THE INVISIBLE ENVISIONED

Phantoms of Asia : contemporary awakens the past

A review article by Gary Gach

of the exhibition at:

The Asian Art Museum

200 Larkin Street, San Francisco, CA 94102, USA

May 18 - September 2, 2012

July 13, 2012

text and photos © asianart.com and the author except as where otherwise noted

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions)

One of the great, deep-water ports of the world, San Francisco is a natural gateway to a cosmopolitan diversity of people, goods, and views. Now its Asian Art Museum opens its first large-scale exhibition of contemporary Asian art. This renewal of vision is well-timed, given current, unprecedented global interest in Asian art. As always, the Asian delivers the goods in its distinctive, signature style.

Kasuga deer deity |

Bodhisattva |

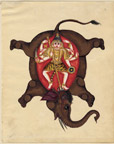

Dakini |

Seated Buddha |

Phantoms of Asia draws together 60 works by 31 artists from 15 nations. This, in turn, is all interlaced with 80 pieces from the museum's collection, many chosen from the vaults for this occasion. While in town, noted New York Times art critic Holland Cotter remarked it's an ingenious idea, one he intends to recommend when he gets back home, where the Whitney Museum is currently vacant. Indeed, whenever we consider past masters, we do so in the present, so they become contemporaries. This can lift a museum out of a stereotype as musty repository of a remote past, energizing it as a dwelling of vital vision.

Jay Xu |

Mami Kataoka |

Allison Harding |

Behind the scenes, the mastermind of this innovative convergence of vectors is Museum Director Jay Xu; the exhibition itself is brainchild of Mami Kataoka, and whose right-hand here is Allison Harding, the Museum's newly appointed curator of contemporary Asian art. And the event is drawing not only its core audience, but also new faces.

UntitledNormally, a colossal show takes many years to prepare -- fine for historical retrospects, but current tendencies and trends are ever in flux. So it's fitting for Phantoms to have been assembled in only 16 months. How she pulled it off remains a mystery, but then the supernatural pervades the show's subtext. And location plays a part here too: the Mori Art Museum, where she's curator, is up on the 53rd floor of a Tokyo skyscraper, informing her view with a sense of panorama and precision, plus perhaps giving her a feel for being part of a colossal beacon. Maybe too there's a bit of samurai in her family lineage.

Blending curatorial practice in with art practice, and serving it all up piping hot, she stirs us into the mix, as well. An ambience of personal participation, intuition, and spontaneity is freely at play here. Her grand-scale presentation provokes eternal questions. Where do we come from? Where are we going? What is the here and now?

"Despite a vastly changing political, economic, and social climate," Mami Kataoka asks, "do contemporary Asian art and culture find ways to connect to the past? In reaction to the limits of modernization, can we tap into the sensorial, the irrational, and the spiritual to broaden our understanding of the universe?"

The interrogatory mode serves as a basso continuo or “Zen koan” throughout her large-scale composition. Phantoms limns four, interrelated thematic elements:

- Asian cosmologies: Envisioning the invisible

- The World of the Afterworld: Living beyond living

- Myth, Ritual, & Meditation: Communing with deities

- Sacred Mountains: Encountering the gods

Mirror |

Bugaku dancers Handscroll |

Dohatsu Shoten |

Incense burner |

So "phantoms," because, as curator Kataoka told us: "... these objects may reawaken a deeply rooted receptivity to ancient, invisible forces that still surround us, yet, like phantoms, defy comprehension as to fixed forms."

Breathing FlowerAt the very outset, Phantoms of Asia

awakens the senses by engaging and energizing the literal space of the museum, inside and out. Across the street, Korean artist Choi Jeong Hwa has given Civic Center Plaza Breathing Flower, a 24-foot, candy-colored red lotus, its huge petals bouncing gently (by unseen motors) in the Pacific breeze. Made from recycled materials, it obliquely comments on globalism, while making a subtle linkage between art being av ailable from everyday materials, and enlightenment too. At my first viewing, early morning, I'd asked a random passerby what she'd thought, and, hair up in curlers, she replied its dancing made her feel like dancing; apt summary of a delicate but bold celebration of a populist, street-fair sensibility. A week after unveiling, it adorned the Asian Heritage Street Festival, celebrated by 90,000 people. San Francisco's multicultural daily life is 40% Asian American, another reason Phantoms is an idea whose time has come. And, in parallel festivities, a consortium of 16 Bay Area organizations joined flags to mount an Asian Contemporary Art Week.

