asianart.com

HOME | TABLE OF CONTENTS | INTRODUCTION

Download the PDF version of this article

by Eva Seegers

(Numata Center for Buddhist Studies, Asia Africa Institute, University of Hamburg/Germany)

Published May 2020

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

This essay discusses the stūpa, or caitya (Tib. mchod rten)[3], in the historical area of Khams of the Sino-Tibetan borderland. It surveys for the first time and provides stylistic analyses of selected stūpas built after 1959 as part of the massive rebuilding of material culture and Buddhist revival of Eastern Tibet. The survey is based on a combined religious and art-historian approach by focusing on the description, classification and interpretation of sites and stūpas.

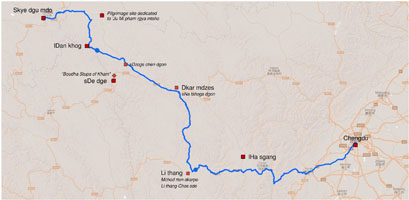

Map 1 The stūpas examined here are located in a long stretch of land spanning the far eastern (Chengdu) and the northwestern (Jyekundo; sKye dgu mdo) regions of Khams (Map 1). They dot the Lhagang (lHa sgang) grasslands, the banks of the Yalong River (Dza Chu) and the basins of the Upper Yangtze River (Dri Chu). Since ancient times, trade routes crisscrossed this area connecting Southwest China with Central Tibet. During the time of the Tibetan Empire and the Chinese Tang dynasty (618‒907) onwards trade and transcultural exchange flourished and for many centuries Jyekundo was an important Tibetan trade hub on a branch of the Silk Road.

Today, this broad area belongs to “ethnographic Tibet”, which refers to the ethnic Tibetan area of Khams that forms part of China’s Qinghai and Sichuan provinces.[4] Most of the stūpas discussed here are positioned within the Kandze (Dkar mdzes) Prefecture in western Sichuan, and in the Yushu Prefecture of Qinghai. Recent studies of the Sino-Tibetan borderlands have examined such topics as the reestablishment of religious and ritual life, local histories of Khams, and old and new monasteries and sacred sites in the area, for example.[5] Research into questions concerning continuity, adaptation, and the loss of Buddhist stūpas in Khams is still in its infancy, however. Andreas Gruschke’s pioneering survey of monasteries and sacred sites includes some stūpas but is not comprehensive. Reports by the Tibet Heritage Fund on the renovation of some old stūpas, like the lHab Phan ’dun stūpa in Chamdo (Chab mdo) county, and my own comparative study on two monumental stūpas in Yushu county– are humble additions to this topic.[6]

This essay seeks to contribute to the overall picture of the stūpas of Khams, addressing the following topics: the main stūpa types observed in Khams; stūpas and (the revitalization of) ancient pilgrimage sites dedicated to “princess” Wencheng Gongzhu and other prominent figures in Tibetan history and the creation of new sacred spaces. The inquiries into this vast topic discussed in this essay, are twofold: where and why have the stūpas been erected, and what is their architecture and décor?

China’s attack on Tibet in 1950 marked the onset of the upheaval of Tibetan culture and religion. Mao Zedong’s People’s Liberation Army occupied all of Tibet in 1959 and replaced the Tibetan government with a Chinese dictatorship. During the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966–1978), all religious practices were banned, lamas and monks were defrocked, and most material culture that was religious in nature, such as temples (exterior and interior) and stūpas, was demolished.[7]

When traveling through Khams today, however, a striking number of stūpas catch the eye (approximate estimate: two thousand—if you count the stūpas on the wall of a monastery one by one). This stūpa-building boom started after Mao Zedong passed away in 1976. His successor Deng Xiaoping moved away from the Chinese Communist Party’s strict anti-religious policy and reverted to a more pragmatic viewpoint that was dominant in the 1950s. The historic Third Plenum of the Eleventh Chinese Communist Party Congress, held in Beijing in December 1978, ushered in a series of wide-ranging reforms. One reform led to the renovation and rebuilding of monasteries and stūpas as of 1980. Natural disasters such as the 2010 earthquake in Yushu county which greatly damaged vernacular and religious architecture also stimulated public funds for reconstruction work. In short, most stūpas standing today were built during the last three decades—and the building boom is ongoing.

Preliminary Remarks on Stūpas

Stūpas, a key visual representation of Buddhism, are part of the characteristic material culture of Tibet at least since the phyi dar, the second diffusion of Buddhism (10./11th centuries). Countless scholarly studies have plumbed their meaning and function.[8] To summarize, stūpas evolved from Indian origins, as simple dome-shaped mounds enshrining the relics of the Buddha, over more than two thousand years. From these ancient reliquaries, stūpas have developed into very complex structures with deep, multilayered symbolism. Traditional Tibetan sources explain the stūpa in the context of the concept of sku gsung thugs rten, the receptacles of the body, speech, and mind [of Buddha]. Among these three, the stūpa is the visual representation of the mind of the Buddha (thugs rten). For Buddhists, the stūpa is a common tool by which to accumulate merit and in so doing improve karma. Indian sources like the Adbhutadharmaparyāya explicate the great merits accrued by constructing and venerating a stūpa, even those the size of the tiny myrobalan fruit with a central axis as small as a needle.[9] When Tibetans translated the Sanskrit terms caitya or stūpa, they formulated it according to its principal meaning: mchod rten (lit. receptacle or object of worship). Certain key principles are necessary to transform a stūpa into a receptacle of worship, and a skilled tantric teacher (Tib. rdo rje slob dpon, Sk. vajrācārya) is responsible for their effective implementation. These include geomantic instructions for the examination and preparation of the ground, and the exact timing of all steps in the building process,[10] the measurements of the stūpa, and the content of the treasure chambers inside.[11] The rdo rje slob dpon brings knowledge of the exact method for arranging the relics, maṇḍalas, and the central axis, or life-tree (srog shing), inside the stūpa; he is also responsible for rituals and consecrations before and during the actual construction. When the stūpa is completed, the rdo rje slob dpon performs the critical final consecration ritual (Tib. rab gnas; Sk. pratiṣṭā) whereby stūpas (or) images are transformed into sacred objects.

Speaking of the stūpas in Khams, we may assume that the involvement of a skilled rdo rje slob dpon signifies that the stūpa project will almost certainly follow Tibetan religious tradition. Evaluating whether the mass of new stūpas in Khams were supervised by such experts is not within the frame of this paper, however, as it must be determined on a case-by-case basis. We did observe this to be true in the case of two ancient monumental stūpas in Zhom ’gyu at the west bank of the Upper Yangtze River (Dri Chu), approximately fifty kilometers south of Jyekundo.

-

1. Stūpa Types Observed in Khams

Fig. 1a |

Fig. 1b |

Fig. 2a |

Fig. 2b |

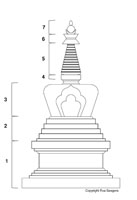

The architecture of each of these caitya types is roughly divided in the following manner as shown in Figure 3:

(1) the throne (gdan khri), which is often decorated with a pair of snow-lions; (2) a section with tapered tiers designed differently for each type; (3) the vase (bum pa); (4) a square component on top of the vase (bre, more commonly known as the Sanskrit harmikā); (5) thirteen wheels (’khor lo) topped with (6) a rain cover (char khebs) or parasol (gdugs), (7) a moon (zlaba), a sun (nyi ma), and a jewel peak (nor bu’i tog).[16]

Fig. 3 |

Fig. 4 |

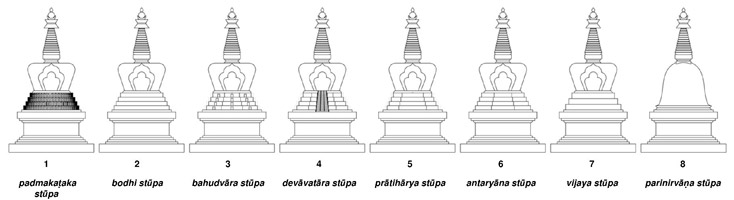

- pad spungs mchod rten (Sk. padmakaṭaka stūpa)—the lotus heap stūpa commemorating Buddha’s birth in Lumbinī; five or seven tapered round tiers, decorated with lotus petals.

- byang chub mchod rten (bodhi stūpa)—the enlightenment stūpa referring to Buddha’s enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree in Bodh Gayā; four square tapered tiers.

- bkra shis sgo mang mchod rten (bahudvāra stūpa)—the auspicious many-gated stūpa symbolizing the turning of the wheel of dharma in the Deer Park of Sārnāth; four square tapered tiers formed with a small ledge with niches which are sometimes equipped with images.

- lha babs mchod rten (devāvatāra stūpa)—the descent from heaven stūpa commemorating Buddha’s descent from the heaven of the thirty-three gods (Sk. trāyastriṃśa deva) in Sāmkāśya; four square tapered tiers formed with a small ledge and three ladders on each side.

- chos ’phrul mchod rten (prātihārya stūpa)—the great miracle stūpa referring to Buddha’s performing of great miracles in the Jetavana Grove Śrāvastī; four square tapered tiers formed with a small ledge.

