asianart.com | articles

Download the PDF version of this article

A Preliminary Survey of Gestures on Indian Icons and their Designation *

by Richard Smith

text and photos © asianart.com and the author except as where otherwise noted

September 09, 2015

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

1. Introducing the problem

The reader may find the word "preliminary" in my subtitle in need of explanation. Why a prolegomenon at this late date? Why preliminary when a glance through the glossary or index of most modern books on Indian art gives the impression that a system of iconographic hand gestures is already well understood? Perhaps the very verb tense we use, the present tense used in art historical writing, contributes to a false impression. It is similar to what has been called "the ethnographic present," much discussed and debated by anthropologists, a tense used to dehistoricize "traditional" cultures.[2] As much as possible, this essay will try to locate developments historically.

Because this essay zigs from physical objects to the texts and zags back again to the objects as it tracks the evidence through the centuries, it might help the reader follow along if I preview the main conclusions right here. Mainly, the term mudrā to designate a hand gesture, made by either an artistic icon or by a human, is a late occurrence. Then, when mudrā does occur, it seems more appropriate in ritual than artistic context. At the end (Part 12), I will try to understand how the use of the term mudrā came to be so common in art historical writing beginning around the turn of the twentieth century. (I should also point out, parenthetically and at the start, that readers will not find any reference to the commonly cited book on this subject, Mudrā by E. Dale Saunders. Justification for avoiding this book, written from the perspective of Japanese esoteric Buddhism, should be clear by the time readers near the end of this essay.)

"Preliminary" in my title also applies because my evidence is not exhaustive although it is representative (the body of examples is described in the next paragraph). The term applies as well to my own research, because the present survey is preliminary background to an examination of one specific gesture: the hands of the Buddha on sculpture where he is said to be "turning the wheel," often described by art historians with the Sanskrit compound dharmacakrapravartana mudrā. That focused study will follow at a later date.

This survey has three main features. First of all, it is chronological. Although the dating of evidence is often difficult in Indian culture, the study will try to follow historical developments. This makes if different from most discussions of mudrās which tend to discuss "meanings." The second feature is that this study is quantitatively based on a limited corpus of art objects. In Los Angeles, we are fortunate to have two important museum collections of South Asian art, so I have used those collections and their catalogs; also, I have used two major published histories of Indian art.[3] The third feature of this study is its limitation to the main Indian subcontinent; therefore it ignores early developments in the northwest which are the subject of debates over several issues including outside influence. As this survey proceeds, it will shift back and forth between the visual evidence and contemporaneous literary discussions of gestures.

2. An early gesture mentioned in texts

Let's begin with a couple of episodes from early narrative literature that describe people apparently making gestures. One is from an early Buddhist sutta, and the second is a famous episode in the Mahabharata.

First scene, with translation of passages by Maurice Walshe: A high cast Brahmin named Soṇadanda, with a large following of other Brahmins and householders, goes to see a rising teacher of a rival religious sect. He "approached the Lord, exchanged courtesies with him and sat down to one side. Some of the Brahmins and householders saluted [the other teacher] with joined palms."[4] This passage written down by the first century BCE in the Pali language uses the phrase añjaliṁ paṇāmetvā. The first word means the raised hands joined as a reverential greeting, the form of the word here appearing "only in stock phrases" according to the Dictionary, as here with the verbal form paṇāmetvā, from a root meaning "bend, stretch out, or raise;" so, the whole phrase implies bending over and raising up your joined hands in respectful salutation. Notice that the word "hand" or "palm" does not appear at this early date, nor any word that means "gesture."

Second episode, the well-known Story of Nala in the translation of Monier Monier-Williams: A beautiful girl named Damayantī is allowed to choose her own husband. In heaven, Indra and three of the other gods descend to earth as suitors, and they ask King Nala, who is also a suitor, to be their go-between. When the gods appear to him, Nala greets them "with folded hands adoring." Addressed by the gods, he then "with folded hands replied." When Nala then informs Damayantī that he arrives as a messenger of the gods, she "performed homage to the gods."[5]

The three phrases, in Sanskrit, are kṛtāñjali "having made añjali," prāñjali "with añjali before one," and sā namaskṛtya devebhyaḥ "having done salutation or homage to the gods." As with the Pali passage, the meaning of añjali is reverence, and certainly implies placing the palms of the hands together (not "folded" as the quoted translation gives). It is here combined with the verb "to do or make," or simply a preposition, "pra-." The third phrase uses the word namas, "reverential salutation, adoration, bow," combined with the same verb "do or make." In his essential book on iconography, J. N. Banerjea says he makes no distinction between the designations añjali and namaskāra, "the idea of reverence" is in both.[6] None of these phrases, however, use any word literally meaning hand or gesture.

My point is that when we look at visual evidence from this early period BCE, in the absence of written evidence using such phrases, are we correct in describing them as displaying the Añjali Mudrā, as historians often do?[7]

3. Visual evidence from centuries BCE to early CE

Let's now look at the visual evidence. From the Maurya period, third century BCE, we have several large stone yakṣī and yakṣa sculptures, now in Indian museums. These earliest extant figural sculptures do not make gestures. Although many of their arms are broken off, from what survives we can see that they are holding objects, usually a caurī, flywhisk. Free arms are usually placed fist on hip, or simply hang pendant and empty. These yakṣa/yakṣī nature spirits also appear through the second century BCE as carved decorations at the stupas of Bharhut and Sanchi. They continue to hold things, the females often a tree branch above, while their free hand continues to be placed on their hip. For these, we cannot use the term gesture, by which I mean intentionally communicating with the hands, as opposed to holding an object, letting the arm hang, or putting a hand on one hip.

Fig. 4The gesture of raising the hands palm to palm: The carved reliefs from these early stupas are covered with figures, mostly human but some divine, raising their hands palm to palm (figure 4). In groups or singly, they face objects of Buddhist worship such as bodhi-tree shrines, stupas, or a riderless horse signifying the great departure, and in scenes of Jātaka stories. The significance of this gesture, as in the two texts quoted above, is veneration.

Another gesture; raising the right hand, palm forward: A cakravartin or universal king makes this gesture on a first century BCE marble relief from southern India.[8] Although this gesture becomes common later, it is almost never seen on the earliest sculpture, nor is there any text to tell us what it means.

To follow a sequential progression from the periods before and after the Common Era, the images on coins become important since they probably depict imagery that existed in perishable materials, such as wood, that are no longer extant. Both Coomaraswamy and Pal argue for the importance of this numismatic evidence. Early coins, marked with a punch, are extant from about 500 BCE, but the marks are simple solar, animal, or nature images. By the second century BCE, cast and die-struck coins begin to show human figures. These figures, kings and deities, generally hold an object in their right hand and rest their free hand on a hip. By the first century CE, we begin to see gestures. On a silver coin a woman, probably a goddess of abundance says Coomaraswamy, places her left hand on her hip and raises her right hand palm forward. On a gold coin from the early second century, King Kanishka stands on one side while the reverse portrays a standing Buddha (his name in Greek letters) with his left hand holding his robe and right palm raised in front of his chest. A gold coin from around 200 shows a later Kushan king on one side with an early example of a multi-armed Śiva on the reverse; three of the hands hold attributes while the free right arm is extended in the palm forward gesture.[9]

This gesture, raising the right hand with the palm facing forward, becomes by far the most commonly depicted gesture on art from the mid-second to the third century. Under Kushan kings, patrons of more than one religion, we begin to see the earliest religious icons and their use of gestures. On Kushan coins, as noted, we have seen a goddess, Śiva, and the Buddha, all making the same gesture.

The creative center of Mathura, the capital city on the Jamuna River in northern India, produced a large number of stone images, still extant, for several religious sects. The LACMA collection includes several belonging to the second and third-century of goddesses, androgynous Śiva, and four-armed Śiva (figure 1), all raising their right arm, palm forward.

LACMA also has an important fragment of a seated Buddha, dated by Pal no later than the year 100. Its left hand is broken, but no doubt placed in a fist on the folded left leg. The right arm and hand are complete, shown raised with the palm forward and turned slightly inward. Coomaraswamy reproduces two complete examples which he dates to the early second century.[10] The Mathura sculptures that follow it all make the same gesture with their right hands raised. Huntington reproduces two seated and one standing Bodhisattva with their right hands raised, all from the second century, now in Indian museums. Huntington also reproduces a second century relief of four scenes from the life of the Buddha, where he even makes this raised palm gesture while teaching the first sermon (although in the conquest of Mara, he touches the earth). Coomaraswamy also reproduces a relief of four scenes from Amaravati in southern India; note well, the Buddha raises his palm in both the teaching scene and the conquest of Mara.[11] Clearly, the gestures of the Buddha were still in the process of being codified, and the "teaching gesture" has not yet appeared. The raised palm gesture dominates the early period, on images of any sect, in any context.