Back inside, the lobby's been transformed by Korean-born, New York-based Sun K. Kwak. Her two- and three-dimensional calligraphy, Untying Space, traces the energy flows of the immediate I>chi (qi). Such a reading of geomancy -- popularized in the West recently thru feng shui -- is performative, as in the art of qi gong (chi kung) . And it prompts a consideration, to follow throughout the exhibition: How do artists treat space, and light?

Untying Space |

Calendars (2020-2096) |

Five Elements |

Heman Chong's Calendars fill all three walls of the Museum's activity room, as first interior space of Phantoms 1001 photos taken over the course of five years, it's an evolving diary of the future, in images, each of empty spaces yet to be filled, each given a specific, sequential date, in an imagined future. The lack of people evokes a sense of presence. As a meditation on absence, mortality, and timelessness, it invites us to empty our mind before receiving what's ahead.

Next door, an impeccable glimpse of the primordial awaits in the form of seven works from the Five Elements series by celebrated, New York-based photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto. In each, the traditional, symbolic shapes of the five elements are mounted atop each other, stupa-style: empty space (ç„¡, mu) crowns air, which rides atop water, flowing upon earth, resting atop a wooden column, on a metal base. Within each water sphere is a transparent photo of a seascape, evoking in this viewer a primordial longing for origin, as well as a sense of the fresh air and big mind of the open sea. While in San Francisco, Mr Sugimoto told us of his intention to mount 100 of these sculptures in his museum in Japan. As he put it, "they reawaken an awareness of the origins of consciousness in this present day."

Cosmological paintingEach pagoda of crystal sets against a blank screen of bright light. (Viewed carefully, the pyramid forms representing fire acquire prismatic sparks along the edges unintentionally?) The project might be likened to a spiritual aesthetic sushi, a concentration of long preparation resulting in profound nourishment to be savored. No stranger to the Asian Art Museum, or San Francisco, his presence here also serves as de facto elder statesman: he's in his 60's, while the curator and artists are all under 40; the youngest, 25.

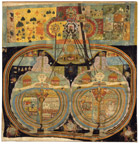

Entering the next suite of rooms, we're greeted by a large watercolor on cloth from Rajasthan (app. 1750-1850). Its complex mapping of our relationship with the cosmos, prompts more questions than answers (in tantric fashion?) -- as is the case throughout the exhibition.

AnonymityNearby, in Poklong Anading's ongoing Anonymity project, large-scale photos seem, at first glance to present people in everyday situations, but whose heads are orbs of light. (Haloes? And just where did that symbolic art practice originate, East or West?) On reading the wall text (essential, in a show such as this -- bringing the viewer to the artist, as well as vice-versa) -- we learn the anonymous people were posed holding a mirror in front of their head, reflecting the sun to the camera. Might this be a way of depicting original consciousness? Our imageless, True Nature? Our face before our mother or father were born ...

In an adjacent space, Palden Weinreb's abstract, simplified forms as new meditations on existence. On the opposite wall, hang awesome works of Guo Fengyui (1942-2010), mapping her own. These and other contemporary works face each other across a group of traditional devotional sculptures in the center of the gallery.

Jingming Point |

Shiva |

Astral Invert |

Mandala |

The ClassInside the exit of the second gallery, a Joseon dynasty king of Hell looks on as Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook offers a lecture (video) on death to sixteen corpses. The freedom of art enables her work to make death seem as light as a feather in the wind. Other artists working through questions of the afterworld include Ringo Bunoan, Jakkai Siributr and Takayuki Yamamoto.