- dbyen sdum mchod rten (antaryāna stūpa)—the reuniting the sangha stūpa is dedicated to the unification of the divided sangha in Rājagṛha by Śāriputra and Maudgalyāyana; four octagonal tapered tiers.

- rnam rgyal mchod rten (vijaya stūpa)—the perfect victory stūpa commemorating the Buddha’s prolongation of his life-span for three months in Vaiśālī; three circular tapered tiers.

- myang ’das mchod rten (parinirvāṇa stūpa)—commemorating Buddha’s passing away and entering the parinirvāṇa at Kuśinagara; bell-shaped body.

In Khams, entire groups of Eight Caityas appear in a fixed spatial context, either in a row or in two rows of four, forming a solid block. They are organized in one group or together with one additional larger byang chub mchod rten, which is the type most frequently built.

One remarkable example of a reconstructed series of Eight Caityas can be found in Lithang, Kandze Prefecture, on a perimeter wall encircling the monastery Lithang Chöde (Li thang Chos sde). (Figure 5) Also known as Chökhor Ling (Chos’khor gling) it was founded in 1580 by the Third Dalai Lama bSod nams rgya mtsho (1543–1588) as he travelled from Mongolia to Tibet. Lithang Chöde became one of the most influential dGe lugps pa monasteries in Khams.[18] It was bombed and partially destroyed in 1959, then rebuilt in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution. The monastery is encircled with a gigantic perimeter wall that is crowned with many sets of Eight Caityas. This tradition goes back to the first Tibetan monastery Samye (bSam yas dgon pa) in Central Tibet, which is encircled by a similar wall. All stūpas of Lithang Chöde were destroyed and reconstructed together with the monastery; the re-consecration was performed in 1996.

Fig. 5 |

Fig. 6 |

Fig. 7 |

Fig. 8a |

Fig. 8b |

Fig. 8c |

Fig. 9a |

Fig. 9b |

Fig. 9c |

Fig. 10 |

Fig. 11

Some stūpas are richly decorated in “contemporary Nepalese style“, as discussed later.

Prayer wheels (Tib. ma ṇi ’khor lo)[20] are often added to stūpas, either integrated in the stūpa’s architecture or as individual buildings. Some stūpas are erected on a pedestal with 108 prayer wheels as shown in Figure10 or a row of Eight Caityas might share a pedestal that is equipped with prayer wheels, which can be turned by hand when circumambulating the stūpas. Individual blocks of series of 108 small prayer wheels sometimes stand freely near stūpas as well. Particularly striking are some quite large, new stūpa ensembles, which are located in Kandze Prefecture (see Figure 11). Another example of such new creations will be discussed later.

-

2. Observations of Stūpas and (the Revitalization of) Ancient Pilgrimage Sites Dedicated to “Princess” Wencheng Gongzhu and Other Prominent Figures in Tibetan History

We witnessed old and new stūpas and in some cases they even became pilgrimage sites themselves. For example Figure 12 shows three ancient stūpas enshrining the layman clothes of the first Karma pa Dus gsum mkhyen pa (1110–1193), the founder of the Karma bKa’ brgyud tradition. The stūpas are located at Dka’ brag, where he is said to have left his clothes after receiving his novice ordination. According to local oral tradition, the central stūpa enshrines his garments; the left stūpa his left boot, and the right stūpa his right boot.[22]

Fig. 12 |

Fig. 13a |

Fig. 13b |

Certain stūpas in this region reflect religious dynamics that resulted from acculturation processes throughout history—they mark or accompany ancient sites which became pilgrimage sites dedicated to “princess” Wencheng Gongzhu (Tib. rgya bza’ kong jo; d. 680). Local legends state that Wencheng Gongzhu, when travelling from China to Tibet in order to marry Emperor Srong btsan sgam po (r. 617–650) in 641, rested at many sites across Khams. There are two possible routes she would have taken. Sites on the northern route, which is interpreted as her official historical path, are promoted today and have become tourist destinations. Sites dedicated to Wencheng’s southern route are regarded as later examples of pious fiction. Which sites she really visited and which artistic cultural artifacts she really initiated or produced are matters of legend and myth that are shaped according to the narrator. Chinese historians, both ancient and modern, emphasize Wencheng’s Han ethnicity and her role as an ambassadress for Chinese culture who brought many innovations to “backwards” Tibet. For Tibetans, Wencheng is venerated because she is perceived as a physical emanation of Sitatārā (sgrol dkar). She is believed to having brought Buddhism to Tibet, together with Srong btsan sgam po’s Nepalese wife Bal bza’ khri btsun, the emanation of Śyāmatārā (sgrol ma). Scholars commonly agree that too many sites claim to be historical sites of Wencheng today, as it would have taken her much too long to visit all of them.

Map 2Historical records note that she was the niece of Tang emperor Taizong (599‒649) and was sent to Lhasa to marry Srong btsan sgam po in 641. Wencheng Gongzhu is one of two Chinese women who were sent to marry Tibetan emperors as a means of pacifying warring rulers. Peace marriage was a common habit at that time, in fact. As Amy Heller notes, many activities attributed to Wencheng may in fact be those of the Chinese princess Kimcheng, who arrived in Tibet ca. 710. Samten G. Karmay even speculates that the present association of many ancient sites with Wencheng derives in large part from a propagandistic pilgrimage guide written by the Sa skya monk Sangs rgyas rGya mtsho for the purposes of heralding ethnic unity between China and Tibet.[23]

Most of the stūpas outlined in Map 2 are erected at sites that demonstrate how places accrete sacred history. It is beyond the scope of this paper to analyze all sites—there are simply too many—but in the following I introduce several. They lay along the so-called Southern Route and, except for the Vairocana/Wencheng Gongzhu Temple close to Jyekundo, are not officially declared as sites dedicated to Wencheng.

According to local tradition, Wencheng Gongzhu erected the dGe rtse mChod rten mentioned above (see Figure 1) as she journeyed from Xian to Lhasa. Wencheng stopped to cook a meal here and, sensing the spiritual power of the site, she subsequently magically built the stūpa in one night with the help of nāgas (klu; serpent spirit). The legend claims that the ancient remains of the cooking place are still inside the stūpa, below a rock. Since then, the site has been revered as an important pilgrimage site. When the head lama of the Karma bKaʼ brgyud Lineage, the Third Karma pa Rang byung rdo rje (1284‒1339), visited the area, he was apparently very moved by the dGe rtse mChod rten and so founded the nearby monastery Zhom ʼgu dgon.[24]

Fig. 14a |

Fig. 14b |

Fig. 15a |

Fig. 15b |

Fig. 15c |

Two ancient rock carvings dedicated to Wencheng can also be found in this part of Khams, and they are accompanied by groups of Eight Caityas.

Fig. 16a |

Fig. 16b |

Fig. 16c |

Fig. 17a |

Fig. 17b |

Fig. 18 The second rock carving associated with Wencheng is the “Vairocana/Wencheng Gongzhu Temple”, or Beedo (Bis mda’) Temple, as Amy Heller refers to it. (Figures 17a and 17b). A sculptural maṇḍala of Vairocana and the Eight Bodhisattvas is enshrined in a small temple in Skye rgu, about twenty miles from Jyekundo. According to the National Administrative Units, the temple is called Wencheng Gongzhu Temple (rgya bza’ kong jo mchod khang) because the temple is said to have been built by Wencheng when she rested there for a month. Scholars do not agree with this attribution to Wencheng, because inscriptions state that the carvings were commissioned in 806, about 160 years after the “princess” had traveled through the area.[30] The Beedo Temple thus provides a clear example of how a site can accrete layers of sacred history. Here, a series of stūpas stands by the wayside leading the pilgrims to the holy site. The Eight Caityas there stand in a row and share a pedestal with prayer wheels. A small free standing prayer wheel and a large, square, three-story stūpa stands after the last stūpa in the row.

Fig. 19 The Drölma Lhakang (Glong thang ’Jig rten sgrol ma lha khang) in Denkhog is another remarkable place dedicated to Wencheng; it is accompanied by an ancient maṇi stone field. (Figures 18–20c). The monastery is situated at the banks of the Upper Yangtze River in the historical region of Derge. The temple was purportedly founded by Srong btsan sgam po in 638, and is one of the temples suppressing the supine demoness.[31] As it is well-known —with the help of her knowledge on geomantic divination— “princess” Wencheng attributed Tibet the shape of a demoness resting on her back (srin mo gan rkyal du nyal ba). In order to pacify the land Wencheng defined a number of sites where the demoness should be pinned down by Buddhist temples. The Drölma Lhakang in Khams is one of twelve temples suppressing the demoness’s major limbs, pinning down her left palm. Wencheng herself is said to have visited the site and a small image of Śyāmatārā[32] stored in a strongbox within the temple and only shown to the public once a year is locally believed to be her gift.

As it is tradition, stūpas are accompanying the maṇi stone field (maṇi rdo ’bum; lit. hundred thousand maṇi stones) made of piled maṇi stones (rdo ma ni), plates, rocks, and pebbles inscribed with mantras (sngags). Most feature the six-syllable mantra of Avalokiteśvara, “Oṃ Maṇi Padme Hūṃ,” but other mantras or dhāraṇīs (gzungs) can also be found; some are decorated with images of buddhas and bodhisattvas as well. Maṇi stone fields are typically located at temples and monasteries at mountain passes and road junctions, or at other special sacred sites.

