asianart.com | articles

Download the PDF version of this article

by Erberto Lo Bue [1]

text and photos © asianart.com and the author except as where otherwise noted

October 19, 2015

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

Tucci's observations on the subject are found less in scholarly works than in reader-friendly articles, often untranslated, published chiefly in Italian periodicals and spanning a period from his first expedition to Ladak in 1928[3] to the last one to Tibet in 1948. Some of those travel accounts have been reprinted, often with fanciful titles different from the original ones and with an incomplete text in at least one instance, in a volume that does not do justice to the great scholar, bearing the title of one of his articles, "Nel paese delle donne dai molti mariti" ("In the Country of the Women with Many Husbands"), preceded by a foreword by an Italian journalist and including occasionally wrong captions under the illustrations.[4]

Indeed the Italian scholar, thanks to his genius, to his training in classical studies and to his thorough linguistic competence in several Asian as well as European languages, was able not only to delve deeply and extensively into different fields — against the current trend leading to knowing more and more of less and less, often resulting in insufficient contextualization and narrow understanding —, but also to write texts for a general public without sacrificing scholarship, to the extent of publishing books conceived as chronicles of his expeditions or diaries, a term appearing in the subtitle of his To Lhasa and Beyond, in parallel with his scholarly ones.

Tucci distanced himself "from the barren 'philologism' of Italian universities; on the other hand, using philology as a privileged means to enter the ancient world, he learned an incredible amount of habits and customs contemporary to him, a live but traditional culture (…)."[5] It has been suggested that the Italian scholar was able "to lay aside his huge baggage of notions to become more and more what a man of science is ultimately: a dreamer, a man looking around himself and to the future, or to the past, with the joy and stupor of a child, and his mind empty, open to the world. Indeed an empty mind, the ability to see new things also in those already seen, is the characteristic lacking in many scholars, to whom culture is a list for memory or a confirmation of certainties, a body of data already known to work out according to a pre-established order."[6]

It should be pointed out, however, that in his approach — shared by the Italians who assisted him in Tibet as photographers or physicians — Giuseppe Tucci was closer to Ippolito Desideri or Laurence Austen Waddell than to the many writers who have contributed to the Western "Orientalist" construction of the myth of the Land of Snows as an idealized exotic and highly "spiritual" place.[7]

In his writings meant for a general public, always based not only on his fieldwork and on his linguistic and historical competence, but also on a rationalistic as well as respectful approach, Tucci tried also to assess the state of Buddhist practice in Tibet, expecting seriousness from a religion and culture of which he had a deep understanding and which he held in high esteem: "The current idea is that lamaism[8] is a hotchpotch of magic rites with no spiritual substance. Lama and wizard are mixed in the minds of most people. One has to be clear about that. There is some truth in such statements inasmuch as Buddhism is going through a period of decadence in Tibet; the institution of great monasteries has been fatal to the development and purity of religion. Great monasteries have spread like parasitic organisms, where all too often practical interest replaces the sincerity of religious inspiration; the monk vegetates through his quiet life sheltered by the monastery, supported by donations, bequests, estates.

The huge growth of the community has acted as a contrary force to the refining of ascesis or to the purity of meditation. Schools have been organized in great monasteries and at most, besides the countless populace of ignorant clergy, doctors and dialecticians have been formed who know all the subtleties of literature and ritual, [who] are very clever at asserting the postulates of their system against those of rival sects in well-contrived logical discussions, who are in short the Tibetan copy of Indian pundits or scholars, miracles of learning and of memory."[9]

Elsewhere the Italian scholar explains:

"Surely, to a traveller not having had the opportunity to stay in Tibet for long or, not knowing its language, not realizing what he sees, the impression afforded by Tibetan Buddhism is that of a farraginous idolatry: all those rites which are performed mechanically, without an intelligent participation of monks, that reading of sacred texts of which one immediately sees that most 'priests' understand nothing, that multitude of idols, not all serene or chaste in their aspect, heaped on altars, that crowd of monks greedy of gains and suspicious, make one think that religion has gone down really to a low place. However, one ought to remember that such Buddhism is, so to speak, the transplanting into Tibet of one of the latest offshoots of the Buddhism of the Great Vehicle and specifically of those schools that are called Mantrayana and Vajrayana (…).

If one does not understand this value of the iconography and of the liturgy of tantric Buddhism, which is indeed the one introduced into Tibet, one cannot understand the innermost meaning of this religion, which however, indeed because of that prevalently initiatic character of its own, was not made to spread into the gigantic monastic organization of Tibet and much less into its lay crowd. Ultimately it was a religion suitable to a narrow circle of chosen people able to understand the rite in its deep meaning (…): but once it came into contact with the mass, that Buddhism could not keep the purity of its conceptions (…): but that should not lead us to condemn all Tibetan Buddhism, for there were indeed, and indeed there are even today though in ever decreasing proportions, very noble people in whom Mantrayana becomes true in its purity. (…) I do not wish to maintain that monasteries have extinguished the spiritual life emanating from Buddhist theories: there is no doubt that for a long time in monasteries a great multitude of masters and doctors was educated, who clarified, investigated, glossed the teaching received from India and therefore handed down the exegetic systems followed in the great Indian universities, with a fidelity of which we cannot find a match either in China or Japan (…).

Then the plethoric development of monastic institutions made lose in quality what was gained in quantity: the greater the number of monks, the lesser their intellectual and spiritual preparation. Rather than reliving religion in its inner depth, they were contented on one hand with formulas and rites or else, on the other, with arid logical and dialectic disciplines replacing the anxiety of a spiritual palingenesis with theological reasoning. And then the decadence started or rather, to say it better, increased in monastic milieus since from early times a certain tendency to formalism and to the cult of the literal sense had come about, to the detriment of spiritual understanding."[10]

Having made it clear that “Tibetan monasteries, which have generally turned into noisy nurseries of monks who are not always learned or pure, originally rose as hermitages” and that “the very name designating them in Tibetan means 'solitude, recess'”,[11] Tucci describes the situation in monasteries in the area of Mount Kailasa in the following terms:

"Now, in the general decay that has stifled all élan of spiritual life and destroyed all political glory in this land sacred to the memory of Buddhism, monks are scarce and ascetics even more so. Keepers exploit the places entrusted to their care and live exploiting the religious tradition and memories of those hermits who achieved their spiritual perfection in the past centuries. The fear of the marauders that infest the nearby valleys and may come down at any moment from the passes above leads pilgrims to seek shelter in these monasteries, which turn into noisy hostels and dormitories, in which languages and religions blend and join in friendship under the brigands' threat. Monks are happy to afford this hospitality, which is not just a human and charitable action, but yields not inconsiderable prebends to them and to the monastery. Because, here too, lamas are greedy for money and eager for trading. That is why monasteries are almost deserted: monks have gone down to fairs to sell, barter, do business, impart blessings and cast horoscopes."[12]

