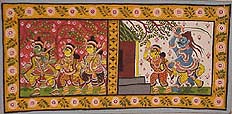

III. Themes that Illustrate Episodes from the EpicsStories from the medieval puranas (or epics), particularly the Bhagavata Purana, the Mahabharata, and the Ramayana constitute some of the subject matter of pata-chitras. Themes from the Vaishnava (that is, related to the worship of Vishnu) religion are common, including depictions of the rasa-lila, or Krishna's sport with the gopi maidens in the forest of Vraja (or Vrindavan) as well as depictions of Krishna's boyhood escapades, of Krishna slaying demons, etc. Rama and Lakshmana traveling in search of Sita, and Rama slaying Ravana, are popular themes taken from the Ramayana. 1. Episodes from the Bhagavata Purana The Srimad Bhagavata Purana (or sometimes, Mahapurana, great epic) is a medieval devotional text written from a Vaishnava point of view. It recounts many episodes from Hindu mythology in its twelve books. The most relevant of these books for devotees of Krishna is Book X, which describes the exploits of the young Krishna in the pastoral Vrindavan where he grew up. The book, especially the chapters on Krishna's youth, are a rich source of imagery for the chitrakaras. Three typical pata-chitras showing scenes from the early life of Krishna are illustrated and discussed here, as are several paintings that depict multiple scenes. The stories that accompany the illustrations are paraphrased from the Bhagavata translation by Goswami (1971).

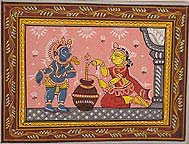

Figure 18 shows Krishna's foster mother Yashoda churning curds while the child Krishna looks on. The story is told in the Bhagavata, Book X, Discourse 9. The hungry baby Krishna went to his mother while she was churning curds just outside their house and she suckled him contentedly. However, she had put a kettle of milk on the boil, and when she heard it begin to overflow, she set the boy aside and ran into the kitchen. The child, annoyed, broke the pot of curds with a stone, and then went into the house, to the room where butter was kept in pots, and began to eat the butter. When Yashoda finished with the boiling milk, she went outside to find the broken pot. She then returned inside to find her son not only eating butter but also giving butter to a monkey. She grabbed a stick and chased after him. They ran round and round. Finally catching him, she set aside the stick (never intending to strike him) and tried to make him be still by tying him with a string—and then more string and more string. But no matter how much string she got, it always came out—because the Lord can never be bound—a little short. However, after a while, perceiving the frustration of his mother, Krishna submitted to being tied, thereby showing that the infinite and unmanifest Lord, out of love and compassion, allows himself to be controlled by his devotees. This picture shows the beginning of the incident from the Bhagavata. The pillar and the patio indicate the house. The baby Krishna (who typically is blue and wears a yellow cloth) stands by, with a crown on his head. The solid background of this picture is pink with filler designs. The pata-chitra has a double border; the outer border shows a vine and leaf design, the narrower inner border, a line of arcs or semicircles.

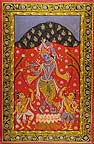

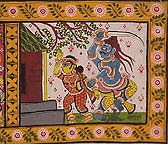

The incident is from the Bhagavata, Book 10, Discourse 25, verses 1-33. By way of introduction to the story, it should be mentioned that in the previous Discourse 24, Krishna advised his people of Vrindavan to desist in their worship of the God Indra; rather, they should worship the mountain Govardhana, the brahmans, and the cows. The villagers followed his advice. Indra, realizing that his worship on the part of the villagers of Vrindavan had been stopped, became exceedingly indignant. In his rage, he commanded the storm clouds to assault Vrindavan. This they did, and great volumes of water flooded the land. The cowherd people prayed to Sri Krishna to protect them from the anger of Indra. Krishna responded by uprooting Mount Govardhana from the ground with one hand. The villagers, along with their cattle and other possessions took shelter in the space beneath the mountain, and spent their time gazing on the Lord. Finally, after a week, Indra's pride was crushed and he called back the storms. Krishna told the people to return, and he set down the mountain in its proper place.

In the pata-chitra illustrated in Figure 19 (above), the artist shows Krishna lifting the mountain with one hand; indeed, with one finger, in an almost casual stance (see Figure 19a left). Two of the villagers, perhaps symbolizing the entire village, stand under the protecting mountain. The artist shows them gazing on Krishna, as described in the Bhagavata text. The outer border has a black background and its flowers are set within a spiral leaf pattern. The flowers which float in the red background of the picture are seven-petaled (rather than five-petaled as in other pata-chitras that employ this design element). This picture also has an additional color (besides the basic colors of the typical pata-chitra), the dark grey of the mountain. Brushstrokes in yellow, green, and white are meant to symbolize vegetation on the mountain. Otherwise, the picture contains the standard red background, double border with floral designs, and areas of flat color. The details on the clothing are well done. Sri Krishna stands on a lotus flower, drawn red-on-white, which itself is placed on a pedestal, treelike with trunk and stylized branches and leaves. The sky in this painting is clear, which, admittedly, is inconsistent with the story being illustrated. |