asianart.com | articles

Articles by Dr. Pratapaditya Pal

Download the PDF version of this article

March 06, 2018, with an addendum published March 30

Preamble

The article below is reprinted with kind permission of The Mingei International Museum from the catalogue of the exhibition KANTHA: Recycled and Embroidered Textiles of Bengal. Since exhibitions are impermanent and catalogues are not easy to procure without visiting the exhibition in San Diego (CA.), we thought it would be of service to reprint the essay and the notes and comments on the few inscribed kanthas for wider circulation.

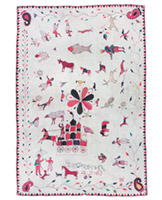

While the exhibition closes in March 2018, fortunately the forty-two examples displayed and fully illustrated beautifully in the catalogue will remain in the permanent collection and be accessible for future viewing and study. Most were given to the museum by Courtenay C. McGowen, who is also the current chair of the museum’s Board of Trustees. Holder of a Master’s Degree in art history from Columbia University, she was for eight years an assemblywoman in the Nevada legislature. Apart from kanthas, she has also collected Bastar bronzes, Naga textiles and adornments from the subcontinent and Chinese snuff bottles. She is the author of the entries on individual kanthas in the catalogue, while John Gillow provides an overview of the subject.

The Kantha collection at the Mingei is not only the largest on the west coast of America, but joins three thousand other items of artifacts and crafts of the widest diversity possible from the Indian subcontinent under one roof. In fact, while the Los Angeles County Museum of Art possesses the largest and most diverse repository west of the Grand Canyon for the history of the pre-modern classical art of the Indic civilization, so does the Mingei in the area of folk, tribal and everyday arts, of which kanthas, reflecting the dreams, skills, and aesthetic sensibility of ordinary women of Bengal, constitute an important contribution.

I am delighted to offer this brief appreciation for three reasons: First, it is a pleasure to collaborate once again with my longtime colleague (and former student) Christine Knoke Hietbrink on an exhibition. Second, I appreciate the fact that the collector of these “embroidered dreams” of countless anonymous women of Bengal was initiated in her avocation by C. L. Bharany of New Delhi, who, as mentioned below, also inspired my own interest in these artifacts. And third, I am happy to celebrate their donation to Mingei International Museum, with which I have been associated for a long time.

Even though I don’t remember, when I first arrived on terra firma eight decades ago in the town of Sylhet (in what is now Bangladesh), I was immediately wrapped in a kantha. In fact, all of the wraps in my family’s home were handmade embroidered cotton quilts—perfect for the mild winters of Bengal. Up until I was sent to a Christian missionary boarding school, I continued to use a kantha as a wrap while I slept. At school, however, coarse, drab, and gray woolen blankets replaced the comfortable, cozy, colorful cotton covers from home.

Even now at home in Los Angeles, we use cotton covers, though they are made in Rajasthan with colorful printed material and without the rich embroidered imagery or vibrant designs of kanthas. Alas, the quilts of Bengal, products of the love and thrift of housewives, have become collectors’ items to be saved, stored carefully, and displayed at museums rather than serving their original functional purpose.

The Bengali word kantha (pronounced “kaanthaa,” with two long a’s and a soft dental t) is derived from the Sanskrit word kanthaa (pronounced “kawnthaa,” with the first a short), which is very old; its exact origin may be from a non-Sanskrit source. It denotes a rag or patched garment, and was originally applied to one worn by an ascetic, yogin (practitioner of yoga), or mendicant, signifying thrift.

Wearing garments made from discarded rags was recommended to monks by the Buddha (sixth–fifth century BCE). Because monks begged for their daily food (and still do in Theravada communities), it was considered appropriate for them to wear only patchwork garments which, according to the Buddha, “should look like the rice fields of Magadha” (now south Bihar, India). I still remember from my childhood women going from door to door in Calcutta (now Kolkata), bartering new pots and pans for old saris.

Apart from thrift and utility, the kantha symbolizes both the emotional experiences and aesthetic aspirations of its maker. Usually made by a homemaker from an economically disadvantaged family, the kantha represents both devotion and labor, often achieved quietly and privately during spare moments snatched from a long day of domestic duties. This labor of love was an outlet for creativity and recreation for the amateur artist who never attended art school. However, there is nothing amateurish about the artwork that was produced, often as a gift for a loved one, just as in the West, knitting socks or a sweater or muffler can be considered an act of love. The kantha communicates this love as it envelopes you during the embrace of sleep, a constant physical reminder of sweet memories that linger for years.