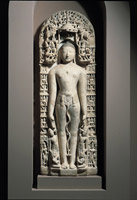

Fig. 5Throughout the Kushan period, figures in veneration continue to place their palms together and raise them. Good examples of this gesture are the scenes from Amaravati reproduced by Huntington, and a first century column from the Bharhut stupa, now in the Norton Simon Museum, where several figures perform this gesture toward the riderless horse in the scene of the Buddha's Great Departure. A new gesture also appears in the Kushan period: Seated figures place one hand on top of another, palms up, on their folded legs: the meditation gesture. Coomaraswamy reproduces one from the early second century, and Huntington from the third; both are, interestingly, Jain Tīrthaṅkaras (figure 2 shows this gesture on a later example). LACMA has a relief of a Buddha seated in this gesture, from third century Nagarjunakonda in southern India. Standing Jain figures also begin to appear making a gesture that no other religious icons use: arms hanging down and intentionally not touching the body. Although this does not really look like a gesture, its intentionality and readability makes it so, and the Jains give it a name, kāyotsarga, body abandonment (figure 5, on a later example). Huntington reproduces one, carved at Mathura, from the third century.

4. Early theoretical classifications of gestures

By the time Kushan domination declines near the end of the third century, the same ancient gestures of raising the right palm, or raising both palms joined in veneration continue. In the same period, a couple of new gestures are being introduced; we have noticed Jain figures seated with hands placed in the lap, or standing with arms suspended away from the body. In the early fourth century the first emperor of the Gupta dynasty takes the throne in northern India, and by mid-century they have established a wide empire. Under the Guptas, especially from the late fourth and continuing after their collapse around 550, there is an expanded development of figural types at several sites, as well as developments in the literary and performing arts that manifest in theoretical treatises that relate to this survey of gestures.

The study of gestures, their description, purpose, and codification, is first applied to the movements of performers on the stage. The Nāṭya Śāstra, "Drama Treatise," of Bharata is the locus classicus for this literature. The date of this text is usually aligned with the writings of Kalidasa, the great playwright and poet who probably wrote during the reign of Chandragupta II from around 375 to 412. The "conundrum," as Edwin Gerow describes it, is whether "the theory is a codification based on Kalidasa's works, or do the works reflect an already conventional theory, on which the plays were modeled?" The text, he concludes, "is generally considered to be a compilation of settled traditions rather than an authored work and roughly contemporaneous with Kalidasa."[12]

The Nāṭya Śāstra (NŚ) of Bharata the Sage covers theatrical performance through a wide range of topics, from the construction of the theater to the performance of the actors and actresses. It focuses on specific parts of their body from the eyes and head to the legs and feet, as well as the total body in walking and other movements. For our purpose, only Chaper Nine is important, "Gestures of the Hands," as it is usually translated from hastābhinaya,[13] although abhinaya properly means performance, not gesture. Other words from the text often translated by "gesture" include aṅga and its derivatives aṅgahāra and aṅgika, although these properly mean limb or body part; even so, the dictionaries give "gesticulation" for aṅgahāra. The specific word combined with each gesture to give it its technical term is hasta, hand, not, as of this date, mudrā. So we have the first of 24 disjoined, asamyuta, or single-handed gestures, which is called Flag-Hand, patāka hasta.

Patāka would appear to be the gesture that we have seen on sculptures since the Kushan period, "all the fingers are extended keeping them close together with the thumb bent." So, this is the gesture of raising up the palm. The text helpfully tells us how this gesture is applied in performance; twenty eight applications are listed, but none of them, such as "delight and pride in oneself," are even close to the meaning of the raised palm given by art historians. If we use the Nāṭya Śastra as our guide to interpret a statue of Śiva raising his palm, he might just be "warming himself by the fire." When later texts, including modern authors, describe artistic icons making this raised palm gesture it is, without variation, indicating "do not fear," abhaya. Not so, unfortunately, according to the Drama Treatise, which does not give this meaning among the twenty-eight.

Fortunately, another text overlaps with the NŚ, though it is later; how much later is difficult to tell as extant manuscripts of both texts are hundreds of years later than their supposed composition. The Mirror of Gesture, Abhinaya Darpaṇa (AD) by Nandikeśvara, is a shorter compendium based largely on Chapter Nine of the NŚ.[14] Note that the modern translators have also rendered abhinaya as gesture, rather than its proper meaning dramatic performance. For the first "hand," patāka hasta or flag hand, the AD gives forty-one diverse "usages: night, river, world of the gods, horse, the seven cases [of Sanskrit grammar]" and so forth. Then, the text adds, "according to another book,"[15] sixty-six additional usages: "saying Victory! Victory!, clouds, forest, crying Ha! Ha!, pouring rain" and so forth, with only a few of these overlapping with the NŚ. In the middle of this list we find "removing fear," its standard meaning in the iconography of art. The odds of guessing that this gesture means "do not fear," based on the lists in the AD and the NŚ, would be far less than the odds of drawing the King of Diamonds, with his raised palm, out of a card deck.

Fig. 6A nearly similar gesture to flag hand, in both the NŚ and the AD, is half-moon hand or ardha-candra hasta. The NŚ says all the fingers are bent "depicting a bow," though the AD describes it as the flag (a flat palm with all the fingers extended) but with the thumb stretched out (figure 6; but note that the captions A and B should be reversed). Thus it is "the moon on the eighth day of the dark fortnight" and a dozen other applications, while the NŚ gives this hand sixteen usages, but none in the lists of either text signifying "do not fear." The AD, however adds further information about the use of some gestures by various devas, and ascribes the origin of the half-moon hand to Śiva. Śiva, depicted on that gold coin of ca. 185-220, might indeed be the earliest deva shown making this raised-palm gesture. This gesture, says the text "originates from the desire of Śiva for ornaments, of which the moon is one" which, indeed, we see placed in the hair of most Śiva sculptures. Unfortunately again, the raised palm does not indicate "do not fear," its standard art historical description; it signifies the moon. Also, this too is "according to another book," and see my footnote 15 on what this actually means; it is not from the actual text of the Abhinaya Darpaṇa.

The performance treatises are not completely useless in aligning later textual interpretations with the art objects. Among the lengthy discussions of hand positions, there are a couple, but only a couple, of gestures that apply to the icons. The NŚ describes "Keeping the forefinger, middle finger, and thumb without any intervening space," as hamsāsya, swan-face. It is "used to indicate fine, small, light things." The AD describes swan-face slightly differently, with only "the tips of the forefinger and thumb joined." And, "according to another book," says the AD, "this hand is derived from Dakṣiṇāmurti Śiva when he was teaching the sages." This gesture, its interpretation as teaching, and its use by that particular form of Śiva, is a direct match with the icons as we will later see (Part 10), although later it is given a different name, vyākhyāna and later still vitarka. Notice that this matching description, its interpretation as teaching, and its use by Śiva, also come from "another book."

There is one complete match between the performance treatises and the iconography, and this is found among the thirteen joined hands, samyuta hasta, in the NŚ. It conforms to añjali, palms joined in veneration, and here is its description in the NŚ: "Two patāka hands are put together. This is called añjali. It is employed to greet friends, receive venerable persons, and making obeisance to deities." The text also tells us that it is held to the head for deities, near one's face for venerable persons, and on the breast for greeting friends. The AD agrees in all details. The name, description, and its significance agree with the iconography except for calling it a hasta, which much later comes to be termed mudrā. As we proceed, please keep this word hasta in mind. This word for hand, the earliest technical term for a codified gesture, will stay with us until the very end.