Fig. 20a |

Fig. 20b |

Fig. 20c |

Fig. 21 |

Fig. 22 |

Fig. 22a |

Fig. 23 |

Fig. 23a |

-

3. Observing a New Sacred Space

Fig. 24 |

Fig. 25 |

The main stūpa (Figure 25)

sNa tshogs Rin po che consecrated the large stūpa on August 19, 2003. The characteristic octagonal-shaped middle part classifies the main stūpa (ca. thirty meters high) as a dbyen sdum mchod rten. It stands on three square terraces with integrated prayer wheels. Staircases on all four sides lead to four shrine rooms containing larger-than-life images of Yamāntaka (gshin rje gshed) to the front, Guhyasamāja (gsang ba ’dus pa) to the right, the horse-headed Hayagrīva (rta mgrin) to the back, and Cakrasaṃvara (’khor lo bde mchog) to the left.

Fig. 26 In general, the lion motif is closely connected to (contemporary) stūpas; a pair of white snow lions with a turquoise mane (seng dkar g.yu ral)—painted, carved, or in low relief—often adorn the four sides of the throne (gdan khri). Here, however, the snow lions are absent, as the four entrances occupy their usual place. As shown in Figure 26, four larger-than-life stone lions rest at the corners of the first terrace looking outwards, as if to watch the vicinity, however. This represents a new stylistic creation, hitherto absent in the tradition of Tibetan-style stūpas. The stone lions readily recall the guardian lion sculptures that frequently grace Chinese imperial architectural works such as the Forbidden City in Beijing. The lions are presented in pairs, the male lions have the right front paw on a ball and are placed to the right of the stūpa, the female lions have a cube under the left paw and are placed to the left of the stūpa, and all four lions have large pearls in their partially opened mouths.[37] The adaption of Chinese stylistic elements may be explained by sNa tshogs Rinpoche’s close ties with Beijing which are discussed below.

The 108 Eight Caityas (Figure 27)

Fig. 27 One hundred and eight stūpas (ca. three meters high) surround the ensemble on three sides. Two sets of five groups of Eight Caityas stand vis-à-vis the longitudinal side, and twenty-eight caityas sharing one pedestal stand at the back of the main stūpa. All are whitewashed with a golden superstructure but lack any additional decoration. The vase alcove (sgo khyim) is framed by a golden door decoration (pa tra) accented with jewels. Inside the alcove and behind glass are identical images of the Jo bo Śākyamuni, a very popular figure in Khams. A plate with the name of sponsors is affixed to each caitya. A stone fence with Chinese styled stone lions sitting on the fence posts is erected in front of the caityas.

The idea of a sacred area composed of a central stūpa surrounded by small stūpas and shrines either for relics or for images can be traced back to an old tradition from the Gandhāra region.[38] Early stūpas were designed to enshrine the relics of the Buddha, however, and had no accessible interior. Stūpas that double as a temple were very rare in early Buddhist history. In the Ladakh region of the western Himalaya, large stūpa-temples exist in which a shrine contains an inner stūpa, for example the Great stūpa of Alchi. The Zlum brtsegs lha khang erected in 1421 by Thang stong rGyal po (1361/65–1480/86) in western Bhutan is another remarkable example.[39] Nevertheless, determining whether these ancient stūpa-temples are connected to contemporary monumental stūpas which double as temples requires future research. One example of a Tibetan styled stūpa-temple is the National Memorial Chorten in Thimphu, Bhutan, founded in 1974 to commemorate King ’Jigs med rdo rje dbang phyug (1928‒1972) and shaped as an accessible stūpa that contains Buddhist images on three levels.[40] Another contemporary example of many is the Droden Kunkhyab Chodey Monastery in Salugara, West Bengal, founded in 1988 by the late Ka lu rin po che (1905–1089) and finished one year after his death. It is a bkra shis sgo mang mchod rten, it doubles as a temple and rises thirty meters tall, accompanied by 108 smaller stūpas.[41]

The Interpretation of the new ensemble in Kandze

Fig. 28 Using a dbyen sdum mchod rten dedicated to the unification of the divided sangha as the central monument is quite unusual, as most similar and contemporary ensembles feature the byang chub mchod rten referring to Buddha’s enlightenment, or the bkra shis sgo mang mchod rten symbolizing his turning of the wheel of dharma. Why sNa tshogs Rin po che choose this stūpa type is matter of speculation. One reason could be that some local Tibetans criticized him for his collaboration with the Chinese government. At the time the stūpa was constructed, sNa tshogs Rin po che served as director of the Beijing-based China Tibetan Language Higher Institute of Buddhism, for example. He may have had the intention to unify the local Tibetan sangha with the Chinese Buddhist sangha by this stūpa type; he even collected money for the stūpa from Chinese Buddhist communities. During the opening ceremony in 2003, one could not yet see the supposed unifying effect, however. Some activists are reported to have displayed the Tibetan flag (which is forbidden in China) as a sign for fighting for independence of Tibet from China.[42] About 10 years later—during the time of this survey in 2012—many Tibetans met for a religious event there giving us the impression that over the years the stūpa may have fulfilled its unifying function.

The visual representation of the Mount Sumeru world system (ca. ten meters high) as described in the Abhidharmakośa makes the ensemble highly unusual (Figure 28).[43] In my opinion, the three-dimensional interpretation of the cosmos exudes a feeling of creative fantasy about the past, something not typically seen at a traditional place for worship. Tibetans meeting for religious events there however, signaling that the ensemble not only serves as a unique contemporary pilgrimage site that attracts Chinese Buddhists and other tourists but also functions as an assembly place for the local community. It can thus be interpreted as a new sacred space where locals can practice their religion and tourists can visit likewise.

-

4. Stylistic Influences from Nepal

Fig. 29 Nepal has its own history and typology of stūpas and beside the most significant caityas in Nepalese culture—the mahācaityas of Bodhnāth and Svayambhū—many Nepalese caitya types have developed.[44] At what point in history the Tibetans brought their characteristic Tibeto-Buddhist stūpa tradition to Nepal is a matter of speculation. Niels Gutschow found the first evidence for a Tibetan styled stūpa, locally known as bodhicaitya, in Cvasapābāhā, Kathmandu, built in 1701.[45] Later, this Nepalese version of the Tibetan stūpa became more common in the Kathmandu valley and Gutschow counted eleven examples on the Svayambhū Hill in the 1990s.[46] Since then, the number of Tibetan stūpas have significantly increased. In my own research, I discovered a building boom of the Eight Caityas marking the sacred area around ancient pilgrimage sites like Boudhā and Svayambhū and elsewhere in the Kathmandu valley. Additionally, stūpas pop up wherever Tibetans have established their monasteries or retreat centers, for example at the nunnery Karma Ngedon Osal Choekhorling, in Kathmandu founded in 1993 by Sherab Gyaltsen Rinpoche (b. 1950), or at Samten Phuntsok Ling in Pharping, established in 1982 by the 6th Tharig Rinpoche (1923–1998).

Another region full of contemporary stūpas of different Buddhist traditions is the Monastic Zone of Lumbinī, designed by Kenzo Tange in the 1970s.[47] For example, Sherab Gyaltsen Rinpoche supervised the construction of a huge accessible stūpa designed as a Stūpa of Heaped Lotuses (pad spungs mchod rten) which was completed in 2003. (Figure 29) The wall paintings inside the stūpa depict the life story of the Buddha and show examples for high-quality murals in contemporary Karma Gardri (karma sgar bris) painting style.[48] All these stūpas are, in my opinion, the starting point of what I call the “contemporary Tibetan stūpa architecture” which spread not only back to Tibet but also to Europe. A unique stūpa which, in my opinion, could potentially mark the starting point of what might be termed “contemporary European stūpa architecture” can be found in Benalmádena at the Costa del Sol, Spain.[49]

Fig. 30 A typical Nepalese decoration adapted by most of the Tibetan styled stūpas built in Nepal is the pair of eyes painted on each side of the square harmikā facing the four cardinal directions. They are commonly known as Wisdom Eyes (Sk. vajradṛṣṭi, “vajra sight”) of the primordial Adi Buddha, looking out in the four cardinal directions to symbolize the omniscience (all-seeing) of a Buddha. Between the bows, there is one of the thirty-two marks of the Buddha: a white curl of hair turning to the right, called ūrṇā. When depicted on stūpas it became a round mark. The s-shaped line below the ūrṇā is according to Berhard Kölver “the ray of light” emanating from the ūrṇā.[50] The Wisdom Eyes are a characteristic décor at the Svayambhū and Bodhnāth mahācaityas and they became common for most of the Nepalese caityas, for example at the Dharmadeva caitya in Chabahil (see Figure 30), which Mary Slusser counts among the four oldest and most prestigious stūpas in the Kathmandu valley.[51]

This characteristic decoration found its way to Khams, at the Mchod rten dkarpo (“White Stūpa”) in Lithang, for example (Figure 31a). The large mchod rten is, together with a temple containing a prayer wheel (both ca. 25–30m high), the main attraction in the public park called Mcho dkar spyi gling. In front of the mchod rten, Eight Caityas (ca. 4 m high) are arranged in two groups of four and one-hundred-and-eight byang chub mchod rten (ca. 2.30 m high) encircle the park – all harmikās are decorated with the Wisdom Eyes. By mistake, the s-shaped line below the ūrṇā was transformed into a nose (Figure 31b).