Obviously Tucci expected greater religious seriousness in a country that he regarded as the heir of the Buddhist traditions of India, which he held in high esteem, and which he had studied in great depth thanks also to his vast linguistic competence, including the knowledge of Sanskrit and Tibetan. One might argue that the official religion in his own country was not always practised seriously in monasteries and churches, and that perhaps he expected more from the Tibetan clergy than from the Italian one. However, he was right in relating the decadence of religious practice in Tibet to its political situation: "The same political decadence that has devastated the country is reflected in its religious life: the blind cult of the letter has replaced ancient mystical ardours that made these regions one of the most celebrated countries in the history of Buddhism."[13]

As far as the state of conservation of religious sites, images and texts in West Tibet is concerned, Tucci's judgments leave hardly any doubt about its cultural decadence thirty years before the Cultural Revolution, as may be gathered from the following passages:

"These temples (…) are complex pictorial evocations of the whole of Tibetan religiosity and of its symbols: one is filled with sorrow by seeing them on the way to decay. Rabghieling, perched on inaccessible crags, hosts just three or four monks who do not abide by monastic rules with excessive scruple. Its chapels contain precious statues in gilt bronze, silver, wood, heaped as in a junk dealer's storeroom, dusty, topsy-turvy volumes, in a muddle (…). Shangtzè and Shang (…) hardly keep a few precarious small chapels: doors knocked down, marvelous frescoes on the way to decay, precious paintings rolled up in a corner like old and unusable stuff. The former is in the hands of a half-witted monk sent there for punishment; the latter is entrusted in turns to the custody of three or four families making up the village. (…) At Ri the temple of Rinchenzangpo is about to fall: the roof lets the water through, wearing the paintings away and flaking the stucco statues. And everywhere, thrown haphazardly, a great quantity of manuscripts of all sizes and of all ages."[14]

Fig. 1 |

Fig. 2 |

Fig. 3 |

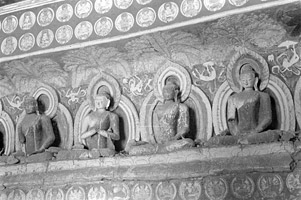

Concerning the caves of Mang-nang (Figs. 1-2), a site which the Italian scholar explored from the 15th to the 17th August 1935 and to whose wall paintings in Indian style he devoted an article, he wrote: "We walk on heaps of manuscripts thrown at random one upon the other, by the hundreds, by the thousands, often even for a few metres of thickness."[15] He found an even worse situation in the caves of Dung-dkar (Fig. 3), a site which he visited on the 25th August 1935, and where he lost his temper:

"In the whole kingdom of Guge, Tsaparang was perhaps the most densely inhabited place. The usual dwellings excavated in the rock and the cells of hermits open in its steep faces, the usual ruins of castles and of temples at the top: but even here we face remains of great importance: paintings, stuccoes, manuscripts, statues of all sorts and ages stacked up in the shade of chapels: art treasures thrown higgledy-piggledy as useless junk by the few surviving monks. They have never seen a European: they open the doors of their holy sites unwillingly to me, but lower their heads in shame when the horrible confusion in which they keep these places makes me lose my patience. I cannot stand seeing a beautiful thing, a work of art thrown there like scrap; I cannot bear seeing century-old paintings — minutely painted with such devoted care by a school of artists for whom painting was a synonym for praying — creased, ragged, riddled with holes, those wooden statues brought perhaps from India by the first apostles of Buddhism, piled up one above the other, their heads and hands cut off: those books thrown into the darkest corners in a tangle from which it is almost impossible to disentangle and reassemble the volumes. And when these monks who no longer understand anything, who do not know the value of the things with whose custody they have been entrusted, pretend to be conscientious, they become really hateful to me.

A people who lived in their faith dwelled here, there were noble souls making themselves sublime in asceticism and contemplation, ecstatic in mystical exaltation; there were artists who knew how to create works worthy of standing comparison with the best ones in the East, pious kings under whose rule the country prospered and became refined. Now not only is all trace of life erased, not only does the desert with its sands and silence destroy the last works of man, but spiritual decadence clouds and grips the soul of the few survivors."[16]

Fig. 4Tucci found a totally different situation in dGe-lugs-pa monasteries, such as 'Bras-spung and Sera, that he visited in Central Tibet (dBus).[17]

Besides the scourge of time and neglect by local people, some Western Tibetan caves seem to have suffered also after the Cultural Revolution, in spite of the care shown by authorities in preserving the Tibetan cultural heritage, as shown by the case of the murals in the cave of dPal-dkar-po bSam-gtan, which Professor Huo Wei visited first in 2001 and then in July 2004, finding to his dismay that in the meantime sections of the paintings had been detached and stolen to satisfy the demand of the antiques market (Fig. 4).[18]

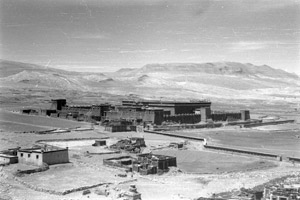

Fig. 5Also Tucci's view about the future of the monastery of Tsaparang (Tib. rTsa-brang, Fig. 5) was rather gloomy, though somehow conditioned by his Western antiquarian outlook: "The White Temple in Tsaparang already starts to lose its superb frescoes, cracked, effaced and fallen on the floor. The Changzod told me that if he had the means he would like to set them up again and have the paintings redone: that is the best fate to be expected for the monuments of ancient Tibetan art: if they do not collapse, a thick layer of lime and earth will cover the ancient frescoes which will be chipped to give grip to the new plaster; then one of the many very modest wandering artists will cover all with his clumsy figures with bright colors imported from Europe."[19]

On Western Tibetan temples in general the Italian scholar concludes:

"Before the ravages of time and men's neglect would efface the memory of a civilization bound entirely to death, I thought it was my duty of a man of science to return to those so inaccessible provinces, to save the most important documents from oblivion by the memory of their photographic records."[20]

The kind of situations that Tucci came across and in which he operated may be exemplified by his and Ghersi's visit to Toling (Tib. mTho-lding), dating back to the 11th century, as described in a report written for Indian authorities upon his return from the 1933 expedition, as quoted by Oscar Nalesini:

"Unfortunately neither the Lamas nor the None [Prince] of Spiti seem to realize the importance of the monuments that have been committed to them and of which they ought to take better care. I should like to invite the attention of the British Government to this fact and I do hope that some steps will be taken in order to preserve the frescoes on the walls and the very fine stucco-images (…). I hardly need to insist upon the immense importance of this large [collection of] photographic documents (…) which I could collect since it is well known that the monastery of Toling is one of the oldest, richest and finest of Tibet. These documents are of unrivalled interest for the religious history of Tibet as well as for the history of Indo-Tibetan Art (…). The rain dropping through the ceiling left unrepaired for years is washing away the marvelous frescoes (…). Unless the Tibetan Government does some urgent repairs, it will shortly be a ruin yet in no other part of Tibet is it ['is' in the text] possible to find finer ['finest' in the text] paintings and better workmanship. This is why here also I took photos of the interior of all temples and chapels so that if they are to tumble down western scholars might at least have an exact idea of what they were."[21]

In mTho-lding Tucci and Ghersi found many sheets of manuscripts and fragments of clay images as well as ruins and water seepages due to lack of care or abandonment, and eventually entered a cave already visited by the British captain G. Young and containing fragments of wood and clay images, pieces of large gilded copper mandorlas as well as a whole library of ancient Buddhist texts belonging to the Tibetan canonical collections and illustrated with superb miniatures probably fashioned by Indian artists who had been compelled to leave India after the Muslim conquest. Young, who explored West Tibet in 1919, took away secretly fragments of statues and books, which were then deposited in the Lahore Museum.[22] With Ghersi's help Tucci felt entitled to try to do the same, arguing that this was an academic duty since Tibetans did not care about their sacred monuments and the treasures they held, but watched unperturbed the ruin of precious material in which their ancestors had expressed their experiences symbolically or recorded the chronicles of their political life.[23]

The result was the acquisition of a number of objects, sometimes brought to the Italian scholar by monks and laymen during the night,[24] as described by Fosco Maraini,[25] sometimes obtained by stratagems, as in the case of an early Indian wooden image in the temple devoted to Rin-chen-bzang-po in the monastery of Lha-lung, in Spiti, which the Italian scholar told monks to have seen in a dream, whereupon a special tantric ceremony was performed involving an oracle, half a dozen monks, one with the role of village counsel arguing that the statue could not abandon the community it had protected for centuries, another defending the foreigner who had come with faith from distant countries and invoking the god's compassion upon him. The ceremony was repeated three times, and in the end the deity took possession of the oracle and started to talk through him uttering broken words in a falsetto voice. During the night the latter was compensated for his generosity.[26] It should be pointed out that even when acquisitions proved successful, their export might not prove so: on one occasion Tucci is reported to have torn to pieces a manuscript in front an Indian customs officer who may have regarded as insufficient the bakshish offered to him.[27]

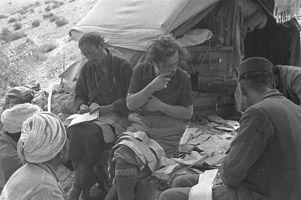

The Italian scholar continued that kind of activity in Southwest Tibet with the photographic assistance of Maraini, who describes also the former’s acquisition of religious items at rKyang-phu:

“(…) I hear vaguely Tucci and the monk’s voices in the nearby room. I hear the word gormo, rupees, being repeated again and again. Here is another among the infinite aspects of my versatile guru: now he is the skilled dealer of Tibetan antiquities in action! By now the scene is well known. Evening has fallen. In the dusk one may see barefoot monks passing by stealthily with their monstrous outlines. Do they suffer from a multiplication of arms, from immeasurable scrota, from dropsy at their backs? Not at all. They have large, fragile, rare, amazing treasures under their very greasy and filthy habits. They go there secretly, into the guru’s bedroom. After long bargaining (the master would not allow easily being taken for a ride) the art objects remain and the monks return to their impoverished monastery with handfuls (for them unheard of) of gormos.”[28]

Fig. 6Indeed Tucci acquired manuscripts (cf. Fig. 6)[29] as well as images as late as in the 1940s and on that subject Maraini, in spite of the fact that he could be frankly and openly critical of his master, writes:

“Tucci has been accused several times, by irresponsible rumors, of having taken away (through acquisitions, obviously) many, too many art treasures from Tibet. On that point I raise the loudest of voices in defense of the professor. Had he taken away more, many more, he would have saved them from the destructive and iconoclastic follies of the Chinese![30] In that respect I stand up for Sir Aurel Stein, for von Le Coq, for Paul Pelliot, for Jacques Bacot, for Edoardo Chiossone, for Ernesto Fenollosa, for Guimet and for all those other Europeans and Americans who have saved for mankind whole art treasures that were not appreciated by their owners and ran the risk of being lost or destroyed because of popular, political, religious movements of various kind. I believe that, also for our own art treasures, for instance, some dispersion in the world is a blessing: one never knows which disaster (earthquakes, fires, ideological follies) may hit them. That the Gioconda be in Paris and the Parthenon marbles be in London, are cases that should be blessed, rather than condemned”.[31]

Tucci’s most important discoveries occurred in Southwest Tibet, particularly in the monasteries of Sa-skya, Ngor and Zhwa-lu, in whose “neglected, unattended and dusty libraries” he found “almost seven thousand handwritten pages of Indian works that were believed to be lost.” In other words he “discovered the originals in Sanskrit, on palm leaves, of many of the most important philosophical and religious works of India” by authors including Nagârjuna, Vasubandhu, Dinnâga and many others whose works he brought to light on the shelves of Tibetan monasteries, and wondered what he should do with all those manuscripts, which had been photographed by captain Boffa.[32]

A special place is allotted to Sa-skya, which Tucci introduces as follows after his visit in 1939: "A still virgin place, both because Tibetans do not have the desire or ability to reconstruct their past and to cover again the stages of their culture, and because the few travelers who preceded me at Sakya in the last hundred years passed through it a bit too hurriedly. For instance, none has been able to give us a description of this place like that found in the diary of another Italian who passed through it in 1710, I mean Ippolito Desideri who in a few lines, with his brevity, draws a full and very lively picture of it."[33] In a later article of his specifically devoted to Sa-skya in the same periodical, mentioning again Desideri as the one who afforded the first description of that site, so precise and accurate that one could do no better even in his day,[34] Tucci explains both its rise and its decadence:

“By then sects had started to be formed; acquiring political importance, they consolidated their power building a number of monasteries in which monks turned into soldiers in case of need. The modest chapels of ancient hermits became sumptuous temples; beautifying and decorating them with munificent offers was an act of faith and political wisdom. The trade and relationship with China, Central Asia and India made the country prosperous as never again. In such favorable circumstances, Tibetan art was born indeed at Sakya”.[35] There “the monasteries, pulled down during century-old struggles with rival sects, burned during the Tartars’ invasions,[36] contained art treasures and more recent junk hoarded higgledy-piggledy, like huge junk shops. All speaks of decadence and impoverishment. On the right bank of the river the town and monasteries climb on the flank of the mountain, and rise like powerful terraces on which the golden spires and roofs of the temples shine in the sun.”[37]

Fig. 7At the time of his visit in 1939 Tucci reckoned that, comparing with the size of Tibetan villages in Southwest Tibet, Sakya was a “large center”, counting about five hundred houses and less than one thousand inhabitants, besides a dozen temples and about three thousand monks.[38] The Italian scholar adds: “The most ancient temples are in the middle of the village which grows around them almost to protect them (…). But now these temples are almost abandoned, storerooms rather than places of worship. Perhaps they are too many for all of them to receive regular services. All the religious life of the place takes place in the great temple in the valley”,[39] corresponding to the huge fortified monastery on the other side of the river (Fig. 7):

“The most solemn of the monasteries is the great Ducàn raising its towered mass to the left of the river: it looks like a fortress rather than like a temple, so massive and stern, with few windows and many loopholes. It seems to be built there to block the valley; it was raised when the Sakyas saw their power threatened by rival sects sending their armies of monks and mercenaries to appear on the overhanging passes.”[40]

Upon his arrival in Sa-skya Tucci paid his first visit to the abbot, who was married, and who received him wearing his Mongol costume and sitting on a high throne in his “pompous” private chapel, the gilded images of gods on the tall gilt shelves along two walls being “clumsy and badly finished, not comparable to the ancient ones heaped up on the altars of the temples”[41] in the main monastic building. By then the abbots had abandoned the majestic and solemn “four-tower palace” rising in the middle of the small town, preferring to live in their solitary “villas” in the countryside:

“They live as if estranged from the world in that palace of theirs, which looks like a prison; and through its half-closed windows they peek beyond it at what happens outside, along the roads, without having the courage to come down among the crowd and mix with it, and to know its joys and sorrows. They do not deal with earthly matters; the monastery is run by ministers and monks who are responsible for its discipline and administration; the people are in the hands of the ‘shapè’, namely lay officers, who act as they like and torment people at their leisure. But even the abbots are not serene (…). Now the princes of Sakya are two: the elder is on the throne and the other waits for the moment to succeed him, and meanwhile makes his [elder’s] life bitter through continuous plots and traps. Even in Tibet the ambition for power torments souls and diverts them from those serene beatitudes to which religion is meant to lead them. But hatred and spite do not burst into violent disputes; they smolder under genuflections and bows, they leak through the servants’ whispered chatter, they wind in gossip and slander. They are almost two parties clashing in a silent but implacable way under a ceremonious bigotry.

Pilgrims flocking to this holy place from every part of Tibet are unaware of those struggles and enmities blurring the peace of the divine abbots and breathe with moved simplicity that serene and quiet aura blowing gently over the holy land. They perform the ritual circumambulation around the temples prostrating themselves reverently at every step, chanting, listening with stunned devotion to the miracles and legends told and often invented for their edification by the guides. But even in this place you see that progressive decay corroding Tibet slowly, but fatally; it is a whole civilization that changes, or to say it better, crumbles, for there are no seeds and vital impulses that may survive in it as soon as more human and earthly aspirations succeed the religious ideal which has inspired it to this day. Losing their faith, leaving their beliefs, Tibetans find themselves on a sterile soil, on which it will be difficult that new germs may take root and prosper.”[42]

Tucci’s view extends to the contemporary production of traditional art at the same site:

“Life in Sakya is dominated by religion: the calendar records the holy feasts that give an unusual animation to the village and monastery. The bazar, usually insignificant, is enriched by improvised stalls on which pedlars spread out their junk purchased in India and resold at ten times more than their cost. You get the impression that Tibet is no longer able to produce anything; all comes from outside. Copper and silver artifacts have become barbarous: rough in their manufacture, and shoddy in that ornamentation which often beautifies ancient objects with baroque excess. Tibet has grown poor, but at the same time starts to feel the fascination of exotic items, which merchants and pilgrims introduce from distant places in India.”[43]

In that connection the Italian scholar mentions the Nepalese trading their own items, mostly womanly ornaments fashioned by Newar goldsmiths, but also aluminium and majolica items made in Japan.[44] Indeed the current sale of Nepalese religious paintings and items by Tibetan traders as far as rGyal-rong[45] represents the continuation and development of a trend that started long ago. Hugh Richardson raised the issue of the future of Tibetan material culture in relation to the isolation of Tibet during the period of Manchu overlordship in the following terms:

“A certain sterility is now apparent in Tibetan crafts, art-forms, literature, imagery and all the rest. But as the various things produced continue to be true to traditional form and always beautiful in themselves, one hesitates to make adverse comments on this score. But the question arises: what now becomes of Tibetan civilization? It is almost a general rule that when any culture becomes cut off from outside influences and ceases to develop new forms, it is already moribund. Is it possible that Tibetan Buddhist civilization was an exception? Although by the seventeenth century we already know almost its whole content, there seems no inherent reason why, left to itself, it should not have continued to live on as it lived until the mid-twentieth century. Good religious paintings in the accepted styles continued to be produced; books were still printed by the laborious but extremely skilful craft of carving wooden printing blocks; learned commentaries, mainly on philosopy and logic, were still written by masters for their pupils; texts and schools of teaching were analyzed; catalogues of deities, teachers, images and temples were drawn up; sacred places were described as pilgrims’ itineraries; new monasteries and temples were founded.”[46]

Giuseppe Tucci’s criticism concerning the preservation of ancient monuments in Southwest Tibet extends to other very important monastic centers, such as rGyal-rtse and Zhwa-lu, containing masterpieces of Tibetan art. As to the former he writes: “To be frank, the way these ancient monuments are kept is most lamentable. Neither the authorities nor the lamas have an idea of their great importance.”[47] As for the monastery of Zhwa-lu, which had close connections with the kingdom of rGyal-rtse, he comments: “Not all the pictures, but a large part of them are intact; I do not know for how long, as these monuments are entrusted to the care of an ignorant and increasingly impoverished community, so that there is no hope of their survival, unless they are properly and speedily repaired.”[48]