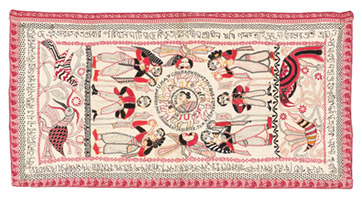

Kanthas can have other meanings, too. A few of the kanthas in Mingei International’s collection contain brief inscriptions in the Bengali language and script. While most of these merely identify the figures depicted, naming deities or the theme and motifs, others give the names of the creators or recipients of the kantha. In one (Plate 25), we are told that the kantha is meant for “Ronida” (an elder brother or cousin named Roni). In a second example (Plate 24), the owner’s name is given as “Satish Chandra Naskar,” likely the head of the family. In a third kantha (Plate 21), the maker includes her name as “Shrimati Umatara,” the honorific prefix srimati being Ms. In yet another example (plate 26) rendered for Shri Chandra Kumar Sen, the word bandhani (or bandhan?) is used as a synonym for kantha. (See below Notes for further information.) The longest and most elaborate inscriptions, in both Bengali and English, occur on a cover from Faridpur in Bangladesh (Plate 38); it has been discussed below but needs further study by scholars more knowledgeable in the history of this art form than I am.

In the preface to this volume, it was gratifying for me to read the collector’s tribute to Chhote Bharany “for opening her eyes to so many aspects of Indian art” and for being the source of several of the examples in this collection. As noted earlier, I, too, echo these sentiments and must admit that, although I have used kanthas from the moment I was born, and later learned about them and their aesthetic merit from the writings of such pioneering collectors as Gurusaday Dutt and Stella Kramrisch, I too have been inspired by the contagious enthusiasm of Bharany, who is passionate about the beauty and charm of these embroidered dreams of mostly unknown Bengali women.

By pure coincidence, as I was penning these words of appreciation, I received an email from a friend in New Delhi that began with a few words about his recent meeting with our mutual friend, the nonagenarian Bharany: “We were with Chhote for dinner yesterday, and saw an exquisite kantha he had procured recently . . . Wonderful that he still manages to come by such pieces and buys them. God bless him.”

Let blessings also rain on Courtenay McGowen for saving and preserving these rare objects and donating them to Mingei International Museum, where they will be united once again from a Bengal that is no more.

Notes and Comments on Inscriptions

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

2. The inscription surrounding the rectangular field of the kantha is in Bengali characters and to my knowledge, is unique. A literal English translation is as follows:

The names and deeds of all the wise and religious persons who were born in this sacred land of India and enhanced its glory in ancient times are forever preserved. Numerous changes have occurred in this land of India, but there has been no diminution of the admiration and respect for these great souls among the masses of the country. The originator of the Buddhist faith was Mahatma (Great Soul) Shakyasimha.

Comments: The inscriptions make this an unusual example of a kantha. The Bengali panegyric clearly indicates devotion to the Buddha, but, the name in the English inscription—Uma Charan Bhattacharya—is that of a Hindu, and a brahman to boot. It should be noted that, in the adjoining district of Chittagong, east of Faridpur, Buddhism has survived until the present, though precariously. A proper explanation of the two inscriptions will require further study, but the use of literary language and historical sensibility of the composer of the inscription are noteworthy. Could the kantha had been made for presentation to a Buddhist temple or monastery in Chittagong?

In any event, if the characterization of the work in the catalogue (see Plate 30 text) as “an oar, a pillow cover,” is correct, then indeed it would be a giant’s pillow; it could of course be a bed cover. However, the central mandala contains the bust of a lady, identified in English as Kali (the name of the owner’s wife?), in western dress. The space between the central medallion and the border of the English inscription is filled with walking elephants, which may symbolically represent the Buddha, as one encounters in the Buddhist moonstones in Ceylon and in early Indian Buddhist iconography. The mandala is flanked by pairs of peacocks with entwined necks. Curiously also, the figural composition below and above the mandala are of two males, dressed in European attire and flanked by a pair of winged-female angels with garlands. All of them wear European costumes but with Bengali features. They vaguely recall 18th century Portuguese figures rather than contemporary British. At the top and bottom, separated by stylized trees are a pair of confronting, imaginary and colorful birds.

Addendum

In a recent review of the Kantha exhibition in a Bengali magazine, the reviewer observed that the late Stella Kramrisch, the eminent Indian art historian, had suggested, (presumably in her 1930s article in The Journal of Indian Society of Oriental Art) that some of the designs in kanthas may have been influenced by Buddhist mandala paintings that were once familiar in Bengal in the Pala-Sena age (11th-13th centuries) [1]. Indeed, such mandalas may have continued to have been produced in the Chittagong region of Bangladesh where Buddhism still has managed to survive. She was of course referring to the large circular lotiform motif that dominates the designs of kanthas. However, this design is encountered on the ceilings of the Buddhist caves at Ajanta and also in the Jain stone votive ayagapatta familiar in the art of Kushan (1st-3rd century CE) Mathura in Uttar Pradesh. They are probably of much earlier origin in India, originally symbolizing that sun or the sundoor as shown by Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. The motif was had a long life in the subcontinent through the medium of textiles in both royal and devotional contexts and may be observed in Mughal and Rajput paintings in canopies above rulers and divinities. In any event, the Buddhist association may explain the long Bengali eulogy of Shakyamuni in one of the larger kanthas in the exhibition (see Plate 38 above).

