Tracing the History of a Mughal Album Page in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

by Laura E. Parodi,[1] Jennifer H. Porter,[2] Frank D. Preusser,[3] Yosi Pozeilov [4]

text and photos © asianart.com and the author except as where otherwise noted

March 08, 2010

Foreword The importance of scientific technical analysis in today’s professional museological practice cannot be overstated. While traditional connoisseurship remains a primary tool for the critical evaluation of a work of art, the eye of the modern curator can benefit greatly by the enhanced clarity of vision made possible by advanced analytical technology. This preliminary article not only presents the results of a recent major investigative study of a well-known Mughal album page, but also demonstrates the potential and a model for the interactive interpretation of data by art historical scholars and research scientists working in tandem. Stephen Markel, The Harry and Yvonne Lenart Curator and Department Head of South and Southeast Asian Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art |

This article presents recent research resulting from collaboration between the Conservation Center of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and Laura E. Parodi, a specialist of Mughal painting. It focuses on the recto of M.78.9.11, a Mughal album page whose image panel bears a date corresponding to 1591 CE [5] (figs. 1-2). On the basis of the suggestion that certain areas of the recto page may have been repainted, a technical examination focusing on the image panel was carried out which led to relevant findings.

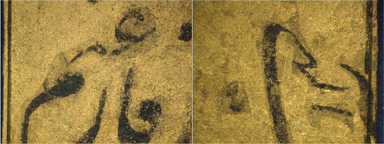

A complex sequence of successive interventions has been documented – including overpainting, enlargement and reframing – whose dates span a minimum of seventy years, from the mid-16th to the early 17th centuries. Certain iconographic features suggest some possible later restorations, but these will require further substantiation. Although the degree of complexity witnessed in M.78.9.11 will hardly prove typical, this type of analysis is likely to yield significant results when applied to similar works of art. As our research shows, the chronology of Mughal (and, more generally, Persianate) album pages cannot be assessed on the basis of visible evidence alone. This is further confirmed by a preliminary inquiry conducted on other Mughal pages in LACMA’s collection, which will be published in due course. The potential inherent in a combined technical-iconographic-stylistic analysis for the study of Persianate painting cannot be overestimated. Laura E. Parodi wishes to thank the Bruschettini Foundation for Islamic Art (Genoa, Italy) and the Khalili Research Centre for the Art and Material Culture of the Middle East (Oxford, UK) for contributing to support her research trips to examine this and other LACMA materials and to discuss the preliminary results of technical examination. Jennifer H. Porter thanks the Mellon Foundation for their financial support of her fellowship at LACMA. Initial examination by IR reflectography was facilitated by Elma O’Donoghue. FTIR and UV-vis spectroscopic analyses were facilitated by Charlotte Eng. The authors also wish to thank Sunil Sharma for his consultancy on the inscriptions. 3 Introduction: This report focuses on the image panel on the recto of M.78.9.11. At the outset of this study, it was known that the panel was a pastiche, a collage of multiple pieces of paper, though the number and placement of the pieces was not fully understood. Additionally, some discrepancies between the underdrawing and current composition had been noted but had not been investigated further. [6] Recent examination by Laura E. Parodi revealed certain iconographic inconsistencies and anachronisms, suggesting that the compositional changes might be more extensive than previously thought. Because repainting has been observed in numerous Mughal manuscripts, [7] it was decided to carry out a thorough technical-scientific investigation to better understand the construction and history of the piece. It was also decided to use only non-invasive techniques and avoid taking samples for analysis. As the research in this subject continues selective sampling may be considered in the future. It is our contention that the questions addressed in this preliminary report – which we hope to develop into a more detailed study in the future – are of broader relevance to our understanding of the dynamics of collection and reception of artifacts in the Eastern Islamic world and South Asia in the pre-modern era. For all these reasons, feedback on this preliminary report will be especially welcome. 4 Description, dating, and modern provenance of the painting: The page is decorated on both sides. While the verso is composed of a calligraphy panel with Chagatai poetry framed by a decorative scheme including portraits (fig. 2), the recto contains an image panel surrounded by a decorative floral frame (fig. 1). The image panel on the recto side, which constitutes the focus of this research, presents itself to the naked eye as consisting of one main composition, which was placed close to the border on the right-hand side and extended at the top, left and bottom. The joins of different pieces of paper are clearly visible. Together, the main composition and extensions show a group of riders in a landscape, accompanied by some other figures; these include a man with a rifle (whom we shall name the ‘hunter’) (fig. 13) at the bottom, a ‘scout’ who precedes the riders and a man busy carrying wood at the extreme right. Since the poetry inset at the top mentions a king setting out on a hunt, the composition has become known as ‘Hunters in a Forest.’ The image panel also contains a number of gilded calligraphy insets, but a detailed study of their inscriptions was beyond the scope of this report. However, they will be briefly mentioned insofar as they are relevant to a preliminary understanding of chronology and attribution. There is no reason to doubt the authenticity of the inscription located at the extreme right of the bottom center panel, first published by Basil Robinson and further discussed by Milo Beach (1978: 46) which gives the artist’s name: “‘amal-i murīd dar chahār martaba-i ikhlās pāy bar jā Sharīf” (work of the disciple in the four stages of sincerity, with foot in place, Sharif) [8] (fig. 3). An additional inscription also noted by prior scholarship, located in the leftmost portion of the same panel, gives the date as “9 Farwardīn 999 in Akbar’s thirty-sixth regnal year. This is equivalent to March 20, 1591, so that this painting [...] appears to have been executed in conjunction with the celebration of nawrūz” (Soucek 1987: 171) (fig. 4). According to Som Prakash Verma (1994: 299), Muhammad Sharif – an artist active under Akbar (r. 1556-1605 CE) and Jahangir (r. 1605-27 CE) – was the son of Khwaja ‘Abd al-Samad, one of the masters whom the second Mughal ruler Humayun (r. 1530-1556 CE, with interruptions) first met in Tabriz in 1543 CE and summoned to his court in Kabul ca. 1549-50 CE. [9] Various authors have expressed perplexity as to Sharif’s authorship of the image panel, despite the signature: see especially Beach (1978: 46), who notes that “The flattened space, the absence of convincingly portrait like characterizations, and the interest in decorative and minute detail, are all typically Iranian traits; while the dark tonalities and the densely packed mountain forms, together with the heavy outlining, point to ‘Abd al-Samad’s authorship.” For this reason, he proposed to consider the painting a joint work by ‘Abd al-Samad and Sharif. Other scholars have generally agreed with this suggestion, which our research now allows us to refine considerably.

