asianart.com | articles

Articles by Stephen Markel

Download the PDF version of this article

© Stephen Markel

April 02, 2025

(click on the image for full screen image with captions.)

Much has been written about the nature of copying in Mughal painting and drawing.[2] This essay will focus on two Mughal reinterpretations of a Flemish print. As Barbara Schmitz theorizes in the above quote, Mughal artists often responded to the European prints they encountered by reinterpreting the images through a Mughal lens with selective changes in figural style and composition [as well as proportion and perspective]. Important identifications of European prints re-envisioned in Mughal art were seminally recognized by Milo Cleveland Beach,[3] and later principally by Gauvin Alexander Bailey,[4] Gregory Minissale,[5] and S. P. Verma.[6]European painting was an important stimulus to later Mughal painting, as it was in the beginning, and in Akbar’s reign [1556-1605]. Mughal artists were adopting and adapting features from several European schools of landscape painting by the mid-18th century. … The best Mughal artists do not appear to be “copying” European figures per se, but they seem to be fascinated by form and movement that they observed, probably first in European art, then in the world around them. [1]

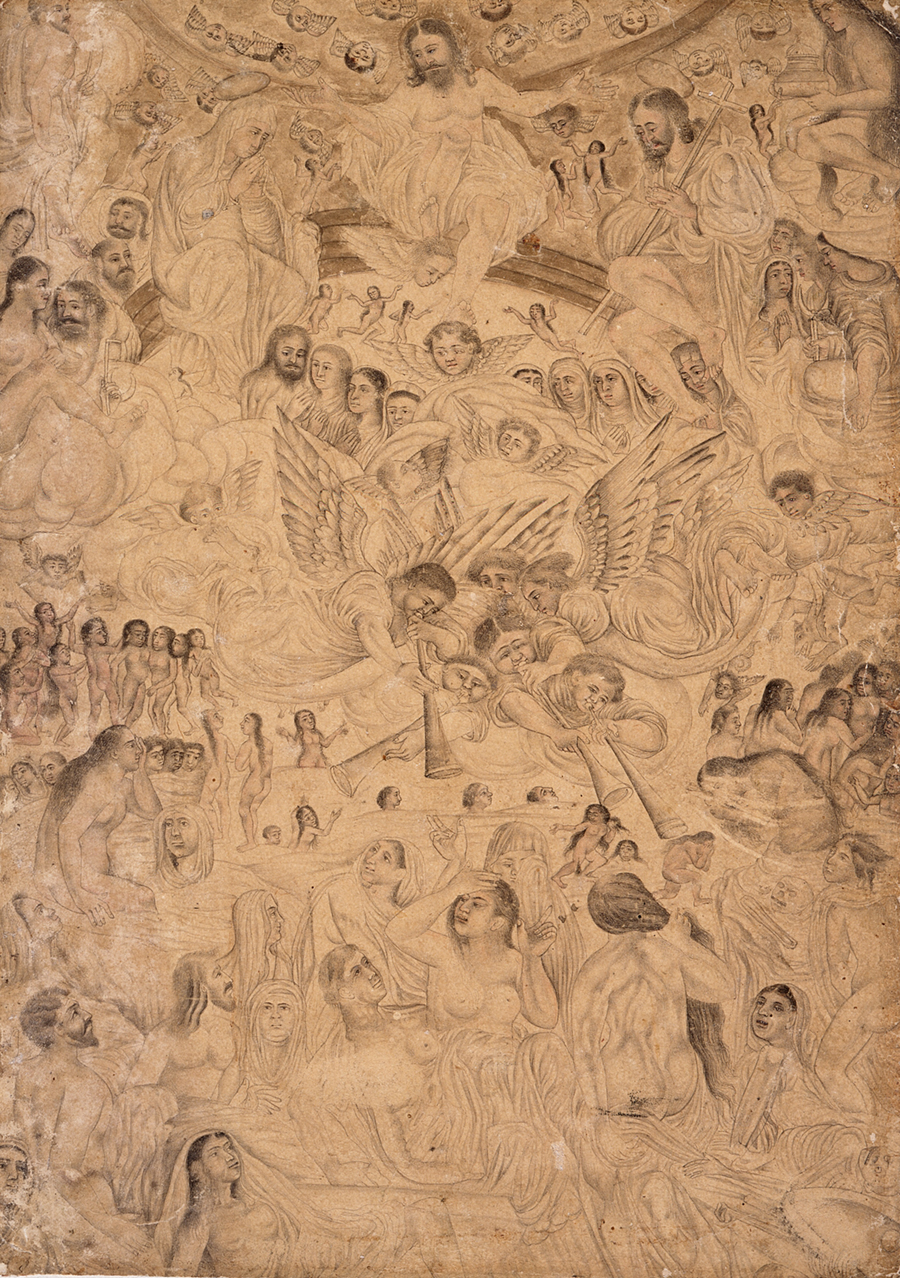

Fig. 1. The Last Judgment, drawing, mid-18th century, LACMA, M.75.113.4 |

The LACMA drawing was published in an exhibition catalogue by Pratapaditya Pal and Catherine Glynn [Benkaim], The Sensuous Line: Indian Drawings from the Paul F. Walter Collection (LACMA, 1976). It was specifically identified as the Resurrection of the Dead rather than The Last Judgment. It is actually both scenes, as the two related eschatological events are represented in the bottom and top halves of the drawing, respectively. According to Christian doctrine, The Last Judgment will occur at the end of the present era when there will be a Resurrection of the Dead of all mankind. The living and the dead will be judged by their charitable deeds and consigned consequently to heaven or hell. There are numerous scriptural references, but the principal authority is Christ’s discourse to his disciples in Matthew (25:31-46).

