asianart.com

Articles by Amy Heller

HOME | TABLE OF CONTENTS | INTRODUCTION

Download the PDF version of this article

by Amy Heller

Published May 2020

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

This research seeks to explore the terrain of Tibetan art by reflections on Tibetan art in the 21st century, focussing on contemporary works by Tsewang Tashi, Benchung, Gonkar Gyatso, Gade and Sonam Dolma Brauen. To what extent do their works of art reflect a continuum of the fluctuations of Tibetan art over time? May these works of art be viewed as a mirror, to a certain extent, reflecting the multi-cultural international relations - economic, political and geographic - entertained by those living on the so-called Tibetan plateau, criss-crossed by trade routes since time immemorial, expressing the active exchanges by Tibetans with their neighbours in all directions?[1].

As stated by Leigh Miller[2], "it was precisely Tibetan artists’ extraordinary capacity to invite, study, and master techniques from their borders, and re-fashion them within a distinctly Tibetan environment and aesthetic, that has created an art tradition world renowned. Throughout Tibetan history, the cultural spheres of philosophy, religious practice, astrology, medicine, and art have been imported and incorporated with indigenous knowledge to create unique Tibetan systems that perfected these arts and sciences."

One may recall as well as that the very introduction of Buddhism reflects foreign religious cults reaching Tibet thanks to trade routes and cultural interaction with neighbouring cultures, which is also the case of the Bon religion which claims origins west of Himalayas towards Iran. Over the centuries, time and time again, foreign artists and foreign aesthetic models as well as foreign religious practices were introduced to Tibet, from all borders, whether from Central Asia, China or Nepal and India, with ebbs and flows of blendings with Tibetan schools of art and the influential works of individual Tibetan master artists, leading to the extremely heterogenous artistic production by Tibetan artists during the 20th century. Certain artists chose to remain exclusively within the framework of traditional Buddhist and Bonpo religious art, while others were exposed to multiple foreign influences as well as formal artistic education in painting and sculpture.

In this brief article, the paintings, sculptures, photographs, video and performances presented document the diversity of influences and the unique creations and ephemera produced in the context of Tibetan art during the early 21st century. The selection presented here reflects four criteria developed by Tsewang Tashi, an artist himself and professor of the School of Arts, Tibet University, Lhasa, which he deemed useful to determine case selection of contemporary Tibetan artists:

· The artist should be Tibetan and from Tibet (including Tibetans from other Tibetan cultural areas).

· The artist should mainly have lived in the modern Tibetan society.

· The artists should have received different cultural influences.

· The artist’s work should be distinctive and different in terms of his or her approach and concepts with regard to traditional Tibetan art (mainly thangka painting).[3]

During the Bergen 2016 IATS seminar, it was hoped to exhibit works of art by Tibetan artists Gongkar Gyatso and Sonam Dolma Brauen, and include Gongkar Gyatso among the participants of Panel 46 discussing Tibetan art and Tibetan identity. This idea was conceived following the inspirational exhibition in the context of the 2006 IATS in Königswinter, Germany, " Modern Art from the Roof of the World: Contemporary Painters from Tibet " organized by the painter Elke Hessel. Hessel focussed principally on artists of the Gendun Chopel Artists Guild in Lhasa, notably works by two Lhasa artists, Tsewang Tashi and Benpa Chungda. Tsewang Tashi participated in the IATS seminar discussing "Twentieth Century Tibetan Painting".[4]

Benchung

The artist Benchung exhibited paintings in the show and at IATS seminar, a video of his performance entitled Floating River Ice was presented (see Fig. 1). The video was filmed in the dark of deep night, interrupted by flashes of bright headlights of cars. The video shows Benchung in the process of making broad gridlines on the streets of Lhasa in tsampa (editor's note: tsampa is flour made from roast barley, the staple crop of Tibet and the high Himalayas. It is the quintessential Tibetan food). The flour lines resembled white chalk. Inside the largest rectangular outline, Benchung made a silhouette of a standing man; inside one of the squares, he made two smaller circles, as if eyes. The traffic at the intersection during the night displaced the lines and forms. Eventually, during the passing of time, the stark outlines completely dissolved. The performance was filmed in slow frames, the montage of the video in a crossfade technique, alternating a gradual or rapid crossfade. Hessel analysed these gridlines as related to the construction process of the sand mandala of Tibetan Buddhist monks, which require such lines as a basis of performance, and at the conclusion of the ritual cycle, the sand mandala of Buddhist monks will be deconstructed and discarded. Hessel's analysis brings a Buddhist perspective to Benchung's performance.[5] In another video by Benchung, a Buddha sculpted in butter slowly melted on a pane of glass.[6] In his ephemeral video performances, there is a simultaneous reference to the urban reality of modern Lhasa, yet the use of tsampa transcends any specific time period. There is also the recall of Buddhist ritual practices, and a reflection on alternating passage of vehicles and passage of time in darkness to dawn and cold to heat, recalling as well as the Buddhist concept of the transient nature of all phenomena.

