asianart.com

| articles

by

Julie Rauer

June 27, 2006

This article is based on and inspired

by an important exhibition of more than sixty intimate

paintings and drawings by Paul Klee in the Neue Galerie’s

exquisite exhibition, “Klee and America”,

Neue Galerie, New York NY, shown from March 9 through

May 22, 2006.

|

|

|

(click on the small image for full

screen image with captions.)

|

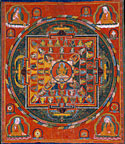

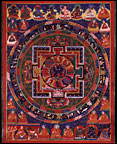

Avatar of the cosmos, omniscient and

fractured map of a lucid interior - the mandala - floating elements,

planetary eyes and mouth, that leap forwards and backwards in

time as wormholes to alternate existence, infinite dimensionality

projected with tripartite brush as spiritual architecture, art,

and ritual—Mandlebrot set of an inner psyche torn asunder,

rocked from equilibrium by the sound of contemplation turning

over irresolvable ontological issues inside a curious mind. Five

elements of relatively equal size comprising the template of a

whole universe—lunar and solar—structured around concentric

circles (‘khor) and squares sharing one center

(dkyil) which radiates spokes of enlightenment.

Fig. 1

|

|

In explicating the essence of Paul

Klee’s 1934 painting, The One Who Understands,

a disarmingly understated oil and gypsum masterwork of profound

reflection and metaphysical distillation, it is fitting that the

Swiss artist’s eastern connectivity, inclusiveness, and

visual construction comfortably share scholar Martin Brauen’s

definition of a mandala, dissected at length in his gratifyingly

comprehensive volume, The Mandala: Sacred Circle in Tibetan

Buddhism. [1]

Cosmogram, sacred realm, strongly symmetrical

diagram concentrated about a center and customarily sectioned

into four quadrants of equal size, catalyst for meditation, visualization,

and initiation, essential and ideal plan of a perfect universe,

“delineation of a consecrated superficies protected from

invasion by disintegrating forces symbolized in demoniacal cycle”

[2],

and the palace itself, home to the deities—all are mandalas—“as

are the deities themselves who reside in it, assembled in a clearly

ordered pattern. (fig. 1) The term ‘mandala’ can,

moreover, be applied to the whole cosmos, namely when the entire

purified universe is mentally offered in a special ritual”.

[3]

Fig. 2

|

|

| |

Fig. 3

|

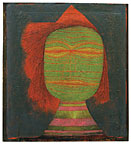

Discussing the term ‘mandala’,

Brauen also asserts its indication of “other structures…for

example the discs of the five elements that constitute the lower

part of the Kalacakra universe, or the discs of moon, sun and

the two planets Rāhu and Kālāgni that serve as

a throne for a diety.” [4]

Extrapolating to the cosmologically and spiritually diagrammatic

nature of another Klee painting, Actor’s Mask (Schauspieler=Maske),

(1924), [5]

which exerts a decidedly eastern partitioning of space, one can

again feel the verity of Brauen’s words (fig. 2). This painting

is one of more than sixty other intimate paintings and drawings

in the Neue Galerie’s exquisite exhibition, “Klee

and America”, displayed from March 9 through May 22, 2006

in New York City. Klee's painting eschews European artistic conventions,

as a work specifically Orientalist in thematic underpinning, cultural

influence, and chromatic treatment directly comparable, albeit

as marked abstraction versus ardent realism, to The Dahesh Museum’s

resplendent José Tapiró Baró painting, A

Tangerian Beauty (fig. 3).

In Klee’s facial strata of compressed

ocular and lingual tides, expansively linear cheeks and brow,

negative space captured and harvested into painful constriction,

and the perpetual act of drowning in ever deepening fathoms of

water while still on land, Actor’s Mask lifts this

visage out of any titular theatricality and into more intangible

realms. “…we shall discover that the human being is

also seen as a mandala. For instance each of the wind channels,

which according to Tantric conception flow inside the body, is

linked to a particular direction, element, aggregate (skandha),

and color, thereby forming a mandala. In the so-called ‘inner

mandala’, the human body is seen as a ‘cosmos mandala’…”

. [6]

Giuseppe Tucci, writing of strongly

analogous threads connecting the mandala to the human body in

The Theory and Practice of the Mandala, which specifically

investigates the modern psychology of the subconscious in relation

to Tibetan art and ritual practices, reiterates this precise correspondence

between microcosm and macrocosm, comparing the human body to the

universe as a whole, not only in its “physical extent and

divisions”, but further as container of all the Gods.