However, extensions of the image panel along the upper, lower and left edges (including the rider holding a bow and arrows (fig. 10-11) and the hunter (fig. 13-14)) are certainly datable to a later phase, which scholarship traditionally assigns to the first two decades of the 17th century; other interventions may have occurred a decade or two later, under Shah Jahan (r. 1627-57 CE). As pointed out in previous scholarship, the overall size of the folio and its borders on the recto and verso conclusively indicate that it was once integrated into the now dispersed ‘Gulshan Album’. [10] As Milo Beach (2004: 117) has intriguingly suggested on the basis of a date found in one of the margins (1008 H / 1599 CE), the early stages for the assemblage of the Gulshan may have begun as early as Prince Salim’s court at Allahabad (ca. 1600-1604 CE). In a prior contribution, Beach (1978: 46) more specifically observed that “The verso margins [of the LACMA folio, fig. 2] contain some of the most sensitive of Mughal portraits and can be attributed to Govardhan [a leading artist in Jahangir’s workshop after his accession] on the basis of signed border figures dated 1609 in the Berlin muraqqa‘”. He (1978:46) and Pal (1993: 219) consequently date the folio overall to ca. 1610 CE, a few years after Salim’s accession as Emperor Jahangir in 1605. The documented modern provenance of M.78.9.11 can be traced back to 1966, when it was published in the catalogue of an exhibition organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Arts of India and Nepal: The Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection (Beach 1966: 143-144, no. 198). Subsequently, the album page was included in a group of primarily South Asian and Himalayan objects purchased from Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1969. However, due to the payment for the collection being spread out over a number of years, the LACMA folio was not formally accessioned until 1978. [11] 5 Technical Examination and Analyses: The page was photographed under incident, raking, and transmitted light. UV-reflectance and UV fluorescence and IR-reflectance images were taken and the page was X-rayed (figs. 5-7). The page was then examined under a stereo-microscope (5-40X magnification) and a digital microscope (5-175X magnification) and photo-micrographs were taken. To identify the pigments the different colors were analyzed by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF). The painting was also analyzed using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) reflectance spectroscopy and ultraviolet-visible reflectance spectroscopy (UV-vis). Details about the equipment and conditions can be found in the appendix. The interpretation of the XRF data, X-radiographs, IR photographs, and transmitted light photographs was complicated by the images on the verso of the page. It was therefore necessary to closely consult images of the verso when attempting to interpret these data (fig. 2). Most of the pigments and materials which could be identified by the available non-invasive methods were wholly consistent with the dating of the composition on the recto side. These include gold, lead white, red lead, ultramarine, copper green (possibly copper blue), iron oxide red (red ocher), and orpiment. As has been shown in numerous previous studies, all of these pigments have been in use throughout the region and throughout the history of the page, and therefore could not provide any historical or chronological information for our study. [12] Only the presence of small amounts of zinc white, a pigment which was not in use until the 18th century, signaled some later restoration, [13] which probably did not involve iconographic changes. 5.2 Structure and manufacture

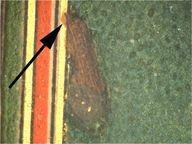

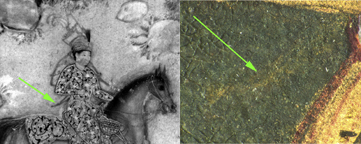

The image panel is made up of at least four separate pieces of paper, the joins of which are clearly visible in the X-radiograph, micrographs, IR-reflectography and visible light transmission photographs (figs. 5-7). The four pieces are set within the larger frame of the decorative page border. Within the image panel, three distinct zones of painting appear to overlie these pieces. We shall refer to them as: the outer and lower borders (comprising the extensions), the inner border and, finally, the central panel (fig. 8). Though the outer and lower borders (which include the calligraphic inscriptions at the top and bottom of the page) were applied on separate substrates, they appear to be directly related and probably contemporaneous. A single campaign of painting appears to have been applied directly to the paper in these areas (fig. 9). While some variations between visible paint layers and underdrawings can be seen (figs. 10-11), the paint layer is smooth and undisturbed (fig. 12). This appears to be the final paint layer applied to the overall image, and it seems to have also been applied in other sections as a means of unifying the composition.

Previous scholars have dated the extensions – more specifically comprising the leftmost rider (fig. 10) and the hunter at the bottom (fig. 13) – to the early 17th century. Beach (2004: 117) more specifically proposes to attribute the rider to the youthful Abu’l Hasan. This was the son of Aqa Riza, the master who, according to his reconstruction, would seem to have supervised the early stages of the Gulshan Album in the workshop of Prince Salim in Allahabad. An attribution of the extensions to the patronage of Salim / Jahangir – whether before or after accession – is only logical, given that he was the initiator and patron of most of the Gulshan (also known in the past as ‘Jahangir’s Album’, although more recent scholarship ascribes part of it to Shah Jahan).

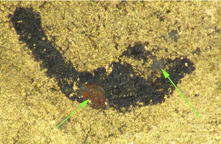

In favor of a dating of both the rider (fig. 10) and hunter (fig. 13) to a single phase of reworking is the similarly smooth surface. Some of the palette also recurs – note in particular the rich, luminous light blue of the rider’s dagger and hunter’s rifle. However, some stylistic as well as iconographic discrepancies may be noted, which demand an explanation. To begin with, the rider and hunter are very different in terms of modeling and facial features: the hunter’s dress presents none of the remarkable (and indeed unusual) ‘stippled’ shading seen on the rider. While the rider himself seems to wear slippers (hardly suited to a hunting or riding expedition), the hunter, although dismounted, wears boots complete with spurs. At its most basic, this may result from reliance on different models – or in other words, signal the use of stencils (tarh), a practice that is well documented in the Mughal workshop, yet largely unexplored in its full implications. The underdrawing yields further clues in support of this possibility. The silhouette of the rider (fig. 11) [14] seems indeed to have been reproduced from a model: note the thick outline of the torso and head, which encompasses the profile of the turban but does not indicate its folds. And indeed, the rider seems to be a virtually exact mirror replica of the youth in a page from a Diwān of Hafiz illustrated early in Jahangir’s reign. [15] The rather unusual, contrasted palette [16] and details of dress are very close – with the yellow being transferred to the saddle in the case of the LACMA rider. Similarities would seem to go as far as reproducing the slippers worn by the Hafiz youth – hardly acceptable as part of a rider’s attire. Some other details seem to signal that the painter responsible for creating the LACMA rider was not concerned with reproducing the precise details of dress: the half-open jāma of the Chester Beatty example is replaced in the LACMA page by ‘wavy ribbons’. This detail, along with the transversally striped trousers, seems to constitute a possible deviation from the norm. [17] By contrast, the hunter (though probably not his rifle) was drawn with a free hand, as is shown by several pentimenti (fig. 13-14). The details of his facial features correspond fairly closely with those of works securely ascribed to Jahangir’s patronage. [18] In the future, more detailed comparisons may potentially lead to precise attribution. The rider, for its part, remains somewhat more problematic. As we have pointed out, several of its stylistic or iconographic details deviate from the standard of early 17th-century Mughal painting. We have cited the ‘stippled shading’, the slippers, and two details of dress. To this we should add a more specific iconographic feature: the brown horse’s plaited mane (fig. 15).

This feature, which is most closely associated with Mughal (and provincial) portraits of the 18th century, [19] seems to make its earliest appearance sometime during the 17th. This is testified for instance by ‘Prince Awrangzeb facing a maddened elephant’ in the Windsor Pādshāhnāma. [20] However, it has proved difficult to identify the feature in paintings produced for Jahangir, while at least one instance where the horse’s mane is unplaited may be cited [21]. A curious finding in the course of this research has been that by the early 17th century, the direction of riders – particularly imperial riders – is virtually invariably from right to left. [22] The mane seems to have been quite consistently combed to the right side of the horse’s neck; it is accordingly hidden from view in the vast majority of cases. The LACMA riders and Awrangzeb in the Pādshāhnāma illustration are among the rare exceptions. Combined with the general scarcity of depictions of Jahangir riding, this has prevented us from identifying a suitable parallel so far. Suggestions are welcome. In any case, if a later date for this feature is confirmed, our reconstruction of the chronology would have to be modified accordingly.