Fig. 1: Benchung - Floating River Ice

Tsewang Tashi

Fig. 2

Tsewang Tashi presented hyperrealistic paintings of portraits of young Tibetans. His explanation is very clear, "What I pay attention to is to the real people and environment as my source of inspiration. I believe that if contemporary life around us is ignored, real contemporary art cannot be created. I avoid seeking novelty in my works, because a lot of these things are imaginary or expectations by outsiders who are looking for "Shangri-la" or "Savage Culture". I am living in a real society and have feelings and thoughts as other people in the world. I want to speak as humankind in general."[7] Tsewang Tashi showed additional portraits in his 2009 exhibition, "Untitled Identity" at Rossi and Rossi, London (see Fig. 2). The catalogue texts reflected his aesthetic development from a painter of landscapes to a portraitist with a distinctive vision of his subjects. As Fabio Rossi described his technique, “ basing his paintings on photographs taken in the streets of Lhasa and then digitally manipulated...These over-sized faces can be seen almost like depictions of the human terrain, the use of striking colors reminds one also of the saturated landscape of Tibet.[8] In these works by Tsewang Tashi in the early 21st century, portrait photography fused with portrait painting in a very striking manner.

Fig. 3

Tsewang Tashi's aesthetic sensitivity towards photography and painting may be understood in the context of photorealism or hyperrealism, in the sense of American and British artistic movements of the mid-20th century which emerged from Pop Art, in which painters used photographs, photographic techniques and grid-scale overlay to reproduce on canvas the visual 'reality' of the photograph using the medium of paint. A prime example among the pioneers of the photorealism or hyperrealist movement is the work of Malcolm Morley ca. 1966 (see, for example, Fig. 3. SS Amsterdam in front of Rotterdam, M. Morley, 1966, https://www.christies.com/lotfinder/Lot/malcolm-morley-b-1931-ss-amsterdam-in-5916633-details.aspx.)

As we will discuss below, not only for Tsewang Tashi, photography and integration of photographic influences and techniques are integral aspects of the work of Gonkar Gyatso and Sonam Dolma Brauen. More than the western school of photorealism, there is a uniquely Tibetan model represented in mid-20th century paintings among the monuments of Lhasa. This model is well known to contemporary Tibetan artists.

It was in 1956 that the uncanny mural painting "The Enthronement of the 14th Dalai Lama" was created by Amdo Jampa (1916-2002), then court painter to the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, on a prominent wall in the Norbu Lingka Palace (see Fig. 4). While individualistic portraits in sculpture have been cast since centuries, the painting by Amdo Jampa is a radical departure from this tradition.[9] Amdo Jampa painted replicas of photographic portraits as elements integrated in his two principal mural paintings in the Norbu Lingka Palace in Lhasa, creating a distinctly Tibetan aesthetic model of photorealism in painting long before western photorealism. How to explain the genesis of Amdo Jampa's murals? Amdo Jampa was largely self-taught, having been sensitized to Tibetan thangka paintings during his adolescence in Amdo, in the Labrang monastery. In the shadow of the monastery, Labrang was a multi-cultural town inhabited by sedentary and nomad Tibetans, Hui Muslims, and Chinese, with medical care provided by American Christian missionaries. The latter maintained good relations with the two most important personnages in Labrang, Jamyang Shepa Rinpoche, titular head of Labrang Monastery, and his brother, Aba Alo, the most important military and political figure in Labrang.[10] Eventually Amdo Jampa painted Aba Alo's portrait. It was in Labrang that Amdo Jampa first saw photographs, which fascinated him:

"I saw a photograph on the altar of my landlord’s house. I took it in my hand and found that it was a portrait of the 9th Panchen Lama. It had a convex and concave effect and everything was so clear, for example some gray amongst the dark hair and beard could be clearly seen in the photo, and I wondered how these effects had been created. After I had been thinking for a while, I realised that all these effects were created by the dark and light, so to speak. Black creates shade and concave; white creates light and convex. I tried to make a similar image, but I did not succeed. So I slowly figured out that the proportions and forms also are important factors for making a realistic image. I measured them carefully and finally the image got much better. Then I understood how to apply chiaroscuro and appropriate proportions to capture the characteristics of the model as well as other important factors for achieving a realistic effect. I showed the painting to others and they immediately recognised who it was. Then I painted many lamas and officials."[11]

