in the Sino-Himalayan Style [1]

by Jane Casey

June 16, 2014

text and images © Jane Casey

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

Fig. 1Towards the middle of the thirteenth century, Chinese imperial court painting typically resembled that seen in the Four Sages of Mount Shang, a work by renowned artist Ma Yuan. It was probably painted at the court of Southern Song Emperor Lizong in Linan, Hangzhou province, around 1225.[2] (fig. 1) The Four Sages are mythic figures who are said to have disagreed with the actions of a Han dynasty emperor. In order to preserve their moral integrity, they withdrew to Mount Shang where they pursued the arts of self-cultivation, thereby exemplifying Confucian and Taoist ideals. The painting’s aesthetic and its technique—masterful brushstrokes and subtle washes of color on paper—epitomise the prevailing canons of Southern Song painting.

Fig. 2Within seventy years, Chinese imperial court art also looked like the image in figure 2.[3] The painted stone sculpture, now in the Musee Guimet in Paris, depicts Tibetan Buddhist protector deity Mahakala in his guise as Gurgyi Gonpo (mgur gyi mgon po). The image is rendered in what Himalayan specialists will recognise to be a Nepalese or Newar style. This startling new imperial court style reflects the enormous social and political changes brought about by Mongol rule in China. Between 1260 and 1368, patronage of Tibetan Buddhism and its arts were one of the largest expenditures of the Yuan state, amounting to several tons of gold and silver, and hundreds of thousands of bolts of silk.[4]

This essay examines a group of Buddhist initiations paintings in a private collection. Like the Guimet Gurgyi Gonpo sculpture, they are likely to be rare surviving examples of a Himalayan-inspired school of art that flourished at the Chinese Yuan court. The style combines Tibetan Buddhist iconography and mid-thirteenth century Newar painting traditions with elements of style—notably textile and costume design—that are demonstrably Chinese Yuan. Moreover, two paintings within the group portray a Yuan Mongol emperor and a Tibetan Buddhist Sakya hierarch.

Fig. 3Initiation paintings, known in Tibet as tsakli (tsa ka li), are recognizable by their diminutive size. These measure approximately 15.9 x 17.2 cm.[5] The relatively small size of the paintings facilitated their use during private ceremonies in which a Buddhist teacher initiated a disciple into particular teachings, and more generally, in any ritual setting that required small painted images of the Buddhist pantheon.[6] Although this set of paintings is no longer complete, it is clear from the iconography of the surviving works that it was meant to serve as an introduction to the fifty-one deity Bhaisajyaguru mandala, a drawing of which appears in figure 3.[7] Often described as the Medicine or Healing Buddha, Bhaisajyaguru and his entourage are more generally associated with protection from harm, the assurance of long life, and the accumulation of good karma, wealth, and an auspicious rebirth. Bhaisajyaguru was popular in India, Central Asia, China and Tibet, but the iconography represented in this set of ritual paintings is distinctively and demonstrably Tibetan.

At the center of the mandala is Bhaisajyaguru. He is surrounded by three circles of deities and four guardians of the cardinal points. The first, innermost circle consists of seven Buddhas and the goddess of wisdom, Prajnaparamita. The second circle consists of sixteen bodhisattvas, that in figure 4 being Vajrasattva, the bodhisattva Whose Essence is as Luminous as a Diamond, here associated with the eastern cardinal point. In figure 5 is Chandraprabha (“Moonlight”) whose identifying symbol, the crescent moon, appears on top of a Tibetan-style manuscript that rests on the lotus at his right shoulder. Both figures are enclosed within golden tri-lobed arches, the background a rich red enlivened by fine scrollwork.

The third circle of deities includes twelve Jambhalas (wealth deities, see figure 6), and the Ten World Gods, ancient Indian Hindu deities who were incorporated into the Buddhist pantheon. In figure 7 is the World God known in this context as Rakshasa, seated on a revived soulless corpse. At the mandala gates are four guardian kings, represented in figure 8 by Virupaksha, guardian of the West and King of the Nagas. In figure 9 is Dhritarashtra, guardian of the East.

The Main Root of the Tsakli Style: c. mid-13th c. Newar-Tibetan Painting

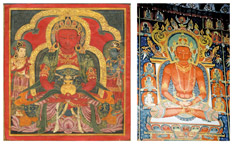

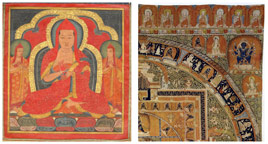

Fig. 10Important evidence as to the date and provenance of these paintings is to be found in Newar school Tibetan painting of the thirteenth century, an example of which appears in figure 10. This painting depicts the Indian medieval mystic Virupa who gestures towards the sun as he is offered a cup of alcohol by a divine barmaid. Now in the Kronos Collections, it was painted by a Newar artist probably for Sakya monastery in Central Tibet, sometime during the second quarter of the thirteenth century.[8] An inscription on the back of the painting states that it was consecrated by Sakya Pandita (1182-1251), the charismatic leader of the Sakya order when it was the hub of thirteenth century Tibetan political and religious life.[9] Sakya Pandita was also an unwitting accomplice in the creation of the tsakli under discussion.