A special place is allotted to the small but important site of rKyang-phu (also rKyang-bu and sKyang), rising at about 4,100 m., one kilometre and a half west of the village of Sa-ma-mda’, on the trade route linking Sikkim to South Tibet. A temple had already been founded at that place in the latter half of the 8th century, during the rule of the Tibetan emperor Khri Srong-lde-brtsan, who had adopted Buddhism as state religion. The temples visited by Tucci had been raised by Chos-kyi-blo-gros, a Tibetan master who spent some time in Western Tibet, where he met the famous scholar and translator Rin-chen-bzan-po twice during the first half of the 11th century. The inscriptions engraved on stone blocks fixed on the inner side of the boundary wall included invocations to the dharmarāja Kun-dga’-rgyal-mtshan-dpal-bzang-po (1310-1358),[49] a grand lama of the Sa-skya religious order, to which the monastery had ended up belonging, who renovated and had it redecorated. In 1937 Tucci noticed that the entrance porch was used by villagers as a warehouse,[50] whereas some of the paintings were already ruined because of seepage of water through the roof.[51]

Maraini states that the monastery was in a “pitiful state of neglect, actually a complete ruin in most parts” except for the main temple.[52] There were “no longer lamas, ascetics, doctors, abbots”: “a family of good but rough farmers” held “in ruinous custody that place” and had “transformed it into a kind of convenient farm”. One could see around “hoes, ploughs, saddles, sieves, old guns, butter churns, ropes, bags, sacks, hides”, while “an elderly monk, dirty and indolent”, appeared somewhere. From his garment one could understand that he belonged to the dGe-lugs-pa order, “dominating on much of Tibet” and regarding such sanctuaries, “inherited so to speak” from the other religious orders, then in a subordinate position, as “stepchildren” and kept them “alive out of mere charity or perhaps, better, out of mere inertia.”[53] About thirty years after Tucci and Maraini’s visit to rKyang-phu, the Cultural Revolution, seen with sympathy by some Westerners, even in Italy,[54] reduced the monastery to a huge heap of rubble.

Fig. 8Another important temple site in South Tibet where Tucci noticed that important wall paintings were erased by water coming down from the roofs is Dratang (Grwa-thang; see Fig. 8),[55] where during renovation works in the 1940s further damage occurred when windows were opened through fine 11th-century murals.[56]

One of the conclusions drawn by Tucci in Indo-Tibetica on the state of Tibetan religious monuments in Southwest Tibet is that the dGe-lugs-pa order inherited the temples built by the schools that preceded it, but “has been been unable to build anything new and great”: “The monasteries in the areas that I visited and studied in this volume were once flourishing at the highest degree, but today they are found in a deplorable state of neglect and decadence; neglect because no one seems to care about them, and decadence because they no longer shed that light of thought and spiritual nobility for which they were renowned one day.”[57]

Although Tucci consistently criticizes people and institutions — including the Tibetan government — responsible for the upkeep of some of the most important monuments in West, Southwest and South Tibet in the 1930s and 1940s, it should be pointed out that a Buddhist canonical text such as the Kriyâsamgraha prescribes to throw images beyond repair into water or to burn them, or else to melt them down,[58] in spite of the fact that the restoration of religious images is known in the Indo-Tibetan world. Indeed, from a Buddhist point of view, such images are imperfect, while commissioning new ones is essential to accumulate merits, as it has been in Christian tradition, too. In fact restoration and conservation — in the modern, technical sense given to those terms — is a relatively recent phenomenon in Western cultural history: until about a century ago also in Europe ancient murals might be painted over or even destroyed in the course of the renovation of religious buildings.[59]

It is obvious that a compromise has to be found, reconciling traditional Buddhist attitudes with the necessity of preserving surviving monuments and religious images belonging to the world cultural heritage. A systematic way has to be devised in order to promote a new awareness of the importance of conservation in monasteries all over geo-cultural Tibet, while respecting — and furthermore studying — the contemporary production of traditional religious images. The local religious ought be made aware of their responsibility in maintaining the treasures under their custody with a new outlook, working out new educational strategies — by including the study of art history in the context of local history — and implementing them in monastic curricula.

I thank my wife, Stella Rigo Righi — who read some of the books quoted in this article even before I managed to do so — for her suggestions during the stimulating discussions we had on the subject.

Bibliography

Bianchi, Ester 2001. The Iron Statue Monastery. “Tiexiangsi", A Buddhist Nunnery of Tibetan Tradition in Contemporary China. Firenze: Leo S. Olschki.

— 2004. “The Tantric Rebirth Movement in Modern China. Esoteric Buddhism re-vivified by the Japanese and Tibetan Traditions.” Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungarica LVII: 31-54.

— 2008. “Protecting Beijing: The Tibetan Image of Yamāntaka-Vajrabhairava in Late Imperial and Republican China.” In Monica Esposito (ed.), Images of Tibet in the 19th and 20th Centuries, pp. 329-356. Paris: École française d’Extrême-Orient.

— 2014. “Xizang re 西 藏 熱 (“febbre per il Tibet”): il buddhismo tibetano tra i cinesi di oggi.” In Erberto Lo Bue (ed.), Tibet fra mito e realtà. Tibet between Myth and Reality, pp. 81-90. Firenze: Leo S. Olschki.

Desideri, Ippolito 1956. Relazione, Book II. In Luciano Petech (ed.), I missionari italiani nel Tibet e nel Nepal: Ippolito Desideri S.I., VI, pp. 1-108. Roma: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato - Libreria dello Stato.

Farrington, Anthony J. (ed.) 2002. British Intelligence on China in Tibet, 1903-1950. Formerly classified and confidential British intelligence and policy files, Leiden: IDC.

Garzilli, Enrica 2012. L’esploratore del Duce. Le avventure di Giuseppe Tucci e la politica italiana in Oriente da Mussolini a Andreotti. Con il carteggio di Giulio Andreotti, I. Roma – Milano: Memori – Asiatica Association.

Heller, Amy 2002. “The Paintings of Gra thang: History and Iconography of an 11th Century Tibetan Temple.” In Erberto Lo Bue (ed.), Contributions to the History of Tibetan Art, special issue of The Tibet Journal XXVII/1-2: 37-70.