Fig. 31a |

Fig. 31b |

Fig. 32a |

Fig. 32b |

Another stylistic characteristic of the contemporary Tibetan stūpas built in Nepal is the opulent and colourful decoration in base-relief technique covering the ‘throne’, the tapered tiers above, and the ‘vase’ like at this Caityas at Svayambhū hill (Figure 33). Similar ornamentation we found at some stūpas in Derge (Figure 34). Here a row of several groups of Eight Caityas and byang chub mchod rtens accompanied by multi-storey stūpas and small ma ṇi ’khor lo temples are lined alongside the street leading from the Derge printing house to the great Sa skya monastery Derge Gonchen (sDe dge dgon chen)[52]. The stūpas are made of concrete, some of which were still under construction at the time of this survey (2012).

Fig. 33 |

Fig. 34 |

Fig. 35a |

Fig. 35b |

Concluding Remarks

As observed in Khams, the rebuilding of material culture in contemporary Tibet is a vivid revitalization and transformation process. Our visual analysis demonstrates the simultaneous existence of traditional stūpas being copied without striking modifications and new varieties of sacred spaces being created with innovative approaches. In the case of (re-built) monasteries and revitalized pilgrimage sites, stūpas are for the most part designed in a traditional manner congruent with stylistic influences of contemporary Tibetan stūpas that are built in Nepal. This is the continuation (or a revival) of the stylistic influences from Nepal visible at some rock carvings dated to the 8th century and which—together with stylistic influences from China—became dominant in the fourteenth century. Today, the stūpa architecture largely matches with the traditional Tibetan canon, yet certain cases suggest that traditional knowledge about the principles of stūpa construction was not always available. These stūpas generally represent a continuation or repetition of traditions that were forcibly stopped during the Cultural Revolution, although with some minor modifications such as using concrete as the building material.

The innovative stūpa-temple of Natsog Gön, on the other hand, where a large stūpa doubles as a temple, represents a transformation or a re-invention of stūpa architecture and design vis-à-vis those built before the 1950s. Tourists and pilgrims alike visited the site, but the motivations for erecting this kind of new sacred space are not entirely clear as yet. More scholarly observations are necessary to clarify whether the new stūpas aim to draw in sightseers or satisfy existing tourism demands, or if they simply reflect the religious needs of indigenous people. Further, the stūpas at ancient pilgrimage sites associated with Wencheng Gongzhu reveal how sites can accrete layers of sacred history and become acculturated. They also, at first sight, attest to efforts to reestablish the Tibetan religious tradition. Put under the microscope, we could follow Samten G. Karmay, who argues that the present association of many ancient sites with Wencheng is closely linked to a propagandistic pilgrimage guide written for the purposes of heralding ethnic unity between China and Tibet. What we can say with certainty is that the material culture of Tibet—in this case stūpas in Khams—is undergoing a major transformation, one that will impact the general shape of this special region in years to come.

Selected Bibliography

Bagchi, Prabodh Chandra. “The Eight Great Caityas and their Cult.” The Indian Historical Quarterly 17/2 (1941): 223–35.

Behrendt, Kurt A.. The Buddhist Architecture of Gandhāra. Leiden and Boston: Brill Academic Publications, 2004.

Bénisti, Mireille. Stylistics of Buddhist Art in India. New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2003.

Bentor, Yael. “The Content of Stūpas and Images and the Indo-Tibetan Concept of Relics.” The Tibet Journal 28, 1/ 2 (2003): 21–48.

———. Consecration of Images and Stūpas in Indo-Tibetan Tantric Buddhism. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 1996.

———. “Literature on Consecration (Rab gnas).” In Tibetan Literature: Studies in Genre. Edited by José Ignacio Cabezón and Roger R. Jackson, 290–311. Ithaca, New York: Snow Lion Publication, 1996.

———. “In Praise of Stūpas: The Tibetan Eulogy at Chü-Yung-Kuan Reconsidered.” Indo-Iranian Journal 38 (1995): 31‒54.

———. “The Redactions of the Adbhutadharmaparyāya from Gilgit.” The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 11/2 (1988): 21–52.

Booz, Patrick. “‘To Control Tibet, First Pacify Kham’: Trade Routes and ‘Official Routes’ (Guandao) in Easternmost Kham.” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review 5/2 (November 2016): 239–63.

Bue, Erberto Lo and Franco Ricca. The Great Stupa of Gyantse: A Complete Tibetan Pantheon of the Fifteenth Century. London: Serindia Publications, 1993.

Buffetrille, Katia “Some Remarks on Bya Rung Kha Shor and others Buddhist Replicas in A Mdo” In From Bhakti to Bon: Festschrift for Per Kværne. Edited by Hanna Havnevick and Charles Ramble, 133–152. Oslo: Novus, 2015.

Buswell, Robert E. Jr., Donald S. Lopez. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Buston Rin chen grub. “Byang chub chen po’i mchod rten gyi tshad: Measurements for the Stūpa of Great Enlightenment.” In The Collected Works of Bu-Ston, Vol. 14, 551– 558. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture, 1965.

Cüppers, Christoph, Leonard van der Kuijp, and Ulrich Pagel, eds., Handbook of Tibetan Iconometry: A Guide to the Arts of the 17th Century. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2012.

Czaja, Olaf. “The Eye-Healing Avalokiteśvara: A National Icon of Mongolia and its Origin in Tibetan Medicine.” Tibetan and Himalayan Healing. An Anthology for Anthony Aris. Edited by Charles Ramble and Ulrike Roesler, 125–139. Kathmandu: Vajra Publications, 2015.

———. “Some Remarks on Artistic Representations of Bodhnāth Stūpa in Tibet, Mongolia and Buryatia.” In The Illuminating Mirror. Tibetan Studies in Honour of Per K. Sørensen on the Occasion of his 65th Birthday. Edited by Olaf Czaja and Guntram Hazod, 87–100. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 2015.

sDe srid Sangs rgyas rGya mtsho. The Vaiḍūrya dkar po of Sde-srid Saṅs-rgyas-rgya-mtsho: The Fundamental Treatise on Tibetan Astrology and Calendrical Calculations, Vol. 2. New Delhi: T. Tsepal Taikhang, 1971.

Karma pa mKha’ khyab rdo rje. Bde bar gshegs pa’i chos sku’i rten mchog byang chub chen po’i mchod sdong gi cha tshad zhib mor bkod pa tshangs pa’i me long zhes bya ba a sti. Collected Works, Vol. 10, 365‒369. New Delhi: Konchok Lhadrepa, 1993.

Dallapiccola, Anna Libera, ed., The Stupa. Its Religious, Historical and Architectural Significance, Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1980.

Dhandup, Yangdon, Ulrich Pagel, and Geoffrey Samuel, eds. Monastic and Lay Traditions in North-Eastern Tibet. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2013.

Dorjee, Pema. Stupa and its Technology: A Tibeto-Buddhist Perspective. New Delhi: Shri Jainendra Press, 1996.

Ehrhard, Franz-Karl. Buddhism in Tibet and the Himalayas: Texts and Tradition. Kathmandu: Vajra Publications, 2013.

Epstein, Lawrence, ed., Khams pa Histories: Visions of People, Place and Authority:

PIATS 2000: Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the Ninth Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2002.

Germano, David and Nicolas Tournadre. “Simplified Phonetic Transcription of Standard Tibetan.” The Tibetan and Himalayan Library (2003): 1–13, accessed May 9, http://www.thlib.org/reference/transliteration/#!essay=/thl/phonetics/

Goepper, Roger. “The ‘Great Stupa’ at Alchi.” Artibus Asiae 53, 1/ 2 (1993): 111–143.

Goldstein, Melvyn, C. and Matthew T. Kapstein. Buddhism in Contemporary Tibet: Religious Revival and Cultural Identity. Berkley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 1998.

Gruschke, Andreas. The Cultural Monuments of Tibet's Outer Provinces. Kham (2). The Qinghai Part of Kham. Bangkok: White Lotus Press.

Gutschow, Niels. The Nepalese Caitya: 1500 Years of Buddhist Votive Architecture in the Kathmandu Valley (Lumbini International Research Institute Monograph Series I). Stuttgart and London: Edition Axel Menges, 1997.

———. “Chortens (mchod-rten) in Humala: Observations on the Variations of a Building Type in North-western Nepal in May 1990.” Ancient Nepal (1990): 10–21.

Gyantsen, Karma. mDo Khams gnas yig phyogs sgrigs dad bskul lha dbang rnga sgra zhes bya ba bzhugs so. (A Guide to Sacred Places of Mdo Khams), Pe cin: Mi rigs dpe skrun khang, 2005.

