the writer Saadat Hasan Manto. Partition had shattered Manto’s world and he angrily suggested that since seemingly sane people were moving across the new British created border between India and Pakistan, surely all the mad in asylums should also be moved to new homes. Dhaliwal drew Gehal Singh Chhajjalwadi with his dismembered torso, Amrita Pritam on the backdrop of her poem on partition, and Udham Singh with his forbidden statement. (figs. 4, 5, 6 and 7)

Fig. 4. The Thunderstorm |

Fig. 5. The Victim |

Fig. 6. The Poem |

Fig. 7. The Statement |

When did you become a painter?

Dhaliwal grew up in the Malwa region of the rural Punjab. His background was all about the countryside, the seasons for planting and harvesting wheat or mustard, tractors, bullock carts and the stark white hot summer light contrasting with the dark, much desired shadows. He was born in a village and brought up in Malout, a small town, with friends, neighbors and many relatives: a life full of relevant, related folk. His doctor father exposed him to literature and language as he studied at the local school. He absolutely loved art classes and did casual light artwork for himself. “No one there knew that you could actually study art, that it could be a profession, that one could be educated to be a professional artist”, he says. “Suddenly one day a family friend from the capital city informed us about an Art College there. From that moment I knew that was my life. I was going to take the maximum training and education available in that line. At the time of admission I was asked what sort of art I wished to pursue. I was surprised because I did not know there were different types, different possibilities.” ‘Different brands’ as Dhaliwal puts it.

“I just said painting, for I didn’t know anything else.”

“They looked at my work, liked it. I chose painting, a five year degree course, and got my BFA. In the evenings I studied Russian. I had already read Pushkin, Gorky, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov etc. in Punjabi and Hindi and really longed to read them in their original language. So I painted during the day, studied Russian in the evenings and got a diploma in Russian at the same time. I was recommended to India’s University Grants Commission and received a letter from the USSR embassy that I had a visa I hadn’t even applied for. Maybe they just liked my interest in Russian! I had started teaching art in a local institute. I left the job and moved to Moscow for a year. I met sculptors there, all sponsored by the state. One artist let me work in his studio. Unofficially I had access to a studio and even had an exhibition.”

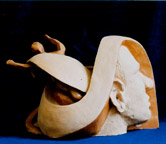

“I could not separate art from language and creativity, their various relationships. When I returned, I looked for proper qualifications and got my own studio at home but I felt I was not fully utilized. I joined the Hyderabad institute for foreign languages and did a three year correspondence course. (This was before the internet and instant access to other languages!) Since I had spent a year in Moscow, I already knew the language and its pronunciation. It was a very strict three year course at the Institute of Foreign Languages, CIEFL but I got top grades. I really loved it there. One teacher Ms. Kamakshi Balasubramanian, taught me to love Chekov, his satire. I loved him. She saw something in me and advised me to go abroad. I had been busy, painting full time, studying Russian and teaching.”“Next I got a government job teaching art. I really needed it as I wanted to support my parents. They too were getting old. Getting a secure job at Chamba, Himachal Pradesh, my ‘first choice’, was like hitting the jackpot. I was very lucky to work under Mr. Subhash Rabra who understood art in its true sense and didn’t consider me a mere signboard painter as many headmasters do. I was teaching, painting amidst the unique Himalayan landscape. I saw stones and started carving sculptures. (Fig. 8) Local master craftsmen taught me beeswax moulding and metal casting. (Fig. 9) Life was a bird’s flight when it hit the rock!”

Fig. 8. The Village-14 |

Fig. 9. The Folk Faces-2 |

Personal life interrupted this: loving a colleague from another religion and caste. “She was taken away and brainwashed by her fanatic parents, who had political connections. I realized my case was hopeless. In spite of rising professionally, I felt bewildered, disillusioned, embarrassed, humiliated and wanted to get out. A marriage proposal from the UK arrived! Eager to get out, without much query, I fell into another trap. I arrived and the woman made it clear she wasn’t expecting me and had done all this to please her parents! Somehow during these troubled times I got myself together and kept expressing colors and lines. Life was not just misfortune! After a year or two I came across my life partner. ‘Third time lucky’ as Nirupama Dutt, a poetess friend, wrote in her article. My life really began at 40!” Kanwal now has two lovely children aged 8 and 5 and “a future full of opportunities”.

“History is my passion, I want to know what happened and why. In London, coming across ‘familiar’ words in ‘unknown’ languages, attracted me towards reading about the Indo-European connection in the linguistic past. Next I got interested in the study of genetics and inherited genes from the earliest evolutionary forms like fish to wherever we are today. I became a fan of Darwin and (Richard) Dawkins.” As can be seen from this, Dhaliwal really is very efficient, with a talent for living: a hard worker, very thorough in following up his interests. Currently he paints all day, holds a railway job, runs his house and manages the children as his wife works full time.