Fig. 11In 1244, Sakya Pandita was summoned from Sakya monastery to the camp of Godan Khan near Kokonor, in the Qinghai Lake region. (fig. 11) Godan’s armies had conquered large portions of Central Asia and were threatening Tibet’s borders. His army had already made several punishing raids into Tibet, and Godan was looking for a Tibetan with whom he could negotiate a Tibetan surrender. His advisors recommended Sakya Pandita, the same man chosen for the task by Tibetan leaders themselves.[10] Sakya Pandita took two nephews, the elder was a ten year old later known by the epithet Phakpa, “Exceptional”. They arrived at the Mongol encampment in 1247. Soon after his arrival, Sakya Pandita cured Godan of what was thought to be a fatal illness, thereby winning Godan’s respect and gratitude. The Sakya leader was able to secure relative freedom for Tibet in exchange for political cooperation, the approbation of Tibet’s religious hierarchy, and the promise of generous tribute.

In a letter written to his Tibetan colleagues from the Mongol encampment, Sakya Pandita explained the situation: “The Prince [Godan] has told me that if we Tibetans help the Mongols in matters of religion, they in turn will support us in temporal matters. In this way, we will be able to spread our religion far and wide… If I stay longer, I am certain I can spread the faith of the Buddha beyond Tibet and, thus, help my country. The Prince has allowed me to preach my religion without fear and has offered me all that I need. He tells me that it is in his hands to do good for Tibet, and that it is in mine to do good for him. He has placed his full confidence in me… I have been preaching constantly to his descendants and to his ministers, and now I am getting old and will not live much longer. Have no fear on this account, for I have taught everything that I know to my nephew, Phakpa.” [11]

Phakpa was instrumental in the creation of a Sino-Himalayan school of art at the Yuan court. After Sakya Pandita died in 1251, Khubilai Khan formed an alliance with Phakpa along the lines of that enjoyed by their ancestors Godan and Sakya Pandita, a priest-patron relationship known in Tibet as Yoncho (yon mchod).[12] Phakpa is said to have insisted that Khubilai assume a lower seat when he received religious instruction from him; when discussing political matters, Phakpa and Khubilai were said to have been seated at equivalent levels.[13] We will return to their alliance later in this essay, but suffice it to say that they served each others’ aspirations: Phakpa provided Khubilai with a Buddhist worldview which legitimized and sanctified his rule; and Khubilai endowed Phakpa with tremendous wealth and power by which to spread the Buddhist faith.[14]

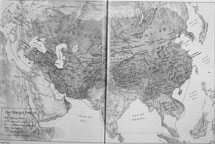

Fig. 12When at the height of his power, Khubilai ruled vast portions of Asia, effectively controlling nearly two-thirds of the known world. (fig. 12) The Mongol Empire encompassed the territories stretching from Korea to western Russia in the north and from Vietnam to Syria in the south. Within half a century, they had overwhelmed the Jin (1115-1234) and Song (960-1279) dynasties in China, as well as huge stretches of Central and Western Asia and North Africa. In 1260, Khubilai declared himself Great Khan. A few months later he appointed Phakpa National Preceptor (guoshi) and asked Phakpa to perform his enthronement ceremony. Phakpa needed artists to create the imagery necessary for the many Tibetan Buddhist rituals that were to become essential activities at the Yuan court. When Khubilai asked Phakpa to arrange a memorial stupa in memory of Sakya Pandita, Phakpa went to Sakya monastery in Central Tibet to gather together the best artists he could find.[15] He also requested artists from the Nepalese king. Eighty (said also to have included Indians) were sent, led by the supremely talented seventeen-year-old Nepalese artist known as Anige (1244-1306).[16]

A painting in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, one of three that survive from an original set of five, was produced for Sakya patrons by a Nepalese artist c. mid-thirteenth century—around the time Anige and his atelier were working at Sakya.[17] (fig. 13) The upper throne in the Los Angeles painting includes two golden makaras (mythic crocodilian figures), one on either side of the arch, their wide-opened jaws spitting gems, and an elegant spray rising from behind their tails. (fig. 14) Within this spray emerges a green snake (naga) that makes one loop on either side before forming a canopy for two deities who flank Garuda (half-man, half-bird), at the summit. One sees much of the same configuration, albeit simplified, in the tsakli paintings under discussion. In the upper throne of the Amitabha tsakli in figure 15, one finds the same makara-naga configuration, and the pattern of the makara’s golden spray is virtually identical with that in the Los Angeles painting, as is the loop of the snake. In this tsakli, the artist renders a similar figure known as chepu (kirtimukha, skt.), in which only the head and hands appear, perhaps a concession to the tsakli’s smaller format.