Gyatso, Janet. “Letter Magic: A Peircean Perspective on the Semiotics of Rdo Grub-chen’s Dhāraṇī Memory.” In The Mirror of Memory: Reflections on Mindfulness and Remembrance in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism. Edited by Janet Gyatso (Albany: University of New York Press, 1992): 173–214.

Hawkes, Jason and Akira Shimada, eds., Buddhist Stupas in South Asia. Recent Archaeological, Art-Historical, and Historical Perspectives, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Heller, Amy. “Eighth- and Ninth-Century Temples & Rock Carvings of Eastern Tibet”, In: Tibetan Art. Towards a Definition of Style. Edited by Jane Casey Singer and Philip Denwood, 86‒103, 296‒97, London: Laurence King Publishing, 1997.

———. “Buddhist Images and Rock Inscriptions from Eastern Tibet, 7th to 12th Century, Part IV”, In Tibetan Studies. Edited by Ernst Steinkellner, 385‒403. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Science, 1997.

———. “The Lhasa gtsug lag khang: Observations on the Ancient Wood Carvings” Asian Art 2006 https://www.asianart.com/articles/heller2/index.html (accessed March 9 2017).

———. “Early Ninth Century Images of Vairocana from Eastern Tibet.” Orientations 25/6 (1994): 74–79.

———. “Ninth century Buddhist Images Carved at lDan ma brag to Commemorate Tibeto-Chinese Negotiations.” In Tibetan Studies. Edited by Per Kværne. Oslo: The Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture, 1994: 335–349.

Huber, Toni. “Some 11th-Century Indian Buddhist Clay Tablets (tsha-tsha) from Central Tibet.” In Tibetan Studies. Edited by Shoren Ihara and Zuiho Yamaguchi, 493–96. Narita: Naritasan Shinshoji, 1992.

Huber, Toni. The Holy Land Reborn. Pilgrimage & the Tibetan Reinvention of Buddhist India. Chicago and Bonn: The University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Kapstein, Matthew T., ”The Treaty Temple of the Turquoise Grove.“ In: Buddhism between Tibet and China. Edited by Matthew T. Kapstein. Sommerville: Wisdom Publications, 2009: 21–72.

Karmay, Samten G. The Arrow and the Spindle: Studies in History, Myths, Rituals andBeliefs in Tibet. Kathmandu: Mandala Book Point, 1998.

Kolas, Ashild, Monika P. Thowsen. On the Margins of Tibet. Cultural Survival on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2005.

Kölver, Bernhard. Rebuilding a Stūpa: Architectural Drawings of the Svayaṃbhūnāth. Bonn: VGH Wissenschaftsverlag, 1992.

Martin, Dan. “On the Origin and Significance of the Prayer Wheel According to Two Nineteenth-Century Tibetan Literary Sources.” The Journal of the Tibet Society 7 (1987) 13–29.

Maurer, Petra. Die Grundlagen der tibetischen Geomantie dargestellt anhand des 32. Kapitels des Vaiḍūrya dkar po von sde srid Sangs rgyas rgya mtsho (1653‒1705). Ein Beitrag zum Verständnis der Kultur-und Wissenschafts-geschichte Tibets zur Zeit des 5. Dalai Lama Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho (1617‒1682). Halle: International Institute for Tibetan and Buddhist Studies: 2009.

Mills, Martin A. “Re-Assessing the Supine Demoness: Royal Buddhist Geomancy in the Srong btsan sgam po Mythology.” Journal of the International Association of Tibetan Studies 3 (2007): 1–47.

Monier-Williams, Monier. A Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and philologically arranged with special reference to cognate Indo-European languages. Reprint edition.Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1974.

Pakhoutova, Elena A. Reproducing the Sacred Places: the Eight Great Events of the Buddha’s Life and their Commemorative Stūpas in the Medieval Art of Tibet (10th–13th century), PhD diss, University of Virginia, 2009.

Pettit, John Whitney. Mi pham and the Philosophical Controversies of the Nineteenth Century. Boston: Mipham's Beacon of Certainty. Wisdom Publications, 1999.

Pommaret, Françoise. Bhutan: Himalayan Mountain Kingdom. 5th ed. Hongkong: Odyssey Books and Guides, 2006.

Powers, John. History as Propaganda: Tibetan Exiles Versus the People’s Republic of China. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Richardson, Hugh. Tibet and Its History. Boulder: Shambala, 1984.

———.”Mun Sheng Kong Co and Kim Sheng Kong Co: Two Chinese Princesses in Tibet.” Tibet Journal 22/1 (1997): 3–11.

———.”Early Tibetan Inscriptions. Some Recent Discoveries”. The Tibet Journal 12/2 (1987): 3-15.

Roth, Gustav. “Symbolism of the Buddhist Stupa.” In Stupa: Cult and Symbolism. Edited by Franz-Karl Ehrhard, Kimiaki Tanaka, and Lokesh Chandra, 9–33. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan, 2009.

Sakya, J., J. Emery. Princess in the Land of Snows. The Life of Jamyang Sakya in Tibet. Boston: Shambala, 1990.

Schneider, Nicola “The Monastery in a Tibetan Pastoralist Context. A Case Study from Kham Minyag.” Études Mongoles et Sibériennes, Centrasiatiques et Tibétaines 47 (2016): 1–18, accessed May 9, 2019, http://emscat.revues.org/2798

Schopen, Gregory. Figments and Fragments of Mahayana Buddhism in India: More Collected Papers. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2005.

Schrempf, Mona. “The Earth-ox and the Snowlion.” In Toni Huber, ed., Tibetan Revival in Modern Amdo: Society and Culture During the Late 20th Century. (PIATS, Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 2002): 147–171.

Seegers, Eva. “The Innovative Stūpa Project in Andalusia, Spain: A Discussion on Visual Representations of Tibetan Buddhist Art in Europe.” DISKUS. The Journal of the British Association for the Study of Religions (BASR) 17/3 (2015): 18–39, accessed May 9, 2019, http://diskus.basr.ac.uk/index.php/DISKUS/article/view/78

———. “Two Stūpas of ‘Princess’ Wencheng: A Comparative Study on Two Ancient Terrace Stūpas in Eastern Tibet.” PIATS 2013: Architecture and Conservation: Proceedings of the Ninth Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Journal of Comparative Cultural Studies in Architecture: Tibet 8 (2015): 52–63, accessed May 9, 2019,

———. “Visual Expressions of Buddhism in Contemporary Society: Tibetan Stūpas Built by Karma Kagyu Organisations in Europe.” PhD diss., Canterbury Christ Church University, 2011.

Skorupski, Tadeusz. “Two Eulogies of the Eight Great Caityas.” The Buddhist Forum 6 (2001): 37–55.

Slusser, Mary Shepherd. Nepal Mandala: A Cultural Study of the Kathmandu Valley. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1982.

Snellgrove, David L. and Hugh Richardson. A Cultural History of Tibet (3rd ed). Bangkok: Orchid Press, 2003.

Sørensen, Per K. Tibetan Historiography: The Mirror Illuminating the Royal Genealogies. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 1994.

Tsering, Pema. “Epenkundliche und historische Ergebnisse einer Reise nach Tibet im Jahr 1980.“, Zentralasiatische Studien (1982): 16–18, 349–404.

Turek, Maria. In This Body and Life: The Religious and Social Significance of Hermits and Hermitages in Eastern Tibet Today and During Recent History. Ph.D. Thesis, Berlin: Humboldt Universität, 2013.

Wangchuk, Karma “Dzongs and Gompas in Bhutan” In The Buddhist Monastery. A Cross-Cultural Survey. Edited by Pierre Pichard and F. Lagirarde. Paris: École-Franҫaise d’ Extrême-Orient, 2003: 265‒282.

Wangmo, Sonam “A Study of Written and Oral Narratives of Lhagang in Eastern Tibet” Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines 45 (2017): 69–88.

Warner, Cameron David “Miscarriage of History. Wencheng Gongzhu and Sino-Tibetan Historiography”, Inner Asia 13 (2011): 239‒64.

———. “An Introduction to the Vairocana/Wencheng Gongzhu Temple”, The Tibetan and Himalayan Library (2010), accessed May 9, 2019, http://places.thlib.org/features/15476/descriptions/85#ixzz4jlbOqGf3

Whitfield, Susan. Life Along the Silk Road. University of California Press, 1999.

———. “Was there a Silk Road?” Asian Medicine 3 (2007): 201–13.

Wylie, Turrel V. “A Standard System of Tibetan Transcription.” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 22 (1959): 261‒67.

Footnotes

1. This essay is the expanded version of a paper presented at the 14th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies (IATS), University of Bergen, Norway, June 21–24, 2016. Data was collected during research mission to Khams in 2012. I thank the private sponsors for supporting this research. Also many thanks to Amy Heller for taking on the task of editing this PIATS 2016 publication on Tibetan art. Thanks also due to Lindsey E. DeWitt for carefully proofreading my English.