I have discussed the Nātya Śāstra and the Abhinaya Darpaṇa at some length because it reinforces an important point in my paper, namely that there are chronological disjunctures between artistic developments and their later textual interpretations. The great authority on iconography, J.N. Banerjea, dismisses this literature in one sentence; "such works on dramaturgy as Nāṭyśāstra, Abhinayadarpaṇa, etc., have no practical application in our present study."[16]

Banerjea's dismissal of the performance treatises is accurate regarding the study of visual iconography; if the art portrays actual dancers, however, these texts often apply. Kapila Vatsyayan has written a thorough study of the relation between classical Indian dance and literature.[17] Though she focuses on dance, rather than religious icons, she attempts to collate several performance treatises, such as the NŚ and AD (and five from later centuries) with iconography in her Table XII. The collation with iconography seems often forced, as when she lists patāka, flag, when raised or lowered, "as abhaya and varada mudrā." Certainly, the form of these gestures, an open palm, is the same; but, the performance literature interpretation is irreconcilable with the icons, as I have discussed above. Some of the others in her list of twenty four hasta/mudrās also bear some relation with the icons, but most don't. Vatsyayan is better when focused on dance proper, and she reproduces 155 photographs of sculptures which show dancing figures performing the many gestures and postures from the texts; a few of these are early, but the majority eighth to thirteenth centuries.

Vatsyayan also claims to find references to the dance gestures in early narrative literature. When Rāma returns from exile to Ayodhya, his brother and the citizens proceed out to greet him "and their Añjali hastas seem to be full blown lotuses." So she writes the technical dance term, but here is what the Sanskrit actually says: sa kṛtāñjaliḥ, "he makes añjali." An adjacent passage gives the Sanskrit prāñjaliyaḥ sarve nāgara, "the whole town extending añjali." The vocabulary and grammar of both of these passages are nearly the same as the Sanskrit phrases I quoted near the beginning of this essay. Neither of them use the technical term from the dance literature "the añjali hasta," as she has translated, because hasta does not appear in the text. But then, Vatsyayan discovers gold: "the first evidence of the technical language of the dance." And, "the first appearance of a real hastābhinaya term, besides añjali, is the padmakośa hasta."[18] In the performance literature, this gesture was listed among the single-handed hasta; it means lotus bud, and the NŚ says it "represents offering of Puja to a deity." She does not date the evidence, but Patrick Olivelle places this text by the poet Aśhvaghoṣa in the first or second century. A group of women approach young Prince Siddartha as he rides along the street in a chariot and, so quotes Vatsyayan, "they pay him homage with padmakośa hands." It does sound like a reference to the padmakośa hasta, but here is the Sanskrit: padmakośa nibhaiḥ karaiḥ, "by making like lotus buds." No word hasta, so it is not quite the technical dance term.[19]

These gestures from the codified lists of the performance texts do not have a clear presence in early literary texts, yet scholars often see them belonging there. The tendency is to want such gestures to appear old, or ancient, as if antiquing a piece of furniture, and historical sequence gets muddied. Act One of Kalidasa's play Abhijñānaśākuntala, The Recognition of Śakuntalā, is an example commonly cited. There, in the famous scenes of "watering the trees," and "defending against a bee's attack," modern scholars assign specific gestures supposedly made by the actress portraying Śakuntalā. Both Vatsyayan and Coomaraswamy supply several named gestures from the performance treatises that the actress would have employed.[20] Both scholars, however, openly give their source for these specific gestures as the Arthadyotanikā commentary on the play by Raghavabhatta, although his date is late fifteenth century, post-dating the play by a thousand years.[21] Whether the actress at the time of Kalidasa used these gestures is a guess, for in both scenes, the playwright uses only the simple stage direction nirūpayati, "she performs" watering the trees or defending from the bee's attack.[22] Interestingly, the word mudrā actually appears near the end of Act One, where the heroine's two friends read out the letters of the name on the king's mudrā, his signet ring.

The general problem of classifying gestures, as the discrepancies between the performance treatises and iconography expose, is that writers tend to classify gestures in one domain of human activity that does not apply to a different domain. In western civilization the classification of gestures begins with the Roman rhetorician Quintilian, who published a book on oratory, actually a guide for lawyers arguing before a judge, toward the end of the first century CE. Like the Indian performance treatises, in his chapter on delivery, Quintilian discusses movements of the head, eyes, hands, down to the feet and walking (or not) while pleading one's case. One gesture he describes is striking in its similarity to the Indian "swan-face hand" (described in my Part 4); he describes it as "placing the middle finger against the thumb and extending the remaining three. It is suitable," he recommends, "for the exordium (the introduction of the oration), and is also useful for the statement of facts."[23] Thus we have the vitarka mudrā in ancient Rome. A similar rhetorical gesture is used even today, as we see frequently in Barack Obama's "pinch of spice" gesture. Other hand gestures described by Quintilian are not similar to the Indian texts, and apply only to rhetorical argument, although he does describe an "unusual gesture in which the hand is hollowed and raised well above the shoulder." Looks like "patāka" or "abhaya," but Quintilian gives it the different purpose of exhortation.

Gesture Studies has started up as an academic discipline in the US and Europe since the mid-1990s, with its own journal and international conferences. The best-known of these scholars is Adam Kendon, who traces the history of classifying gestures from Quintilian to the present. Kendon candidly describes the field of gesture as "messy," and he concludes that "no attempt should be made to develop a single, unified classification scheme."[24] Kendon's own interest is the interrelation of gesture and speech, and how gestures are "a flow of movement organized into phrases of gesticulation." So, his approach is not ours, but he describes a scheme useful to any study of gestures, which other scholars have named "Kendon's Continuum." At one end he puts the kind of spontaneous movements that people make to accompany their speech. At the other end of the spectrum are conventionalized sign languages such as those used by deaf communities. So, speech with flapping hands at one end, and at the opposite end gestures without speech. This continuum seems to describe what has happened to The Nāṭya Śāstra of the sage Bharata, which was discussed earlier in this essay. In the twentieth century, this treatise on spoken theatrical performance with gestures has evolved into Bharata Natyam, pure dance with gestures but no speech.[25] I will return to Kendon, and his discussion of some individual gestures, later in this paper.

In the sculpture of the Gupta period, the most common gesture continues to be the raised hand, palm forward. Coomaraswamy's plates XL and XLI reproduce a large stone standing Buddha from Mathura and the famous Sultanganj bronze Buddha, standing larger than life; both sculptures raise their right palm. The stone example is dated fifth century, and Coomaraswamy dates the Sultanganj bronze to early fifth century. Huntington, along with other art historians, dates this famous piece two centuries later, seventh.[26] The Norton Simon Museum collection contains a smaller metal standing Buddha similar to the simple style of the Sultanganj, and dated stylistically to circa 550, while LACMA has a more decorated version in metal from the late sixth century; all of these with raised palm. LACMA also has a seated stone Buddha showing this gesture; dated second half fourth century from Mathura. For the purpose of this essay, even dating some of these bronzes late becomes evidence of the persistence of this raised palm, the earliest of the Buddha's gestures (my Part 3), even as new hand positions begin to appear.

Fig. 7In the Gupta period we begin to see a gesture similar to the raised palm, but with the arm lowered, palm out. This is traditionally interpreted as bestowing a gift or a boon. Huntington reproduces an early standing stone image of Avalokitśvara making this charitable gesture, dramatized by nectar flowing from the hand and feeding hungry ghosts below. The image is from Sarnath and dated 475. This gesture becomes more frequent in the post-Gupta period and later. Kendon discussing gestures as "visible utterance," discusses the vertical palm and the lowered with open palm as a pair.[27] The vertical palm, he says, "indicates an intention that what is being done be halted; the semantic theme is interrupting, suspending, or stopping a line of action." This this agrees with the later Sanskrit term, abhaya, the gesture of "do not fear." The lowered open palm gesture, Kendon says, "has the idea of offering or giving, even let me offer an idea or let me give an example." So agrees with the later Sanskrit term, vara or varada, granting a boon. Just in case we don't assume that such meanings are universal or obvious however, remember that when we make this gesture with both lowered hands, it means "I don't have anything to give you;" or, in the US in recent years, this both palms open gesture has come to mean, "Hey, you lookin' for a fight?"

Other earlier gestures that continue through the Gupta period include the hands resting in lap with palms up, or "meditation," usually called dhyāna. We see this gesture on Jain images (figure 2 is from the end of this period), which also hang their hands in kāyotsarga. Coomaraswamy and Huntington both reproduce fifth-century seated Buddhas also making this meditation gesture. We still see hands together in āñjali, usually made by attendant figures alongside the main Hindu or Buddhist image. The non-gesture of holding objects also continues, the Buddha holds his robe, attendant figures hold a flywhisk or a thunderbolt, and Hindu images increasingly hold attributes in their multiplying arms.