Fig. 4

Apparently, Amdo Jampa was already consciously imitating reality in his portraits, thus, to a certain degree, eschewing certain norms of Buddhist iconographic canons such as the restrictions and codifications of proportions. As he honed his personal techniques of observation by using photographs for reference, he was simultaneously opening a new range of visual possabilities for his art. Amdo Jampa moved to Lhasa where photography was less of a novelty due to pilgrims and merchants traveling to India and Nepal, while as residents in Lhasa, H. E. Richardson and the British consular personnel were top-notch photographers - along with their cameras came film development and enlargement devices.[12] In this Lhasa milieu keen on photography, with the secular elite of Lhasa society showing a certain degree of permeability or even enthusiasm for modern western influences during the 1940's and 1950's, Amdo Jampa's notoriety as a painter developed further. Appointed court painter to the 14th Dalai Lama shortly after his enthronement in 1950, he was engaged to make two murals in the Norbu Lingka palace, in 1956 : "The Buddha Teaching at the Deer Park in Sarnath" and "The Enthronement of the 14th Dalai Lama. In both there are realistic elements, but in the latter painting it is far more pronounced: here Amdo Jampa inserted painted imagery identical to photographs of the faces and clothes of the individuals involved in the enthronement. The painting follows a traditional Tibetan composition based on a lineage "tree of assembly", represented as a triangular "tree" structure in which the highest ranking religious hierarch is at the apex of the "tree". At the time, it was revolutionary in Tibetan art and in Buddhist art for the Dalai Lama to be depicted in painting in a realistic human aspect.[13] In the words of Tsewang Tashi, "This was a remarkable event in Tibetan art history because the location of the two murals (editor's note: in the summer palace of the Dalai Lama) signified the acceptance by the élite both of painting in a new style and of such work being displayed in an important place."[14]

Amdo Jampa's work in this mode of "realism" continued off and on for many years, through at least to ca. 1980.[15] It is beyond the scope of the present research to focus on this interim period, which would certainly be worthwhile to investigate further. However, bearing in mind Amdo Jampa's murals and portrait paintings, we can examine the 21st century works with all the more attention to the influences of photography and photographic techniques.

In Bergen, despite the convenors' support and strong encouragement to hold an exhibition of works by the artists Gonkar Gyatso and Sonam Dolma Brauen, due to construction in the campus, the plan had to be dropped. In lieu of the exhibition, my presentation focussed on these two contemporary artists as well as the Lhasa artist Gade and a selection of their works to address the panel theme of Tibetan Art and Tibetan identity. My hope was to examine and consider what contours help to understand the parameters of Tibetan art in this selection of Tibetan artists, both inside and outside Tibet. One element which has a resonance for both Gonkar Gyatso and Sonam Dolma Brauen is their appropriation of photographic techniques as well as photographs, although both artists also refer in their work to non-photographic media; Gade also has included photographic references in some of his work.

Gonkar Gyatso

Gonkar Gyatso's photographic installation My Identity No. 1 - No. 4 is certainly one of the best known works by a Tibetan contemporary artist. For the Bergen IATS seminar, Gonkar Gyatso wrote about the genesis and development of this installation:

"My Identity was born out of my desire to explore the ways in which artist is a product of the culture and politics in which he or she is living. I left Tibet for India in spring 1992 with a heavy heart and overwhelmed by a longing to find and know a more authentic Tibetan identity. I thought that perhaps Dharamsala was as, Tibetan author, Jamyang Norbu recently said, the Yan’ an (editors note: Yan an is the town where Mao terminated the "Long March" of 1934-35) of exile Tibetans. I spent a lot of time at the Tibetan Library and Archive in Dharamsala and it was there I came across a book with the iconic image by C. Suydam Cutting of a Thangka painter on the cover. Even though Yan’ an was long gone, the image seemed to capture something quintessential about being a painter and being Tibetan and I tucked it away for future use. In London summer of 2003 I released the first four in a series of photographs called My Identity- referencing that photograph; I created an installation representing a painter in his studio in four different political environments. Over the years many people have asked “what will be the fifth My Identity”? After nearly a decade of travelling between the West and China and Tibet, it finally occurred to me that I wanted the fifth image to be taken in Lhasa. It took months to source the materials for the installation and find the right location. Finally, with the help of many friends, we shot the 5th photograph in my sister’s house in Lhasa October 2013 and finished editing in NYC this year (2015)."[16]

Fig. 5

Gyatso's discussion shows the importance of this historic photograph of the Lhasa painter and how he departed from the original in four successive contemporary political and social commentaries which he presented as a photographic installation. See the original four tableaux, Gonkar Gyatso, My Identity: No. 1 - No. 4, Photographs, Installation. 61,5 x 78 x 3,4 cm, (London, 2003).[17] The original photograph by Cutting was studied by Valrae Reynolds, former curator of The Newark Museum where it is conserved. The painter has been identified as the court painter of the 13th Dalai Lama, sitting in Norbu Linka.[18] Strikingly, in the fifth element of the series, in fact Gyatso reiterated Lhasa as the location but switched the time frame to 2015 (Fig. 5). There is a sense of humour as well as a bit of political commentary in the subtle elements of the decor of each photographic installation, such as the inclusion of the portrait of Aung San su kyi as the subject of the portrait the artist paints - painting a living person rather than a Buddhist deity in his tableau My Identity: No. 5.[19]