Coming from the rural Punjab, renowned for its farms, it was inevitable he felt the need to touch the soil and grow things. He said, “My children know all about agriculture and follow my interest in palaeontology and anthropology. I found them trying to find fossils in my suburban plot! So we went to the south of France to see the caves at Les Eyzies de Tayac (Lascaux area) and early man’s art. Again a genius, Mr. Jean Durin, a retired professor of ‘Russian Grammar for French speakers’, a scholar on ‘figurative stones in prehistory’, and an Auschwitz victim’s atheist son, invited us to visit locations and museums on pre-history. He is a friend from my Moscow days.”

I said, “You have access to all sorts of wonderful art material in London.”

He said, “Yes, but I like the brushes here (in India).” Many artists buy hundreds of brushes here especially in Jaipur. Typically Indian, he gratefully and lovingly acknowledged his guides: “My mentors guided me, especially Professor Lally. No one knew his real name, Hardiljeet Singh Sidhu, a lecturer in anthropology - linguistics at Patiala university. An amazing intellectual, he could give stimulating lectures all night. He was so energetic, he was the last to fall asleep. He familiarized us with modern fiction and every art form used for creative expression in the contemporary world. So much we did not understand, but felt that whatever he said was something so vital, something so important.”

“At the Art College, I studied certain topics and themes. We had to study drafting as required in engineering and without it we would have been failed.”

“They were ensuring you were employable?”

“No” he disagreed. “They emphasized completing the syllabus without any foresight into how this acquired knowledge would give us a living.”

“After two rigorous years, we finally had some freedom with our art. Then”, he continued, “I started the Window Series.” He just took one window and made it represent humanity’s civilization and nature which brushes past it. So we see one window, one branch, and the dark and burning lights.(Fig. 10) (This was reminiscent of Hesse’s wild, nomadic Steppenwolf, who looks at a neat suburban window with its lace curtains and flowering geraniums.)

Dhaliwal started composing his first series with different thoughts, different angles and light. “I really took off after that. My mentors were senior artists who always emphasized local culture, local spaces and said, ‘If you want to make something unique, go within.’ This view was strengthened by seeing works by Amrita Sher-Gil, the only artist I admire from the modern era of Indian art.”

“Then I was looking at works by other artists, some bygone. I was surprised that sometimes I could not make out their origins, if they were Western or Indian. This perplexed me. Was this artist Indian or British? This was not a restriction but it amazed me that this could not be seen, it was not apparent. With that thought, I painted and sculpted village scenes for ten years. Then I felt this was too vast a theme, too vague. It was a whole world, all kinds of people.”

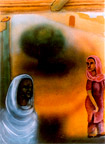

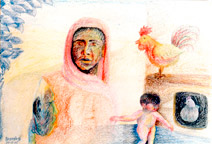

“The deorhee interested me, an outdoor indoor space, a connection of the house to the outside world. (Fig. 11) The word ‘deorhee’ is connected to ‘door’,” says Dhaliwal the linguist. In hot climates this space is important, especially to connect with other people and happenings in the village. “My aunt and my village inspired me. My aunt talking to the folk next door, the deorhee’s entrance to the road, the goats or hens which sometimes lived there, a tractor parked there for the night, jute mats and always a charpoy.” (A string bed on four legs, also used for sitting and chatting.) The animals were, of course, treated as part of the family, talked to, played with, patted by the grandmother. Hens, cows, flapping wings, farm implements! (Fig. 12)

Fig. 11. The Deorhee-2 |

Fig. 12. In the Deorhee-2 |

Fig. 13. The Courtyard |

“During the day, this was the women’s room, a connection with the outside world. News of both death and birth arrived here first. I used to sit there and pretend to be very studious but really, I was listening to them, a witness observing them. Later I took photos, slides and studied them for inspiration. The whole world existed there.” A doorway led to the village, the walls were shared with next door folk. The decorative almost window-like gaps in these walls meant one could certainly look into the neighbor’s deorhee, probably catch sly glimpses! A different concept of privacy? (Fig. 13)

“I concentrated for ten years on this space: the women’s faces, the architecture, the landscapes just outside. Landscapes, scenes, people all three merge into faces. All were separate but I merged them into one.”

The deorhee is a kind of entrance hall, a room at the threshold, with perhaps two walls. “Same as in the Golden Temple at Amritsar, the Darshani Deorhee gives you a glimpse of the temple before you venture further. I still feel there is so much more in the deorhee, the rural Punjab. I feel I have painted just the tip of an iceberg.”