The LACMA catalogue entry also states that the drawing is “an adaptation of an original drawing that was itself a copy of a ceiling, as is evident from the upper sections of the composition.”[8] This assumption cannot be validated, as it is now known that the LACMA drawing is based closely on a print of The Last Judgment designed by Johannes Stradanus (née Jan van der Straet and known also as Giovanni Stradano, etc., 1523-1605).[9] Stradanus was a preeminent and prolific international artist.[10] He was a Flemish painter and print designer active mainly in Antwerp, Venice with Vasari (1511-1574), and at the Medici Court in Florence where he arrived in 1550. The Last Judgment was engraved in circa 1580 or circa 1590 by the Flemish printmaker Adriaen Collaert (1560-1618).[11] Prints designed by Stradanus and copies of them were widely circulated, so it is not surprising that at least one made its way to India.[12]

Fig. 2.The Last Judgment, Collaert engraving, c. 1590, Art Institute of Chicago, 2023.1068 |

The Collaert engraving is also distinguished by its prominent Latin inscriptions in the footer and on the cover of the tomb in the lower right corner. As might be expected, these are omitted in the LACMA drawing. The inscriptions and translations in the footer are as follows:

ECCI DIES DOMINI VENIET, CRVDELIS ET INDIGNATIONIS PLENVS, ET IRAE FVRORISQVE, AD PONENDAM TERRAM IN SOLITVDINEM, ET PECCATORES EIVS CONTERENDOS DE EA. ISA. XIII.The inscription and translation on the tomb cover are:

THERE WILL BE A HUNDRED DAYS OF THE LORD, FULL OF WRATH AND INDIGNATION, AND FIERCE WRATH, TO PLACE THE EARTH IN DESOLATION, AND TO DESTROY ITS SINNERS FROM IT. ISAIAH XIII.

Doctrina et pietate reverendo Patri F. Henrico Sedulio, Ordinis Mionorum regularis obfervantiae Guardiano Antverpiano, bonarum artium elegantiariumque moecenati, Hadrianus Collartus humillime Dedicabat.

To the venerable Father F. Henrico Sedulio [Henricus Sedulius (1547-1621)], Guardian of the Order of Friars Minor Regular of Antwerp, a scholar and elegant monk of the fine arts, Hadrianus Collartus most humbly dedicated his teachings and piety.

Ioann. Stradanus invent. / Adrian Collaert Sculp. et excud.

Johannes Stradanus invented / Adrian Collaert sculpted and printed

(All translations by Google Translate.)