Sometime in the fifth century, the Buddhists introduce an important new gesture, perhaps at Sarnath or maybe elsewhere. The seated Buddha puts his two hands together in front of his chest in a complicated "teaching" gesture." [28] (Figure 2 shows this gesture on an image from a couple of centuries later.) Perhaps the best-known version of this gesture is found on the sculpture in the Sarnath Museum dated to around 475.

From the late fifth century there are many Buddhist sculptures carved at the caves of Ajanta. The large stone images frequently raise their right palm, or lower it in varada, even making this offering gesture in the scene with Mara's hosts; thus the gestures are still not strictly coded to the events of the Buddha's life. Also, the main shrine images at Ajanta perform the new teaching gesture. Huntington's Chapter twelve, "Buddhist Cave Architecture," illustrates many of these figures.

In the post-Gupta period, from the late-sixth century and later (Coomaraswamy's "mediaeval"), striking changes appear in the art. We see greater elaboration of decoration, multiplication of deities and forms, both Hindu and Buddhist, and increasing attention to the gestures made by these deities.

I have studiously avoided using the term mudrā to refer to gestures. The Sanskrit word certainly exists in the periods I have been discussing, but it has not taken on the meaning of "gesture." The period when it does finally denote "gesture" is not easy to determine. In Pali, the language of the earliest Buddhist texts, mentioned near the beginning of this essay (Part 2), the word is spelled muddā. The Pali Text Society's dictionary gives the following meanings: a seal or impression, the art of calculation (that is, counting on the fingers); suffixed to the word hattha, hand, it means sign language, which comes close to the meaning of gesture. In Hybrid Sanskrit, the language of the earliest Buddhist Mahayana writings, the meanings are the same as in Pali, plus also, wages (because a coin bears an impression). The Hybrid dictionary also gives "position of the hands," but the citation is to the Mañjuśrīmūlakalpa, which is probably 8th century. In Sanskrit, mudrā means a seal or signet-ring, its impression, anything stamped such as money, a sign, badge or authorization, lock; and, eventually, please pay close attention to this quotation: "names of particular positions or intertwinings of the fingers (commonly practiced in religious worship and supposed to possess an occult meaning and magical efficacy)." This dictionary entry by Monier-Williams is as much a commentary as a definition, but it draws attention to two significant features: "the fingers" and its use "in worship." Both of these features will be noticed when we look at the texts. Monier-Williams cites four texts for this meaning, three are from later periods, and one is a book written by himself in 1883.[29] We will look at more Sanskrit dictionaries on this word in Part 12, where I discuss the terminology of modern art historians.

It might be pertinent to mention that early Buddhist and Hindu literature do not focus on the hands. The Pali texts say simply that the Buddha folded his legs and sat down, not mentioning what he may have done with his hands. The early Mahayana texts such as the Amitābha and Perfection of Wisdon Sutras do not mention the hands of the many Buddhas and Bodhisattvas who appear, despite the later significance of gestures as identifying features on icons of these characters. While the Buddhist Jātaka stories and the Hindu Purāṇas are important for interpreting narrative scenes depicted in art, they mention only one common gesture; as human or divine figures approach a deva they often place their palms together and bow.[30]

The word mudrā, denoting gesture, must date from sometime after the Nāṭya Śāstra of the Gupta period, since that text uses exclusively the word hasta, hand. Does the word apply to artistic icons? A couple of relevant early texts are the Bṛhat-Saṃhitā and the Viṣṇudharmottara-Purāṇa. The Bṛhat, compiled by the polymath Varahamihira who died in 587 is, in the words of Banerjea, "the earliest datable iconographic text." Chapter 57 of this encyclopedic text deals with the details of sculpted icons. Most of it is taken up with iconometry, the precise measurements of images from their forehead down to their toenails. Occasionally, we get the prescription for a gesture. Here is Banerjea's translation: "The worshipful god Viṣṇu, represented as eight-armed, should show in his right hands a sword, a mace, an arrow, and abhaya mudrā, etc. If four-armed, his right hands should show an abhaya mudrā and a mace, etc."[31] Even though his translation gives abhaya mudrā, the Sanskrit of these phrases is śāntida and śāntikaro, giving peace and making peace. I do not see the Sanskrit word mudrā anywhere in Chapter 57 of the Bṛhat-Saṃhitā. Again, as pointed out in my Section 5, we see a translation quite different from the original language of the text and the scholar supplying the word mudrā.

The Viṣṇudharmottara is an upa- or secondary Purāṇa that may date to the seventh century.[32] Its third Khanda praises "the worship of deities in beautiful images constructed in accordance with the principles of painting, and painting is dependent on dancing."[33] So, in chapters 17-31 the text discusses dance, nṛtya, including its gestures. The discussion is lifted entirely, with minor variations, from the NŚ, including its lists of single-hands beginning with patāka, followed by joined hands, then dance hands; the term is always hasta, hand. In chapter 32, however, we get something new: Hasta-mudrā, hand gesture, and a list of rahasya-mudrā, secret, mysterious, esoteric gestures.[34] Note the arrival of the word mudrā meaning gesture. Here is one: "cakra—the tips of the two madhyama (middle) fingers and two thumbs are joined with one another." (I think this may mean both thumb tips touching and middle tips touching, rather than each hand individually; this forms, with my small hands, a four-inch-diameter circle.) Thus it appears to resemble its designation, a cakra, a wheel or circle. Although, it does not at all resemble the cakra gesture of the Abhinaya Darpaṇa, which is both hands palm to palm crosswise; nor does it resemble the dharmacakra mudrā of the Buddha. These fifty-seven Secret Mudrās "signify gods with their insignias, their syllables, the vedas and vedāṅgas." Although this text introduces the word mudrā, it has nothing to do with iconography, which is covered later in the Viṣṇudharmottara, Chapter 34. That chapter discusses the making of images of deities, their number of faces and hands, but nothing about hasta or mudrā gestures. So what do these secret gestures have to do with? Here is Priyabala Shah in her study of the Viṣṇudharmottara, trying to understand what she has just translated: "Those desiring the highest siddhi should show these Mudrās in accordance with the Mantra, the Deva, and the Vidhi. The meaning seems to be that the mudrās should have relations to a deity, the spell, and ceremony . . . the gods are related to the spells (Mantras) therefore the various Mudrās described above should be practiced after knowing the mantra or spell." Vidhi in Shah's first sentence is the word she translates in her second as ceremony, or we could say the ritual. In our study of gestures, we are no longer in the studio of the sculptors or on the stage of the actors, but seem to have wandered into the Temple of the Freemasons. Since I am making many claims in this essay, I want to focus of the importance of these chapters from the Viṣṇudharmottara. Two points: in its discussion of iconography, this seventh-century text does not use the term mudrā; when it does use mudrā, the term applies to the complicated positions of human hands used secretly in rituals.

Tantric texts are often referred to by art historians because they contain detailed descriptions of many deities, and usually these references are to Buddhist texts useful for explaining Buddhist icons. A rare and valuable Hindu text for this approach is the Tantrasāra, a late-16th century compendium of previous texts from as early as the tenth century, with some ultimate sources going back to the Gupta period.[35] It gathers together 148 Hindu sādhanās, practices whereby the practitioner, sādhaka, visualizes himself as the deity, with all her (most of them are goddesses), or his, physical details including the hands. The practice involves dhyāna, which usually means meditation, but here means visualization. The Tantrasāra uses the term mudrā for the gestures of these visualized deities, but not always. Here are the statistics: the 148 dhyānas in the text mention gestures 60 times. Most of the 2-10 hands for each deity are holding attributes, so there is not always a free hand to make a gesture. The text uses mudrā as the word for gesture 4 times (and once more mudrā means "parched grain," one of the five tantric M terms, according to Pal's Introduction to the Tantrasāra, page 14). A few times the older term hasta is used, or karāṃ, a synonym for hand. Several times we see the verb give, da, especially with the offering gesture; once, the text seems to address the practitioner with the verb bhavasi, "you do reassurance and offering." The most common gesture in the Tantrasāra is vara/varada, offering/give offering (or favor, or boon), 28 times. Second is abhaya, do not fear, 26 times. 5 dhyānas give a gesture for teaching or wisdom, named as vyākhya, cin, or jñāna (these are similarly formed by touching a fingertip to the thumb tip). Threatening, tarjanī, appears once. This, in fact, is the name of the forefinger in Sanskrit; to note cultural differences, western culture calls it the index or pointing finger. This gesture goes back to the sūcī hasta, needle hand, of the Performance Treatise (NŚ), where one of its many applications is "representing anger by shaking the forefinger." A very curious aspect of the Tantrasāra is that, while all the deities and their visualizations are tantric, tarjanī is the only tantric gesture named in this text that also appears on sculpture. As we shall see, it is used by icons of fierce tantric goddesses. Ninety percent of the gestures in this Hindu tantric compilation are the traditional raising or lowering the open palm. Also, note well, the word mudrā is only one of a variety of terms used to describe what a hand is doing.