“First I drew but felt ruggedness and roughness came in better with paint, pastels and soft colors. Artist friends loved my work and found it ‘very solid’. I felt inspired to sculpt though I was not trained in it. I taught myself every medium I could find.” (Fig. 14)

Dhaliwal draws faces of the rugged farm folk with his very capable looking hands and long, beautiful fingers. He has done several ink and wash works while exploring the sharp Indian sunlight and the really dark contrasting shadows.

His faces, done like landscapes, are more apparent on males. The land and their lives are really intertwined and this is reflected on their faces: human faces distorted sometimes by deprivation, by lack of good living. He mentions that lack of teeth, information and resources makes the poor dreadful looking. (Fig. 15) (India went through several generations of food deprivation when all grain was forcibly taken and shipped off, for example by Churchill and others to Britain and to their various war fronts.) History after all is reality which not many can endure or even dare to examine.

Dhaliwal said that execution is not difficult, once the image is clear. “Sometimes the idea remains in the abstract and then I need a form to depict it.” This is of course what artists do. His trees are so dense and leafy that they look dark in broad daylight, with thick shadows underneath. He draws universal faces, Punjabi women, roosters, babies, chickens, perhaps a cooing dove.

He had an exhibition for rural folk and said they really appreciated it. “This is it”, they exclaimed. “I felt I had caught their spirit. Out of the hundreds of comments, this is what I really remember.” “Our landscapes”, (Fig. 16) the farmers said when they saw his work.

In the hot weather, dogs lie in shadows and around 11 am women carry food to farmers who have left their homes around 5 am. Everywhere, he continues with the same age old, peasant faces. He shows the traditional angeethi, oven-like cookers built in walls, much prized for careful, slow cooked food like black dal or milky sweets.

His series, ‘The Village’ spanned ’85 to ’95. With characteristic thoroughness and really deep delving into the heart of things, he says he understood the theme but changed the subjects. Now, leaving women aside, he began to examine men’s lives in villages and small towns and introduced their faces. “I wanted a spot to observe quietly, from where I could see lots of male faces. I was lucky I found this easily with a lawyer brother in the small courts in rural areas. I never disturbed him, his legal colleagues or their clients. People came to see the lawyer, discussed criminal cases, murders, land disputes. I also went to his colleagues’ offices.”

“What did you see?”

“Their total absorption in their small worlds, so very important to them, a matter of life and death. Small cases are so huge for small people. (Fig. 17) I took lots of photos but never disturbed them. I was working on this series when I migrated to England. I could not stop suddenly, so I revisited India but lacked continuity, lacked relevance. I always work around what is around me, that is my inspiration, what I see around me.”

Fig. 17. At The Advocate-1 |

Fig. 18.The Clients-1 |

Fig. 19. The Clients-2 |

The lawyers’ clients were mostly white bearded peasants and farmers. (Fig. 18) “They did not mind me.” I spoke then of peasants, often illiterate, who do not know the law, get pieces of papers waved in their faces, mountains of papers, and their dependency on solicitors who often listen to dozens of cases at one time. There is public discussion of cases in lawyers’ rooms with many unconnected parties listening. Alongside bewildering landscapes, roomscapes, and lawyers’ things in sheds, Dhaliwal’s peasants too sit in their allocated spaces. The walls have the usual pierced windows to let in light and air. (Fig. 19)

He spoke then of the communist movement in Punjab. “My father was sympathetic to the socialist cause but never joined any political party. He remained loyal to the reforming zeal of his inherited faith - Sikhism. I do not believe in any religion or in the concept of god, my parents did not mind.”

Dhaliwal was now working with colored pencils and pens. “For particular expressions, I used colors, perhaps blue or green faces, to show moods, worry, and perplexing situations. There were many legal clients at one go for private and public events merged in the old country. When I migrated, I lost touch with this world. I stopped painting it intentionally. In the UK, other experiences, influences came in. I thought again, what should I paint? I could not justify continuing the old series when I was elsewhere.”

Next he started his ‘Dilemma’ series, showing uprooted trees, torn roots, trees which look full and flourishing but lack roots, with big gaps between them and the earth. He shows split personalities who wonder where they are, why, and how. He shows Punjabis and the traditional dupatta on a woman’s head becomes a river of freedom. (Fig. 20) He mentioned the old Punjabi saying about a snake with a poisonous lizard in its mouth, every way you look at it you lose. “Can’t eat it, can’t leave it, for it will bite.” Dangerous either way, to go or to stay, a characteristic of the immigrant’s dilemma.