An additional feature that deserves mention in this area is the sky. The Persianate gold sky of Sharif’s composition was extended at the top using bright orange stripes, perhaps suggestive of clouds, and distant flocks of birds. Again, based on preliminary inquiry, it would not seem easy to reconcile this feature with an early 17th-century date – although it is by no means a diagnostic feature. Preliminary research seems to associate the orange glow more specifically, or at least more consistently, with the latter part of Shah Jahan’s reign. The feature then seems, once more, to gain increasing popularity in the 18th century. In the LACMA page, this may either indicate successive overpainting, or signal greater continuity between different phases of the Mughal school than is commonly assumed – a topic worthy of further consideration. For their part, flocks of birds in the distance would seem to be introduced in Mughal painting already under Akbar. [23] The orange skies and flocks of birds seem to have been combined consistently from the 18th century onwards, but there is no reason to rule out an earlier date for this treatment of the sky in the LACMA page at our current state of research. Since no specific literature is available on the subject, a more adequate contextualization will require the examination of a larger number of works than it has been possible to include for the purposes of this report. Finally, it may be noted that a hind foot of the brown horse is partly painted over the Gulshan border (fig. 16). While in itself not a conclusive piece of evidence for a significantly later dating of the outer border, this represents at least an index of relative chronology.

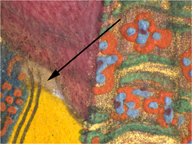

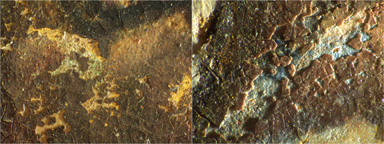

One of the most striking discoveries made in the course of this study was that the current composition of the area we have labeled the ‘inner border’ overlies a painted floral manuscript page border. This is best evidenced by IR photography (fig. 17) as well as by observations under the microscope. Gilding and pigmented areas can be seen through the uppermost paint layer, and in some areas orange and black flowers on a greenish-blue ground can be distinguished (figs. 18-19). A pattern of ample scrolls terminating in lotuses and other smaller flowers, outlined in gold on a pale greenish-blue background, can be made out (figs. 20-22). As may be seen, the bottom portion of the border is missing, but the other three sides are preserved, and consistently measure 2.7 cm in width.

The border, as we shall see in further detail below, frames an earlier composition, which was incorporated by Sharif into his own. This discovery opens up an unexpected scenario: if the page was preserved complete with its border – albeit partly missing – why would it have been incorporated into a later work? Some possible answers will be proposed below.

The uppermost paint layer in the area corresponding to the floral border exhibits very poor adhesion to the underlying layer, which has resulted in extensive flaking (fig. 23) and appears to have attracted numerous repairs and modifications over time. In particular, the faces of figures in this area have been reworked, perhaps multiple times (fig. 24-27), resulting in their overall rough appearance.

The iconography and style of the uppermost paint layer in this section is consistent with an attribution to the imperial Mughal workshop in the late 16th century, earlier discussed by Pal (1993: 219-220): these portions of the image panel, in other words, must belong to Sharif’s composition. For instance, the heads and necks of the horses in the inner border section are not rendered according to the same conventions as that of the brown horse in the outer border, discussed above (figs. 28-31). The clothes worn by the figures in this area are also fully consistent with a dating to Akbar’s reign. Nonetheless, overpainting did occur in the inner border area in conjunction with the extension of the composition, most likely in an attempt to repair the painted layer and to unify Sharif’s composition with the later additions.

However, for the moment it is only on the basis of their iconographic features that two of the three horses in the group to the left, along with their riders, can be securely assigned to Sharif’s composition. No material evidence was found which conclusively distinguishes between the painting in the inner and outer borders. The difference in the appearance of the front and back parts of the red horse in UV fluorescence image (fig. 32-33) may be due to a difference in painting materials used in the two borders and therefore distinct painting campaigns; however, like the figures in the inner border discussed earlier, the front of the horse has undergone one or more restoration treatments, possibly involving overpainting and/or the application of a coating (fig. 34), and it remains possible that the difference in fluorescence is due to those overlying restorations, rather than the original paint below. From a materials point of view therefore the sequence of painting in this area remains ambiguous: it remains possible either that the inner and outer borders were painted contemporaneously (i.e. 17th century), or that the inner border was painted earlier and then integrated into the outer border scheme.

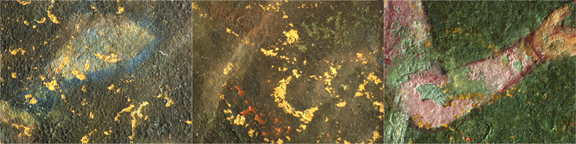

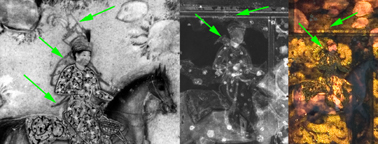

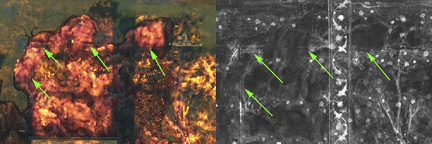

5.2.3 Central panel: IR-reflectography, X-radiography, and photography under transmitted light have evidenced an earlier painting in the central panel (or possibly a tinted drawing, as we will discuss in further detail below) underneath the current composition (fig. 35-37). The most notable detail is the presence of an earlier, clearly distinguishable and datable rider under the current central figure (fig. 35). This figure was first clearly seen in IR images, and traces of its paint were found during microscopic examination (fig. 40-41). An earlier paint layer also underlies the mountainous landscape surrounding this figure (fig. 42-43), but the nature and composition of this layer were less easy to deduce, since its outlines cannot be distinguished.

On the basis of iconography, which will be discussed more fully below, the rider underlying the central figure can be securely ascribed to the workshop of Humayun ca. 1550 CE: we shall therefore refer to this figure and the compositional elements associated with it as “the mid-16th-century composition”. This is the earliest layer evidenced in M.78.9.11. The discovery of a mid-16th-century composition from the scantily documented early Mughal workshop – possibly preserved along with its contemporaneous border – may well be the most significant outcome of our research. Traces of the figure can be seen in the light transmission photograph and X-radiograph (figs. 36 and 37). Disturbances in the texture of the green background surrounding the figure can be seen in raking light (fig. 38), and the UV image suggest that a second green paint layer was used to blot out traces of the original figure where the new figure did not cover it completely (fig. 39). A careful examination of the rider’s figure has yielded no clear indication of the nature of the original paint layer.

Traces of gold paint are found in the area of the headgear, cloud-collar, dagger and arm (fig. 40-41). X-radiographs and transmission photos provide no further information. The diffuseness of these vestigial paint layers as compared to the clear outlines seen in IR may suggest that the original figure was fully painted, then either scraped or otherwise removed before the new figure was inserted into the original background of the central panel, leaving only the preparatory drawings visible. It is also possible that the composition may have been a tinted drawing, enhanced with touches of watercolor and gold, or that it was unfinished. Further information regarding the technique can only be obtained through sampling and study of cross-sections, while some external evidence in support of a reconstruction of the mid-16th-century work is discussed below. Though they may appear identical initially, microscopic comparison of the green background paints used in the outer and inner borders and central panel shows that the outer border layer is intact and solid, while the green of the central panel shows a distinct crack pattern and has a very different appearance under UV illumination. This earlier green would therefore seem to belong to the mid-16th century composition, while the green background of both the inner and outer borders appears distinct and designed to replicate and extend this earlier background. Various greens are visible throughout the central panel and while XRF, FTIR and UV-vis spectroscopy suggested some differences in their composition, it remained difficult to assign them to distinct painting phases or relate them to painting in the inner and outer borders.