Fig. 6

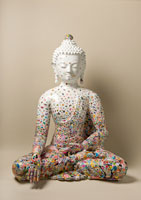

Perhaps less well known is how Gyatso has exploited the medium of photography in his creation of sculpture. Gyatso's sculpture Untamed Encounter is constituted by a series of life-size statues of Shakyamuni, based on a three-dimensional laser scan of a 30 cm fourteenth-century Nepalese sculpture, which he transferred to a three-dimensional printer to make a mould in which the sculpture was cast in resin, then enhanced by pigment and stickers, height of 100 cm. (Fig. 6). This innovative work transcends the scale and the geographic origins of the original model, simultaneously introducing subtle humour to the noble moment of the Buddha's Enlightenment.[20]

Gyatso explained the evolution of his long work on the Buddha,

"This is perhaps the work that I am now most well known for. In 1986 I made my first “Buddha” work and completed the last one earlier this year (2015) for a museum show in Massachusetts. Over the last 20 years the Buddha work has evolved and shifted. In the late '80's in Tibet the Buddha I was working with was decapitated and filled with anger. I spent the early 90's in Dharamsala; there Buddha figure was infused with more of a spiritual awareness that I thought I was developing. I studied Thangka painting and followed the traditional iconometry of painting the Buddha. However, I also noticed that the figure of the Buddha was accessible to a wide number of people. When I began working with the Buddha in London in the late 90's and into the 21st century, the notion of accessibility became even more important. The work became more playful and infused with humor and reflected a more global awareness. In the past five years, as I've traveled between New York and China, the form has become more of a vehicle to express a myriad of ideas which allows me to reflect and react to news, events and trends around the world. The more I work with the Buddha the more secular it has come."[21]

Gade

Fig. 7

Gade is a Lhasa artist, member of the Gendun Chopel Artists Guild. Among the panelists of the IATS Bergen conference, Leigh Miller (see: The Look of Art without Religion: A Case Study in Contemporary Tibetan Art in Lhasa) has discussed his works in detail over many years. My presentation thus focussed on a very specific period, and specific techniques then used by Gade at the time. During the period of the construction of the Beijing - Lhasa railroad line, in Lhasa many new urban zones were in construction as well as major arteries for the city of Lhasa. In this context, Gade conceived the Ice Buddha, in which he modeled a Buddha in ice, placed it in the Kyichu River, at specific locations. It is thanks to Gade's personal authorization that here are reproduced the testimonies of his collaboration with the photographer Jason Sangster during which time the following photographs were made. Gade's Ice Buddha is a small Buddha seated on lotus pedestal sculpted in ice made from the waters of the Kyi chu, which was subsequently replaced in the original waters of the Kyichu where it melted and dissolved, into a formless realm. The work Ice Buddha subsists as a series of photographs and video by Gade and J. Sangster.

Fig. 8Conceptually confronted with the photograph of Gade's Ice Buddha, the viewer finds a work which obliges the recall of the experience of the impermanence of all phenomena, insofar as the Buddha modeled in ice will inevitably melt. The representation of the Ice Buddha was revered by placing it carefully in the waters of the Kyichu river, in relation to different specific locations, to be photographed for posterity. The results are here (Fig. 7, Gade and J. Sangster, Ice Buddha I, 2006, and Fig. 8, Gade and J. Sangster, Ice Buddha I – Liu Bridge). The first exhibition of these photographs was in 2006, in Lhasa.[22] Thorough analysis of the work of Gade during many years by Leigh Miller does mention these sculptures, but almost as an afterthought, in passing, far away from Gade's genuine artistic production and far away, conceptually from his concentration on imagery imported from western iconographic sources, such as comic strips, which he aesthetically studies in detail and then transforms to suit a Tibetan paradigm of his configuration. In this sense, Gade is expressing Tibetan identity as a metamorphosis of an image of foreign origin, which he appropriates and controls to encourage the viewer in her/his way of perceiving Tibet. The individual images Gade has produced are striking, aesthetically and temporally. The Ice Buddha, no. 1, is also a stark statement on the present evolution and dissolution of a modern Buddha sculpture within the geographic zone of Lhasa, itself in total modernizing metamorphosis. The Buddhist concepts of impermanence and transience of all phenomena is clearly implied, while in a 2016 interview about the subsequent Ice Buddha Gade placed near Mt Kailash, he evoked reincarnation as well:

Tsesung Lhamo: In 2006, you placed a statue of Buddha made from ice into Lhasa river and used photos to document how it slowly melted away. More recently, you reconstructed the ice statue at the foot of Mt. Kailash, at the lakeside of Mapam Yutso. Where did you get the inspiration for this ice Buddha? And why did you reconstruct it in Ngari?

Gade: I have talked about this ice Buddha too much, people even call me the “ice Buddha artist” (laughs). So in art you really cannot surpass yourself. If you happen to produce something very good and want to then produce something even better it is almost impossible. Always having to live in one’s own shadow can be really painful. The idea behind this ice Buddha was to express the Buddhist notion of reincarnation. From nothing to something and then back to nothing; water turns into ice and ice slowly turns back into water; this is a kind of reincarnation. In the process of melting, the shape is constantly changing, it is a status of impermanence. But of course, there are many other interpretations of this piece. The artist is merely the creator, but the interpretation is left to the audience. The artist does not have the sole authority over the interpretation of his work.