Fig. 3.The Last Judgment, Stradanus, sketch, circa 1590, Cooper Hewitt, 1901-39-117 |

Fig. 4. The Last Judgment, painting, circa 1605-10, Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 1005032.d |

Like the LACMA drawing, the Mughal painting was not simply traced or copied directly from the Collaert engraving:

The figures are fewer in number, of a slightly altered scale, and hyper-masculine musculature is here replaced with a far softer, smoother treatment of form…. Other alterations are more artistic in nature: instead of the monochrome of the engraving, the Mughal artists use contrasting shades of colour – bright pigments for the believers and shadowy tones for the disbelievers – for symbolic effect. The faces of Mary and Jesus and certain areas of drapery are more worked up than other areas of the painting and are reminiscent of other works by the artist Manohar.[20]The gender changes observed in the LACMA drawing are also found sporadically in the Mughal painting. One major figure was converted (lower center, seated male figure emerging from the tomb, now rendered as a female seated in the edge of a pit), and the small robe-covered heads of the gender-neutral dead have all been reinterpreted as female.

Most of the iconographic attributes identifying the Christian figures in the Collaert engraving have been retained in the Mughal painting. These include such primary attributes as Cupid’s bow and arrow, but also the barely distinguishable attribute of the triangle of light above Christ’s head that presumably represents the Holy Trinity, signifying the oneness of God as Father, Son (Jesus Christ), and the Holy Spirit. In the LACMA drawing, the triangle is absent. A critical attribute in the Collaert engraving that is notably omitted from the Mughal painting is the reed Cross of St John the Baptist. Its purposeful omission is explained by Emily Hannam in the Royal Collection catalogue’s entry on the basis that the Cross is “a symbol of the Resurrection (eschewed in Muslim faith).”[21] The Cross is, however, depicted in the LACMA drawing. Its inclusion is significant for proving that the LAMCA drawing was based directly on the Collaert engraving rather than on the Mughal painting serving as an intermediary source. Additional confirming variances can be observed upon close examination. For example, note the winged putti head below St John the Baptist that is in both the Collaert engraving and the LACMA drawing, but is absent in the Mughal painting.

The Mughal painting was among the first paintings executed in the royal atelier of Emperor Jahangir (r. 1605-27) after his accession.[22] It was added to the Herat Khamsa of 1492 when it was refurbished with new Mughal paintings in circa 1605-10 that serve as commentaries on the manuscript’s themes.[23] Jahangir considered the Herat Khamsa the “finest turki (Chagatay Turkish) manuscript in his collection.”[24] Jahangir’s appropriation and adaption of Christian iconographic imagery are well known.[25] For example, see such important works as The Virgin Mary with the Christ Child above, Folio from the Salim Album, Allahabad, circa 1595-1600, and Jahangir and Jesus, Folio from the Minto Album, by Hashim, circa 1620, and Abu’l-Hasan, circa 1610-20, both in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin (44.6 and 7A.12, respectively);[26] and Jahangir Holding the Picture of Madonna, circa 1620, in the National Museum, New Delhi (55.58/31). Given Jahangir’s early predilection for Christian imagery, the Mughal painting of The Last Judgment likely appealed to the emperor because of its representation of Christ’s spiritual sovereignty and pictorial majesty. Both of Jahangir’s primary ideological interests of being “legitimatized as ruler of two worlds – the visible (‘alam-i suri) and the spiritual one (‘alam-i ma’nawi)”[27] are compellingly conveyed by the Mughal painting of The Last Judgment. This dual emphasis may also help explain why numerous minor figures in the Collaert engraving were omitted in the Mughal painting, thus increasing its visual clarity and potency, and why the Christian saints are retained and clearly identified by their iconography, thus establishing the spiritual legitimacy of the Mughal painting. Accordingly, I would characterize this conscious selective process as one in which the image was Mughalized, or as Ebba Koch terms it, an “interpretatio Mongolica” [Mongolian interpretation] with the European model’s “content and meaning … translated into the pictorial language of the Mughals.”[28]

In contrast, the LACMA drawing is a vortex of interconnected forms in a flattened perspective. It presents a fascination for studies of the human body, especially animated figural poses. With its conversion of numerous figures into representations of Indian women, it represents a process in which the image was Indianized with unfamiliar characters (anguished corpses and Christian saints) translated into a popular genre of familiarity (Indian courtly women). There is an evolution from a political and religious artistic response to a more purely artistic response that embodies its era. It becomes less of a symbolic imperial image and more of an artistic endeavor envisioning a more contemporaneous emphasis and greater intimacy in Indian imagery.