What Kind of Hell Will We GoTakayuki Yamamato might be called "a children's artist" but not through art for so much as by kids; thus, genuine. For Phantoms, he makes his U.S. debut with What Kind of Hell Will We Go?, wherein he connected (through ArtSeed) with kids of age 7-11, from San Francisco's marginalized Bayview district. He showed them traditional Japanese mandalas depicting punishment and redemption. No one is perfect, he explained, so we all go to hell, then can cross over to heaven. He asked each student to create their own interpretation. Their artworks are installed on a wall of the Museum, as a mandala with a video in the center. They explain their realizations of their unique visions with disarming candor. Don't call people names, or you'll go to Name Hell, paved with mud and jelly and peanut butter: your feet will get stuck and you will die. Compare that to Stabbing Killing & Burning Hell, which is where you go if you use sharp things in the wrong way: when you go here you get stabbed in the chest, burned by fire, then eaten by sharks. Revenge & Stick Hell? Tiger Hell? Invisible Hospital Hell? You don't want to go there -- though the thought occurs to us that the children already have. (Like shamans, can children teach us ancient origins of contemporary creation?)

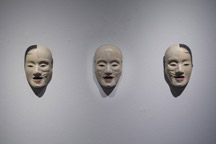

Over a dozen masks gaze out from Noh, Bugaku, Gagaku, and Tibetan contexts -- gateways to ghosts and demons. On an opposite wall, Motohiko Odani transforms the art of Noh carvings, in the SP Extra series, to reveal human flesh beneath the mask. (When someone calls you "a real person," do you think that's really an oxymoron? The word persona, refers to the mask used in Greek drama.)

Noh-Mask |

Malformed Noh-Mask Series |

Phantoms of Nabua |

Local ghost legends come alive in Phantoms of Nabua, a 10-minute video installation by Apichatpong Weersasethakul. In the 16-minute video The Class, another Thai artist, Aaraya Rasdjarmrearnsook, holds a seminar in front of a blackboard, lecturing to six corpses draped in white cloth, laying in metal pans. Her phenomenology on the topic of death is indeed a course we're all studying, and prompts good questions as well answers.

Geomantic InterventionAmerican artist Adrian Wong is a double threat in San Francisco right now, having been chosen for the Chinese Culture Center's the fifth annual one-person Xian Rui (fresh+sharp) artist. In that current installation, he documents his penchant for playing flaneur of invisible cities, with memoir composed in architectural palimpsests. For Phantoms he spent a year redesigning a quadrant of the Museum. His Geomantic Intervention invites viewers to feel for themselves the poetics of two adjoining spaces, without label: which has good and which bad feng shui? Ehipassiko. That sensibility also pervades Phantoms: art can inspire feeling, then invite us to fill in the rest.

Mt. AbundanceTraditional Chinese landscapes work on interior as well as external dimensions, curvy roads through deep valleys and lofty peaks, vast clouds above blanks seas below empty skies. Canadian Howie Tsui asks us to consider what if the landscape genre were composed of psychological images instead? Giving himself anchor images for composition, he improvises on silk scrolls, free-styling symbols sampled from Buddhist hell imagery, horror films, and comics. (Question: How is it that fear is acceptable in artistic culture but also acts as an index of social control?)

Phantoms shows us artists reflecting on mountains as connections between the human body, the landscape, and an invisible realm. When we first encountered Aki Kondo's mural of mountain spirits, we wondered why the word Guernica echoed in my mind. The answer came when we asked her about a certain group of forms, near the middle bottom, and she replied they were graves: Fukushima.

Mountain Gods |

BookHer singular contribution neighbors Chuanchu Lin's encounters with the literal humus of his life. In the organic unfolding of his mountains we heard an echo of Georgia O'Keefe's sincerity and truth. And an adjacent sculpture of Indra's descent down steps from heaven, rhymes with a terraced cliff of a mountain in monochrome oil. In a marvelous piece entitled Book: emerging from an open page, a cloud serves as pedestal for a scholar stone.

Scattered Deformities

in the End Fuyuko Matsui's work is right at home in the Japanese wing. A young master of Edo Nihonga, her phantoms are just that, and the scarier the better. As she layers sensory perception with invisible forces, so too does she render spatial and tonal contrast as well as line. We could only smile in wonder when, standing beside one of her pieces, she asked, aloud "Why is it that when we're depressed we sink, but ghosts, though burdened with passion, float?"