The composition of the painting underlying the mountainous landscape is less easy to discern. The number of underlying paint layers is unclear as well; therefore it is difficult to determine which details may have been contemporaneous with the central figure. The underlying layer seems to have been almost completely obliterated by the uppermost painting, often resulting in very rough paint textures in the upper paint layer. There is little indication of the nature of the earlier composition, and therefore it cannot be definitely related to the overlying composition. Gilding and blue and green paint underlie much of the mountainous area (fig. 42-43). Some smaller islands of earlier paint appear to have been left exposed, surrounded by the later paint layers, and some details suggest that the later paint layer may replicate some of the composition of the earlier painting. Note in particular some branches which emerge from under the currently visible tree, and do not exactly coincide with them (fig. 44). These survivals suggest that the earlier painting depicted a landscape containing details such as leafy trees and rocks. Interestingly, the upper edge of the central panel follows the contours of the mountains, which extend beyond the edge of the straight border line, with the result that the paper of the central panel overlaps onto the paper of the floral border here. In addition, a ruling can be seen beneath the mountaintops in the transmission and IR photos and in the X-radiograph (figs. 45-46). Since the spliced portion of the central panel is cut out along the outline of the current mountains (fig. 47-48), a mountainous composition certainly existed before the central panel was inserted into the floral frame. The painting may have been executed first, then mounted into one of several identical frames that were to constitute the structure of the original manuscript (more about this below), and finally a suitable border decoration was provided, as with other individual pages; this would be consistent with our current understanding of workshop practice. Overlapping compositions are quite common in Timurid or Safavid painting, and although unusual in a work of the Mughal school, may still have been fashionable in Humayun’s time.

A secure terminus ante quem of 1591 CE for the dating of the underlying composition, as well as the border, is given by the date of Sharif’s work. A more precise dating to the reign of Humayun (that is, no later than 1556 CE) is strongly suggested by the iconography and style of the composition. But it remains possible that the mid-16th-century painting was separately set into the floral border at some date after its creation (for example, as with other unfinished paintings, for inclusion in an album), and the two parts (panel and border) then joined and integrated by heavy overpainting. If this were the case, the floral border would date to sometime between ca. 1555 and 1590 CE. Only further study with cross-sections will help to further clarify the relationship between the central panel and inner border in this regard.

An attribution of the mid-16th-century painting to the workshop of Humayun is corroborated by strong iconographic evidence: the rider – a young prince aged about ten or twelve – wears an accurately rendered Tāj-i ‘Izzat, the headgear reserved for Humayun’s close associates [24] (fig. 40). A close iconographic parallel for it is provided by the image panel in an album page now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, [25] although the PMA rider is younger and wears a less elaborate Tāj. It is also much larger in relation to the page and is painted against an almost blank ground relieved by flowery plants. By contrast, the rider in M.78.9.11 is part of a more elaborate composition. The two paintings would not seem to be by the same hand either, since the Tāj is rendered according to different conventions. On a side note, it is interesting how the proportions of the rider to its mount – typical of both these early Mughal paintings and reflecting Central Asian conventions – were altered by Sharif to reflect those familiar to him and his Hindustani audience. While a more detailed discussion of the dating and attribution of the mid-16th-century composition is best reserved for a future article, it may be observed that the PMA and LACMA paintings may well depict the same individual at two different ages, with a parallel development in his gold-brocaded Tāj: note in particular how in M.78.9.11 this is embellished by a double plume and a delicate bejeweled chain (fig. 40). The suggestion is especially interesting when we consider that the PMA example has been plausibly interpreted by John Seyller as a portrait of the future emperor Akbar in childhood, as the young rider holds a safīna (a small, portable poetry album) inscribed with the words “May the world grant you success and the celestial sphere befriend you. May the world-creator protect and preserve you”. [26] Assuming this interpretation is correct, Akbar’s age in the PMA specimen (some eight or nine years) would agree well with a dating to ca. 1550-51 CE, while a dating to ca. 1554-55 CE could be proposed for the rider in M.78.9.11. By way of historical contextualization, it may be said that in 1551 CE, following the death of Humayun’s brother Hindal, Akbar received all the latter’s appanage and practically took up his uncle’s place in the court’s hierarchy, [27] while by 1554-55 CE – despite his young age by modern standards – Akbar was already reaping his first military successes during the campaign to reconquer Hindustan. As mentioned, the Tāj was a hallmark of honor reserved for Humayun’s close followers (known as ichkiyān, or intimates). It came in a complex hierarchy of increasing splendor, from a plain qalpaq similar to the one still worn by Kyrgyz pastorals today to the richly brocaded version embellished with a scarf and several ornaments, including feathered pins (jigha, sarpīch) that was reserved for the ruler. An impression of the full range of forms may be gained from a painting, now in Berlin but at one time also incorporated into the Gulshan; the work is ascribed to the artist Mulla Dust in Kabul sometime after 1546 CE. [28] The ostrich feathers which decorate the Tāj in M.78.9.11 and the gold brocade of its fabric strongly support an identification of the young rider with the heir-apparent Akbar. In early Safavid as well as Humayuni painting, ostrich-feather ornaments would seem to be reserved for princes of the blood, for their arms-bearers (perpetuating the tradition of the Chingizid keshīg – the legendary imperial Mongol bodyguard) or, at most, for great epic heroes such as Rustam. [29] Judging from works of both schools, gold brocade – seen in the PMA specimen and still detectable in the LACMA page – seems to be an exclusive royal prerogative, used only on special occasions.[30] It is also worth noting that, although several retrospective images of Akbar wearing a Tāj exist, [31] the style of the LACMA image is unmistakably Humayuni: the general shape of the headgear, the ostrich-feather sarpīch and the minute flower-shaped ornaments of the chain attached to it have very close parallels in securely attributed works from the Kabul workshop under Humayun. [32] Some historical background may be added: Humayun regained the throne of Kabul from his brother Kamran in 1545 CE, then lost it and captured it once more in 1549 CE. In a letter to the Khan of Kashgar in 1550 CE, preserved in a slightly later source, Humayun praises the skills of the artists in his employ and mentions a few. [33] An association with surviving works has only been established for some of them – the masters trained in the Safavid workshop of Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524-50 CE), one of whom was Sharif’s father, ‘Abd al-Samad. Despite the current fragmentary state of the rider’s figure, the overwhelming importance of the setting would indeed support an attribution to ‘Abd al-Samad. [34] The attribution in turn may contribute to explain how this page was incorporated into Sharif’s composition – despite the awkwardness resulting from the presence of a border – and to clarify why the ensuing style is at variance with that of his known works. The issue is discussed in greater detail below. While the large calligraphy panels which span the upper and lower portions of the page are clearly contemporary with the outer and lower borders (and we shall not consider them in this discussion), the two calligraphy panels found within Sharif’s composition (one of them partly encroaching onto the inner border) are certainly earlier, though their exact dating and history is fairly complex to unravel. Both panels appear to have been painted directly onto the inner border and central panel, and not onto separate pieces of paper as was previously hypothesized (cf. Pal 1993: 220). In other words, the inscriptions were penned directly onto the paper substrate: no disparate paint layers underlie them, with the sole exception of the left half of the bottom panel, which partly overlaps the floral border. This too, however, is not applied on a separate paper layer but just over the existing paint layer. It appears therefore that panels were foreseen in the original, mid-16th-century composition. This implies that the Humayuni composition was conceived as part of an illustrated manuscript, not as an independent work or an album folio. Remarkably, the ‘appendix’ at the extreme right of the bottom panel, providing Sharif’s signature, is not pasted over a painted layer. We must therefore presume that provision for it was made in the mid-16th century composition, or, alternatively, that this area was blank at the time when the inscription was penned.