Jones, Alison Denton 2011. “Contemporary Han Chinese Involvement in Tibetan Buddhism: A Case Study from Nanjing.” Social Compass 58/4: 540-553.

Kapstein, Matthew T. 2009. Buddhism Between Tibet and China. Boston: Wisdom Publications.

Klimburg-Salter, Deborah 2014. “When Tibet was Unknown: The Tucci Tibetan Expeditions (1926-48) and the Tucci Painting Collection.” Orientations 34/4: 42-53.

Lo Bue, Erberto 2006. “Problems of Conservation of Murals in Tibetan Temples.” In Xie Jisheng, Shen Weirong and Liao Yang (eds), Studies in Sino-Tibetan Buddhist Art. Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Tibetan Archaeology and Art, Beijing, September 3-6, 2004, pp. 404-426. Beijing: China Tibetology Publishing House.

— 2007 (a). “Giuseppe Tucci and Historical Studies on Tibetan Art.” The Tibet Journal XXXII/1: 53-64.

— 2007 (b) “Problems of Conservation and Appreciation of Tibetan Mural Painting.” In Francesca De Filippi (ed.), Restoration and Protection of Cultural Heritage in Historical Cities of Asia: between modernity and tradition, pp. 113-124. Roma: Politecnico di Torino - ASIA Onlus.

— 2008. “Tibetan Aesthetics versus Western Aesthetics in the Appreciation of Religious Art”, in Monica Esposito (ed.), Images of Tibet in the 19th and 20th Centuries, II, pp. 687-704. Paris: École française d’Extrême-Orient.

Maraini, Fosco 1998. Segreto Tibet. Firenze: Dall'Oglio.

Nalesini, Oscar 2013. “Onori e nefandezze di un esploratore. Note in margine a una recente biografia di Giuseppe Tucci.” Annali – Istituto Universitario Orientale 73: 201-275.

— 2014. “Pictures from a Legacy: The Tucci Photographic Archive.” Orientations 45/1: 54-66.

Petech, Luciano 1990. Central Tibet and the Mongols. The Yüan - Sa-skya Period of Tibetan History. Roma: IsMEO.

Pritzker, Thomas 1996. “A Preliminary Report on Early Cave Paintings of Western Tibet.” Orientations 27/6: 26-47.

Skorupski, Tadeusz (ed.) 2002. Kriyāsaµgraha. Compendium of Buddhist Rituals. An abridged version. Tring: Institute of Buddhist Studies.

Snellgrove, David L. and Hugh Richardson. A Cultural History of Tibet. Boulder: Shambhala 1995.

Tuttle, Gray 2004. Tibetan Buddhists in the Making of Modern China. New York: Columbia University Press.

Tucci, Giuseppe 1931 and 2005 repr. “Teorie ed esperienze dei mistici tibetani.” Il Progresso Religioso XI: 170-182. Reprinted with the title “Nirvana” in Il paese delle donne dai molti mariti, pp. 113-129. Venezia: Neri Pozza.

— 1933 and 2005 repr. “L’ultima mia spedizione sull’Imalaya.” Nuova Antologia 365: 245-258. Reprinted with the title “Himalaya” in Il paese delle donne dai molti mariti, pp. 19-34. Venezia: Neri Pozza.

— 1935 and 2005 repr. “Splendori di un mondo che scompare. Nel Tibet occidentale.” Le Vie d’Italia e del Mondo III/8: 911-937. Reprinted with the title “Splendori di un mondo che scompare” in Il paese delle donne dai molti mariti, pp. 47-56. Venezia: Neri Pozza.

— 1936 (a) and 2005 repr. “Il Kailasa, montagna sacra del Tibet”. Le Vie d’Italia e del Mondo IV: 753-772. Reprinted with the title “Il Kailasa” in Il paese delle donne dai molti mariti, pp. 275-283. Venezia: Neri Pozza.

— 1936 (b) and 2005 repr. “Il Manasarovar, lago sacro del Tibet.” Le Vie d’Italia e del Mondo IV: 253-270. Reprinted with the title “Acque cosmiche” in Il paese delle donne dai molti mariti, pp. 267-274. Venezia: Neri Pozza.

— 1937 and 1985 repr. Santi e briganti nel Tibet ignoto. Diario della spedizione nel Tibet occidentale 1935, Milano: Ulrico Hoepli. Reprinted with the title Tibet ignoto. Una spedizione fra santi e briganti nella millenaria terra del Dalai Lama. Roma: Newton Compton.

— 1938 and 2005 repr. “Berretti rossi e berretti gialli.” Asiatica IV (1938): 255-262. Reprinted in Il paese delle donne dai molti mariti, pp. 131-139. Venezia: Neri Pozza.

—1940 (a) and 2005 repr. “La mia spedizione in Tibet.” Asiatica VI: 1-13. Reprinted as “L’altare della terra” in Il paese delle donne dai molti mariti, pp. 63-74. Venezia: Neri Pozza.

— 1940 (b) and 2005 repr. “Un principato indipendente nel cuore del Tibet: Sachia.” Asiatica VI: 353-360. Reprinted as “Nel cuore del Tibet” in Il paese delle donne dai molti mariti, pp. 151-160.

— 1940 (c), 2005 repr. and 1971 (revised edition). “Nel Tibet centrale: relazione preliminare della spedizione 1939.” Bollettino della Reale Società Geografica Italiana LXXVII: 81-85. Partly reprinted as “Carovane” in Il paese delle donne dai molti mariti, pp. 57-62. Venezia: Neri Pozza. The latter is deprived of the last part of the original text and does not follow the complete and revised version published in Giuseppe Tucci, Opera Minora, II, pp. 363-368. Roma: Giovanni Bardi Editore.

—1941 (a). Tucci, Giuseppe, Indo-Tibetica. IV. Gyantse ed i suoi monasteri, I. Roma: Reale Accademia d'Italia.

— 1941 (b). Tucci, Giuseppe, Indo-Tibetica. IV. Gyantse ed i suoi monasteri, III. Roma: Reale Accademia d'Italia.

— 1952. A Lhasa e oltre. Diario della spedizione nel Tibet MCMXLVIII. Roma: La Libreria dello Stato.

— 1971 (a). "Indian paintings in Western Tibetan temples", in Opera Minora, II, pp. 357-362. Roma: Giovanni Bardi.

— 1971 (b). “Nel Tibet centrale: relazione preliminare della spedizione 1939”, in Opera Minora, II, pp. 363-368. Roma: Giovanni Bardi Editore. Revised version without illustrations of the article published in Bollettino della Reale Società Geografica Italiana LXXVII: 81-85.