Tsesung Lhamo: I thought the piece represented global warming.

Gade : Yes, it can be interpreted as being about environmental protection, this is the nature of art works. Different people see different things: There are a thousand hamlets in a thousand people’s eyes. And the ice Buddha is really open to interpretation. As to why I reconstructed it, well, originally I should have used video recording to capture the melting process, but didn’t have the technology at the time. Plus, I suffer from extreme procrastination, never got round to doing it again. Ten years just passed in an instant. It’s frightening when you think about it. Another reason is that I have always wanted to place an ice Buddha at every important river and holy lake in Tibet. So I decided to place one at the lakeside of Lake Mapam Yutso[23].

In the same interview Gade discussed Tibetan art and Tibetan cultural identity, and in the context of the present inquiry, his remarks are pertinent:

For instance Tibet, what is Tibet? Everyone has different ideas and different experiences and it is precisely these different elements that make up Tibet; it is not simply “the white clouds in the blue sky,” “the snow mountain and the grasslands” or the “beautiful Buddhist temples”. People from our generation are highly detached from our culture and mother tongue. After having been cut off from our spoken and written language as well as from our culture and history, can we really say that we represent Tibet? Early on, I would also paint a mystified Tibet, would contribute to the “Shangri-La-isation” of Tibet, would essentialise Tibet, but then I gradually came to think that this was fake. “Othering” Tibet is bad, but even worse is when Tibetans themselves “other” Tibet. Our own pieces of art are completely unrelated to your and my lives. This is why contemporary art has given me a voice; it is a tool that I can use to get as close to the truth as possible.

–But there are still traditional elements in the techniques adopted by contemporary artists, right?

–Yes, in my case this has always been true. I have always tried to bring traditional Tibetan art into a contemporary art context; I am still deeply fascinated by traditional Tibetan art. The attention to detail used in the techniques and the ability to create narratives is still very enchanting. These elements are not so important in western or Chinese art and I really want to continue this complex art of storytelling because it helps to express my intentions. It originated from an ancient language system, the so-called “native language system” of Tibetan art, which still exudes great vitality, only that it was broken off and has never been fully revived. The art history of any culture tells us that the evolution of art always begins and develops from one’s very own cultural root. This is why contemporary Tibetan art must by no means become a recreation of western contemporary art. It has its very own language and value system.[24]

Sonam Dolma Brauen

Fig. 9

Sonam Dolma Brauen's paintings, video and installations also help to reflect on aspects of Tibetan identity expressed through art. Sonam Dolma Brauen is an artist now living in Switzerland, where she made her home after leaving Tibet as a child and leaving India (Mussoorie) during late adolescence, alone with her mother after the deaths of her father and her sister. Sonam Dolma Brauen also lived in New York from 2008 to 2012. She was recipient of the World Citizen Artists award in 2018 for her work Boomerang (2010), a sprawling floor installation which is sculpted by assembling over 2000 individual ammunition shells to form the shape of a giant boomerang 300 x 280 cm. (Fig. 9 and Fig. 10).

Fig. 10

The World Citizen Artists cite Sonam Dolma Brauen, “Through art, I can express my thoughts about war, about unfairness, and about environment and destruction. This award helps me and supports me to go further with sharing the message of peace and not just give up.”[25] Sonam Brauen further explained in personal interview “I feel devastated because of the extensive use of weapons, but what to do, how can a small woman feeling the devastation by arms - feeling for the defenceless - do something? The idea grew slowly to form a boomerang with many amunition shells – I feel the meaning of it is self-evident.” (see Appendix III, interview of Sonam Dolma Brauen). In this installation, Sonam Brauen is conceptually and aesthetically far from traditional Tibetan art, instead the contemporary political connotations of this work are explicit and pacifist. Simultaneously, her explanation of the work as stemming from her desire to help those who suffer is akin to the central concept of the Buddha's teachings, concentrated on suffering and above all, the alleviation of the suffering inherent to the impermanence of life and the unfulfilled desires of humanity and all sentient beings. The very notion of the Boomerang as a weapon which soars in the air and returns to the original position, seems akin to the Buddhist idea of Karma, of retribution.

In her comments for the World Citizen Artists website, Sonam Brauen explains:

Boomerang is a large, floor-sized installation created from ammunition shells. The shells, which seem to go on forever, provide the imagery that global military expenses amount to vast sums of money spent on war (more than $1.6 trillion as of 2016). It is no secret that the arms industry very often sells to countries and groups that are at war, and war affects all who are involved. Through Boomerang, I am depicting my belief that what we sow, we shall reap, and that as a general rule the boomerang of armament comes full circle.