Fig. 16The structure of the lower throneback in the Los Angeles painting consists of a register of animals. (fig. 13) In the tsakli paintings, one finds a fluted pillar topped by a lotus, surmounted by a short pedestal supporting a makara. (fig. 16L) This rendering of a lower throneback can also be found in thirteenth century Nepalese painting, as illustrated here in a thirteenth century Nepalese painted bookcover, now in the national collections in Kathmandu. It shows a divine figure placed between flouted columns, topped by a lotus and a pedestal supporting a makara, just as one sees in the tsakli. (fig. 16R)

The structure of the thronebase in the Los Angeles painting includes a number of subtle details that also appear in the tsakli. Ratnasambhava is seated at the center of an opened lotus, its narrow border a deep green marked with an undulating line. The lotus is supported by a two-tiered, gem-encrusted golden base. Close examination reveals that the base is meant to exist in three spatial planes: a central projection (known in Sanskrit terminology as a bhadra) flanked by two receding planes. Tiny colored lotus petals denote the three spatial planes: blue lotus petals distinguish the central portion; pink petals mark the adjacent receding plane; and green lotus petals distinguish that which recedes furthest from the viewer. (fig. 17L)

One finds precisely the same configuration in the tsakli, albeit simplified, once again almost certainly a concession to their small size. (fig. 17R) Thus, in the Amitabha tsakli, one finds the deity seated on an opened lotus bordered in a deep green, marked with an undulating line. Beneath the lotus petals is a gold, gem-encrusted two-tiered thronebase with a central projection marked by tiny lotus petals in blue (for the central section) and red for the adjacent, receding plane. Inset gems, seen on the thronebase of the Los Angeles painting, are here suggested by a variety of raised gold semi-circular and rectangular shapes that likewise suggest inset gems.[18] In both paintings, a similar throne cloth falls over the central projection.

Further evidence that the main root of the tsakli style lies in c. mid- thirteenth century Newar-Tibetan painting can be seen in a comparison of a standing attendant in one of the tsaklis with that in a painting of Amitabha Buddha, now in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. (figs. 18L, 18R) This painting is from the same set as the Los Angeles painting, produced for the Sakya order by a Nepalese artist c. mid-thirteenth century. Again, allowing for differences in scale between the two works—the attendant figure in the tsakli is 9 cm high, half the size of the Boston painting attendant—there are remarkable structural similarities. The golden crowns, with five gold leaves inset with coloured gems, rest along the forehead and are secured with fluttering cloth ties. A single gem-encrusted gold bauble surmounts the figures’ tall chignons. A long strand of beads falls to the navel; the bracelets and upper armlets are all quite similar in design and execution. The upper armlets consist of gold ropes highlighted by a gold medallion inset with colored gems. Locks of hair, necklaces and earrings are similarly rendered. The figures’ physiognomy and body type are also very similar, reflecting the Nepalese peoples’ small frames and delicate features. The hands are similarly rendered, their palms covered with red henna to the fingertips (see the tsakli’s main deity in fig. 18L), the fingers held in delicate, rounded gestures. Note the structure of the flower in another of the tsakli paintings, extremely close in design and execution to that held by an attendant in the Boston Amitabha painting. (figs. 19L, 19R)

Fig. 20Like the Boston, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia paintings made by Newar artists for Tibetan patrons, the tsakli are painted in glue distemper on cloth, using primarily ground mineral pigments, which remains the traditional technique of Himalayan painting to this day. In tsakli paintings where there is pigment loss, one sometimes sees Tibetan letters serving as color cues to the artist. The detail in figure 20 shows the Tibetan letter “ja” in the underdrawing. As Sir Robert Bruce-Gardner has observed, such color notations served to remind the artist of all the areas in a painting requiring a particular color. Preparing the right admixture of pigments was a laborious process with idiosyncratic results. Color notation would eliminate the need to re-mix a color later, perhaps an inexact match to the original pigment.[19] All the tsakli are bordered in red pigment with a yellow inner border highlighted by a thin gold line, just as one sees in the Los Angeles, Boston, and Philadelphia paintings. (figs. 21L, 21R)

Fig. 21Thus, the technique, composition, artistic vocabulary, palette and line that one sees in the Los Angeles, Boston and Philadelphia c. mid-thirteenth century paintings produced by Newar artists for Sakya patrons are so close to what one sees in these paintings that one is led to conclude that whoever made the tsakli had fundamental knowledge of c. mid-thirteenth century Newar-Tibetan art. And yet, despite the many parallels between the tsakli and these thirteenth century Newar-Tibetan paintings, there are important differences, and these differences also provide critical evidence as to the date and provenance of these works.

A Second Element of the Tsakli Style: Chinese Garments and Textiles, and Similarities with other Chinese Yuan Period Works of Art

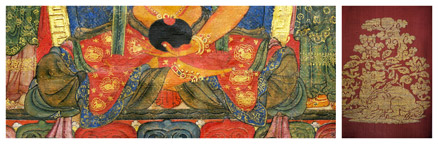

Fig. 22In the c. mid-thirteenth century Nepalese paintings for Sakya patrons cited above, the textiles are Nepalese, as are the garments into which they are fashioned. (figs. 13, 22) Amitabha, the main figure in the Boston painting, wears a tight-fitting lower garment that reveals the shape of the body beneath. He is bare-chested. Standing attendants are also bare-chested, their lower bodies dressed in a patterned, diaphanous Nepalese cloth, further adorned with scarves slung low on the hips, their ends arranged in neat flutters. (fig. 22)