2. Conventions used in this paper: Tibetan terms have been transliterated according to the system of Turrell V. Wylie, “A Standard System of Tibetan Transcription,” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 22 (1959): 261‒67. Common Tibetan terms are presented in phonetic transcription based on the THL Simplified Phonetic Transcription of Standard Tibetan by David Germano and Nicolas Tournadre, “Simplified Phonetic Transcription of Standard Tibetan,” The Tibetan and Himalayan Library (2003): 1–13. The wish of the editor for easily readable names of places and monasteries was expressed by preferring the phonetic transcription. Transliterations are given in brackets at first occurrence. The Sanskrit form is also given in diacritics on occasion. Words that have already been adapted to English, such as mani wheel, are used in this way.

3. The Sanskrit terms stūpa and caitya originally held different meaning and referred to different kind of religious monuments: stūpa enshrine relics, and caitya commemorate sacred sites. Scholars today employ the terms caitya and stūpa as synonyms, using both to denote memorials (with or without relics). The term stūpa has been translated as “a knot or tuft of hair, the upper part of head, crest, top, summit,” and alternatively “a heap or pile of earth, or bricks etc.” (Monier-Williams, A Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1974: 1260). The stem stūp- means “to heap up, pile, erect,” but there are differing opinions on whether this is the root from which the term stūpa derives. The term caitya carries the meaning of “a funeral monument or pyramidal column containing the ashes of deceased persons, sacred tree (especially a religious fig tree) growing on a mound, hall or temple or place of worship.” We know from Tibetan sources that the mchod rtens contain five types of relics. See, for example, Gustav Roth, “Symbolism of the Buddhist Stupa,” in Stupa: Cult and Symbolism, edited by Franz-Karl Ehrhard, Kimiaki Tanaka, and Lokesh Chandra (New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan, 2009), 65; and Yael Bentor, “The Content of Stūpas and Images and the Indo-Tibetan Concept of Relics,” The Tibet Journal 28, 1/2 (2003): 21–48.

4. The area inhabited by ethnic Tibetans, now part of China, is differentiated into two broad categories known as “political Tibet” and “ethnographic” Tibet. “Political Tibet” is the equivalent to the present-day Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR), and “ethnographic Tibet” covers the historical areas of Khams and Amdo, today part of Sichuan, Qinghai, Gansu, and Yunnan provinces. See Hugh Richardson, Tibet and Its History (Boulder: Shambala, 1984): 1–2; Melvyn C. Goldstein and Matthew T. Kapstein, Buddhism in Contemporary Tibet: Religious Revival and Cultural Identity (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998): 4–5. On the trade routes, see Susan Whitfield, Life Along the Silk Road (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999); Whitfield, “Was there a Silk Road?” Asian Medicine 3 (2007): 201–13; and Patrick Booz, “‘To Control Tibet, First Pacify Kham’: Trade Routes and ‘Official Routes’ (Guandao) in Easternmost Kham,” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review 5/2 (November 2016): 239–63.

5. See, for example, Ashild Kolas and Monika P. Thowsen, On the Margins of Tibet: Cultural Survival on the Sino Tibetan Frontier (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005); Yangdon Dhandup, Ulrich Pagel, and Geoffrey Samuel, eds., Monastic and Lay Traditions in North-Eastern Tibet (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2013); Maria Turek, In This Body and Life: The Religious and Social Significance of Hermits and Hermitages in Eastern Tibet Today and During Recent History, PhD Thesis (Berlin: Humboldt Universität, 2013); Lawrence Epstein, ed., Khams pa Histories: Visions of People, Place and Authority: PIATS 2000: Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the Ninth Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2002); Andreas Gruschke, The Cultural Monuments of Tibet's Outer Provinces. Kham (2). The Qinghai Part of Kham (Bangkok: White Lotus Press, 2004); Amy Heller, “Eighth- and Ninth-Century Temples and Rock Carvings of Eastern Tibet,” in Tibetan Art: Towards a Definition of Style, edited by Jane Casey Singer and Philip Denwood (London: Laurence King Publishing, 1997): 86‒103, 296‒97; Amy Heller, “Buddhist Images and Rock Inscriptions from Eastern Tibet, 7th to 12th Century, Part IV,” in Tibetan Studies, edited by Ernst Steinkellner (Vienna: Austrian Academy of Science, 1997): 385‒403; and Nicola Schneider, “The Monastery in a Tibetan Pastoralist Context: A Case Study from Kham Minyag,” études Mongoles et Sibériennes, Centrasiatiques et Tibétaines 47 (2016): 1–18, http://emscat.revues.org/2798 (accessed March 7, 2017). Changhong Zhang and others from Sichuan University in Chengdu are currently investigating the research of the cultural relics of Yushu county. Changhong Zhang, “A Rock Carving of the Life of the Buddha and Its Tibetan Inscription that were Recently Discovered in Lebkhog, Yushu, Qinghai,” Conference paper, International Conference on Tibetan History and Archaeology Religion and Art (7th‒17th c.), July 13‒15, 2013, Center for Tibetan Studies of Sichuan University, Chengdu, China.

6. Andreas Gruschke, The Cultural Monuments of Tibet's Outer Provinces, Kham (2). The Qinghai Part of Kham.(Bangkok: White Lotus Press, 2004):82–85; Eva Seegers, “Two Stūpas of ‘Princess’ Wencheng: A Comparative Study on Two Ancient Terrace Stūpas in Eastern Tibet,” PIATS 2013: Architecture and Conservation: Proceedings of the Ninth Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Journal of Comparative Cultural Studies in Architecture: Tibet 8 (2015): 52–63; Tibet Heritage Fund, “Yushu Lab Pendhu Stupa.” THF 2006 Annual Report (Lhasa and Berlin: Tibet Heritage Fund, 2006): 5, http://www.tibetheritagefund.org/media/download/annualreport06s.pdf (accessed May 9, 2019).

7. Goldstein and Kapstein, Buddhism in Contemporary Tibet: Religious Revival and Cultural Identity. (Berkley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 1998): 1–14.

8. For example, Gustav Roth, “Symbolism of the Buddhist Stupa,” in Stupa: Cult and Symbolism, edited by Franz-Karl Ehrhard, Kimiaki Tanaka, and Lokesh Chandra (New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan, 2009):9–33; Anna Libera Dallapiccola, (ed.) The Stupa. Its Religious, Historical and Architectural Significance, (Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1980); Hawkes, Jason and Akira Shimada (eds.) Buddhist Stupas in South Asia. Recent Archaeological, Art-Historical, and Historical Perspectives, (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2009).

9. Yael Bentor, “In Praise of Stūpas: The Tibetan Eulogy at Chü-Yung-Kuan Reconsidered,” Indo-Iranian Journal 38 (1995): 34‒57; Yael Bentor, “The Redactions of the Adbhutadharmaparyāya from Gilgit,” The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 11/2 (1988): 21–52;

10. Geomantic instructions appear in the thirty-second chapter of the Vaiḍūrya dkar po of Sde-srid Saṅs-rgyas-rgya-mtsho (The fundamental treatise on Tibetan astrology and calendrical calculations) by sDe srid Sangs rgyas rgya mtsho (1653‒1705).sDe srid Sangs rgyas rgya mtsho, TheVaiḍūrya dkar po of Sde-srid Saṅs-rgyas-rgya-mtsho: The Fundamental Treatise on Tibetan Astrology and Calendrical Calculations (New Delhi: T. Tsepal Taikhang, 1971), vol. 2, fol. 21rl–30r4. A translation into German may be found in Petra Maurer, Die Grundlagen der tibetischen Geomantie dargestellt anhand des 32. Kapitels des Vaiḍūrya dkar po von sDe srid Sangs rgyas rgya mtsho (1653‒1705). Ein Beitrag zum Verständnis der Kultur-und Wissenschaftsgeschichte Tibets zur Zeit des 5. Dalai Lama Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho (1617‒1682) (Halle: International Institute for Tibetan and Buddhist Studies, 2009), 188–89. Examples of unsuitable sites for stūpas include grasslands with stones, places where nāga, scary deities, and ’dre demons reside, and deep gorges at the edge of an earth fissure. A stūpa should also not be located in the east, as the nāga king lingers there and would be angered if a foundation stone is placed there and, in retribution, would destroy a place in the west.

11. On the content of stūpas and their consecration, see Yael Bentor, “The Content of Stūpas and Images and the Indo-Tibetan Concept of Relics,” The Tibet Journal 28, 1/2 (2003): 21–48.

12. See Eva Seegers “Two Stūpas of ‘Princess’ Wencheng: A Comparative Study on Two Ancient Terrace Stūpas in Eastern Tibet.” PIATS 2013: Architecture and Conservation: Proceedings of the Ninth Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Journal of Comparative Cultural Studies in Architecture: Tibet 8 (2015): 52–63. https://www.academia.edu (accessed May 9, 2019).

13. For a critical and interesting discussion on the eight sites of the Buddha and their connection to the aṣṭamahāsthānacaitya see Toni Huber, The Holy Land Reborn. Pilgrimage & the Tibetan Reinvention of Buddhist India. (Chicago and Bonn: The University of Chicago Press, 2008): 27–36. In footnote 50, page 380, Huber touches on many interesting questions related to the Eight Caityas as they may be understood in Tibet. However, I cannot confirm his claim that sets of aṣṭamahāsthānacaityas were hardly built in Tibet as “a public object of popular pilgrimage”—at least this does not apply to today’s Khams.