In Buddhist tantric literature also, we begin to see the use of the term mudrā for gestures made by the hands of the deities as well as by the devotee. The development of a Buddhist "pantheon" during the Pala period, from the 8th to the 12th centuries, sees an increase of the number of gestures as well as their complexity. Most historians begin this development with the Guhyasamāja Tantra, which has been given a wide range of dates, but probably belongs to the mid to late eighth century.[36] So here is, as nearly as it can be located textually, the beginning of the use of mudrā as a term for the hand positions of visualized tantric Buddhist deities. This early Tantra begins like a Mahāyāna sutra, with a vast assembly of divine characters requesting a teaching. The teacher, called the Lord Bodhicittavajra, responds by sitting in meditation and hypostatizing five Buddhas in a maṇḍala. They are often referred to as the five Dhyanī Buddhas, but the Guhyasamāja calls them the Jina, or Victor Buddhas. Here are two of the five, as they first appear, in a translation by Benoytosh Bhattacharyya: "The Lord sat in a special Samādhi (meditation) and his whole form started resounding with the sacred sounds of vajradhṛk which is the mantra of the Dveṣa family. No sooner did the words come out than the sounds transformed themselves into the concrete form of Akṣobhya with the earth touching mudrā. Then the Lord sat in another meditation and soon became vibrant with the sacred sounds of jinajik, the principal mantra of the Moha family. The sounds condensed themselves into the concrete form of Vairocana with the Dharmacakra mudrā."[37] Thus the gestures that, during the Kushan and Gupta periods were seen on images of the historical Buddha, earth-touching, teaching, offering, meditation, reassurance, are now assigned to these five fantastic hypostases of Tantric doctrine. Hereafter, the historical Buddha is sidelined from both the texts and the art.

Following the meditative generation of the first five Buddhas, the Guhyasamāja goes on to describe further meditations, mantras, vibrations, and condensations resulting in five goddesses who are given as queens to the five Jina Buddhas. Subsequently, later texts will populate their maṇḍalas with proliferating "families," kula, of bodhisattvas and their female partners. Two of the most important texts for expanding the number of these Buddhist deities are the Sādhanamālā, a collection from the twelfth century of 312 earlier sādhanās, and the Niṣpannayogāvalī, a text from around 1100 that collects visualizations for 26 maṇḍalas containing more than 600 deities. Many of these deities display gestures. For the (literally) uninitiated, a sādhana is politely, a visualization practice; or bluntly, a conjuring ritual. It is not the instructions for sculpting an icon although these texts were apparently followed by sculptors.

Fig. 8In his book on the Sādhanamālā, Benoytosh Bhattacharyya gives a lengthy translation of sādhanā number 98. It describes what the worshiper, sādhaka, should do from the moment of getting out of bed in the morning through an extensive set of preliminary rites, whereupon the worshiper is told to visualize the goddess Tara by following descriptive prescriptions in the text. This description includes her "showing the gift-bestowing signal (mudrā) in the right hand." Then follows this instruction to the worshiper: "The Mudrā or mystic signal should be exhibited. The palms of the hands should be joined together with the two middle fingers stretched in the form of a needle. The two first fingers should be slightly bent, their tips touching the third phalanges of the first fingers. The two third fingers should be concealed within the palm and the two little fingers should be stretched. This is called the Utpala Mudrā or the signal of the night lotus" (which is the flower Tara holds in her left hand). Finally, the worshiper should chant a mantra, Oṁ Tare Tuttāre Ture Svāhā and "think of his own form as that of the goddess."[38] Notice that the mudrā is linked to the mantra, a ritualized linkage we have seen since the first appearance of our word in my Part 8.

For the study of gestures, two features of this ceremonial practice are important. Earlier, I quoted Monier-Williams' dictionary definition for a late meaning of mudrā as "intertwinings of the fingers used in worship." We see both those features in the above quotations from this sādhana. A tantric mudrā is primarily the complicated positioning of the fingers, and it is used by the worshiper in his devotions. Notice that the goddess Tārā herself makes the simple and traditional hand gesture of offering, palm lowered, as we see her doing on sculpted icons (figure 8).

Many other Tantric and Mantranaya texts produced through the Pala and later dynastic periods name countless mudrās which are used in the rituals by priests, monks, or devotees. The Mañjuśrīmūlakalpa alone, a text translated into Chinese by the end of the 10th century, lists 108 mudrās, which are combined with their mantras.[39] Here is one; the translation is by Glen Wallis: "Homage to all Buddhas whose teachings are indestructible, Oṁ riṭi svāhā! This is the vidyā [spell] that does everything; it is called 'lovely hair,' the female companion of Mañjuśrī. During all rituals requiring an attendant, the great sealing gesture, 'five crests' is used." (Sanskrit, mahāmudrāyā pañcaśikhāyā; the second word indicating that the mudrā imitates the five crested hairstyle?)[40] Throughout this literature, as translated here, the word mudrā means a "seal," it seals the mantra. Also, the translator has added the word "gesture," which is not in the Sanskrit; "great seal" would be close enough.

Fig. 9Hundreds of these gestures are listed in tantric texts; N.N. Bhattacharyya mentions several texts with large numbers of mudrās, and he highlights those that he considers "the common Tantric mudrās." He gives nine such, all with mysterious names such as avaguṇṭhaṇa, "the veil", or dhenumudrā, "cow gesture."[41] J.N. Banerjea also selects "at random" eight mudrās from a late Vajrayana manuscript. He illustrates them all with drawings and gives their mantras. One shows fists back to back touching knuckles, its mantra is Oṁ vajradīpe svāhā, which contains the word lamp, and he claims the gesture "may represent a lamp." Another, six fingers interlaced with forefingers extended and touching tips, has the mantra Oṁ vajranaivedya svāhā, which includes the word offering (figure 9, #4 and #6). Banerjea stresses that these "complicated hand poses were mainly ritualistic in character, adopted by the sādhaka in the performance of his sādhanā."[42] I would also note that these Tantric gestures are all very symbolic, as opposed to the older gestures for which we could use Kendon's term "quotable gestures," gestures for which a verbal expression also exists; for his modern example, finger circling the ear can be verbalized "he's crazy."[43] The gestures seen on older Indian art are likewise "quotable": hand lowered with palm facing out, "Here, I'm giving you something;" hands resting on the lap, "I'm just sitting here thinking." The Tantric gestures are mostly not quotable; they are symbolic of something elsewhere (as above: a lamp? a cow?). You need to interpret: "This mudrā stands for X" (as I did above: This mudrā represents the five-crested hairstyle of Mrs. Mañjuśrī). The tantric gestures mean something; they do not say something. Tarjanī might be an exception, "I'm warning you!" One more comment on translation. In these tantric texts, the meaning of the term mudrā is "seal;" the hand gesture is related to a mantra, and it seals the mantra. Translating the word as seal would be enough, without adding or substituting the word gesture, or just leave it untranslated. Think of it like this: If a government official asks me to provide a thumbprint, I will roll my inked thumb on a piece of paper (or, these days a digital sensor). Shall we say I am making a thumbprint, or am I making the thumbprint gesture?