Stephen Markel, Ph.D., is the Senior Research Curator of South and Southeast Asian Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Footnotes

1. Barbara Schmitz, “After the Great Mughals,” in After the Great Mughals, ed. Barbara Schmitz (Mumbai: Marg Publications, 2002): 10.

2. For learned discussions of European prints copied in Mughal art, see Edward Maclagan, “The Missions and Mogul Painting,” in The Jesuits and the Great Mogul (London: Burns Oates and Washbourne, 1932): 222-267; Sanjay Subrahmanyam, “A Roomful of Mirrors: The Artful Embrace of Mughals and Franks, 1550-1700,” Ars Orientalis 39 (2010): 39-83; Ursula Weekes, “Rethinking the Historiography of Imperial Mughal Painting and its Encounters with Europe,” in Indian Art History: Changing Perspectives, ed. Parul Pandya Dhar (New Delhi: National Museum Institute and D.K. Printworld, 2011): 169-182; Ebba Koch, “Being like Jesus and Mary: The Jesuits, the Polyglot Bible and other Antwerp Print Works at the Mughal Court,” in Transcultural Imaginations of the Sacred, eds. Klaus Krüger and Margit Kern (Berlin: De Gruyter Brill and Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 2019): 197–230; and Alberto Saviello, “Inter-pictorial Religious Discourse in Mughal Paintings: Translations and Interpretations of Marian Images,” The Journal of Transcultural Studies 13:1-2 (2022): 32-55. For an analysis of Indian and European portrait copies, see Holly Shaffer, “Portraits and Types: Reinscribing Forms in Nineteenth-Century India and Europe,” Ars Orientalis 51 (2021): 249-285. For 18th- and 19th-century Mughal copies of 17th-century Mughal paintings, see Vishakha N. Desai, “Reflections of the Past in the Present: Copying Processes in Indian Painting,” in Perceptions of South Asia’s Visual Past, eds. Catherine B. Asher and Thomas R. Metcalf (New Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies, Madras, Swadharma Swarajya Sangha, and New Delhi: Oxford & IBH Pub. Co.,1994): 135-147; Robert J. Del Bontà, “Late or Faux Mughal Painting: A Question of Intent,” in After the Great Mughals, ed. Barbara Schmitz (Mumbai: Marg Publications, 2002): 150-165; and Yael Rice, “Painters, Albums, and Pandits: Agents of Image Reproduction in Early Modern South Asia,” Ars Orientalis 51 (2021): 27-64. In addition, portable sculptures may have also played a role in transmitting images, as a relatively unexplored Christian iconographic source adapted for Mughal painting may be found in Goan rock crystal and ivory sculptures. One example may be the sculpted images of the Christ Child as Savior of the World in relation to a Mughal painting attributed to 1622-23 of Jahangir Holding a Globe in the National Museum of Asian Art, Washington (F1948.28), https://asia.si.edu/explore-art-culture/collections/search/edanmdm:fsg_F1948.28/ (Accessed March 5, 2025.) See Nuno Vassallo e Silva, “Gold, Ivory, Crystal and Jade. Precious Objects from Goa and Ceylon,” in The Heritage of Rauluchantin (Lisbon: Museu de São Roque, 1996): 177, fig. 3; and Lucila Morais Santos, Arte do marfim: do Sagrado e da História na Coleção Souza Lima do Museu Histórico Nacional (Rio de Janeiro: Centro Cultural Banco do Brazil – Museu, 1993): 67, no. 210. For a comparable Philippine ivory representation, see Regalado Trota Jose, Images of Faith: Religious Ivory Carvings from the Philippines (Pasadena: Pacific Asia Museum, 1990): 55 (bottom illustration).