14. Prabodh Chandra Bagchi, “The Eight Great Caityas and their Cult,” The Indian Historical Quarterly 17/2 (1941): 223–35; Tadeusz Skorupski, “Two Eulogies of the Eight Great Caityas,” The Buddhist Forum 6 (2001): 37–55.

15. Elena A. Pakhoutova, Reproducing the Sacred Places: The Eight Great Events of the Buddha’s Life and their Commemorative Stūpas in the Medieval Art of Tibet (10th–13th century), PhD dissertation (University of Virginia, 2009): 155.

16. The Tibetan terms are based on Karma pa mKha’ khyab rdo rje. Bde bar gshegs pa’i chos sku’i rten mchog byang chub chen po’i mchod sdong gi cha tshad zhib mor bkod pa tshangs pa’i me long zhes bya ba a sti. Collected Works, vol. 10 (New Delhi: Konchok Lhadrepa, 1993): 365‒369.

The basic structure of the Indian stūpas of the Mauryan period (fourth to second centuries BCE) consisted mainly of a circular base (medhī), a hemispherical dome (anda), and a square (harmikā) topped with one or several flights of umbrellas (chattra or chattravali) and crowned with a vase (kalasa) or gem (maṇi). When the stūpa arrived in Tibet, its architecture had already gone through major developments. The earliest stūpas in Tibet presumably consisted of a square platform and five square tapered tiers with a tall dome on top. The superstructure was made from a series of thirteen wheels or rings topped with a half moon, a sun disc, and a drop. In addition to unique monuments like the gigantic dPal ’khor mchod rten of rGyal rtse, completed around 1427, the “Eight Great Location Caityas” became very popular in Tibet. See for example, Mireille Bénisti, Stylistics of Buddhist Art in India. (New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2003): 6; Snellgrove and Richardson, A Cultural History of Tibet, (3rd ed). (Bangkok: Orchid Press, 2003): 89; and Erberto Lo Bue and Franco Ricca, The Great Stupa of Gyantse: A Complete Tibetan Pantheon of the Fifteenth Century (London: Serindia Publications, 1993).

17. On the eight Tibetan stūpas as explained by Grags pa rgyal mtshan, see Yael Bentor, “In Praise of Stūpas: The Tibetan Eulogy at Chü-Yung-Kuan Reconsidered,” Indo-Iranian Journal 38 (1995): 34‒57; and Buston Rin chen grub, “Byang chub chen po’i mchod rten gyi tsad: Measurements for the Stūpa of Great Enlightenment,” in The Collected Works of Bu-Ston, vol. 14 (New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture, 1965): 551–58. On the Tibetan and Chinese translations of the Vimaloṣṇīṣa-Dhāraṇīs, see Gregory Schopen, Figments and Fragments of Mahayana Buddhism in India: More Collected Papers, (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2005): 314–344; and sDe srid Sangs rgyas rGya mtsho, The Vaiḍūrya dkar po of Sde-srid Saṅs-rgyas-rgya-mtsho: The Fundamental Treatise on Tibetan Astrology and Calendrical Calculations, Vol. 2 (New Delhi: T. Tsepal Taikhang, 1971). The richly illustrated handbook Cha tshad kyi dpe ris Dpyod ldan yid gos (‘Illustrations of Measurements: A Refresher for the Cognoscenti’) authored by sDe srid Sangs rgyas rgya mtsho in about 1687 contains many examples of how to design, scale and construct stūpas. See Christoph Cüppers, Leonard van der Kuijp, and Ulrich Pagel, eds., Handbook of Tibetan Iconometry: A Guide to the Arts of the 17th Century. (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2012): plates 288–303.

18. For the geographical location, see Buddhist Resource Center, “li thang dgon chen” https://www.tbrc.org/#!rid=G400 (accessed May 8, 2019).

19. For the geographical location, see Buddhist Resource Center, “zhe chen dgon” https://www.tbrc.org/#!rid=G20 (accessed May 8, 2019).

20. “Maṇi wheel” (or, as it is commonly called in English language, the “prayer wheel”) derives from the abbreviation of the mantra of Avalokiteśvara, “Oṁ Maṇi Padme Hūṁ,” which is the most common mantra written or printed on paper and wrapped around the wooden central axis of the wheels. As Dan Martin points out, “the term ‘prayer wheel’ is by no means a direct translation of any Tibetan term. The texts speak of wheels (’khor-lo), hand wheels (lag-’khor), or dharma wheels (chos-’khor), but they are commonly referred to as ‘maṇi wheels’ (ma-ṇi ’khor-lo).” For more information on the origins of the wheels (their actual use and the benefits of their use), see Dan Martin, “On the Origin and Significance of the Prayer Wheel According to Two Nineteenth-Century Tibetan Literary Source,” The Journal of the Tibet Society 7 (1987) 13–29.

21. For example, at Bodh Gayā or Ratnagirī, India, hundreds of votive stūpas have been built. See Mireille Bénisti, Stylistics of Buddhist Art in India. (New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2003): 205–327.

22. Personal communication with resident monks at Dka’ brag, September 2012.

23. As Cameron David Warner points out, there are stories about Wencheng in Chinese communist historiographies, in Tibetan exiles’ historiography, in Central Tibetan historiography, and in local narratives. Warner, “Miscarriage of History: Wencheng Gongzhu and Sino-Tibetan Historiography,” Inner Asia 13 (2011): 239‒64. On Wencheng Gongzhu as one of several Tang princess who were forced to marry a ruler in order to tie the contacts to a country of interest, see Matthew T. Kapstein, “The Treaty Temple of the Turquoise Grove,” in Buddhism between Tibet and China, edited by Matthew T. Kapstein (Sommerville: Wisdom Publications, 2009): 21–72; John Powers, History as Propaganda: Tibetan Exiles Versus the People’s Republic of China (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004): 30–38; and Hugh Richardson, “Mun Sheng Kong Co and Kim Sheng Kong Co: Two Chinese Princesses in Tibet,” Tibet Journal 22 /1 (1997): 3–11. On Buddhist images and rock inscriptions in Khams, and possible travel routes Wencheng Gongzhu might have taken, see Amy Heller, “Eighth- and Ninth-Century Temples & Rock Carvings of Eastern Tibet;” Amy Heller, “Buddhist Images and Rock Inscriptions from Eastern Tibet, 7th to 12th Century, Part IV;” and Amy Heller, “The Lhasa gtsug lag khang: Observations on the Ancient Wood Carvings,” Asian Art (2006), https://www.asianart.com/articles/heller2/index.html (accessed May 9, 2019). For more information on the propagandistic pilgrimage guide, refer to Samten G. Karmay, The Arrow and the Spindle: Studies in History, Myths, Rituals and Beliefs in Tibet (Kathmandu: Mandala Book Point, 1998): 59. For information on Wencheng Gongzhu, see Buddhist Resource Center, “rgya bza’ kong jo” https://www.tbrc.org/#!rid=P8116 and The Treasury of Lives “Wencheng Kongjo” https://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Wencheng-Kongjo/10811 (accessed May 9, 2019). For information on Srong btsan sgam po, see Buddhist Resource Center,“srong btsan sgam po” https://www.tbrc.org/#!rid=P8067 (accessed May 9, 2019). For information on Srong btsan sgam po’s Nepalese wife, bal bza’ khri btsun, see Buddhist Resource Center, “bal bza’ khri btsun” https://www.tbrc.org/#!rid=P1KG5401 (accessed May 9, 2019).

24. See Eva Seegers “Two Stūpas of ‘Princess’ Wencheng: A Comparative Study on Two Ancient Terrace Stūpas in Eastern Tibet.” PIATS 2013: Architecture and Conservation: Proceedings of the Ninth Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Journal of Comparative Cultural Studies in Architecture: Tibet 8 (2015): 52–63.

25. For example, at Bodh Gayā or Ratnagirī, India, hundreds of votive stūpas have been built. See Mireille Bénisti, Stylistics of Buddhist Art in India. (New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2003): 205–327.

26. Eva Seegers “Two Stūpas of ‘Princess’ Wencheng: A Comparative Study on Two Ancient Terrace Stūpas in Eastern Tibet.” PIATS 2013: Architecture and Conservation: Proceedings of the Ninth Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Journal of Comparative Cultural Studies in Architecture: Tibet 8 (2015): 52–63.

27. Both texts—the dPal lha sgang gi gnas bstod and the Yang gsang mkha’ ’gro ’i thugs kyi ti ka las / lHa dga’ ring mos gnas kyi dkar chag (author unknown)—were published by Karma Gyantsen. mDo Khams gnas yig phyogs sgrigs dad bskul lha dbang rnga sgra zhes bya ba bzhugs so. A Guide to Sacred Places of Mdo Khams (Pe cin: Mi rigs dpe skrun khang, 2005): 288–314. For detailed information see Sonam Wangmo “A Study of Written and Oral Narratives of Lhagang in Eastern Tibet” Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines 45 (2017): 69–88.