I will finish with a look at the art from 700 to 1200, at which time the Buddhist religion comes to an end in India, though production of Buddhist art continues in the Himalayan and farther countries. Hindu and Jain art also continue, but the development of their iconography has culminated. The sections in Huntington's and Coomaraswamy's surveys of this period, plus the LACMA and Norton Simon Museum catalogs, show numerous, and increasingly female, Hindu and Buddhist icons from these centuries. Noticeably, despite their multiplying arms, attributes, and elaborate tantric iconography, the majority of gestures made by their free hands are the same gestures displayed in the previous periods: the palm raised in reassurance, or lowered in offering. Occasionally, one figure will make both these gestures with separate hands. And, sometimes, the hands do double-duty, performing a gesture while also holding an attribute such as a string of beads or a flower. The third most frequent gesture in this period is one of teaching, variously formed with one hand and variously named vitarka, vyākhyāna, cin-, jñāna, or with both hands, dharmacakra. Once in my body of evidence, this vitarka gesture is formed by a couple of Jain nuns, touching their thumb and index fingers with their palms turned up, rather than facing forward as usual.[44] Another new use of this gesture is by Śiva in his Dakṣiṇāmūrti, or south-facing, form. Huntington reproduces one with its arm broken, but both LACMA and the Norton Simon Museum own examples from Tamil Nadu, from around 950 and 1100. Śiva raises his right hand touching the tips of the index and thumb as he expounds the scriptures (figure 10). Pal calls it cinmudrā; Banerjea uses the term vyākhyāna for this form; whereas the dhyāna of Śiva Dakṣiṇāmūrti in the Tantrasāra (my Part 9) called it jñāna-mudrāḥ. To compound the problem, as pointed out in Part 4, this gesture was given to Śiva in one of the performance treatises, where it was named hamsāsya hasta, swan face hand. So, for some gestures there may have been more than one valid expression.

Fig. 10The meditation or dhyāna gesture, hands placed on lap, is less common in this late period. It is used by an occasional image of the Buddha or a Jain tīrthaṅkara. Jain images also continue to hang their arms down away from their body. Even though N.N. Bhattacharyya names a couple of Jain texts that list nearly two hundred tantric mudrās,[45] Jain art does not use them. The gesture of veneration, palms together, continues to be used by attendant figures (figure 8), but also appears on the principal image of Avalokiteśvara as Ṣaḍakṣarī, the embodiment of his six-syllable mantra. Huntington reproduces an 11th century example from Bihar, and the Norton Simon Museum has an example from West Bengal, about the same period. Of its four hands, two hold attributes while the front two are placed palm to palm. Pal points out that the image "conforms to a description in the Sādhanamālā." The artistic representations are now following the texts, although, as noted above, the sādhanā texts are ceremonial not iconographic prescriptions. This añjali gesture, while continuing to signify veneration, has occasionally taken on sectarian connotations. Banerjea discusses how Purāṇic stories subordinated various other deities to the primary deity, and this influenced the sculptors. Thus we see Viṣṇu and Brahma beside Śiva "with their front hands in the Añjali pose." Beside images of the Buddha, Indra and Brahma place their palms together, in Banerjea's wry phrase, as "mere acolytes of the Buddha."[46] The añjali gesture thus indicated subordination of the Hindu gods.

Several late period Buddha images also touch the earth with their right hands, referred to as the bhūmisparśa mudrā. Pal suggests this gesture was invented at Bodh Gaya, where the historical Buddha is supposed to have touched the earth. Although, during this period, images of the Buddha making the traditional gestures may not be the historical Śākyamuni, but rather any of the five Jina Buddhas who also make the traditional gestures, as we read in the Guhyasamāja Tantra. Huntington reproduces a Pala period Buddha touching the earth, and points out that the figure is actually Akṣobhya; and another figure with varada gesture that could be mistaken for Śākyamuni, but is really Ratnasambhava.[47]

Fig. 11While the identity of tantric goddesses and gods becomes obvious by iconographic features such as their attributes, specifically tantric gestures in this final period are few, as the traditional gestures continue to predominate. I have already mentioned the tantric gesture tarjanī, the raised finger of threatening (figure 8). It is used by Parṇaśabari, a wrathful female form of Akṣobhya from 11th century current Bangladesh. Describing a sculpture of her six-armed and three-faced form, Huntington writes that it "closely follows the textual description of the goddess given in the Sādhanamālā." She mentions "her front left hand in tarjanī mudrā." Again, an art historian supplies the word mudrā, while the ascribed textual source does not have it (Sanskrit: hṛdvāmamuṣṭitarjanyādho "right fist with threatening finger over the heart").[48] Another, more common, tantric gesture is that of crossing the wrists facing into the chest while holding a thunderbolt and a bell, vajra and ghaṇṭā, in the hands. This two-handed gesture is called vajrahuṁkara. Huntington reproduces two eleventh-century sculptures of Samvara, another wrathful aspect of Akṣobhya. Describing the image from Orissa, she says it "follows the description found in the Niṣpannayogāvalī almost exactly." From the same period, the Norton Simon Museum has a stele of transcendental Buddhas and goddesses; the central figure holds the front two of his six hands in this vajrahuṁkara. The NSM also has a metal image of Heruka making vajrahuṁkara (figure 11). A couple of other unique gestures appear on late tantric images. Vairocana grasps his upraised left forefinger in a gesture called bodhyaṅgi. The Norton Simon Museum has a delightfully mean looking Cāmuṇdā from the tenth century, who seems to bite her left pinkie finger. Despite the proliferation of ritual gestures in tantric sādhanas and related texts, as well as the multiplication of arms on icons which hold tantric attributes, the gestures of the free hands in art tend to be few and traditional.

Useful to this survey is the final chapter, "Tantric Art: A Review," of N.N. Bhattacharyya's book on tantric religion. After sections on "Tantric Architecture" and "Sexual Depictions," his chapter looks at "Tantric Icons."[49] Bhattacharyya describes icons from seemingly all the major museums throughout India, with four pages on the Hindu and nine pages on the Buddhist images. He is not looking specifically for mudrās, but if the icon is gesturing, he says so. By my count, here is what he found. He names a total of twenty-two gestures: fifty percent he calls vara or varada, the gesture of offering; the others are abhaya or reassurance, meditation, and teaching. Bhattacharyya's survey thus reveals the same conclusion as my own: a surprisingly conservative retention of the same traditional gestures that first appeared in Indian art of the early centuries, with a few more being added during the Gupta period. Even though there are developments in the theory and number of hand gestures, in the performance as well as the tantric literature, with few exceptions those gestures do not enter into the art.

The final evidence to look at conjoins the two aspects of my survey: the artistic depiction alongside the textual designations of gestures. In 1900 Alfred Foucher published a study of Buddhist iconography based on "new documents," six currently in the Cambridge University Library and one in The Asiatic Society, Kolkata. Of these manuscripts, two are most important, Cambridge MS Add. 1643 (dated 1015), and Kolkata MS A. 15 (dated 1071). Both of these contain texts of the Perfection of Wisdom in 8,000 Verses; though from Nepal, not India proper, Add. 1643 is the earliest illustrated manuscript from that country, and they both date from within decades of the earliest known Indian illustrated manuscript.[50] Both of these palm-leaf manuscripts are important not primarily for the text they copy, but mostly for a series of small paintings they contain. These small paintings, totalling 85 in Add. 1643 and 37 in A. 15, do not illustrate the text, but portray a series of Buddhas and Boddhisattvas, both male and female. Most importantly, these miniatures are accompanied by short texts alongside, which Foucher calls inscriptions, though I will use the word captions. The captions, written in early Nepal script, give the name of the deity along with its place of worship (mostly in eastern India, but also parts of western and southern India, also Nepal, China, Java, and Sri Lanka). A few captions also include the name of the gesture that the image of the deity is making. So, in the eleventh century, for the first time, we have artistic icons conjoined with simultaneous texts on the same page naming their gestures.