Another stand-out are the large painting and sculpture of Jagannath Panda, concurrently making his Ameerican debut at Frey Norris. Nearly nine-foot tall, the post-minimalist, cosmic noodling of Cult of Survival II, riffs off classical Indian painting, as hung nearby, but working in plastic pipe and auto paint, fabric and resin, faux snakeskin and plastic flowers, with impeccable flair for vision, detail, and execution. Head swallows tail as a pair of snails crawl slowly ...slowly. In a way, it crystallized for me the entire show's sweeping capturing and captivating of the essential, ephemeral poetry of life, in all its pliant durability.

The Cult of Survival II |

Hello! Another Me |

Jar with plum blossoms |

We're back in the lobby, after our initial tour. Unexpected resonances are reverberating in our mind -- such as how the work of both Sun K. Kwak and Hyon Gyon engage ripping of material. Going back upstairs, further discoveries include entire works, such as the landscaped inscapes of Bae Young Whan's Frozen Waves -- (What was he sensing / feeling / thinking as his brainwaves were recorded in hand-kneaded celadon?) -- and Terra Incognito, which turns the tables on the topology of introspection from another direction, via the grain of oak.

Frozen WavesMaybe we'd been silently hypnotized by the wall of Prabhavati Mappayil's exquisite, white, minimalist panels. On a smaller wall, alongside them, we only now discovered, way up, a hyper-real sculpture of a flower by Yoshihiro Suda. Elsewhere, a leaf of his, inserted like a chameleon into a glass case of an ancient figurine, seems to posit art as ... a smile! And, atop the third-floor escalator, I discovered on the bamboo, that's always there, the intricate calligraphy of Charwei Tsai upon the branches and leaves.

Absence of God VIISpace constraints preclude spotlighting all the artists. But, juxtaposed against all the traditional work on the third floor, (many with descriptive texts added for this show) there's but a single contemporary artist, and a genuine discovery: Kashmiri-born, London-based Raqib Shaw. His opulent, hybrid fantasies quote everything from Bosch to Mughal miniatures. Yet he sings in his own breathtaking voice, albeit as rendered in banal materials, with the meticulous precision of a porcupine quill -- confronting God ... and the gods.

Standing in the lobby one last time, before leaving the Museum for the day, we felt enlivened and even a bit enlightened. Phantom's striking, understated way of layering themes creates a conversation of artists across time as well as geography, inviting viewers to join in. And it felt like a far more effective presentation of spirituality in art, than countless other modern attempts, from Kandinsky on out -- prompting our own questions as to life, death, and our place in the universe.

Anno DominiWe need to see the physical to intuit the nomaterial. Such paradox isn't a contradiction. Spirituality extends beyond the six senses. And to be genuine, spirituality and art must always flower anew, fresh, out of the cultural soil of the present moment.

In so doing, Phantoms goes even further, in suggesting the interdependent, impermanent, empty nature of culture itself. For instance, Jompet's installation Anno Domini is a haunting testament to 's status as a post-colonial and post-industrial layering of range of sometimes seemingly conflicting subcultures. And that's but one episode in a panorama whose range extends from the Philippines to Persia, Indonesia to India. Plus, many of the artists grew up in multiple countries and now work across the globe. This begs the question as to how provisional (phantasmagorical?) is our concept of "Asia." (Why not also include Russia, Malaysia, Australasia?) And, redrawing the map, the exhibit also re-envisions time (The future meets the past in the present -- and vice-versa.)

As curator Kataoka told us, the aim is:

...to expand our imaginations beyond the present to a universal realm transcending space and time. .... By opening ourselves up to primordial sensibilities that lie dormant in the deepest layers of consciousness and memory, perhaps we can tap into the vast cosmological realms that extend far beyond everyday life.Site specific to the entire Asian Art Museum, Phantoms won't be travelling elsewhere. It is, however, accompanied by a fabulous, hard-cover, 352-page catalog, including interviews, transcripts, monographs, and 800 plates. [ISBN: 0939117592]

© 2012 Gary Gach