From a structural point of view, it is currently impossible to tell whether any of the text panels were inscribed or left blank in the mid-16th century phase – although, as testified by the example just cited, some hypotheses can be made on the basis of the textual content. The iconography may also be called in support (see below). On the other hand, as mentioned, the left edge of the lower calligraphy panel, where it overlaps onto the inner border, is painted onto the floral border (fig. 49). The lower panel was therefore extended when the painting was reworked. This was done, we may infer, in order to accommodate the inscription giving the date of Sharif’s composition. The edges of both text panels were then slightly enlarged and enhanced with blue and black borderlines at some later point, probably at the same time that the image panel was integrated into the upper and lower borders (early 17th century). Additionally, a decorative panel with floral scrolls was inserted into the lower panel at this time. Since this addition would seem to have significantly altered the layout of the lower panel, the inscription may have been changed at this time also.

Evidence was indeed found that the inscriptions of both panels have been reworked to some degree, at least once. Various layers of black and gold paint were observed in both calligraphy panels, following the lines of the inscription (fig. 50-51). However, this could simply be due to a refreshing of the old inscription, a practice which has been noted in the course of this inquiry in other Mughal illuminations in the LACMA collection. Though no direct evidence of conflicting inscriptions was seen, these might be very difficult to detect through the non-invasive means employed: IR often cannot penetrate gilded layers to reveal conflicting paint layers beneath, and the complexity of X-radiographs and transmission images prevented the extraction of any further information from these sources. Further understanding of these areas will require study with cross-sections. While some of the later modifications may only have updated or refreshed details of the inscriptions, other elements were certainly embellished. The extent of modifications to the overall central panel and inner borders at the time of the creation of the outer and lower borders must therefore be carefully considered. If this situation were confirmed in the future, it would not be too far-fetched to hypothesize that the mid-16th-century Humayuni manuscript page never received its foreseen text. This has important implications on our reconstruction of the early history of the image panel. There are other instances of unfinished pages which made their way into albums, both Persian and Mughal, but it is of no small consequence to suggest that a folio datable to the reign of Humayun is from an illustrated manuscript, rather than an individual work. Only one complete manuscript and one individual painting purportedly from an illustrated manuscript have so far been associated with the Kabul workshop under Humayun (see below). Our suggestion is especially daring when we consider that no contemporary historical source was commissioned by Humayun in the latter part of his reign: how to reconcile this with our identification of the main figure as Prince Akbar? As Francis Richard (1994) has shown with his attribution of a copy of Nizami’s Khamsa to the Kabul workshop under Humayun, it is equally possible for the protagonist of a literary work to have been cast in contemporary garb – when not actually identified with a contemporary figure. This was also common practice at the contemporary Safavid court: witness for example the copies of the Shāhnāma and the Khamsa illustrated for Tahmasp, where some of the just rulers of the past closely resemble the patron. [35] Our composition does have a certain Shāhnāma flavor: it brings to mind images of Sam traveling to the Simurgh’s aerie – but Sam is an unlikely parallel for Prince Akbar. A preliminary survey of published Timurid and Safavid illustrations from the said literary works has not yielded a close comparison. The only iconographic parallel from Tahmasp’s Shāhnāma – although resolved with a very different composition – is ‘Bahram Gur advances by stealth against the Khaqan’ (Dickson & Welch 1978, II: no. 232), where several attendants follow a lavishly-dressed ruler, carrying arms in their casings. Interestingly, according to Richard’s reconstruction (1994: fig. VIII), it is Bahram Gur that is depicted as Akbar in the Paris Khamsa. A remarkably poignant piece of evidence may be brought in support of the hypothesis that the mid-16th-century composition was originally ‘Abd al-Samad’s contribution to a Shāhnāma commissioned by Humayun. Just few years ago, the late Stuart Cary Welch (2004) published a small Shāhnāma illustration, which he attributed to Mir Sayyid ‘Ali – the other great Safavid master that joined Humayun in Kabul. The painting, depicting ‘Zal in the Simurgh’s nest’ (unconventionally located atop a tall plane tree rather than the customary mountaintop), appeared tiny – Welch gives its size as 5 7/8 by 3 15/16 inches – but extremely well crafted (Welch 2004: fig. 1). Of no small relevance to our purposes is the technique in which the painting published by Welch is executed: a combination of fully painted areas (tree foliage), gold (sky) and delicate washes. Of even greater relevance to our purposes is the painting’s size: its width corresponds virtually exactly to the mid-16th-century composition in the LACMA folio. The page published by Welch is shorter, but it is preserved in a thin floral border that Welch himself (2004: note 1) ascribed to a later, probably 18th century, date. Equally interestingly, Welch went through some effort to justify the choice of locating Zal and the Simurgh so close to the upper border. Could this not result from resizing? The mid-16th-century composition in the LACMA folio has rather elongated proportions – 18 x 10 cm, that is, nearly 2:1. It is not difficult to imagine the plane tree of ‘Zal in the Simurgh’s nest’ extending further upwards, and possibly splicing into the upper border in a manner similar to the mountains in the LACMA composition. In addition, the page published by Welch may have comprised a text panel (possibly unfinished) which was not appreciated at the time of the later reframing and was accordingly excised, resizing the image in the process. If our reconstruction is correct, we would be looking at the first two documented fragments of a Shāhnāma commissioned by Humayun in Kabul around 1550 CE, when the two Safavid masters first joined him in Kabul, and possibly unfinished at the time of his death in 1556 CE. The LACMA specimen might even be preserved in its original border – giving us a sense of the size and appearance of the actual manuscript as well as providing glimpses into workshop practice in the early Mughal period. This discovery may lead to the emergence of more fragments from the same work. While a detailed study of the textual contents – ideally, combined with cross-sections in order to shed light on their chronology – is best reserved for the future, it is possible to make a few suggestions based on currently available evidence. In this respect, it must be pointed out that the current text panels do not suggest a connection with the Shāhnāma or, for that matter, with one of the Khamsas (Nizami’s or Amir Khusraw’s). Whether this indicates that the Humayuni page never received its planned text, or whether the text was altered at a later date, is impossible to say at this stage. But whichever the case, the current verses cannot belong to the original composition if we accept the painting to have come from a Shāhnāma, and must therefore have been added at the time of Sharif’s re-creation of the scene.