Fig. 12Introducing these small paintings (5.25cm. high, the full height of the palm leaf, and about 6cm wide), Foucher writes "Even at the scale of the miniatures, it is possible for us to recognize the principles of the mudrās." He then names and describes six "mudrās" that are becoming (perhaps under his own influence?) a canonical list. The only gesture he does not call a mudrā is "namaḥkāra or añjali." For nearly 200 pages, Foucher describes the deities, their mudrās, their postures, their attributes, and their historical context. Throughout, plates from his own photographs reproduce many of the miniatures with their captions. At the very end, Foucher prints his edition of the Sanskrit captions with his translations and comments. Of 122 total in both manuscripts, only a few, just three, name gestures. Here is what they say; I will quote all three. 1) First, from Cambridge MS Add. 1643 (Foucher's catalog of miniatures and inscriptions I, 7), mahāsamudre rāhukṛta abhayapāṇi The painting shows a Buddha, and Foucher translates "standing on the ocean," [by the way, that's not the word mudrā in the first word; it is samudra, ocean]. Also, the face of a demon appears in the water ("Rāhu?" guesses Foucher). So, the designation is weird, but the name of the gesture is clear: abhaya-pāṇi, "don't-fear-hand." Foucher does not mention it. 2) From Kolkata MS A. 15 (catalog II, 5), mahāsamudra rāhukṛta abhayapāṇi The painting is similar to the previous. Foucher also translates "Buddha standing on the ocean," and with this caption, he also translates the final word, "the right hand makes the gesture (le geste) of reassurance;" gesture he says, even though the text gives the word pāṇi, "hand." 3) Also from MS A. 15 (catalog II, 10), siṃhaladvīpe dīpaṅkara abhayahasta The painting duplicates the previous, which Foucher refers to, and does not translate the caption. The caption identifies it as Dipankara, on the Island of Ceylon (?), with "don't-fear-hand." (figure 12) In this caption, notice the use of the word hasta, hand, which is simply a synonym for pāṇi in the first two examples. So, of the three mentions of hand positions in these two eleventh-century texts, the number of times the texts use the word mudrā is zero. Instead, the texts use two words for hand. Also, it is curious, the only times any gesture is named, it is for similar paintings of, apparently, the Bodhisattva Dipankara. Nevertheless, Foucher has introduced these manuscripts with a lengthy discussion of many mudrās, including frequent use of the term abhaya-mudrā, and even redundantly abhayapāṇi-mudrā, the one gesture actually named, even though the manuscripts do not use the word mudrā. The captions never use the word mudrā when describing the iconic images. Furthermore, it is probable that the words for hand, pāṇi and hasta, do not imply "gesture." Sanskrit dictionaries as well as grammars point out that these two words in such compounds are often possessives; thus: abhaya-handed.

In 1905, Alfred Foucher published Part 2 of his Buddhist iconography study, this volume based on four texts that were still unedited. Two of these, dating to the mid-twelfth century and on palm leaves, are in the Cambridge University Library; two others, on paper and modern, are at Cambridge and Paris. These manuscripts are of a very different genre from the manuscripts of Foucher's 1900 volume; these are all ritual sādhana texts.[51] His main example, in fact, Cambridge MS Add. 1686, dated 1165, is one of eight Sanskrit manuscripts edited by Benoytosh Bhattacharya as the Sādhanamālā in Gaekwad's Oriental Series, two volumes, in 1925 and 1928 (Bhattacharya's English translation of this is discussed in my Part 9). Foucher summarizes the contents of these texts, the main one containing "around 150 sādhanas," but some 300 in all. I will concentrate on the gestures. Foucher prints excerpts of about 35 Sanskrit sādhanas with French translations. Here, more or less, is a numerical tally of the terms for the position of the hand or hands in Foucher's excerpts. Nouns: mudrā 11 times, hasta 3 times; Verbs: da 10 times, others used once or as supplement to a noun, da, dharam, karena (forms of give, bear, make). It is not surprising to see the word mudrā in these texts, they are esoteric ritual tests, and my Part 8 demonstrated that since the seventh century, mudrā described the ritualistic positioning of the hands and fingers, or the hands of the deity invoked by ritual visualization. Also not surprising is that almost all the gestures in examples given by Foucher are traditional gestures such as we saw in the Hindu and Buddhist tantric texts of my Part 9. His Sanskrit texts give abhaya, varada, samādhi (for hands on lap in meditation), vyākhyāna with a textual variant dharmacakramudrā, also dharmamudrā. Tarjani is one of the odd tantric gestures named; and, there are a couple more curious tantric gestures. One is mudrāṃ bandhayet, which Foucher translates as "le geste magique," the magic gesture, although it actually says, addressing the practitioner and not describing the deity, "one should bind the mudrā," followed by complicated instructions for clenching the fists and extending the forefinger, middle, and thumb "in the shape of a closed flower, then recite" and it gives a mantra (the deity in this sādhana visualization text, however, makes both the traditional "vyākhyana and varada mudrā").[52] Another interesting named tantric gesture is karaṇa mudrā. The first word just looks like "making" or "performing," but Foucher leaves it untranslated, "the fingers in karaṇamudra." In a footnote, he pleads ignorance of the exact position of the fingers. B. Bhattacharyya, however in the glossary to his translation, provides the description "index and little fingers erect, thumb presses the two remaining fingers." The deity of the sādhana is Hayagrīva, and Huntington reproduces a small eleventh century metal sculpture, where he seems to be making this gesture.[53]

I appear to be repeating the discussion of tantric mudras in my Part 9, but I want to draw attention to what Foucher is doing with these texts as we transition to my Part 12 on designations. In his two volume study of Buddhist iconography, Foucher has used two different genres of texts in his 1900 Part 1, and 1905 Part 2. The first volume discusses actual icons, with an occasional named gesture. The second volume discusses esoteric ritual texts where the gestures are made by the practitioner or the visualized diety. Nevertheless, Foucher treats them as equal, which we see by his use of vocabulary. In both volumes, his discussion of each deity is in three parts: a preliminary discussion, followed by the Sanskrit text, and then his translation. In the preliminary discussion he almost always uses the word mudrā, while the Sanskrit texts, of which I have given many examples, use a variety of words. In his translation of the word mudrā, or even if the text uses some other word or no specific word, Foucher consistently uses the word gesture, French le geste. Here is what I believe to be true about Alfred Foucher's contribution to Indian art history: Foucher has standardized the use of the word mudrā for the hands of artistic icons; and, more surprisingly (at least I was surprised when I began to figure it out) he has standardized the translation of mudrā as "gesture."

Here is a cold fact: not a single Sanskrit dictionary gives the meaning "gesture" under the word "mudrā." I checked eight, dating from 1819 to 1929; also two English-Sanskrit dictionaries, three Pali dictionaries, and one English-Pali dictionary. Not one tells me that mudrā means "gesture." The most ancient meanings of Sanskrit mudrā, and Pali muddā, as we saw in my Part 8, are a seal, signet, seal ring, stamp, or impression (see my Part 5, final sentence). Our earliest modern dictionary, that of Horace Hayman Wilson in 1819, gives these and related meanings, plus a late meaning "a mode of intertwining the fingers during religious worship." In 1868, Böhtlingk and Roth give the standard meanings plus "fingerstellungen, oder fingerverschlingunen bei religiösen vertiefungen," finger positions, or interlaced fingers in religious absorption. Above in Part 8, I quoted Monier-Williams in 1899 giving a similar meaning. Vaman Shivram Apte in 1890 gives "name of certain position of the fingers practiced in devotion or religious worship." All of the others give similar meanings, and Franklin Edgerton in his 1953 Hybrid Sanskrit Dictionary adds "meanings not in Sanskrit;" none of them are gesture. In reverse, two English-Sanskrit dictionaries, Monier-Williams in 1851 and V. S. Apte in 1884, do not give "mudrā" sub verbo "gesture." I do have to confess; I found it once. A. P. Buddhadatta in his 1957 Concise Pali-English Dictionary (for use by students in schools and colleges) gives the meaning "gesture" for muddā, but this has to be wrong for this word at the early date of the Pali texts; and, in his 1955 English-Pali Dictionary, this same author does not give "muddā" among the three Pali words s.v. "gesture."[54]

Also during the nineteenth century, while the above scholars were studying the language, other moderns were beginning to study the art as part of their investigation of the archeological remains of early Buddhism. Probably the first person in the modern period to systematically investigate the artifacts, and write about what he found, was Alexander Cunningham. Cunningham went to India in 1833 as young military engineer and, due to his spare time enthusiasm for exploring the ruins, ended up three decades later as Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India. Though trained as an engineer and not as a scholar, he had mastered certain periods of India's chronology and learned the languages well enough to translate inscriptions. When Cunningham uncovers sculpture, however, and looks at it, he has no art historical vocabulary to influence his eye. At the stupas of Sanchi in 1851 he uncovers some sculptures of the Buddha. Here is what he sees: "The statue is seated cross-legged, with both hands in the lap, palms upward . . . This is no doubt a statue of Sākya Sinha, the last mortal Buddha, seated in the very attitude in which he attained Buddhahood." No one ever says it better. Here is Cunningham describing a relief showing the Dream of Maya: "Three figures with joined hands adoring a holy Bo-tree enclosed in a square Buddhist railing."[55]