Fig. 23In the tsakli representing Amitayus (essentially the same deity as that in the Boston painting), one sees something very different: the body is cloaked. (fig. 23) A wide green scarf covers the shoulders and upper arms, and the torso is draped in a blue cloth cinched at mid-torso by a white sash. The lower body is covered with layers of (presumably silk) cloth: a blue cloth bearing gold cloud pattern covers the legs, itself layered with a pink garment bearing a green, gold-decorated border. The green shawl twists and turns in space, making nearly symmetric loops on either side of the torso and revealing the underside of the garment in contrasting saffron yellow. The pink cloth falls in deep folds. Most of the fabrics bear delicate designs in gold. Importantly, the cloth depicted in the tsakli as well as the manner in which they are rendered is not Nepalese, but Chinese. Before further examining this visual evidence, let us briefly return to Phakpa and Anige at Sakya monastery in 1261.

Following the successful construction of a memorial for Sakya Pandita at Sakya monastery in Central Tibet, Phakpa insisted that Anige accompany him to the Yuan court.[20] In late 1262, Anige arrived in Dadu (Beijing) and was introduced to Khubilai Khan. Chinese and Tibetan histories report that the Emperor was favourably impressed with the talented, handsome artist and presented him with an artistic challenge.[21] A Southern Song bronze of an intricate Chinese acupuncture model, given to a Mongol envoy in 1232, had been damaged and was judged to be irreparable by the leading court artists. Could Anige repair it? To the immense pleasure of Khubilai and to the astonishment of the court artists, he did so, completing the repairs in 1265. Anige had won Khubilai’s confidence.

In 1269, he became Supervisor-in-chief of the Artisans of the Grand Capital (Dadu renjiang zongguan fu), responsible for overseeing all imperial commissions in painting, sculpture, architecture, and textiles. Anige took orders directly from Empress Chabi and from Khubilai. Thousands of artists—said to include Tibetan, Nepalese, and Chinese--worked under his direction.[22] He trained Chinese artists in the making of Himalayan-style sculpture; he also had the opportunity to learn Chinese painting and sculpture from the many commissions on which he worked with Chinese artists. Anige studied Chinese language, became proficient in the art of Chinese calligraphy, and is said to have collected Chinese paintings. He was lavishly compensated for his work—given vast properties, gold, silver, and silk. He married a Song dynasty princess and his residence was that seized from the Song dynasty heir apparent.[23]

Few examples of the Sino-Himalayan style developed by Anige and his atelier survive. In introducing Chinese art under the Mongols in their ground-breaking book of 1968, Sherman Lee and Wai-kam Ho noted “the far-reaching influence of the Nepalese style” introduced by Anige and his atelier, but they were unable to describe it in detail because so few examples remain.[24] Heather Karmay’s pioneering Early Sino-Tibetan Art (1975) included important artistic and literary references to the Yuan Sino-Himalayan school.[25] More recently, Anning Jing published a wealth of information about Mongol patronage of Tibetan Buddhist art both at the Yuan court and in Tibet proper, drawn mostly from Chinese historical sources.[26] In 2010, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York mounted an important exhibition of Yuan period Chinese art, focusing primarily on Chinese traditional arts. The exhibition catalogue contains a brief but informative essay on the Sino-Himalayan style, including significant examples that have come to light in recent decades.[27]

Within the surviving corpus of Yuan period Sino-Himalayan objects is a woodblock frontispiece to the Chinese Buddhist canon, printed in 1301.[28] (fig. 24) The frontispiece presents the enthroned figures of Shakyamuni Buddha and a Tibetan monk, flanked by four standing attendants. The physiognomy of the figures is essentially Nepalese, and the throne structure (particularly the upper throneback and the thronebase) is essentially that seen in the tsakli, analyzed above.

Also of interest is a gilt copper alloy sculpture of Manjusri, now in the Palace Museum Beijing, dated 1305.[29] Like many figures in the tsakli under discussion, Manjusri wears large hoop earrings decorated with lotus petals, as well as strands of beads, short and long, enhanced with large coloured gems. The crowns are also similar, consisting of a five-leaf diadem, each leaf embedded with a large inset gem. (figs. 25L, 25R) The rock carvings at Felai Feng in Hangzhou, constructed primarily during the Song and Yuan periods, provide further evidence of Yuan period artistic parallels for the tsakli.[30] Figure 26 compares the designs of an inset central gem enclosed by lotus petals, surrounded by additional inset gems. (figs. 26L, 26R)

Fig. 27Stone carvings at the Juyongguan [Cloud Platform] gate, northwest of Beijing, provide other relevant comparisons between the tsakli and Yuan period works of art.[31] Constructed under orders from Emperor Toghun Temur (r. 1333-68), it was planned and overseen by the last State Preceptor at the Yuan court, the Tibetan Kunga Gyaltsen Palzangpo (kun gda’ rgyal mtshan dpal bzang po, 1310-1358) between 1343-45.[32] In many of its iconographic details, the Guardian of the East at Juyongguan resembles a guardian in another of the tsakli paintings under discussion. (figs. 27L, 27R) Both figures play a lute-like instrument, decorated on the body with dragons and clouds. The guardians’ multi-layered costumes and chainmail armour are also similarly rendered.