She further describes Boomerang in relation to contemporary social concepts, not specifically Buddhist or Tibetan:

"Each of the 2,010 ammunition shells in Boomerang is an example of how separate, little things combine to make a whole. If we each do something small to make a difference, those differences will add up and create an expanding wave of change that can create positive outcomes for humanity. "

The situation as described by Sonam Brauen does not relate specifically to Tibet, but rather to a global ecology committment, not specific to a country but stateless ( with no specific boundaries ) and also without a specific political party .

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

In contrast, Sonam Brauen's painting series Yi shen and the installation and performances Gone with the Wind have very specific roots in China and Tibet. Yi shen is Sonam Brauen's title for a series of paintings, abstract with shades of deep grey colors and a brilliant slash of color -- orange, red, as if a recent, bleeding wound in the center of the dark canvas, (fig. 11) or or as if these bright colors are the flames arising from immaterial bodies of light which traverse the darkness (fig 12).

According to Buddhist historian James A Benn, self immolation is a Chinese Buddhist practice which is known since the Tang dynasty. The Chinese term Yi shen "leaving one's body"or "abandoning the body" is one of the three recognized Chinese Buddhist terms related to this practice, while even earlier, in India, there is the tale of the previous life of the Buddha in which a starving tigress is about to eat her cub, and the Buddha, aware of her suffering, dies nearby. By abandoning his body, the Buddha thus provides her with flesh to sustain her life and that of her children.[26]

Sonam Dolma Brauen first started the Yi shen paintings in 2012. From 2009 until 2017, there were close to 200 deaths due to self immolations among Tibetans, especially in rural areas of Eastern Tibet. In 2012, there were 80 people who self-immolated. This situation was a source of major public attention in Tibet, as the individual died a most dramatic death but also the family members were indicted with crimes of incitement or non-denunciation, a tragic situation for all involved. The self-immolations also received media and public attention outside Tibet.

Fig. 13

As a Tibetan living outside Tibet, Sonam Brauen was particularly sensitive to the self-immolations in Tibet. For Tibetans in Tibet, thinking of non-violence and Buddhism, and for those outside Tibet, thinking of the social and religious repression which triggered such vital reactions, the issue of such immolations is very sensitive, very difficult to apprehend. Sonam Dolma Brauen’s installation Gone with the Wind (Fig. 13) and the video of the performance of 2015 (Fig. 14) are a reply, of sorts, to some of the many questions. These two aspects of the installation and the video allow the viewer to reflect on the image of the flames, of the imagination of the fires of the self-immolations, while the installation with the pile of ashes, the butter lamp offer a visual reminder that flames in the Buddhist tradition are also part of Buddhist funerary practices, in the flames of cremation. This fits with the Buddhist concept of life as continuum of transient moments from birth to old age and death, which may be punctuated by cremation, and will eventually be followed by rebirth. In Sonam Brauen's video, by her Tibetan ethnicity and her wearing of specifically Tibetan garments, as she faces the rising flames, it is inevitably a social commentary recalling the self immolations and the suffering of these individuals in Tibet - which prompted their gesture of suicide. Perhaps it is the unknown which is the trigger or fire of the imagination of those outside Tibet, looking inside, and unable to obtain accurate, realistic information - except to see the charred remains of those who self-immolate. Sonam Brauen's fire performance is a transformation of the self immolation. The fire is lit and it is twilight. Sonam Brauen stands staring at the fire, in Tibetan robes and apron. Darkness falls abruptly and she stands and feeds the fire progressively with Buddhist prayer flags, then the white silk kata, the white prayer scarves of homage and still more large-scale prayer flags. The fire takes a vertical stance as if a person were inside the flames. Sonam stands still feeding and feeding the fire, and pauses, holding a long white kata in front of her as she watches the flames rise. Then she dances a circle around the fire several times holding the kata near her heart while the edges of the kata drape along the ground, more or less close to the flames, she is contemplating. Suddenly her circle dance is finished, the litany is broken, the last kata will not be abandonned in the flames. She runs and instead places the kata around the neck of one of the spectators, as if finding a concrete anchor instead of abandonning all to the flames.

Fig. 14: Sonam Dolma Brauen, performance in relation with the installation Gone with the Wind,

video, Art OMI , Ghent N.Y., 2015.

In personal interview Sonam Brauen commented:

"Yes, the self immolations in Tibet, this was tragic for me, that the Tibetans in Tibet were suffering because of the repressive politics, so much suffering that it gave me sleepless nights.

In terms of art, this overwhelming emotion came out gradually, first in abstract paintings (Yishen) and eventually in an installation Gone With the Wind. The Chinese have a concept, the term "Yishen" which means to abandon the body, and such immolation was historically documented in China but before the 21st century, Tibetans had no such concept - it was not known before and due to their acute situation of suffering from the Chinese , the sudden practices of self immolation ensued -- as an expression of suffering."