28. Birthplace of the 16. Karma pa Rang byung Rigpa’i rDorje (1924 – 1981).

29. Amy Heller, “Buddhist Images and Rock Inscriptions from Eastern Tibet, 7th to 12th Century” In: Tibetan Studies, edited by Ernst Steinkellner (Vienna: Austrian Academy of Science, 1997): 387, and Pema Tsering, “Epenkundliche und historische Ergebnisse einer Reise nach Tibet im Jahr 1980,” Zentralasiatische Studien (1982): 363. On the date of the inscriptions, see also Hugh Richardson. “Early Tibetan Inscriptions. Some Recent Discoveries.” The Tibet Journal 12/2 (1987): 3–15.

30. See the geographical location of the temple at The Tibetan and Himalayan Library, “Wencheng Gongzhu Temple” http://places.thlib.org/features/15476 (accessed May 9, 2019). For a stylistic analysis, see Amy Heller, “Early Ninth Century Images of Vairocana from Eastern Tibet,” Orientations 25/6 (1994): 74–79; and Amy Heller, “Ninth century Buddhist Images Carved at lDan ma brag to Commemorate Tibeto-Chinese Negotiations,” in Tibetan Studies, edited by Per Kværne (Oslo: The Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture, 1994): 335–349. For an introduction to the temple and further references, see Warner, “Vairocana/Wencheng Gongzhu Temple.” The Tibetan and Himalayan Library (2010), http://places.thlib.org/features/15476/descriptions/85#ixzz4mF84WSPE (accessed December 12, 2018).

31. See Per K. Sørensen, Tibetan Historiography: The Mirror Illuminating the Royal Genealogies (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 1994): 261–263 and 560. See Janet Gyatso, “Down with the demoness: reflections on a feminine ground in Tibet,” Tibet Journal XII–4 (1987): 38–53, and Martin A. Mills, “Re-Assessing the Supine Demoness: Royal Buddhist Geomancy in the Srong btsan sgam po Mythology,” Journal of the International Association of Tibetan Studies 3 (2007): 1–47.

32. David P. Jackson mentioned that this venerable image has purportedly once been the possession of the Indian king Ajataśatru. See David P. Jackson, A Saint in Seattle: The Life of the Tibetan Mystic Dezhung Rinpoche (Boston: Wisdom Publication, 2003): 48 and footnote 185.

33. For the geographical location, see Google Maps, https://www.google.de/maps/@33.0635134,98.3108745,13z (accessed May 9, 2019). For information on ’Ju Mi pham rgya mtsho’s life and work, see John Whitney Pettit, Mi pham and the Philosophical Controversies of the Nineteenth Century (Boston: Mipham’s Beacon of Certainty, Wisdom Publications, 1999).

34. Olaf Czaja, “The Eye-Healing Avalokiteśvara: A National Icon of Mongolia and its Origin in Tibetan Medicine,” in Tibetan and Himalayan Healing. An Anthology for Anthony Aris, edited by, Charles Ramble and Ulrike Roesler, (Kathmandu: Vajra Publications, 2015): 125–139.

35. 360 m length x 14 m height x 3 m width. See Records of Cultural Relics in SNe-gdong Country (Cultural Administration of the Tibet Autonomous Region, 2008): 49–50.

36. For information of Beri Gon, founded in 1649, refer to Buddhist Resource Center, “be ri dgon” https://www.tbrc.org/#!rid=G380 (accessed May 9, 2019).

37. According to Mona Schrempf, there exists a Tang source describing the lion holding a “pearl” in his mouth, which is, according to a folk narrative, made of iron in order to appease demonic forces. Mona Schrempf, “The Earth-ox and the Snowlion.” 147– 71. In Toni Huber, ed., Tibetan Revival in Modern Amdo: Society and Culture During the Late 20th Century. (PIATS, Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 2002): 166.

38. Kurt A. Behrendt, The Buddhist Architecture of Gandhāra (Leiden and Boston: Brill Academic Publications, 2004): 27.

39. For more details on the Dumtseg Lhakhang, refer to Françoise Pommaret, Bhutan: Himalayan Mountain Kingdom (Hong Kong: Odyssey Books and Guides, 2006): 138; and Karma Wangchuk, “Dzongs and Gompas in Bhutan,” in The Buddhist Monastery: A Cross-Cultural Survey, edited by Pierre Pichard and F. Lagirarde (Paris: École-Franҫaise d’ Extrême-Orient, 2003): 267. For the life-dates of Thangtong Gyalpo, see Buddhist Resource Center, “thang stong rgyal po” https://www.tbrc.org/#!rid=P2778 (accessed May 9, 2019). For the stūpa-temples in Ladakh, see Roger Goepper, “The ‘Great Stupa’ at Alchi,” Artibus Asiae 53, 1/ 2 (1993): 111–143.

40. The National Memorial Chorten was supervised by Dungtse Rinpoche (gDung sras, 1931‒2011), son of Dudjom Rinpoche (Bdud ’joms, 1904‒1987), and follows the rNying ma tradition. For more on this, see Françoise Pommaret, Bhutan: Himalayan Mountain Kingdom,. (Hongkong: Odyssey Books and Guides, 2006): 138.

41. Eva Seegers, Visual Expressions of Buddhism in Contemporary Society: Tibetan Stūpas Built by Karma bKa’ brgyud Organisations in Europe, PhD dissertation (Canterbury Christ Church University, 2011): 173–4.

42. International Campaign for Tibet, “Tibetan Resistance to Repressive Measures Continues in Kandze.” https://www.savetibet.org/tibetan-resistance-to-repressive-measures-continues-in-kandze/ (accessed December 15, 2018).

43. For information on Mount Sumeru, see Robert E. Buswell, Jr. and Donald S. Lopez, The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2014): xxxi–xxxii, 2123–4.

44. Niels Gutschow, The Nepalese Caitya: 1500 Years of Buddhist Votive Architecture in the Kathmandu Valley. Lumbini International Research Institute Monograph Series I. (Stuttgart and London: Edition Axel Menges, 1997): 305. On the mahācaityas Bodhnāth and Svayambhū, see also Christoph Cüppers “Zhabs-dkar Bla-ma Tshogs-drug rang-grol’s visit to Nepal and his Contribution to the Decoration of the Bodhnāth Stūpa”, Nepal. Past and Present, edited by Gérard Toffin (New Delhi: Sterling Publishers, 1993): 1951–58; Franz-Karl Ehrhard, Buddhism in Tibet & the Himalayas. Texts and Traditions (Vajra Publications, 2013); Alexander von Rosspatt “The Sacred Origins of the Svayambhūcaitya and the Nepal Valley: Foreign Speculations and Local Myth”, Journal of the Nepal Research Centre 13 (2009): 33–89.

45. Niels Gutschow, op. cit. 1997: 302. According to Franz-Karl Ehrhard, the 16th century is the generally accepted date for the arrival of the first Tibetan settlers in the Everest area. See Franz-Karl Ehrhard, op.cit, 2013: 183.

46. See Niels Gutschow, ibid.1997: 302–7.

47. See Kai Weise, The Sacred Garden of Lumbini: Perceptions of Buddha’s Birthplace. Published by the UNESCO, France, (Kathmandu: Hillside Printing Press, 2013): 112–14.

48. Examined by the author in February 2010 and February 2011. For details on the sgar bris painting style refer to Jackson, 1996.

49. This byang chub mchod rten is designed as a stūpa-temple that has a height of thirty-three meters and a meditation room of more than one hundred square meters, making it one of Europe’s largest. It was spiritually supervised by the Nepal-based Bhutanese master sLob dpon Tse chu rin po che (1918‒2003) and officially inaugurated in 2003 by Źwa dmar rin po che (1952–2014). See Eva Seegers, “The Innovative Stūpa Project in Andalusia, Spain: A Discussion on Visual Representations of Tibetan Buddhist Art in Europe,” DISKUS. The Journal of the British Association for the Study of Religions (BASR) 17/ 3 (2015): 18–39. http://diskus.basr.ac.uk/index.php/DISKUS/article/view/78 (accessed May 9, 2019).

50. Bernhard Kölver, Rebuilding a Stūpa: Architectural Drawings of the Svayaṃbhūnāth. (Bonn: VGH Wissenschaftsverlag, 1992):129.

51. Mary Shepherd Slusser, Nepal Mandala: A Cultural Study of the Kathmandu Valley (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1982): 276.

52. Buddhist Resource Center, “sde dge dgon chen” https://www.tbrc.org/#!rid=G193 (accessed May, 9 2019).

53. For other replicas of Boudhā see Katia Buffetrille „Some Remarks on Bya Rung Kha Shor and others Buddhist Replicas in A Mdo,“ in From Bhakti to Bon: Festschrift for Per Kværne, edited by Hanna Havnevick and Charles Ramble (Oslo: Novus, 2015): 133–152; and Olaf Czaja “Some Remarks on Artistic Representations of Bodhnāth Stūpa in Tibet, Mongolia and Buryatia,” in The Illuminating Mirror. Tibetan Studies in Honour of Per K. Sørensen on the Occasion of his 65th Birthday, edited by Olaf Czaja and Guntram Hazod. (Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 2015): 87–100.

HOME | TABLE OF CONTENTS | INTRODUCTION

asianart.com