Figure 28L shows a Yuan silk textile depicting the bodhisattva Manjusri, now in the National Palace Museum, Taiwan. From lotus petals to silk scarves and crowns, the parallels with the Amitayus tsakli are noteworthy. (fig. 28R) In both works, deities’ legs are covered in thick folds of fabric indicated by heavy shading, and the scarfs drape over the lotus petals in a similar manner. An attendant figure in the Amitayus tsakli may be compared with a wooden sculpture of the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara dated 1282, now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York.[33] (figs. 29L, 29R) Note the wooden figure’s lower garment, which resembles that worn by Amitayus’s standing attendants and indeed by most standing attendants in the tsakli. It consists of two layers of cloth, the uppermost significantly shorter than that beneath. There are similarities as well between the physiognomy of the Chinese Yuan wooden bodhisattva and the attendant in the Amitayus tsakli whose face has distinctively Chinese features.

Figure 30 shows a Yuan period wooden sculpture in the Nelson Atkins Gallery. Note the movement and the flourishes in the handling of cloth—the knot in the upper scarf, and the flowing curves along the bottom of the skirt. All find parallels in the Amitayus tsakli in figure 23. Another Yuan wooden sculpture, dating to c. 1300 and now in the Royal Ontario Museum, shows the lower skirt in two layers of fabric and deep folds of fabric along the knees, another characteristic that appears throughout the tsakli paintings. (fig. 31)

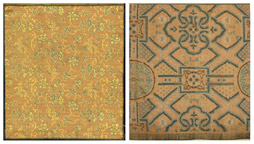

Fig. 32Not only are there clear parallels between the tsakli and Yuan period works with regard to costume design and the handling of fabric, but the textiles depicted in the tsakli are Chinese textiles of the Yuan period or earlier, when identifiable. To cite just a few examples: the meandering pheonix and peony flowers seen here on a pale salmon silk ground is a common motif of the Yuan period. (32L) This textile is used as a mount for the majority of the tsakali. It has been Carbon-14 dated to early Yuan.[34] The geometric-patterned brocade in 32R is structurally consistent with other Yuan period lampas fabrics.

Fig. 33The meandering tendril pattern on the border of many of the fabrics in the tsakli can be found on the border of an inscription at Felai Feng, the Buddhist cave site in Hangzhou, dated c. 1282-92, noted above.[35] (figs. 33 top, 33 bottom) The textile in another tsakli depicts a djeiran or Central Asian antelope, also seen in a textile fragment in the Cleveland Museum of Art, identified by James Watt and Anne Wardwell as of the Jin period (1115-1234).[36] (figs. 34L, 34R) The Cleveland Jin fragment shows the animal against a floral motif with the moon above. Watt and Wardwell note that this antelope also appears in Jin and Yuan art against a cloud, as is seen in the tsakli detail in figure 34.[37] Several of the textiles in the tsakli depict a soaring phoenix in gold; this too appears in surviving Jin period textiles, such as the example on a blue ground, now in the Cleveland Museum of Art.[38](figs. 35L, 35R)

The tsakli paintings are mounted with cloth borders, a customary Tibetan treatment of tsakli meant to be hung during ritual ceremonies. (fig. 36) These fabrics also link the tsakli to the Yuan period.[39] To cite just one example: the detail of one cloth mount depicts birds within cusped medallions against a geometric background. While not identical to the illustration of a fabric drawn from the Yongle Palace, Shanxi, which dates to the early 14th century, it is nevertheless quite close in conception and design.[40] (figs. 37L, 37R) The larger format tsakli have drawings on the reverse of the eight different types of stupas, each referring to different episodes in the life of the historical Buddha. That in figure 38 is the stupa associated with Shakyamuni’s Descent from Tushita Heaven (lha babs mchod rten), identified by a Tibetan inscription.[41]

Other Chinese Elements of Style in the Tsakli

Another important feature in the tsakli painting style, one that differs from its Nepalese antecedents but which does reflect Chinese artistic norms, is a reticence to reveal the human body—in particular, the female body.[42] The detail in figure 39 is from the tsakli depicting Prajnaparamita, Buddhist goddess of wisdom. Also in figure 39 is a detail from a c. mid-thirteenth century painting of Tara, Buddhist goddess of compassion, which was produced for Tibetan patrons.[43] In this great icon of Himalayan art, one finds a consummate expression of Himalayan attitudes to feminine divinity, evident in the sensuality of the bare breasted, compassionate goddess. In contrast, Prajnaparamita’s shoulders and upper arms are covered, and in the portion of the torso that is uncloaked, no breasts are delineated. Other female figures in the tsakli, including a green Goddess, observe similar Chinese norms. (fig. 40)

The same concern to cloak the body has already been observed with respect to the tsakli’s Buddha figures. Amitayus contrasts with the prevailing norms of Himalayan painting as seen in the set of c. mid-thirteenth century Newar paintings produced for Tibetan Sakya patrons. In the Los Angeles and Boston paintings, one sees a naked torso, adorned with jewelry. Not so in the tsakli paintings: shoulders, upper arms, torsos and legs are covered by rich Chinese fabrics. (figs. 41L, 41R) In short, although most features in the tsakli suggest that the artist was well acquainted with c. mid-thirteenth century Nepalese art, one also sees important elements reflecting Yuan Chinese artistic norms.