6 Discussion It remains to be explained how a manuscript page of ca. 1550-55 CE, complete with border (although possibly with empty inscription panels), ended up being incorporated into a later painting (rather than being remargined, refurbished or preserved in its pristine state). Sharif’s decision to use the composition to produce a pleasing and somewhat archaic-looking artifact will not appear too far-fetched if we assume his father to be the author of the original painting. Priscilla Soucek (1987: 170-171) has noted how the two known signed works by ‘Abd al-Samad contain inscriptions that establish a connection with the Nawroz. In addition, the LACMA page is usually considered to have once been paired in the Gulshan with a page containing another painting by ‘Abd al-Samad, dated 998 H / 1587-88 CE, which depicts ‘Jamshid writing on a Rock’. [36] This suggestion is further discussed below. For the present purposes, it is interesting to note Soucek’s suggestion (1987: 171) that the Jamshid painting may also have been executed on the occasion of a Nawroz – its subject, Jamshid, being credited with the institution of the feast. Sharif’s composition would therefore seem to pursue a tradition of presentation pictures connected with this feast established at the Mughal court under Humayun. That Sharif and his father were not the only artists involved is testified indirectly by the cited Berlin picture showing Humayun and his retinue in the hills – whose Nawroz connections, even in the absence of an inscription, seem strong. [37] Interestingly, such pictures seem to have been systematically collected in the Gulshan. [38] Presentation pictures, one could well argue, involved a dimension of novelty or rarity – particularly when associated with the feast of the New Year. Proof be that in two instances (previously discussed by Soucek 1987: 170), ‘Abd al-Samad’s dexterity in execution is stressed, by stating they were completed in half a day. This could hardly have been the case with the Berlin painting – a large and meticulously crafted work with countless grotesques and other tiny details requiring painstaking recollection, doubtlessly aimed at delighting the intellect as well as the eye of the recipient. But either way, the exceptionality of the feat seems to be the point, along with the special relationship established between the giver and the recipient. Accordingly, one possibility is that Sharif came across the Humayuni-period work in his father’s household and decided to turn it into a present for Akbar. ‘Abd al-Samad was still alive at the time, and may have himself suggested this possibility. Alternatively, Akbar or Salim may have come in possession of the unfinished or damaged copy of Humayun’s Shāhnāma and commissioned the painter to come up with something special for the Nawroz. Perhaps a more refined version of this explanation may be proposed on the basis of iconography. Although a detailed discussion of subsidiary figures cannot be provided at this stage, there is some suspicion that the scene painted by Sharif did not originally depict ‘Hunters in a Forest’ – the title customarily assigned to M.78.9.11 – but a royal procession, with a prince riding in an idealized landscape followed by arms-bearers. When out on a hunt, Mughal rulers wore clothes of green and brown, helping them blend in with the environment [39] – not their finest, lustrous, colorful silk brocades: that would have put their costly robes in jeopardy, if not their lives. Significantly, the underlying princely rider also wears gold (on his Tāj, cloud-collar and dagger), and neither prince seems to be carrying the arms expected of a hunter. In Sharif’s composition, gold is not only lavishly expended on the rider’s figure (its surface beautifully enlivened through punching (fig. 52) but also on the sword casing held by one of the attendants (fig. 53). The gold casing is a detail even less consistent with a hunt scene, and one we cannot possibly attribute to later interventions. The attendants may in fact be arms-bearers: even the one added later still carries the bow and arrows in the manner of an arm-bearer, not as hunters do. Conversely, perpetuating Mongol custom, falconers had been in attendance of the Mughals’ ancestors ever since the time of Timur, and actually had a much longer history in the Eastern Islamic lands. [40] Although arms-bearers usually carry arms in their (often rich velvet) casings in Mughal hunt scenes, gold as a rule does not seem to be pertinent to the hunt context. [41] The drum, here carried by the ruler and his followers, is an ambiguous feature, associated both with the hunt and with the marching army, and will require further inquiry. One could furthermore argue that, as far as the original Shāhnāma illustration is concerned – which, it is worth recalling, only comprises one rider, the purported Akbar / Bahram Gur (or other legendary figure) – it hardly matters whether the subject depicted is a march or a hunt, the contents being in essence allegorical. It would nonetheless be important to establish a more precise connection with a specific episode. We must presume that Sharif, being the son of the author of the original painting, who was still alive then, would be adequately informed about the original content. Having suggested a possible context – a Nawroz presentation gift – let us now consider how he proceeded to make the painting his own. If, as we have suggested on the basis of strong evidence, the original composition was centered on the figure of Prince Akbar impersonating a literary figure such as Bahram Gur – could the rider in Sharif’s reworking not be Prince Salim – the future emperor Jahangir? That he is a prince of the blood is signaled not only by his brocaded robe, but by the black egret-plume sarpīch tucked in his turban – a hallmark of royalty with Timurid associations, often seen on Humayun’s Tāj. Salim would have been twenty-two in 999 H / 1591 CE, when Sharif painted his composition. The rider seems younger – but one must bear in mind that his facial features have been altered beyond recognition (fig. 54). Could the presentation gift have been made with an aim to identify the father with the son, and to equate both with a legendary king and hero of the past? Could the deliberate incorporation of a Humayuni relic, first created as the ancestor had regained the throne after long years of hardship, have further enhanced the value of the gift? Finally, would the gift have been made to the father or the son? Given the early date and the contents of the historical inscription (stressing Sharif’s affiliation to the Din-i Ilahi), more probably the former – or, at the very least, with the former’s approval, or possibly at the former’s behest. Interestingly, the very date of the painting suggests a possible alternative narrative. In 1589 CE, Akbar made his second visit to Kabul following the death of his brother Mirza Muhammad Hakim. On that occasion, we must presume that he acquired the latter’s library. It is possible that some manuscripts originally painted for Humayun had remained there. Perhaps the Shāhnāma was found damaged (the lower portion of the inner border, as mentioned, is missing), but Akbar was keen on having some of the pages preserved and ordered Sharif, as the son of the original author and one of his close associates, to devise a suitable solution in this instance. The latter then decided to paint an ‘auspicious’ picture of the emperor’s son similarly riding in an idealized landscape. [42] Alternatively, Akbar himself may have suggested the idea. Yet another – not necessarily incompatible – scenario is suggested by the choice of poetry in the innermost text panels, datable to no later than Sharif’s composition. A preliminary translation reads ‘I have lost all control of my heart; having slipped from my hand my heart has fallen into the path of sorrow. Involuntarily I have turned to the desert, never having spoken anything too much or less. Like a madman I have wandered on hills and mountains, my heart is free of all worry, big or small’. Especially when combined with the adjacent historical inscription, which stresses Sharif’s loyalty, they would seem to suggest that the author was seeking pardon for some offence or reproachable behavior. Although this may well be a means to celebrate his unbounded devotion to his master. Or – if we further assume the retainers to allegorically comprise the author – perhaps to Prince Salim, of whom Sharif was a close friend. [43] Whatever the prior history of the painting, if our reconstruction of the iconographic contents is correct, Jahangir would have been especially keen to preserve this image of himself in allegorical garb at the time when the ‘Gulshan Album’ was assembled. In this respect, the insertion of verses emphasizing the hunt as a spiritual quest at the top and bottom of the page is especially relevant. Our suggestion that the literary figure depicted might be Bahram Gur is further supported by the verses added to the outer border, as he is at once a hunter and a king. It would be very interesting to further explore this subtle textual-visual shift from the original content of the Shāhnāma painting – which, we must presume, essentially celebrated majesty – toward an affirmation of loyalty and discipleship, and finally an expression of mystical concerns. Each stage, we could argue, reflects the respective historical moment and a different stage in the development of the Mughal conception of royalty. [44] As we can see, there is plenty of material for further inquiry. In addition, we must