Fig. 4

|

|

Dissecting, reimagining, then reassembling

the human structure, reduced to the essential elements as mandalas,

Paul Klee (1879-1940) distilled the pathos of human existence,

the cyclical destruction and animation of form, intellect and

emotion strongly evident in the Neue Galerie’s Printed

Sheet with Picture (Bilderbogen), (1937), (fig. 4) which

presents a complex diagram of an individual’s universe,

or psychic life (which Tucci asserts reflects that of the universe

as the body mandala [7]),

in a maze of solar and lunar cycles, birth and death, deprivation

and satiation, intense scholarship and fanciful recreation, religion

and secular apparition. “On to the mandala was projected

the drama of cosmic disintegration and reintegration as relived

by the individual, sole contriver of his own salvation…”

[8].

From the grotesque, possibly stillborn, child to depthless matriarchal

grief , haunted domesticity sectioned into a cloven eye and arms

shorn of hands that serve only as labyrinthine walls, Klee’s

painting, a Mind mandala of ‘deep awareness’, speaks

of harrowing inner life with a distinctly eastern aesthetic.

| |

Fig. 5

|

True Orientalist from the earliest

years of his artistic life, Paul Klee profoundly altered his color

palette, compositional approach to space, graphic symbolism, and

dexterous architectural translation of three dimensions into two;

a fundamental visual iconography that would persist and metamorphose,

perpetually reinventing itself throughout his prolific, but tragically

abbreviated career [9].

This metamorphosis followed a 1914 trip to St. German (today Ez

Zahra) near Tunis with friends August Macke and Louis Moilliet.

(fig.5)

After traveling to Tunisia, Klee “reworked

the subject of a watercolor he had painted…consolidating

the essences of the compositional vocabulary he had developed

in the following year” [10],

finding lasting clarity and the foundation of his singular, highly

eclectic lexicon in North African subjects, light, decorative

motifs, and architecture.

Juxtaposing Klee’s Yellow

House (Gelbes Haus), (1915) (fig. 6) with The Dahesh Museum’s

Arabesques: Assembled Wooden Compartments and Borders

(1877) (fig. 7), a print by French Egyptologist Prisse d’Avennes,

striking analogies in the hallmark Klee “X” and arrow

symbols, densely crafted compartmentalization of space that would

come to dominate his oeuvre, and manipulation of color in service

of form, can be readily drawn.

In discussing the complex premises

from which the mandala derives, Tucci succinctly defines a structure

that perfectly describes Klee’s landscapes and cityscapes:

“It is a geometric projection of the world reduced to an

essential pattern”. [11]

While derisive observers have occasionally attempted to marginalize

Paul Klee’s meticulously constructed works as overly decorative,

they seem to have confused pattern with ornamentation; one is

a rigorous schematic exercise of intellect, while the other is

mere surface adornment.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 6 |

Fig. 7 |

Fig. 8 |

Fig. 9 |

Addressing patterns in the architecture

of iconic towns as mandalas, Brauen, in a key observation, connects

the morphology of urban forms with the universe itself, positing

their fundamental structure to be a reflection of the cosmos,

designed as its symbolic centers: “The architecture of many

towns mirrors an ever-recurring shape (gestalt) of the town, and

this shape of the town…mirrors an ever reappearing pattern,

the mandala.” (fig. 8 and fig. 9) [12]

In fact, “architectural precincts with a mandala-type or

cosmological structure are widespread in Asia” [13],

including: the towns of Kirtipur in the Kathmandu Valley and Leh

in Ladakh; the Mingtang, the Imperial Palace of pre-Buddhist China,

temple-towns of South India (the shrine of the chief deity at

the center of Tiruvanamalai). The ideal town plan of Bhaktapur

in the Kathmandu Valley “depicts a mandala with the shrine

of Tripurasundari in the middle”.