— 1980. Tibetan Painted Scrolls, 2 vols. Kyoto: Rinsen Book Co.

— 2005. Il paese delle donne dai molti mariti. Venezia: Neri Pozza.

— and Eugenio Ghersi 1934. Cronaca della Missione scientifica Tucci nel Tibet Occidentale (1933). Roma: Reale Accademia d’Italia.

Wang-Toutain, Françoise 2000. “Quand les maîtres chinois s’éveillent au bouddhisme tibétain. Fazun: le Xuanzang des temps modernes.” Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 87/2: 707-727.

Young, G. 1919. “A Journey to Toling and Tsaparang in Western Tibet.” Journal of the Panjab Historical Society VII/2: 177-199.

Yü, Dan Smyer 2012. The Spread of Tibetan Buddhism in China. Charisma, Money, Enlightenment. London and New York: Routledge.

1. I wish to credit the support of the Rubin Museum of Art for writing this article originally meant for the volume Unveiling Buddhism: The Legacy of Giuseppe Tucci to be published in conjunction with an exhibition bearing the same title to be shown at the same Museum. I thank Oscar Nalesini for making available for publication Figs 1-3 and 5-7 from the Tucci Photographic Archive kept at Museo Nazionale d'Arte Orientale “Giuseppe Tucci”, Rome.

2. Tucci’s criticism is dealt with briefly by E. Lo Bue 2007 (a), and mentioned also in E. Lo Bue 2006, pp. 421-423, and 2007 (b), pp. 119-120.

3. For this date cf. E. Garzilli 2012, p. 198. For a long review article of Garzilli's book see O. Nalesini 2013.

4. Cf. G. Tucci 2005, figs 11, where the editor describes the stupa of Ri-bo-che as a Tibetan “temple”, and 19, where he places the Nepalese town of “Baktapur” in Tibet. A more serious blunder is represented by the omission of the last section of Tucci’s “Nel Tibet centrale. Relazione preliminare della spedizione 1939”, containing crucially important information on that expedition, published under the title of “Carovane”.

5. Cf. E. Garzilli 2012, p. 143.

6. Cf. E. Garzilli 2012, pp. 196-197.

7. Tucci never fell into the traps of “Orientalism” with its imaginary and sensationalistic construction of Asian lands as exotic and spiritual worlds, mysterious and mystical, though actually mystified for the purpose of one’s own use and consumption, as exemplified by the myth of Shambhala. Such phenomenon has been common not only in the West — especially from the 19th-century —, but also in the Far East since the establishment of political connections between Tibet and China, where Tibetan lamas have enjoyed great prestige from the 13th century, particularly under the Yüan and Qing dynasties, but also under the Ming dynasty, during the Republican period before the advent of Communism and even later, after the end of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (see for example F. Wang-Toutain 2000, E. Bianchi 2001, 2004, 2008 and 2014, G. Tuttle 2004, M. Kapstein 2009, A. Denton Jones 2011, D. Smyer Yü 2012).

8. Initially Tucci justified the use of the term “Lamaism” (1933 and 2005, p. 22), which he later repudiated stating that “first of all one ought to stop making use of the word Lamaism that is used to designate the Tibetan religion” (1938 and 2005, p. 131).

9. G. Tucci 1931 and 2005, p. 116. In my translations from Italian into English of passages from so far untranslated Italian texts of Tucci's I have attempted to render his literary style, with its particular language, construction and punctuation, as faithfully as possible, at the cost of appearing awkward.

10. G. Tucci 1938 and 2005, pp. 132-134. In using the expression “Tibetan Buddhism” the Italian scholar warns that the latter should not be regarded “as a particular interpretation of Buddhism; surely there is a great difference between the Tibetan religion and the doctrine of primitive Buddhism, but the distance is much smaller, even insignificant, between Tibetan Buddhism and the esoteric Buddhism that held sway in medieval India” (G. Tucci 1938 and 2005, p. 131).

11. G. Tucci 1931 and 2005, p. 122.

12. G. Tucci 1936 (b) and 2005, p. 279.

13. G. Tucci 1937: 32, and 1985, p. 36.

14. G. Tucci 1935 and 2005, p. 52. Tucci uses the terms “bronze”, though the copper alloy generally used in Tibet to fashion images is brass, “fresco”, albeit the fresco technique is not used in Tibetan painting, and “stucco” where the term “clay” ought to be used with reference to Tibetan sculpture.

15. G. Tucci 1937, p. 160. I had a similar experience in the bKa’-’gyur chapel of the monastery of Zhwa-lu when I first visited it on August 7, 1987, but there the books had been deliberately pulled down from the shelves and many of them burned in 1966 by people from Zhwa-lu and other places according my informant at the site, the Zhwa-lu mkhan-po bsKal-bzang-rnam-rgyal, as recorded in my diary. On the Indian paintings at Mang-nang see in particular G. Tucci 1971 (a).

16. G. Tucci 1937, pp. 171-172, and 1985, p. 136. The caves were left in an even worse state following the Cultural Revolution (cf. Pritzker 1996: 34-35, fig. 17).

17. Cf. G. Tucci 1952, p. 88.

18. In his lecture “The Pala Style in Buddhist Cave Paintings in Western Tibet”, delivered at the Second International Conference on Tibetan Archaeology and Arts in Beijing in September 2004, Professor Huo Wei, archaeologist, dean at the University of Sichuan and director of the Sichuan Museum, who had worked in west Tibet for the previous dozen years, showed images of recently discovered pictures of Buddhist murals in the cave temples at dPal-dkar-po bSam-gtan, wherefrom rectangular patches with details of deities had been removed by thieves in the lapse of tree years. To discourage such destructions, collectors of Tibetan art as well as museum keepers ought to do their part and avoid purchasing wall paintings of dubious origin.

19. G. Tucci 1937, p. 167, and 1985, p. 132. On the narrow antiquarian outlook of Western art historians and collectors of non-Western art see E. Lo Bue 2008.

20. G. Tucci 1937, pp. IX-X.

21. O. Nalesini 2014: 56. The “Report by Professor Tucci on his travel to Western Tibet”, written for Indian authorities and kept in the archive of the Government of India at the British Library, Foreign Department, Political External Collections, 1931-1950, was published by A. Farrington 2002, pp. 81 and 83. Cf. O. Nalesini 2013: 241.

