West

meets East: Making a Murti in Kathmandu

by Karla Refojo[1]

May 12, 2006

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

For the last five years, I have been working in the

Kathmandu Valley with Newar bronze casters to create a larger than life-sized

murti, or sacred statue. This article is a brief account of my experiences

and the incredible and challenging process by which a statue was created

and a sculptor was transformed.

The Newar artisans of Kathmandu are among the best in the world, most

notably for their expertise in the lost wax process of bronze casting.

The tradition of metal casting in Nepal dates back from the Licchavi

period (300-800 C.E.) The conditions in which Newars work today and

their techniques have remained largely unchanged since ancient times.

They work in poorly lit, small spaces with inadequate ventilation, yet

they create unparalleled masterpieces of workmanship and beauty. |

In 2001 I began work on the “Rudi” statue

in a small house at the base of the Swayambunath stupa. I worked alongside

Ravindra Jyapu, a well known teacher at the Fine Arts College in Kathmandu

and his son Rajendra. This Jyapu family is unique in that they are traditionally

farmers by caste [3], but through their passion and perseverance they are

accomplished sculptors in their own right. They have trained themselves

exquisitely in the complex and daunting process of lost wax bronze casting.

Working in tandem with another artist is a challenging event for someone

used to working alone. Here in Kathmandu, artists are admirably accustomed

to working with various people specializing in different stages of the

process. Language, cultural barriers and working style sometimes posed

a challenge between Ravindra and myself. In addition, this was an unusual

project in that I was aiming to achieve a portrait of a spiritual person

to be used for meditation practice. My intent was for it to reflect

not only the physical likeness and humanity of Rudi, but — equally

as important — his energy. My vision was difficult to convey to

Ravindra with his more classical approach. We successfully dealt with

this by dividing the work – I took the head and he worked on the

torso - and through our steadfast joint efforts together we produced

a cohesive and powerful piece. |

| With the second round of wax modeling I was able to further perfect

the statue. Working with Rajendra now, and with the help of one of Ravindra’s

top students, Vijay Maharjan, the second version was even finer than the

first. Rajendra developed his own techniques to mitigate the problems

caused by the weather. He coated the inside walls of the wax with a few

thin coats of plaster which enabled the wax to keep it's shape despite

the heat. This was quite a successful innovation in the traditional field

of casting in Nepal.

In order to cast such a large statue in bronze, we again had to cut the statue into sections. Given the circumstances, we did it in surprisingly few parts: head, torso, two arms, legs and the base.

Next came the casting. (see figs 6, 7) The Rudi statue was cast using the five-metal combination known as Pancha Dhatu (five metals). We chose it because it is traditionally used in some Indian traditions to create sacred images [5]. It combines gold, silver, copper, zinc and tin, each of which correlate vibrationally to planetary energies, similar to the way gemstones are used in the Vedic system.

During casting, this esoteric combination of molten bronze was poured into the mold. The consistency of the heat of the metal and the smoothness of its filling is crucial. Variations in heat or timing can drastically impact the statue – leaving holes, marks or other more disastrous problems. Achieving this is particularly difficult given the conditions we were working in. The homemade oven, complete with half-baked bricks that would occasionally explode from the fire, miraculously held the heat evenly and steadily. After the molds were cooled, they were broken open to reveal the sections of the bronze statue inside.(fig 8) Because each mold has to be broken to release the statue, every statue made using this process is one of a kind.

|

Rajendra accommodated our desire for a more natural final patina by using Pancha Dhatu for joining and touch ups on the statue. This was innovative as brass is commonly used for welding, with small exceptions of the more traditional wiring methods of silver or copper. Pancha Dhatu is harder to work with but the result was far superior because of it.

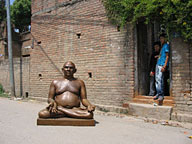

The statue is now ready to leave its birthplace at the base of Swayambunath stupa and go on to America. (fig. 12- 15) It carries inside it a wealth of tradition and artistic devotion that is unique to the Newar people of the Kathmandu valley. This experience has greatly transformed and enriched my entire life and my art.

There is such magic embedded here that regardless of the artistic technique I engage in—though sometimes frustrating— it is an alchemical process that reveals amazing possibilities. I am currently working with another Newar artist, who is extraordinarily gifted in the art of repousse, Rajendra Bajracharya from Patan. My connection to the Newar people and their ancient artistic traditions continues to unfold.

For this ongoing experience I am ever grateful to my teacher, Swami Chetanananda, who brought me here to Kathmandu, and to the Newar people themselves for sharing their work and knowledge so openly with me. My intention and hope is that in writing this article I am able to bring some awareness to the traditions that endure here in Nepal and the artists that have produced some of the most beautiful art this world has seen. © Karla Refojo 2006 |

| Footnotes: 1. With a few notes by Ian Alsop. 2. There have been a few studies of the modern Newar metal-sculpting

and casting tradition. See Ian Alsop and Jill Charlton, “Image

Casting in Oku Bahal” in Contributions to Nepalese Studies, Vol.

1, No. 1, 1973, available as a pdf file at: http://orion.lib.virginia.edu/thdl/texts/reprints/contributions/CNAS_01_01_02.pdf 3. The Newari word Jyapu is the name of the farmer caste, whose members are likely among the oldest inhabitants of the valley. Although there are several noted Jyapu metal sculptors, the majority of the metal sculptors of the valley are member of the high Buddhist Sakya caste, and are largely concentrated in two Buddhist communities in Patan, Oku Bahal and Nag Bahal. 4. The use of clay for the original sculpture, while customary in Western metal-casting traditions, is relatively rare in the religious sculpture of Nepal where the sculptors more frequently model the original image out of the same wax combination used for casting. 5. In the past the Newars generally cast their sacred images in almost pure copper, the best metal for fire gilding, which was almost always carried out after the casting and finishing. Indian metal sculpture traditions more commonly used variations on bronze (generically the term refers to any copper alloy, more specifically an alloy with tin predominant as the second metal after copper) or brass (where zinc is the second metal); often brasses and bronzes would have trace elements of the other metals of the pancha dhatu combination. 6. These are the chiselers, or “kotan kipin” of Patan; the “tap tap tap” of their tools can be heard in the roads and alleyways of Patan. 7. Oku Bahal, the most important community of Newar metal sculptors and related artisans. |