Evidence in the Shalu Murals

Additional corroborative evidence to suggest that the tsakli were created at the Yuan court ateliers can be found in the murals of Shalu monastery, founded in 1027, and located about 20 kilometres southeast of Shigatse in Central Tibet.[44] Its leaders had close political and familial ties with the Sakya order. In 1306, Shalu prince Drakpa Gyaltsen arrived at the Yuan court to be formally instated as ruler of Shalu and to be given the title Imperial Advisor (Gu-shri) by Kubilai Khan’s successor Timor (1265-1307).[45] While at court, Drakpa Gyaltsen secured the services of artists trained by Anige (who had died in 1306) to carry out important renovations that he planned for Shalu.[46] Murals completed by the Yuan court artists at Shalu between 1306 and 1333 are still in situ.

Fig. 42Among Drakpa Gyaltsen’s renovations was the creation of a library in the south chapel. An image of Shakyamuni Buddha in the Kanjur Lhakhang (’bka ’gyur lha khang) at Shalu exhibits many similarities with the Amitabha tsakli, particularly in the face, head and ushnisha (cranial protuberance) of the main figure. The upper throne back, throne base, and the folds of fabric along the left shoulder and lower legs are also similarly rendered. (figs. 42L, 42R)

That the tsakli paintings and the early 14th century murals at Shalu are closely related is evident also in minor details, such as the pattern of inset gems on thrones. In the tsakli thrones, one sees an alternating sequence of rectangle and semicircle in raised gold. This pattern, meant to suggest the shapes of gems set into gold, is virtually identical to that on the gold upper throne bar above Amitabha’s shoulder in the Shalu mural. (figs. 43T, 43B) A comparison of the faces and jewelry of other divinities in the 1306-33 murals of Shalu and in the tsakli also reveal close parallels. Note the lips, noses, eyes and eyebrows, as well as the lotus-petal hooped earrings in figures 44, 45.

As was stated above: the technique, the composition, the artistic vocabulary, the palette and the line that one sees in the tsakli are so close to what one sees in the c. mid-thirteenth century Los Angeles and Boston paintings (produced by Newar artists for Sakya patrons) that one is led to conclude that whoever made the tsakli was very familiar with this phase of Tibeto-Newar art. It is instructive to compare the Boston Amitabha with an Amitabha in the Shalu murals produced by Yuan court artists. (fig. 46) Striking parallels can be found in the crown design, necklaces, upper armlets, anklets, lotus petals and throne design, lending further support to the notion that the Shalu murals were produced by artists trained in the same Tibeto-Newar tradition, created fifty to one hundred years later than the Boston and Los Angeles paintings.

As noted above, one of the distinguishing features of the tsakli style is its Chinese costumes and textile designs. A comparison of the same Amitabha at Shalu with the iconographically comparable Amitayus in the tsakli is further instructive. (fig. 47) The tsakli figure is cloaked in layers of rich Chinese fabrics. In the Shalu murals produced by Yuan court artists, Nepalese textiles and costumes predominate, most likely reflecting the taste and social norms of the Tibetan patrons. Although the fabric and costume of the Shalu Amitabha is Nepalese, one finds fabric embellishments elsewhere in the Shalu Yuan murals that resemble those in the tsakli. Offering goddesses in long skirts are adorned in scarves that twist and turn, revealing a contrasting color underside, as they do in the tsakli paintings. (figs. 48, 49) This distinctive manner of handling fabric is not seen in Himalayan painting before it is introduced by Yuan court artists in the murals of Shalu, and possibly through other contacts between Tibet and Chinese Yuan artists.[47]

An important question is whether the tsakli were created before or after the c. 1306-33 murals at Shalu. The author’s view is that the tsakli paintings precede the early fourteenth century Shalu murals, although this question would benefit from further research and will be briefly revisited below. The Shalu murals show the kind of flourishes that one sees when a style is in its later stages. The shape of the golden spray from which the sea monster emerges is more ornate than that in the tsakli, its pattern more precise, the effect more decorative. (fig. 50) Likewise, the scrollwork in the Shalu throne cushion is more emphatic than that in the tsakli paintings and in the c. mid-thirteenth century Los Angeles and Boston paintings; and in the Shalu painting, the snake’s loop has become a circle against a red background that provides additional contrast in the design. (fig. 51)

Iconographic Evidence for a Yuan period attribution

Fig. 52Important iconographic evidence in the tsakli suggests they are not only of the Yuan period but perhaps may be specifically associated with the court of Khubilai Khan, who died in 1294. The Buddha paintings in the first circle of the tsakli mandala include a spiritual lineage illustrating Sakya teachers (recognizable by their distinctive red peaked caps) and their Indian Buddhist predecessors.[48] (fig. 52) Although none of the figures in this spiritual lineage can be identified with certainty, it is possible to postulate the identities of two other historical figures, each the subject of a tsakli painting.