In sum, Sonam Brauen is giving a very Buddhist attitude to the self-immolations. Rather than reacting to the social phenomena as insurgence or defiance, she sees the self immolations as an expression of the suffering of the people. Although she cannot re-create the precise moments of the self-immolations, the visual testimony she has created with the installation and fire performance allow apprehension of the tension and the emotions perceived. In her video and the installations, the sense of Tibetan identity is amply documented by the Buddhist ritual scarfs, the butter lamps, and the pile of ashes, as if a cremation. As a social commentary, it is both far away from the norm of Buddhist ritual and aesthetically creates a very moving atmosphere.

Fig. 15

In her sculpture installation The Fullness-Hunger Play of My Childhood by assembling giant bones, as if disparate vertebrae, Sonam Brauen is recalling a common Tibetan childhood game, played with yak or sheep bones, where the concave side of the bone refers to "hunger" and the convex side of the bone refers to "satiety". In the children's game, the bones are rolled as if a bit like dice. In personal interview, Sonam Brauen explained that she made scans with a three-dimensional camera focussed on real bones, which were then enlarged to 70 cm each and executed in quartz. She described this work as a commentary on her own life, where at times she experienced great hunger, and also as a social commentary, thinking of so many people in our world who remain hungry, even dying for lack of food, while others are all the time having too much and wasting the food they have. This work shows her utilisation of photographic techniques in the creation and production of the installation.

In Sonam Dolma Brauen's works discussed here, there are frequent visual reminders of her life in Tibet, and Tibetan Buddhist practices, simultaneously as metamorphosis of the context which transforms the imagery from pure memory to aesthetic expression. Tibetan identity - both secular and religious - is thus frequently present to a degree, as well as the sense of belonging to a global identification of contemporary social and aesthetic issues.

In Guise of a Conclusion

The most pertinent questions, in the opinion of the present writer, are: "What is the Tibetanness of this? What makes this art Tibetan" quoting the opening remarks by Tsering Shakya, the renowned Tibetan scholar specialized in Tibetan literature and contemporary Tibetan history, at the 2006 symposium and exhibition "Waves on the Turquoise Lake"[27]. There seem to be no clear and simple answers to these two cogent questions.

Reviewing the art examined here, Benchung used tsampa flour to draw on the pavement of the Lhasa intersection. He has a big white bag of tsampa - as he completes each line, he returns to the bag and pours tsampa from the bag into a dustpan, then empties the white flour on the dark pavement, seemingly oblivious to oncoming cars. Tibetans who see this video immediately recognize the big bag of local Tibetan tsampa flour. Benchung's use of tsampa flour as a medium for his drawing is totally innovative and yet recalls traditional Tibetan civilisation as barley has been the Tibetan food staple since pre-historic times.

Tsewang Tashi's paints portraits of the epitome of beauty of Tibetan youthful faces and bodies. If conceptually similar to the gods and goddesses of Buddhist art who are forever young, Tsewang Tashi has idealized Tibetan ethnicity by his dynamic large scale, intensity of hue and perfection of line.

Gonkar Gyatso creates his tableaux "My Identity 1- 5" with a Tibetan person at center-stage, changing costume every time, surrounded by a kaleidescope of diverse elements - furnishings of each period and on the walls portraits recalling Tibetan, Chinese or international political figures. His work reflects both divine and secular, historical and modern times, often humourous.

Gade's Ice Buddha sculpture is perhaps the aesthetically the closest to traditional Buddhist art amongst all works examined here, due to the handsome and pure form of the Buddha molded in ice. But the photographic work emphasizes both the Buddha and the geographic context in which Gade has chosen to situate the sculpture spanning modern Lhasa architecture to the timeless topography of the sacred lake beside Kailash mountain. Gade has created a social reality which is a metamorphosis of his Ice Buddha sculpture.

Sonam Dolma Brauen's broad aesthetic sensitivity shows in the installations recalling her personal beliefs grounded in Buddhist ideals as well as reflections of the secular games of her childhood in Tibet, haunting memories and thoughts transformed into aesthetic expressions.

Thus the works of the five contemporary Tibetan artists presented here are heterogenous, highly individualistic, multiplying aesthetic or conceptual references to traditional Tibetan secular society, or to concepts of Buddhism, or to Tibetan ethnicity. These artists provide us with an opportunity to pursue the reflections on what may be understood today as Tibetan art in contemporary social and aesthetic contexts, and the complexity of the elusive definition of Tibetan identity.

Footnotes

1. See Appendix I for an historical example of multiple aesthetic and technical interactions by Tibetans and their neighbours in the 11th century which resulted in the Prajnaparamita Manuscripts of Tholing, where the technical prowess of Tibetans to produce smooth large leaves of beige paper allowed an artistic freedom to the Kashmiri and Tibetan painters and the Tibetan calligraphers experimenting with applications thick gold leaf thanks to the abundant gold of Tholing.

2. Leigh Miller, “Meeting Old Buddhas in New Clothes” 2007:5.

3. Tsewang Tashi, Modernism in Tibetan Art, The Creative Journey of Four Artists, PhD. dissertation, Technical University of Trondheim NTNU, Norway, 2014: 135. I thank Tsewang Tashi for kindly sending me a copy of his thesis.