presume that Sharif’s composition was at one time mounted into a frame not corresponding to the present one (and probably a smaller one). Its original appearance is purely conjectural, as no Akbar-period albums (or even album folios) survive, although we know that they must have existed: Abu’l Fazl’s reference to an album containing the likenesses of courtiers is most often quoted in support. [45] It is interesting that Jahangir and Shah Jahan dismantled and reconfigured Akbar’s albums, just as they demolished most of his buildings. This constant remolding and refashioning of forms, and the building upon such forms, will deserve all our attention in the future. In the domain of manuscripts, we have only begun to scratch the surface. In this respect, despite the fact that few if any instances of pages complete with borders incorporated into later compositions are likely to emerge in the future, the authors believe that many of the questions raised in this preliminary report are of broader relevance to our understanding of Mughal and Persianate albums, in terms of artistic choice as well as practice. The importance of some of the discoveries made cannot be overestimated. One more work has been added to the short list of paintings from the reign of Humayun. Not only that – but, corroborating Welch’s suggestion – an additional title has been conclusively added to the even more meager list of works illustrated for Humayun, which thus far only comprised the Paris Khamsa. This implies we should revise our assessment of the Kabul workshop significantly: so far, Humayun has been known almost exclusively as a patron of individual scenes centered on contemporary life. Together, the Paris Khamsa (painted in a far simpler style and significantly different from this work) and the two Shāhnāma pages compel us to rethink the relative weight of surviving evidence. If the border framing the mid-16th-century composition was the one originally conceived for Humayun’s Shāhnāma, we would be looking at the only surviving Humayuni painting preserved in a contemporary decorated border (the borders of the Paris Khamsa are plain). If the picture instead was reframed for insertion in an album, this could only have occurred in the first two decades of Akbar’s reign – whether at his court or in the Kabul workshop of his brother Mirza Muhammad Hakim. This would make the LACMA fragment the earliest known Mughal album page preserved with its border – and the only surviving Mughal album specimen securely datable to the 16th century. The verses selected by Sharif to accompany his Nawroz gift would seem to support the first possibility (a forgotten Shāhnāma page which was resurrected in order to stress loyalty to his master). But, while we hope to find further clues to substantiate or disprove this possibility, we cannot but emphasize that any of the hypotheses proposed implies a momentous discovery. Last but not least, consider the seemingly substantial discrepancy in quality between this work and the Paris Khamsa. The two Shāhnāma illustrations are small, but full-page and the coloring exquisite. Equally sophisticated is the relationship of image to text in the LACMA specimen, where the text is interspersed within the image, not simply juxtaposed with it. In order to account for this discrepancy, one would have to consider the possibility of either a different dating (with the Paris Khamsa preceding the arrival of the Safavid masters) or of a different patron (for instance, one of the dignitaries at Humayun’s court). Either possibility opens scenarios hitherto virtually unexplored for Humayun’s reign. As regards the extensions of the image panel, we have signaled some inconsistencies which might indicate that reworking continued beyond the chronology traditionally accepted by scholars. Any proposed dating or attribution for this portion of the image panel – which is premature at this stage – will have to take into account the peculiar history of the Gulshan Album as well as of this individual folio. As regards the former, the only secure information seems to be that the album was in Qajar Iran by 1263 H / 1847 CE. [46] Even though the relevant inscription, cited by various scholars, refers directly only to the main bulk of the album (now in the Gulistan Palace Library), the information must equally apply to the LACMA folio, if we accept Beach’s statement that “all the known dispersed pages appear to have come from Iranian collections”. [47] In addition, Beach (2004: note 3) mentions a faint inscription on pages 255-56 of the Gulistan Palace bound album which now contains most of the ‘Gulshan’ pages, referring to it as the “Album of Nadir Shah”. If this was the case, then the ‘Gulshan’ would have made its way to Iran as early as 1737 CE, along with many other Mughal manuscripts and works of art. This substantially affects our reconstruction of the history of the LACMA folio. As regards the latter, and as stated above, M.78.9.11 was acquired by LACMA in 1969 as part of the Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck collection. The history of the piece prior to its publication in 1966 is to date impossible to reconstruct – although it was probably among the folios which “began to appear publicly as early as 1912, when Victor Goloubev’s collection (formed between 1908 and 1911) was shown in Paris [...]. Marteau and Goloubev were the first known collectors of Jahangir album pages in Europe, and almost certainly acquired these from dealers in Paris.” (Beach 2004: 111). Any future work aimed at clarifying some of the iconographic features in the extensions that cannot immediately be identified as dating to the 17th century will accordingly have to take in all the said historical vicissitudes. The role of the folio within the Gulshan Album also merits further examination. The design of the floral frame on the recto of the page is better appreciated in the virtually identical border framing ‘Abd al-Samad’s Jamshid, discussed above, whose green background has been more fully preserved. Soucek (1987: 171) and Beach (2004: 115-117 and figs. 1-2) consider the two pages to have once constituted a single album opening, with the LACMA folio providing the left half of the composition. In support of this reconstruction, besides the similar arrangement of the pages (in particular, the calligraphy insets at the top and bottom, whose content will deserve further attention), the said authors cite the affinity in composition and execution between the image panels. The suggestion is tempting, and our research has brought to light even closer ties between the painted compositions. However, it has not as yet been clarified univocally whether openings containing borders of two different colors would have been acceptable in Mughal albums. [48] In addition, the image panel in the LACMA page was indeed enlarged, as Beach (2004: 117) notes; yet it still does not match that of the Freer panel exactly: the latter is slightly longer, extending a little further into the lower margin. Could this be only the result of miscalculation, or is it a signal that the two pages, despite their similarities, were not originally paired? [49] Alternatively, one may suggest, they could have formed part of a coordinated sequence. A more detailed study of the calligraphy panels will possibly yield some relevant clues. Needless to say, any future research moving from this inquiry and involving a more extensive study of the Gulshan Album will have to be concerted with the team of international scholars that has long been working on it. [50] At this stage, we hope that some of the issues raised by our research will contribute to enliven the debate and explore new territories. The image panel on the recto side of M.78.9.11 appears to be made up of at least four distinct pieces of paper. Its phases of intervention and paint layers, as we have seen, are equally or potentially even more numerous. Further research is needed before a detailed chronology is proposed for the entire object (comprising the recto and verso). We have focused in particular on the mid-16th-century page (original rider figure and early Mughal border). Sharif’s composition seems to have preserved or mimicked some portions of the original design to varying degrees. The artist may not only have extended the mountains, but also added a few figures, among which are certainly (based on iconographic and stylistic considerations) two of the riders following the central figure. Although an exceptionally complex palimpsest, M.78.9.11 epitomizes the necessity to approach items that were reconfigured and repainted at various times in their history without taking their ‘visible’ chronology for granted. It emphasizes the necessity to examine album pages by dissecting them – if only metaphorically (or, rather, visually, by applying available technology) – and examining each of their details independently. As our study of early Mughal materials progresses, it becomes increasingly clear that overpainting was the norm rather than the exception in the Mughal (and post-Mughal) reception of earlier materials. It is therefore exceedingly fortunate that a combination of circumstances has resulted in the finding and identification of this early work from the Mughal workshop, allowing us to speculate on its numerous successive avatars. We hope that our work will encourage others to approach works from this and other schools of Islamic painting with a fresh look. There is plenty out there to hunt for; the quest has only just begun. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Footnotes:

|

| BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beach (1966): Milo Cleveland Beach, ‘Mughal Painting’, in The Arts of India and Nepal: The Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection, Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, pp. 140-160, nos. 193-220. Beach (1978): Milo Cleveland Beach, The Grand Mogul: Imperial Painting in India 1600-1660, Williamstown (MA): Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. Beach (1987): Milo Cleveland Beach, Early Mughal Painting, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press. Beach (2004): Milo Cleveland Beach, ‘Jahangir’s Album: Some Clarifications’, in Arts of Mughal India – Studies in Honour of Robert Skelton, R. Crill, S. Stronge and A. Topsfield, (eds.), London-Bombay: Victoria and Albert Museum and Mapin Publishing, pp. 111-118. Beach & Koch (1997): Milo C. Beach and Ebba Koch (with translations by Wheeler M. Thackston), King of the World: The Padshahnama, an Imperial Mughal Manuscript from the Royal Library, Windsor Castle, London: Azimuth Editions and Washington D. C.: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Chandra (1949): M. Chandra, The technique of Mughal painting, Lucknow: U.P. Historical Society, Provincial Museum. Das (1994): A. K. Das, ‘Persian masterworks and their transformation in Jahangir’s Taswirkhana’, in Humayun’s Garden Party: Princes of the House of Timur and Early Mughal Painting, S. R. Canby, (ed.), Bombay: MARG Publications, pp. 136-152. Dickson & Welch (1981): M. B. Dickson & S. C. Welch, The Houghton Shahnameh, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 2 vols. Eslami (2002): Kambiz Eslami, ‘Golšān album’, in Encyclopedia Iranica, Ehsan Yarshater (ed.), Vol. XI, pp. 104-108. Harley (1970): R. D. Harley, Artists’ Pigments c. 1600-1835, London: Butterworths. Isacco & Darrah (1993): Enrico Isacco & Josephine Darrah, ‘The ultraviolet-infrared method of analysis: a scientific approach to the study of Indian miniatures’, Artibus Asiae, Vol. 53, No. 3/4, pp. 470-491. Johnson (1972): B. B. Johnson, ‘A preliminary study of the technique of Indian miniature painting’, in Aspects of Indian Art, P. Pal (ed.), Leiden: E.J. Brill, pp. 140-146. Kühn (1986): H. Kühn, ‘Zinc white’, in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of their History and Characteristics, Vol. 1, Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art. Leach (1995): Linda York Leach, Mughal and Other Indian Paintings from the Chester Beatty Library, London: Scorpion Cavendish, 2 vols. Lee et al. (1997): L. R. Lee, A. Thompson and V. D. Daniels, ‘Princes of the House of Timur: conservation and examination of an early Mughal Painting’, Studies in Conservation, Vol. 42, No. 4, pp. 231-240. Mason (2001): Danielle Mason et al., Intimate Worlds: Indian Paintings from the Alvin O. Bellak Collection. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art. Melikian-Chirvani (1998): Assadullah Souren Melikian-Chirvani, “Mir Sayyed Ali: Painter of the Past and Pioneer of the Future,” in Mughal Masters: Further Studies, Asok Kumar Das (ed.), Mumbai: Marg Publications, pp. 30-51. Melikian-Chirvani (2007): Assadullah Souren Melikian-Chirvani, Le Chant du monde: L’Art de l’Iran safavide 1501-1736. Paris: Musée du Louvre. Okada (1992): Amina Okada, Le Grand Moghol et ses peintres, Paris: Flammarion. Pal (1993): Pratapaditya Pal, Indian Painting: A Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection, Volume I, 1000-1700, Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Parodi (2006): Laura E. Parodi, ‘Humayun’s Sojourn at the Safavid Court (A.D. 1543-44)’, in A. Panaino and R. Zipoli (eds.), Proceedings of the 5th Conference of the Societas Iranologica Europæa, Vol. II. Milan: Mimesis, pp. 135-157. Parodi (forthcoming, 1): Laura E. Parodi, ‘From tooy to darbār: materials for a history of Mughal audiences and their depictions’, in Joachim Bautze and Rosamaria Cimino (eds.), Arts of the Mughal Court. Parodi (forthcoming, 2): Laura E. Parodi, ‘Two pages from the Late Shah Jahan Album’, Ars Orientalis, Vol. 40. Purinton & Watters (1991): N. Purinton and M. Watters, ‘A study of the materials used by medieval Persian painters’, Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 125-144. Richard (1994): Francis Richard, ‘An Unpublished Manuscript from the Workshop of Emperor Humāyun, the Khamsa Smith-Lessouëf 216 of the Bibliothèque Nationale’, in Confluence of Cultures: French Contributions to Indo-Persian Studies, F. N. Delvoye (ed.), New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 37-53. Roxburgh (2005): David J. Roxburgh, The Persian Album: from Dispersal to Collection, New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Schmitz (2002): Barbara Schmitz (ed.), After the Great Mughals: Painting in Delhi and the Regional Courts in the 18th and 19th Centuries, Mumbai: Marg. Seyller (1992): John Seyller, ‘Overpainting in the Cleveland Tutinama’, Artibus Asiae, Vol. 52, No. 3/4, pp. 283-318. Seyller (1994): John Seyller, ‘Recycled images: overpainting in early Mughal art’, in Humayun’s Garden Party: Princes of the House of Timur and Early Mughal Painting, S. R. Canby (ed.), Bombay: MARG Publications, pp. 49-80. Skelton (1994): Robert Skelton, ‘Persian Artists in the Service of Humayun’, in Humayun’s Garden Party: Princes of the House of Timur and Early Mughal Painting, S. R. Canby (ed.), Bombay: MARG Publications, pp. 33-48. Soucek (1987): Priscilla P. Soucek, ‘Persian Artists in Mughal India: Influences and Transformations’, Muqarnas, Vol. 4, pp. 166-181. Three Memoirs (2009): Three Memoirs of Homayun. Transl. and ed. by Wheeler M. Thackston. Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 2 vols. bound in one. Thompson & Canby (2003): Jon Thompson and Sheila R. Canby (eds.), Hunt for Paradise: Court Arts of Safavid Iran 1501-1576, Milan: Skira. Verma (1994): Som Prakash Verma, Mughal Painters and their Work, Aligarh: Centre of Advanced Study in History and Delhi-Oxford-Bombay: Oxford University Press. Welch (1985): Stuart Cary Welch, India! Art & Culture 1300-1900, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Welch et al. (1987): Stuart Cary Welch, Annemarie Schimmel, Marie L. Swietochowski and Wheeler M. Thackston, The Emperors’ Album: Images of Mughal India, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Welch (2004): Stuart Cary Welch, ‘Zal in the Simurgh’s Nest: A Painting by Mir Sayyid ‘Ali for a Shahnama Illustrated for Emperor Humayun’, in Arts of Mughal India – Studies in Honour of Robert Skelton, R. Crill, S. Stronge and A. Topsfield, (eds.), London-Bombay: Victoria and Albert Museum and Mapin Publishing, pp. 36-41. Wright et al. (2008): Elaine Wright, with contributions from Susan Stronge et al., Muraqqa‘: Imperial Mughal Albums from the Chester Beatty Library, Alexandria (VA): Art Services International. Zebrowski (1983): Mark Zebrowski, Deccani Painting, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. |

| Appendix: Analytical Instrumentation

Photography - UV fluorescence: Captured with a FujiFilm FinePix S3Pro CCD camera with Peca #916 UV/IR barrier filter and Wildfire mercury vapor lamps filtered at 365 nm. - UV reflectance: Captured with a FujiFilm FinePix S3Pro UVIR CCD camera, 18A filter and Wildfire lights (365 nm). Microscopy XRF Reflectance FTIR UV-vis spectroscopy |

[top]

asianart.com | articles