One is a youthful-looking Sakya monk in the teaching gesture, flanked by Sakya monks richly attired in robes adorned with patterns of gold. (fig. 53) This is the only Sakya monk whose portrait is the subject of a tsakli painting and, in this respect, he is given equal status to the historical figure represented in figure 54. The male figure in this painting wears boots and a red under robe adorned with a golden wheel (chakra), cinched at the waist with a gold sash. A gold-adorned short-sleeved blue outer robe covers the shoulders and falls the length of the body. This garb closely resembles that worn by two Mongol rulers depicted as donors in a Yuan period Yamantaka mandala kosu, now in the Metropolitan Museum.[49] (fig. 55) The two male donors are identified by inscriptions as Togh Timor, the great-great grandson of Khubilai, who ruled China as Emperor Wenzong from 1328 to 1332, and his elder brother Khoshila, who reigned briefly in 1329 as Emperor Mingzong. Khoshila on the right in figure 55 wears a costume similar in design to that of the historical figure in the tsakli. It too consists of a red under robe with a short-sleeved blue outer robe that covers the shoulders and falls the full length of the body.[50]

Thus, it is reasonable to infer that the subject of the portrait in figure 54 is a Mongol ruler. Other iconographic elements in the painting shed further light on his identity. He holds the stems of two lotuses bearing a sword and a book, the characteristic attributes of Manjusri, indicating the artist intended to associate this Mongol ruler with the Buddhist deity of wisdom. This iconographic innovation is in keeping with Tibetan artistic norms. For centuries, Tibetan artists had been adapting traditional Indian Buddhist iconography, presenting their own revered political and religious leaders in the guise of Buddhist divinities.[51] In this instance, the artist is likely to have had one historical figure in mind: Khubilai Khan.[52]

Historians agree that Khubilai Khan was known as an incarnation of the bodhisattva Manjusri; the only other Mongol ruler accorded this honor was Altan Khan (1507-82), the protagonist in the Second Conversion of Mongolia to Buddhism.[53] Khubilai Khan’s virtues are extolled in an inscription composed by the last Yuan ruler Togh Timor (Kubilai Khan’s great-great grandson noted above) on Juyongguan gate, just north of the Yuan capital Beijing.[54] The inscription describes the virtues of Buddhism and its champion Khubilai Khan who, it is said, fulfilled a prophecy that Manjusri would incarnate in the vicinity of Mount Wu-tai in China, that he would become a great emperor and a patron of the arts, and that he would live to a great age.[55]

There is some debate as to whether Khubilai was known in his lifetime as an incarnation of Manjusri, or whether this accolade was merely a later attribution.[56] Karl Debreczeny notes, however, that at least two roughly contemporary (13th-14th c.) Tibetan sources discuss Khubilai as an incarnation of Manjusri. In the biography of Urgyanpa Rinchen Pel (1229/1230-1309) written by his student Sonam Ozer (b. thirteenth c.), Urgyanpa remarks that Khubilai was known as an incarnation of Manjusri, and he questions the veracity of this claim. The second source is a slightly later 14th century biography of Monlam Dorje (1284-1346/7) by his son Tselpa, in which Khubilai is described as a “wondrous manifestation of Manjusri.”[57]

The artist ascribed yet another accolade to Khubilai Khan in this portrait. The Mongol ruler wears a red cloth turban surmounted by the head of Amitabha Buddha. This feature—a cloth turban surmounted by the head of Amitabha—appears in only one other context in Tibetan art, when it signifies Songtsen Gampo (d. c. 649), first historical ruler of Tibet, a great champion of Buddhism and its arts and perhaps the most celebrated political figure in Tibetan history. Songtsen Gampo is represented in a sculpture in the Potala in Lhasa, wearing a cloth turban surmounted by the head of Amitabha.[58] (fig. 56) This iconographic feature was associated with Songtsen Gampo at least since the twelfth century, when it appears in a painted portrait of the king, now in a private collection.[59] This unique iconographic composite, in which Khubilai Khan appears as the incarnation of Manjusri while also bearing the attributes of Tibet’s greatest religious king, suggests the high esteem in which the great Khan was held by the patron(s) of the tsakli.[60]

It is interesting to note that according to the official Sakya history of this period, Phakpa and Khubilai discussed Songtsen Gampo during their first meeting in 1253 or 1254.[61] Khubilai was warming to Phakpa whose “well reasoned responses” were a refreshing change from the inept Tibetan lamas he had seen previously. Phakpa’s intelligence, his strength of character, his learning, and his fine diplomatic skills are apparent in the dialogue attributed to them in this official history. When asked by Khubilai Khan to name the great Tibetan political figures of the past, Phakpa cites Songtsen Gampo and two of his successors, all great champions of Buddhism. When asked why Songtsen Gampo was so great, Phakpa responded that he was an incarnation of Avalokitesvara. Soon thereafter, Phakpa informs Khubilai that Songtsen Gampo had also conquered China, and had subsequently taken control of two-thirds of the known world.[62] The parallels with Khubilai Khan are clear. As was noted above, Phakpa and Khubilai Khan served each others’ aspirations: Phakpa provided Khubilai with a Buddhist worldview which legitimized and sanctified his rule; and Khubilai provided Phakpa with tremendous wealth and power by which to spread the Buddhist faith.[63]