In the article I have also mentioned that one of the earliest uses of kantha, to cover the monk’s body, is found in early Buddhist literature when the Buddha instructed the monks to be self-sufficient by wearing an apparel made with discarded rags collected as alms, as they did their daily meal, and continued in Buddhist countries.

Fig. 1 |

Fig. 2 |

Fig. 3 |

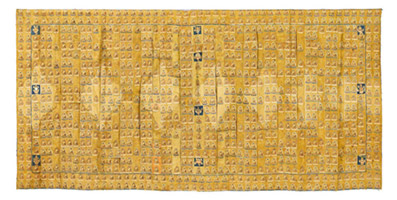

A perfect but stylized example of a chivara of sewn rags may be seen in a gilded Buddha image, purportedly from Tibet on the cover of a recent auction catalogue (fig. 1) [2]. (It is ironic that a robe that was originally intended to signify poverty and self-abnegation was sold for over three million dollars). An example this type of robe – in fine silk rather than rags - was seen in another recent auction (fig. 2). In exhorting the monks to wear such stitched rag garments, the Buddha made an aesthetic statement when he compared them to the rice fields of Magadha (modern Bihar state) as if he was looking down from the Rajgir hill. From the air the fields appear as patchwork consisting of small, uneven plots separated by raised, mud and stone borders (fig. 3). Ironically, again in the gilt bronze the unknown artist has embellished the borders with metal pearl motif.

It was a common practice among wandering mendicants and yogis in the Buddha’s days to go around in such patchwork quilts or covers called a kantha. One of the earliest instance of the occurrence of the word, as pointed out by Monier Williams in his indispensable Sanskrit-English dictionary is in a verse appropriately in the collection titled Vairagyashataka by the 7th (?) century or earlier poet Bhartrihari. The work shataka = 100 while vairagya literally means renunciation. In the “poetical” translation of Barbara Stoler Miller, it goes:

For our purpose however, a more literal translation may give a better sense:Even though my food is alms,

A single meager daily meal;

Though my bed is bare ground,

My servant no one but myself;

Though my clothes are tattered,

Patched with scraps of rags;

The hires of the sense

Never grant release [3].

As far as I know not only is this the earliest occurrence in Sanskrit of the word kantha (pronounced kanthaa; kaanthaa in Bengali) but also the first literal and accurate description of the garment. Could one also claim that these kantha robes for the Buddhist monks represent the earliest examples of the “collage” method” of constructing or creating an artwork?My single tasteless (nirasam) meal is alms I daily beg,

My bed, the earth, my own body, the sole servant,

My garment a kantha made with hundreds of old scraps,

Alas, (ha) alas (ha) I cannot yet eschew my possessions.

It seems from the monks’ attires in all Buddhist communities across the globe that the Buddha’s injunctions regarding sartorial matters was not strictly followed in practice, though in visual iconography we encounter a mode of garment, worn by the Buddha himself and sometimes by monks in paintings, that suggests a patchwork kantha.

March 23, 2018

Endnotes

1. Madan Mukhopadhyay; Kanthar Kathamala [Wordgarland of Kanthas] Weekly Bartaman 30th year, no. 36 (January 20, 2018): 46-47.

2. Indian, Himalayan and Southeast Asian Works of Art, Christie’s New York, 21 March 2018, cover and lot 206.

3. Barbara Stoler Miller, Bhartrihari: Poems. [New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1967]. There is no solid evidence regarding Bhartrihari’s dates. Miller, accepting the Chinese pilgrim I-Ching’s (I-tsing) mention of a grammarian Bhartrihari, gives the mid-7th century as his date. However, it is strange that she did not note that the Harvard Sanskritist and scholar Daniel H. Ingalls had assigned Bhartrihari c. 400 CE date (see An Anthology of Sanskrit Court Poetry [Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1965]: 32.

Dr. Pratapaditya Pal

Dr. Pratapaditya Pal is a world-renowned Asian art scholar. He was born in Bangladesh and grew up in Kolkata. He was educated at the universities of Calcutta and Cambridge (U.K.). In 1967, Dr. Pal moved to the U.S. and took a curatorial position as the 'Keeper of the Indian Collection' at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. He has lived in the United States ever since. In 1970, he joined the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and worked there as the Senior Curator of Indian and Southeast Asian Art until retirement in 1995. He has also been Visiting Curator of Indian, Himalayan and Southeast Asian Art at the Art Institute of Chicago (1995–2003) and Fellow for Research at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena (1995–2005). Dr. Pal was General Editor of Marg from 1993 to 2012. He has written over 70 books on Asian art, whose titles include, Art of the Himalayas: Treasures from Nepal and Tibet (1992), The Peaceful Liberators: Jain Art from India (1994) and The Arts of Kashmir (2008). A regular contributor to Asianart.com among other journals at the age of 85+, Dr. Pal has just published a biography of Coomaraswamy titled: Quest for Coomaraswamy: A Life in the Arts (2020).

Articles by Dr. Pratapaditya Pal

asianart.com | articles