A

Rarity in Chinese Contemporary Art

by William Hanbury-Tenison

September 10, 2007

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

Rarely, if ever, does the auction market afford a comprehensive snapshot of another time and another place. Yet, on the 20th September 2007 at 2pm, Sotheby’s New York will be offering 12 paintings from the 1980s in China at the auction Contemporary Art Asia. The paintings, lots 107 to 118, may be viewed at Contemporary Art Asia: China, Korea, Japan.

The 1980s in China were a time of intellectual ferment and political experimentation, when Deng Xiaoping and his colleagues tried to push a reform agenda in the face of strong and hard line communist resistance organized by Chen Yun, Deng Liqun and others. The decade also saw a great outburst of excitement among the younger generation of artists, whose creativity had been stifled by 20 years of left-wing socialist realist orthodoxy culminating in the 10 years of Cultural Revolution (1966-76). The 1980s saw this generation of artists exposed to every kind of cultural influence from ancient Chinese to post-modernism. Their works of that decade were a response to the wild ferment of the times and thus were conformist only to the extent that they differed from each other and attempted to differ from the immediate past.

At that time the market for contemporary Chinese art was extremely thin. The Chinese diaspora was much more interested in collecting the work of the established masters of Chinese ink painting such as Zhang Daqian and Pan Tianshou. To them the work of the younger generation seemed too foreign in influence. Among the small numbers of foreigners who lived in and visited Chinese at that time, there were those (such as “Joan” 1985, lot 110 by Zhao Weiliang) who spent time with the younger generation of artists and also those who wrote and published, as did Joan Lebold Cohen with “The New Chinese Painting” of 1987.

This situation changed dramatically with the events of June 1989. In response to the death and official ignominy of deposed Party Secretary Hu Yaobang, student demonstrations broke out. The government was divided over how to control the situation, which quickly got way out of hand with tens of thousands of students camped in Tiananmen Square and millions participating in peaceful demonstrations around the country. Finally the then Party Secretary Zhao Ziyang was deposed and replaced by hardliners who ordered martial law and the clearing of the square with tanks and troops using live rounds.

In the chaos and bloodshed that ensued a large number of young artists left China and were granted asylum in foreign countries such as the USA (Wang Gongyi (lot 116), Zhao Weiliang (lot 110) and Wei Luan (lot 107)) and France (Chen Jianghong (lot 108)). Others stayed in China and kept their heads low in art schools or joined artists’ colonies at the Yuanmingyuan in Beijing or in Shenzhen near the border with Hong Kong. In the years that followed a much more sophisticated and commercial art began to come out of China, professional dealers and collectors became more widely involved and the spirit of innovation that pervaded the 1980s was replaced by something much more market-driven.

In the United States, two seminal exhibitions caught the mood of the 1980s in China and brought Chinese contemporary art to the attention of the American public for the first time. The first, “’Beyond the Open Door’ Contemporary Paintings from the People’s Republic of China” was curated by Waldemar A. Nielsen and Dr. Richard E. Strassberg and held at Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena under director David Kamansky in 1987. The catalogue includes a foreword by Henry Kissinger, indicating the level of interest in this pioneering exhibition at the time. The second exhibition, “’I Don’t Want to Play Cards with Cezanne’ and Other Works Selections from the Chinese “New Wave” and “Avant Garde” Art of the Eighties” with paintings selected by David Kamansky, Richard Strassberg and Tang Qingnian was also held at Pacific Asia Museum in 1991.

The first exhibition featured 46 works and the second 41 works, most of which were purchased by collectors after the closing of the exhibitions. At that time it was not possible to mount a loan exhibition with works from China and the organizers had had to purchase all the works and were only able to recoup their expenses by selling the works on (for only very modest gain).

A survey of the 87 works exhibited at Pacific Asia Museum reveals the extraordinary prescience of the group that selected them. Several of the artists now considered major in the field of Contemporary Chinese Art such as Zhang Xiaogang, Xu Bing, Ye Yongqing (lot 118), Yu Xiaofu, He Duoling were all included. So also are the works of many artists whose works are considered important in China but have not yet been seen at auction in the United States: these include Geng Jianyi, Chen Jialing (lot 117), Huang Fabang (lot 115), Zeng Xiaofeng (lot 114) and Chen Ren (lot 113) among others.

What is even more interesting, however, is the presence of works by a number of artists whose life experience since Tiananmen has led them far away from the influences that guided their work in the 1980s. These include Xin Haizhou (lot 111) and Shen Xiatong (lot 112), whose present works reveal a depth of emotion that is not so evident in their more commercial work of recent years.

Some among the collection at present are among the greatest masterpieces ever made by these artists and have a historical and art-historical significance that goes beyond their status as “early works”.

The two exhibitions, for example, contained two works from Huang Fabang’s “National Martyrs Series”. The first, exhibited in 1987, is a stunning ideal portrait of Huang’s teacher at the Hangzhou Art Academy, the eminent painter Pan Tianshou, who was hounded to death during the Cultural Revolution. The second (lot 115) shows the recumbent body of China’s President Liu Shaoqi who was also persecuted to death during the Cultural Revolution. The very title of this series is deeply cynical, appropriating the revolutionary title of ‘Martyr’ to those stripped of their political rights and tortured to death by the leftists within the Chinese Communist Party.

Chen Jianghong’s “Temptation’ (lot 108) is a caustic comment on the behaviour of China’s Liberation Army after the launch of Deng Xiaoping’s reform policy. Casting their revolutionary credentials as the ‘People’s Army’ to one side, the army’s leaders and their children quickly succumbed to the temptations of Deng’s exhortation that ‘some must get rich first’.

Zeng Xiaofeng’s monumental and magnificent triptich “Night” (lot 114) reflects deeply on the hidebound nature of Chinese society in the 1980s, when social liberalization was offset by frequent campaigns again “bourgeois liberalism”, launched with great savagery against the artistic classes if their works happened to offend one of the senior leaders or their creatures in the Ministry of Culture.

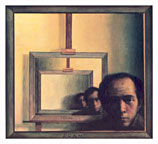

More personal reflections on the state of Chinese society in the 1980s are to be found in Du Jiansen’s searching “Frame of Mind” (lot 109), Ye Yongqing’s “Lost in Thought” (lot 118) and Xin Haizhou’s “Bald-Headed Youth” (lot 112). In these works the artists look inward, use the forms of western art and the art of psychoanalysis to probe their own nature at a time of shocking change and social upheaval.

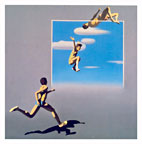

Finally Chen Ren’s “Jump for Joy” (lot 113), which was widely disseminated at the time, is a wry comment on the path of Chinese youth. A young man is depicted running into a future that sees him jump over but not through a frame that contains a promising blue sky. From the perspective of today’s polluted and industrially blighted Chinese with its disillusioned population facing huge financial challenges engendered by profiteering and inflation, the feigned innocence and the foresight of Chen Ren’s painting are truly astounding. This sense of China in the 1980s at the cusp of a lost innocence is also to be seen in Shen Xiaotong’s “Paradise Lost” (lot 111) where a group of Chinese artists surround an ethereal table attending a ghostly Last Supper.

The 12 paintings from “Open Door” and “Cezanne” have never been seen on the market. The collector has decided to release this group from his substantial holdings in order to give a new generation of collectors as well as museums a chance to add depth to their holdings of Chinese Contemporary Art by adding works from that seminal period, the 1980s.

© William Hanbury-Tenison

Fine Art Agent

August 29, 2007