No matter where you are, the other country seems to have all the answers. After migrating, he missed the beautiful Himachal landscapes he was used to. He sometimes felt caged and painted golden bars across innocuous scenes and split lives. (Fig. 21) Many immigrants saw his work and exclaimed, “That is me, that is exactly it.” Other did not want to know and shied away. He showed women draped in traditional dupattas and others in tight western clothes, sometimes with both sets of clothing combined in one figure. (Fig. 22) Again, he returned to showing farm people who now lived in England. When Britain needed strong labour, it had, as official policy, invited these physically strong people to immigrate.

Fig. 21. Self Portrait |

Fig. 22. The Dilemma |

The 'Roots' series followed. It says there is a lot more than what is just seen on the surfaces of immigrant lives. Immigration remains one of the hardest things people do. Today it is a little easier, there is at least the faint possibility that one could actually return, though ‘home’ has often changed irrevocably. Most Indians who immigrated did so after really harsh conditions imposed by British guns, where land, homes and even the salt people ate were forcibly taken away.

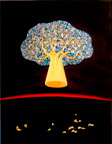

Black and white dramas, trees hidden by black light and shade are now a part of Dhaliwal’s vision. He has used thinner, finer lines for trees and leaves and the background remains hidden. (Fig. 23) He brings this work to a new generation, especially to young immigrants born elsewhere, where only their skin color is a reminder of where they came from. People who do not know their roots or where they lie can never know them except as pictures, as fairy tales, as words in languages they sometimes understand and can rarely read. (Fig. 24)

Fig. 23. The Rootless-III |

Fig. 24. The Rootless-II |

Fig. 25. The Roots-3 |

Fig. 26. The Squeeze |

He spoke of the reasons why Punjabi society had split, the rooted and rootless and the heaviness of history, bringing thoughts of our accursed ability to live essentially in the past. He showed a tree far from its roots, with no anchor, placed nowhere. (Fig. 25) He shows the squeezing of immigrants under walls made of silver bricks, symbolizing Britain and Canada. He says their originality and personality are squeezed out, all the spaces above them are occupied by blankness or wealth. (Fig. 26)

He spoke then of a major watershed in Punjab’s recent history: 1984. There is no Sikh today who does not have it engraved as part of his/her personal and social history: who did what, who was to blame, who gained, who lost. Pain is usually most unbearable when those who inflict it are known, maybe even trusted. He spoke softly about the tragedy of the Punjab which had already been invaded and divided so many times. “These pictures are caricatures of people I came across, situations we had been in.”

He depicted Punjab’s dilemma where, with the strife, people lost access to both news or rumor and simply listened to the state run radio. He said the split was the Hindus were quite happy with the Indian government’s role but many Sikhs hated it. Some were happy, some believed the news regardless that it was a lie. He showed his different neighbors: his Brahmin neighbor quietly reading papers, other Hindus listening to news, feeling sheltered while the Sikhs felt betrayed. (Fig. 27) During the curfew, no one could go out, so they listened to radios, read whatever they could and sat on indoor outdoor spaces, in doorways and balconies. Some played cards while others wept with frustration and depression. As usual, the business community and the haves and have-nots separated into groups, their concerns not common anymore. (Fig. 28) His pictures show the immensity of recent history, the barriers of glass panes and neighbors who could no longer be trusted.

Fig. 27. During the curfews -2 |

Fig. 28. During the curfews -14 |

Dhaliwal is amazing for the meticulous care with which he lives, the prodigious effort he has put into languages, linguistics, the various aspects of human migration, the hours put into refining his own thoughts and experiences and finally putting all this into tangible forms.

He drew the landscapes of our time where the gap between trees and their roots is wider, the sun is upside down, the earth’s horizon cut by a golden one. (Fig. 29) The leaves are silver and rest on gold but the cost is the loss of roots, for they are missing. He looks again at his earlier landscapes of golden wheat and mustard fields, siestas and fluttering doves. (Fig. 30)

Dhaliwal is a painter who is very definite about what his work says. There are histories, feelings in his lines and any symbol is used deliberately. This is not a painter who says, “It is up to you to find the meaning.” He says this is the story I am telling you. Happiness, he says, is saying and showing what I wanted to, exactly the way I wanted to.

Kanwal Dhaliwal will exhibit his work at The Artists Centre, Adore House, K Dubash Marg, Kala Ghoda, Mumbai between 11 and 17 April 2011. Tel: 0091-22845939

His work is curated by Chitra Ragulan, Palazzo Studio-an Art Gallery, Chennai.

Web: www.palazzoartgallery.com,

Email:

Website link for Kanwal Dhaliwal: www.art-d-kanwal.com, Email:

- An interview by Swapna Vora, Mumbai, August 2010