3. “The Gulshan Album and Its European Sources,” Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 63:332 (1965): 63-91; “A European Source for Early Mughal Painting,” Oriental Art (n.s.) 22:2 (Summer 1976): 180-188; “The Mughal Painter Kesu Das,” Archives of Asian Art 30 (1976-77): 34-52; The Grand Mughal: Imperial Painting in India 1600-1660 (Williamstown, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 1978); and “The Mughal Painter Abu'l Hasan and Some English Sources for his Style,” Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 38 (1980): 6-33.

4. The Jesuits and the Grand Mogul: Renaissance Art at the Imperial Court of India, 1580-1630 (Washington: Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Occasional Papers, vol. 2, 1998); “The Indian Conquest of Catholic Art: The Mughals, the Jesuits, and Imperial Mural Painting,” Art Journal 57:1 (Spring 1998): 24-30; Art on the Jesuit Missions in Asia and Latin America, 1542-1773 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999); and “Between Religions: Christianity in a Muslim Empire,” in Goa and the Great Mughal, eds. Jorge Flores and Nuno Vassallo e Silva (Lisbon: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 2004): 148-161.

5. “The Synthesis of European and Mughal Art in the Emperor Akbar’s Khamsa of Nizami,” Asianart.com (October 2000), https://www.asianart.com/articles/minissale/ (Accessed March 5, 2025.)

6. Crossing Cultural Frontiers: Biblical Themes in Mughal Painting (New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2011).

7. The as yet earliest known recorded provenance of the LACMA drawing (M.75.113.4) is the Kevorkian Foundation, founded by the Armenian-American New York art dealer Hagop Kevorkian (1872-1962). It was sold at auction in Highly Important Oriental Manuscripts and Miniatures: The Property of the Kevorkian Foundation, Sotheby’s, London, December 7, 1970, auction catalogue, p. 55, lot 135. Therein it was identified as The Last Judgment with “God the Father seated above with Christ and the Virgin Mary on either side of him.” The drawing was donated to LACMA in 1975 by the New York art collector Paul F. Walter (1935-2017).

8. Pratapaditya Pal and Catherine Glynn, The Sensuous Line: Indian Drawings from the Paul F. Walter Collection (Los Angeles: LACMA, 1976): 13, no. 4.

9. Jan van der Straet was known by some twenty different names. See the Getty Union List of Artist Names, https://www.getty.edu/vow/ULANServlet?english=Y&find=stradanus&role=&page=1&nation= (Accessed March 6, 2025.)

10. Gunther Thiem, “Studien zu Jan van der Straet, genannt Stradanus,” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 8:2 (September 1958): 88-111; Alessandra Baroni Vannucci, Jan van der Straet, detto Giovanni Stradano, flandrus pictor et inventor (Milan: Jandi Sapi Editori, 1997): and Alessandra Baroni and Manfred Sellink, Stradanus (1523-1605), Court Artist of the Medici (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2012).

11. F. W. H. Hollstein, The New Hollstein: Dutch and Flemish etchings, engravings and woodcuts 1450-1700: The Collaert Dynasty, Part II (Ouderkerk aan den Ijssel: Sound & Vision Publishers in cooperation with the Rijksprentenkabinet, Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2005): 189-190, no. 397/1. The Collaert engraving was independently discovered as the source for the LACMA drawing in 2022 during my research for its Curator Note in LACMA’s Collections Online, https://collections.lacma.org/node/241241. (Accessed March 7, 2025.) This was before I became aware of the Royal Collection’s excellent catalogue entry published in 2018 with the same discovery. See note 16.

12. Marjolein Leesberg, “Between Copy and Piracy,” in Baroni and Sellink, Stradanus (1523-1605): 161-182.

13. The Collaert engraving illustrated herein is in the Art Institute of Chicago (2023.1068). Additional impressions are in the Albertina Museum, Vienna (H/I/23/136), British Museum, London (1868,0612.432), Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam (BdH Boek FA 53 10426 (PK)), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (RP-P-1982-305), and Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels (S.II.10953).