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a variety of terms are being used for the hand positions of Indian figural art. It may not be important to find who initiated the use of what term, but the publications of a few scholars became the source of many later references and citations. Studies of "northern Buddhism," especially, seem to have colored the vocabulary. In 1895 L. Austin Waddell published The Buddhism of Tibet, or Lamaism. Waddell introduces the images of "the Lamaist pantheon" as they are depicted in paintings and sculpture. He lists nine of "the chief attitudes of the hands and fingers (mudrās)," trying as best he can to give the Sanskrit names, but he seems to be back-translating from Tibetan, and sometimes makes a guess with a question mark. For example, "The hand elevated with the palm to the front (Skt. ? abhaya)" Others, he gives the names that are becoming standard, bhūṣparṣa. Some he guesses a non-standard name, e.g. "palm to front, and pendant with fingers directed downwards; refuge-giving (Skt., ṣaraṇ)." (Waddell's own emphasis in italics on the word "downwards." Correct transliteration of the Sanskrit would be śaraṇa, but the gesture is nearly always called vara, a boon; Waddell lists this meaning as a separate gesture, but equal in form.)[56] And sometimes, he comes up with a name that is nothing like the later standard name, "Index finger and thumb of each hand are joined (Skt. Uttara-bodhi)." Twice, Waddell gives the Tibetan but doesn't even guess a Sanskrit word, e.g. "The Pointing Finger, a necromantic gesture in bewitching."[57] I'll let my reader provide the Sanskrit for this one. Foucher lists Waddell's book in the bibliography of his L'Iconographie bouddhique de l'Inde and cites it throughout in his footnotes. Alice Getty in her 1914 The Gods of Northern Buddhism includes both Waddell and Foucher in her bibliography and gives thanks to Alfred Foucher for reading her manuscript and helping, especially, with the Sanskrit "as I am not a Sanskrit scholar." Nevertheless, throughout Getty's book, all the gestures have Sanskrit names plus mudrā; she defines eleven, even namḥkākara which Foucher doesn't even designate as a mudrā.[58] Getty's book then becomes a common source of citations for later scholars.

It appears that scholars in this period are groping around for some authority to help them name what they are looking at. It is fashionable to criticize these people for their colonialist arrogance, but I don't think that is the problem here; the problem is the fondness of scholars at all times for their own technical jargon. The Sanskrit language, and the elaborate terminology of northern Vajrayāna Buddhism provide them with that jargon. A good example of their groping is Buddhist Art in India by Albert Grünwedel. This book was published in German in 1893, translated soon after into English by A.C. Gibson, then revised and enlarged by James Burgess in 1901; it is this last version that appears in most scholars notes and bibliographies, so that is what I will discuss.[59] Here, we are told of "the truthfulness of the Tibetan tradition" when understanding the mudrās. The section on mudrās cites Waddell's book on Lamaism, Foucher's book on iconography, and another on Tibet. The illustrations on adjacent pages depict images from all over the Asian map, from Gandhara to modern Japan, to Siam and elsewhere, with only two of ten photographs of images from sites in the Indian Subcontinent. The title of the book, I remind you, is Buddhist Art in India. Another book that gets frequently cited, also supposed to be about India, is Hendrik Kern's 1898 Manual of Indian Buddhism. In his brief discussion of "the mudrā of images," Kern writes about the five "Dhyāni-Buddhas common in Nepal, Tibet, and Mongolia," and he cites books dealing with those countries by Waddell and others.[60] In saying these things, I do not want to lessen the accomplishments of this pioneering generation of scholars, especially their assignment of iconic hand gestures to the "life events" of the Buddha, or their resourcefulness in employing esoteric texts to identify the varied icons of later art. They were finding their way through pathless woods and left good maps for others to follow. My concern, as my title states, is with the usage of one word.

Also during the early years of the twentieth century, native Indian writers were beginning to promote nationalist ideals of art, and with that, Sanskrit vocabulary. The Modern Review, published in Calcutta, was a forum for educated Indians to write about political, economic, and social issues. In 1912 in that journal, the Bengali artist Samarendranath Gupta contributed the article "With the five Fingers."[61] He had gone to Ajanta, still remote in those years, and copied many drawings from the frescos. He reproduces many of them in eleven plates, which he uses to illustrate his call for "the reconstruction of a national art based on the revived ideals of the nation." These drawings from Ajanta thus "serve as the basis of an independent and self-feeling art." The drawings "require very little by way of explanation, for the mere outlines are quite expressive and speak for themselves." Gupta's first plate illustrates "two hands forming a mudra or symbolic expression." Two years later, in that journal's Bengali-language sister publication, the artist Abanindranath Tagore, guru of the above S. N Gupta, introduced readers to the Sanskrit terminology of the bhaṅgas, or bends of the body, in "Some Notes on Indian Artistic Anatomy."[62] That this terminology is unfamiliar is clear from his need to explain the Sanskrit term tribhaṅga, or thrice-bent, as well as other Sanskrit terms. In 1914 also, Ananda K. Coomaraswamy contributes "Hands and Feet in Indian Art" in The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs.[63] He opens with an amazing quote from Leonardo da Vinci to entice his European readers, about the attitudes of the limbs to represent the intentions of the soul. Then, of course, he moves to the limbs in Indian art, particularly "those positions of the hands called mudrās." He describes and names several mudrās of the Buddha. His article is illustrated by some plates, four of which are from Ajanta paintings "traced by Babu Samarendranath Gupta," the author of the recent article I just discussed. Coomaraswamy also uses one of Gupta's drawings for a plate in the back of his book three years later, The Mirror of Gesture, discussed in my Part 4. Then, in 1927, Coomaraswamy published his great History of Indian and Indonesian Art, a book that became the authority for the rest of the century. This is one of the publications I mined for visual data as explained in my Part 1. Throughout his book, Coomaraswamy prefers the designation mudrā, and their Sanskrit names: abhaya, dhyāna, dharma-cakra, vyākhyāna, and bhūmi-sparśa mudrā.

Fig. 13In this period of growing fashion for Sanskrit terminology, especially the word mudrā, and the citing of the same secondary sources (Coomaraswamy is an exception with many references to primary texts), one scholar stands out for his independence. In 1914, T.A. Gopinath Rao published his pioneering Elements of Hindu Iconography.[64] In his Introduction, Rao discusses his sources; "The Sanskrit authorities relied upon in this work are mainly the Āgamas, the Purāṇas, and the early Vedic and Upanishadic writings." His next sentence is very polite, but critical; "the Āgamas and the Tantras do not appear to have received much attention from modern scholars." That is no longer true, but it certainly was at the time of his writing. At the end of his Introduction, Rao gives his "List of the Important Works Consulted." The list consists of eighty Sanskrit works. Throughout his two volume book, Rao is flying solo with only these texts to guide him. I do not notice that he cites any modern scholar. When he gets to "the terms used in connection with the various poses in which the hands of images are shown," on page 14, "each pose has its own designation." The designation is hasta, hand; and he gives the eight "most common." So, he starts with varada-hasta and abhaya-hasta including descriptions. A couple have two names, kaṭaka-hasta or siṁha-hasta, "that pose of the hand wherein the tips of the fingers are loosely applied to the thumb so as to form a ring. The hands of goddesses are generally fashioned in this manner for the purpose of inserting a fresh flower." One is two-handed, the familiar añjali-hasta. Kaṭyavalambita-hasta we saw frequently on early sculpture; it is the arm lowered with hand resting on the hip. Another also involves the entire arm and hand, daṇḍa-hasta or gaja-hasta, arm and hand thrown straight forward like a stick or the trunk of an elephant; famously, this is the front left hand of four-armed Śiva while dancing (figure 13). Rao uses hasta for all of these, which word I assume he is finding in his texts. The book's Plate V illustrates all of these with drawings. Rao does introduce the term mudrā following the hastas, but his information raises suspicions. "There are also certain other hand-poses which are adopted during meditation and exposition. They are known by the technical name of mudrā." So, "are known by" (passive voice) where exactly? Can we assume, since they "are adopted during meditation and exposition" that his sources are devotional and ritualistic, not iconographic, thus the mudrā is adopted by a priest or worshiper? He doesn't specify his sources. If, however, he has discovered that term in an iconographic text, my argument loses its legs; I doubt it though, based on his discussion. He names them: the chin-mudrā or the vyākhyāna-mudrā, the jñāna-mudrā and the yoga-mudrā. In spite of his description of these Sanskrit technical terms, once Rao begins his discussion of the icons in the bulk of his book, he consistently uses the English word "pose." The goddess Durgā, for example, "front right hand should be in the abhaya pose."