Middle Eastern cities, their gardens

and environs, inhabitants and trappings of exoticism—nectar

for European Orientalists—interpreted through Paul Klee’s

brilliant and intimate prism, abound in the chronology of the

painter’s advancing experimentation: Yellow House (1915),

Tunisian Gardens (1919), City in the Intermediate

Realm (1921), Gradation, Red-Green (Vermilion)

(1921), Cold City (1921) (fig. 10), Sketch in

the Manner of a Carpet (1923), Tropical Garden Plantation

(1923), Princess of Arabia (1924), and Oriental Pleasure

Garden (1925), Polyphonic Architecture (1930), Arabian

Song (1932)—ad infinitum.

Pointed arches, late antique Corinthian

columns, and bands of foliate decoration on the Mosque of Ahmad

Ibn Tulun, the oldest and largest original mosque in Cairo, subject

of Prisse d’Avennes’s, Mosque of Ahmad Ibn Tulun

(fig. 11), Arcade and Interior Windows (1877), are

dually echoed in Paul Klee’s Gradation, Red-Green (Vermilion)

(1921) (fig. 12), which preserves the distinctive character of

Egyptian architecture through surreal, but expertly controlled

abstraction, a palace mandala of allegorical structure.

“A mandala-like structure and

a plan representing the world are shown, for example,” states

Brauen, “by the cities of Jerusalem, Rome, Gur, the capital

of the Sassanids, Baghdad, the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate,

and Ecbatana, the first capital of the Indo-European Medes, in

the center of which, on the testimony of Herodotus, stood the

royal palace, behind seven circular walls, each of a different

color.” [14]

Klee’s mandalas, both his kaleidoscopic

middle eastern cities of iconic character and timeless historical

presence in the psyche of mortal thinkers and builders, and his

graphically arresting portraits of interior landscapes made manifest,

curl through the waking and dreaming minds of those who see rather

than simply observe, uncoiling with the sinuous architectural

grace of the human body and the eternal philosophical searching

of the human mind.

Julie Rauer © April 19, 2006

[top]

NOTES:

1. This painting is in the Metropolitan

Museum New York, and can be see at:

http://www.metmuseum.org/Works_of_Art/recent_acquisitions/1999/co_rec_t_century_1999.363.31_l.asp

2. G. Tucci, The Theory and Practice

of the Mandala, translated by A.H. Brodrick, (Samuel

Weiser, Inc. New York, 1969), p.23.

3. M. Brauen, The Mandala: Sacred Circle

in Tibetan Buddhism, (Serindia Publications, London,

1997), p. 11.

4. M. Brauen, The Mandala: Sacred Circle

in Tibetan Buddhism, (Serindia Publications, London,

1997), p. 11.

5. Recently exhibited with more than

sixty other intimate paintings and drawings in the

Neue Galerie’s exquisite exhibition, “Klee

and America”, Neue Galerie, New York NY, from

March 9 through May 22, 2006.

6. M. Brauen, The Mandala: Sacred Circle

in Tibetan Buddhism, (Serindia Publications, London,

1997), p. 11.

7. G. Tucci, The Theory and Practice

of the Mandala, translated by A.H. Brodrick, (Samuel

Weiser, Inc. New York, 1969), p.109.

8. G. Tucci, The Theory and Practice

of the Mandala, translated by A.H. Brodrick, (Samuel

Weiser, Inc. New York, 1969), p.108.

9. Klee died, painfully, at age 61 of

the rare skin hardening disease, Scleroderma

10. J. Helfenstein and E.H. Turner,

Klee and America, (Hatje Cantz Verlag, Germany, 2006),

p. 48.

11. G. Tucci, The Theory and Practice

of the Mandala, translated by A.H. Brodrick, (Samuel

Weiser, Inc. New York, 1969), p.25.

12. M. Brauen, The Mandala: Sacred Circle

in Tibetan Buddhism, (Serindia Publications, London,

1997), p. 31.

13. M. Brauen, The Mandala: Sacred

Circle in Tibetan Buddhism, (Serindia Publications,

London, 1997), p. 31.

14. M. Brauen, The Mandala: Sacred

Circle in Tibetan Buddhism, (Serindia Publications,

London, 1997), p. 31. |

|

asianart.com

| articles

|