The presence of significant Yuan Chinese stylistic features in the tsakli, noted above, make a Chinese provenance more likely than that of Tibet proper. Bhaisajyaguru mandala rituals, for which the tsakli were made, may well have been conducted by Phakpa and others within the sizable community of Tibetan monks integral to Yuan court life. In Khubilai Khan’s later years, between twenty-eight and seventy-two Tibetan Buddhist rituals were held annually. By 1330, three hundred and sixty-seven Buddhist temples received regular subsidy from the government; the top twelve Imperial Buddhist temples had a combined 3,150 “official monks” responsible for rituals and performances at the court.[64] According to Anning Jing, “…elaborate Tibetan Buddhist rituals were performed regularly at Dadu (the Great Capital), and Buddhist symbols of universal rule, such as the wheel (cakra) and the white parasol, were displayed prominently at court. The imperial procession was guided by an iron cakra [wheel] made by Anige.[65]

The Yuan court was the epicentre of Yuan power, where Khubilai Khan and Phakpa lived and where Anige’s atelier was based. Because of the enormous patronage afforded Tibetan Buddhism and its art, in some years amounting to nearly half of the national budget, Jing has described the Yuan capital Dadu [Beijing] as “the greatest center of Tibetan Buddhist art” in its day.[66] In 1275, Anige was in charge of at least 3000 “artisan households;” a few years later, he commanded at least another ten thousand artisan families.[67] Jing states that among the professional court artists in Anige’s atelier in the capital, known as the Supervisorate of All Classes of Artisans, roughly half were Nepalese and Tibetan, and half were Chinese.[68]

It is significant that when Yuan court artists worked in Tibet at Shalu, they depicted Himalayan textile and costume design. The presence of Khubilai Khan in the tsakli, and presumably Phakpa in figure 53, also point to a Yuan court attribution. Of their complimentary roles, Phakpa wrote: “Secular and spiritual liberation are something that all human beings try to achieve. Both depend on a dual order—the order of religion and the order of the state. The order of religion is presided over by the Lama; and the state by the King. The heads of religion and the state are equal, though with different functions.” Further articulating this worldview, Herbert Franke wrote “The Lama corresponds to the Buddha, and the Ruler to the cakravartin. In each era of history these highest dignitaries appear only once. In the thirteenth-century they were P[h]ags-pa and Khubilai.”[69] Anning Jing confirms, “the Imperial Preceptor was the most prestigious figure under the Emperor.”[70]

In 1276, upon what would be his final departure for Tibet, Phakpa was given the title Dabao fawang, “Great Precious King of the Dharma,” a title of supreme religious authority.[71] Four years later, he died aged 45 in Central Tibet, allegedly poisoned by a political rival.[72] The Yuan title Imperial Preceptor was subsequently assumed by thirteen successive Tibetan monks between 1276 and 1368.[73]

Fig. 57While a Yuan-period attribution for the tsakli can be confidently argued, it is less certain whether a more precise chronological attribution can be made. Were the tsakli commissioned during the reign of Khubilai Khan and produced in the extensive atelier of Anige? In this author’s opinion, this is a very likely possibility. The tsakli appear to be earlier than the c. 1306-33 murals at Shalu created by Yuan court artists.

The tsakli also appear to be earlier than the Metropolitan Museum’s Yuan Yamantaka kossu (dated 1330-32). The Sakya hierarch in the tsakli and the lineage of Buddhist masters in the kosu reveal very different handling of robes, halos and ornamental scrolls (fig. 57) The kosu’s light green flowering tendril of variegated blossoms compares closely with that in the Buddha’s halo at the Juyongguan Gate, dated by inscriptional evidence to 1343-45. (fig. 58) The Juyongguan Gate Buddhas are more Sinified in facial features and body type, quite different from the Himalayan physiognomy in the tsakli. (fig. 59) Their thrones differ significantly, and the Buddha images at Juyonguan Gate can be said to foreshadow Yongle period sculpture (1403-24), with which they share many elements of style.[74] (fig. 60) Finally, a comparison of the figure of Dhritarashtra in the tsakli with that in the c. 1427-1442 murals at the Gyantse Kumbum reveal continuities in iconography and style (e.g., the musical instrument, and the rendering of the hand, helmet and some textiles). (figs. 61L, 61R) The Gyantse murals, however, present these elements within a different stylistic grammar, the mature expression of an indigenous Tibetan style well over a century after the tsakli were made.[75]

Fig. 61“With the collapse of the [deeply unpopular] Mongol regime, most Tibetan monuments in China fell victim to anti-Mongol sentiment.”[76] Only a small fraction of the Sino-Himalayan art works produced at the Yuan court survive. The author has argued that these tsakli are among them, as difficult as this is to establish given the paucity of the artistic record. Nevertheless, there is sufficient visual and literary evidence to make a strong case that these beautiful paintings were created under Yuan imperial patronage, by an international atelier trained by the Nepalese artist Anige.