14. http://cprhw.tt/o/2AP4R/. (Accessed March 7, 2025.) I would like to thank my colleague Claire Spadafora Baes, PhD, Wallis Annenberg Curatorial Fellow, Department of Prints & Drawings, LACMA, for informing me about this preliminary sketch and generously providing essential information on Stradanus and the Collaert engraving.

15. Jamie Kwan, “From Idea to Engraving: Stradanus and the Printmaking Process, https://www.cooperhewitt.org/2025/01/22/from-idea-to-engraving-stradanus-and-the-printmaking-process/ (Accessed March 7, 2025.)

16. Emily Hannam, Eastern Encounters: Four Centuries of Paintings and Manuscripts from the Indian Subcontinent (London: Royal Collection Trust, 2018): 102-103, no. 23; https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/2/collection/1005032-d/yawm-al-din-ywm-ldynlrm-the-day-of-judgement (Accessed March 11, 2025.) When previously published, the Mughal painting was said to be based on a “European painting” in Jeremiah P. Losty, The Art of the Book in India (London: The British Library, 1982): 96, no. 77; and as a “pastiche painting… adapted from more than one or two European prints/engravings (whereabouts not clear)” in Verma, Crossing Cultural Frontiers (2011): 58.

17. “amal-e nanha u manohar. Work of Nanha and Manohar.” Hannam, Eastern Encounters (2018), p. 102. A slightly alternative transliteration, “amal-e nanha wa manohar. Work of Nanha and Manohar,” is given in John Seyller, “Manohar,” in Masters of Indian Painting: 1100-1650, eds. Milo C. Beach, Eberhard Fischer, and B. N. Goswamy (Zurich: Museum Rietberg and Artibus Asiae Publishers, Supplementum 48 I/II, 2011): 1:137, no. 10.

18. The manuscript was presented by the Nawab of Oudh, Saadat Ali Khan (r. 1798-1814) to King George III (r. 1760-1820) by Lord Teignmouth, Governor-General of India (1793-98) in circa 1798.

19. Hannam, Eastern Encounters (2018): 242, note 79. The same note references the LACMA drawing and describes it as “a freehand drawing containing many elements of the engraving.”

20. Hannam, Eastern Encounters (2018): 102, no. 23.

21. Hannam, Eastern Encounters (2018): 102, no. 23.

22. Losty, The Art of the Book in India (1982): 96, no. 77.

23. The new Mughal painting of The Last Judgment may have been included as a counterpoint to the only original 16th-century Bukhara painting remaining in the manuscript, The Day of Judgment is Discussed in a Bathhouse (RCIN 1005032.i). Hannam, Eastern Encounters (2018): 99, no. 21, and 100-101, no. 22.

24. Hannam, Eastern Encounters (2018): 98, no. 21.

25. Ebba Koch, “The Influence of the Jesuit Mission on Symbolic Representations of the Mughal Emperors,” in Islam in India: Studies and Commentaries, ed. Christian W. Troll (Delhi: Vikas Publishing, 1982): 14-29. See also Glenn D. Lowry, “The Emperor Jahangir and the Iconography of the Divine in Mughal Painting,” The Rutgers Art Review 4 (January 1983): 36-45; Robert Skelton, “Imperial Symbolism in Mughal Painting,” in Content and Context of Visual Arts in the Islamic World, ed. Priscilla P. Soucek (University Park and London: Pennsylvania State University Press for the College Art Association of America, 1988): 177-87; and Jasper C. van Putten, “Jahangir Heroically Killing Poverty: Pictorial Sources and Pictorial Tradition in Mughal Allegory and Portraiture,” in The Meeting Place of British Middle East Studies: Emerging Scholars, Emergent Research & Approaches, eds. Amanda Phillips and Refqa Abu-Remaileh (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009): 101-20.

26. Linda York Leach, Mughal and Other Indian Paintings from the Chester Beatty Library, 2 vols. (London: Scorpion Cavendish, 1995), 1:304-305, no. 2.167 and 395-396, no. 3.22, respectively.

27. Koch, “The Influence of the Jesuit Mission,” (1982): 28.

28. Koch, “The Influence of the Jesuit Mission,” (1982): 20.