22. Cf. E. Garzilli 2012, pp. 548-551, and G. Young 1919, p. 194.

23. Cf. G. Tucci 1937, p. 167, and 1985, p. 132, G. Tucci and E. Ghersi 1934, p. 310, and E. Garzilli 2012, p. 551.

24. Cf. E. Garzilli 2012, p. 524.

25. F. Maraini 1998, pp. 226 and 228.

26. Cf. G. Tucci and E. Ghersi 1934, pp. 101-107, and E. Garzilli 2012, pp. 526-529.

27. E. Garzilli 2012, p. 530.

28. Cf. F. Maraini 1998, pp. 226 and 228.

29. A similar photograph was published by E. Garzilli 2012, p. 490, fig. 17.

30. F. Maraini 1998, p. 228. Maraini’s identification of the Red Guards with the Chinese people is inaccurate and unfair, since also the latter had to suffer from that major disaster, worse than the military occupation of Tibet, which devastated China during those “years of fire and of shit between 1966 and 1967, when the whirl of the so-called ‘cultural revolution’” had broken out “in China and its colonies out of the insane will of the paranoid Mao”, and on the newly-built road between rGyal-rtse and Phag-ri, in South Tibet, “one could see lorries packed with shouting louts, equipped with red flags, with machine-guns, guns, shovels and pickaxes”, who, “one is almost ashamed to say, […] it seems to be ascertained were largely Tibetan youngsters […] guided […] by few Chinese adults” (F. Maraini 1998, p. 250).

31. F. Maraini 1998, pp. 226 and 228.

32. G. Tucci 1940 (a) and 2005, p. 68. Indeed the Indian manuscripts found by Tucci were scores; cf. G. Tucci 1940 (b), pp. 356 and 359, and 2005, p. 157.

33. G. Tucci 1940 (a) and 2005, p. 65. Cf. I. Desideri 1956, p. 21.

34. Cf. G. Tucci 1940 (b), p. 354, and 2005, p. 153.

35. G. Tucci 1940 (b), p. 359, and 2005, pp. 158-159. Cf. Tucci 1940 (b), p. 359, and 2005, p. 158, where he contrasts the situation in his days with the times in which the flourishing of Sa-skya coincided with one of the most prolific periods in the history of Tibetan art: “Yet one day Sakya was one of the greatest artistic centers in Tibet; the continuous relations with India and China educated its abbots to a lively love for art works. Flourishing schools of painting grew in these places under their encouragement and sponsorship; having soon freed themselves of their subjection to Indian and Chinese models, they created that Tibetan art which, in spite of showing always traces of its origins, acquired a very peculiar character of its own.”

36. Cf. G. Tucci 1940 (b), p. 354, and 2005, p. 153. Here Tucci expresses himself in rather approximate terms, though it is true that the rivalry between the monasteries of ’Bri-gung and Sa-skya turned into war. The latter submitted to the Mongols, whom Tucci calls here “Tartars”, and was protected by the emperor of China, Qubilai Khan, who established his rule over Tibet in a relationship between lay ruler and lama understood in Tibetan terms as “donor” versus “preceptor” (yon-mchod). In 1285 the monks of ’Bri-gung destroyed the monastery of Bya-yul and killed its abbot, a civil war started two years later (L. Petech 1990, p. 29), and in 1290 a Mongol army led by a Sa-skya general attacked, sacked and burned the monastery of ’Bri-gung, killing many of its soldier monks. That monastery was rebuilt, destroyed a second time during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution and rebuilt again in 1983.

37. G. Tucci 1940 (b), p. 354, and 2005, p. 153. Here I have chosen to translate Tucci’s inaccurate “cupole (…) delle pagode” as “roofs of the temples”.

38. Cf. G. Tucci 1940 (b), pp. 354 and 356, and 2005, pp. 152 and 156. Tucci speaks of “temples” (“templi”), though “monasteries” or “convents” (“conventi”, the term he generally uses for “monasteri”) would be more appropriate.

39. G. Tucci 1940 (b), p. 359, and 2005, p. 157.

40. G. Tucci 1940 (b), p. 356, and 2005, p. 157.

41. Cf. G. Tucci 1940 (b), p. 355, and 2005, pp. 154 and 155.

42. G. Tucci 1940 (b), p. 360, and 2005, pp. 159-160.

43. G. Tucci 1940 (b), p. 359, and 2005, p. 158.

44. Cf. G. Tucci, 1971 (b), p. 366 and 2005, p. 61, and 1940 (b), p. 353 and 2005, p.151.

45. Letter of Veronika Ronge dated February 14, 2014.

46. D. L. Snellgrove and H. Richardson 1995: 230-231.

47. G. Tucci 1941 (a), p. 7.

48. G. Tucci 1980, p. 177.

49. G. Tucci 1941 (a), p. 94.

50. G. Tucci 1941 (a), p. 98.

51. G. Tucci 1941 (b), fig. 12.

52. F. Maraini 1998, pp. 188-189.

53. F. Maraini 1998, p. 191.

54. In the 1960s an Italian factory worker having no experience in China or knowledge of the Chinese language became the leader of a pro-Maoist political organization and the director of its weekly, Servire il Popolo; in the 1980s he shifted to the Catholic movement “Comunione e Liberazione”, and eventually joined “Forza Italia” and “Popolo delle Libertà”, the two parties so far founded by Silvio Berlusconi. Similarly many of the staunchest Italian supporters of religious rule in Tibet come from the ranks of extreme “left-wing” — though often middle-class — students’ movements.

55. G. Tucci 1952, p. 126.

56. A. Heller 2002, pp. 42 and 63, fig. 12b.

57. G. Tucci 1941 (a), p. 39.

58. T. Skorupski 2002, p. 172.

59. The artistic cultural heritage in Italy — the country having the highest density of art historical monuments in the world — suffered at the hands not only of invaders, but also of local rulers — including Popes — until at least the second half of the 19th century. A witticism in Latin, which may be translated as “What barbarians did not do, the Barberinis did”, well exemplifies the situation of conservation in the Papal State — roughly corresponding to the present regions of Romagna, Marches, Umbria and Latium —, where aristocratic families such as the Barberinis did not hesitate to plunder or dismantle ancient monuments, for instance using the Colosseum as a quarry. The situation changed after the end of the Popes’ theocratic government in 1870 and the annexation of the Papal State to the secular Italian kingdom, newly unified and ruled by the house of Savoy. Many of the Catholic Church endowments having passed under the control of the Italian State, the latter entrusted Senator Adolfo Venturi with the huge task of carrying out an inventory with a photographic survey of the entire Italian artistic heritage.

asianart.com | articles