4. Tsewang Tashi, "Twentieth Century Tibetan Painting" R. Barnett and R. Schwartz, Tibetan Modernities, Notes from the Field on Cultural and Social Change, Brill Publications, 2008: 251 -266.

5. https://www.namtso.de/en/tibet-infos/kultur.html for Hessel's remarks. Benchung, Floating River Ice uploaded by Rossi Rossi, 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nlbZzU1HWgU

6. I thank Leigh Miller for this information. Personal communication of March 2, 2014.

7. Tsewang Tashi, 2003, quotation from Peaceful Wind on Tsewang Tashi - https://www.asianart.com/pwcontemporary/gallery2/1.html.

8. Fabio Rossi, introduction, Untitled Identity, Rossi and Rossi, London, 2009.

9. Compare, for example, the numerous iconic portraits of the Fifth Dalai Lama made during his lifetime or just after his death, M. Brauen, The Dalai Lamas, A Visual History, 2005: 84-87, figs. 52-60.

10. Many of the American missionaries' photographs are now conserved in the archives of The Newark Museum, see Valrae Reynolds and Amy Heller, Catalogue of The Newark Museum Tibetan collection, vol. 1. 1983: 60.

11. Tsewang Tashi, op cit, 2014: 156-157, Interview with Amdo Jampa. This quotation by Amdo Jampa does not mention Gendun Chopel as inciting him to paint influenced by photography, which had been the explanation by Jeff Watt, writing in October 2015 and June 2017, see: https://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=4202 has).

12. See Richardson collection, Pitt Rivers Museum photo archive https://tibet.prm.ox.ac.uk/thumbnails_collection_Hugh+Richardson.html

13. The notion of photography of the Dalai Lama was already accepted since ca. 1910, during the 13th Dalai Lama's travels in India, where he was photographed and photo collages were made in Darjeeling studios. However the replica in painting of a photographic representation is yet another parameter.

14. Tsewang Tashi, op.cit. 2008: 254-255.

15. See "the Great Patriotic 11th Panchen, the Panchen Erdeni Choekyi Gyalten", illustrated in Tsewang Tashi, op.cit 2008: Fig 18, and a portrait of the 14th Dalai Lama, 1980, M.Brauen, op.cit. 2005: Fig. 128.

16. Gonkar Gyatso, abstract for IATS Bergen, 2015 (unpublished, quoted with kind permission of the author).

17. These four tableaux have often been illustrated, notably in the 2006 exhibition, Waves on the Turquoise Lake and more recently subject of detailed discussion by Clare Harris, The Museum on the Roof of the World, Chicago, 2012: 248-253, plates 15-18. See also https://www.museumofcontemporarytibetanart.com/GonkarGyatso.html.

18. V. Reynolds, Tibet A Lost World, New York, 1978.

19. See Gonkar Gyatso, My Identity No. 5, exhibited at Rouge Space, New York, New York: http://gonkargyatso.com/exhibition/2015.

20. Previously published as plate 108, described by Elke Hessel in S. von der Schulenberg, E. Hessel, K. Schmidt, M. Wagner, eds. Buddha 108 Encounters, Museum for Applied Arts Frankfurt (museumangewandtekunst), Wienand verlag, Cologne, 2015.

21. G. Gyatso, op.cit., 2015.

22. The making of and first exhibition of Gade's Ice Buddha No. I, with photography by Jason Sangster, was initially described in the blogspot "Leighsangster.com" authored by Leigh Miller, see Appendix II.

23. Quotations from the interview published by Sweet Tea House," A Broken Flower Blossoming in the Cracks: Tibetan Artist Gade Talks About Contemporary Tibetan Art", interviewee: Gade; interview by Tsesung Lhamo, published July 29, 2016, High Peaks Pure Earth (https://highpeakspureearth.com/2016/a-broken-flower-blossoming-in-the-cracks-tibetan-artist-gade-talks-about-contemporary-tibetan-art).

24. Sweet Tea House/ Gade, ibid.

25. https://www.worldcitizenartists.org/compete-for-peace-not-war-2018.

26. James A. Benn, Burning for the Buddha, Self immolation in Chinese BuddhismUniversity of Hawaii Press, 2007: introduction.

27. C. McGranahan and L. Gyatso, "Seeing into Being: The Waves on the Turquoise Lake Artists and Scholars’ Symposium", 2007: 45.

28. P. Harrison, "Notes on some West Tibetan manuscript folios in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art," Pramāṇakīrtiḥ, Papers Dedicated to Ernst Steinkellner on the Occasion of his 70th Birthday. Part I. editors: B. Kellner, H. Krasser, H. Lasix, M. Much, and H. Tauscher, Wien, Wiener Studien zur Tibetologie und Buddhismuskunde 70.1, 2007: 229 -245.

29. See discussion by conservation scientist Dr. Charlotte Eng on the use of gold leaf in the 11th century Tholing manuscripts, and discussion by the present writer on the historical documentation of local gold near Tholing: A. Heller and C. Eng, "Three Ancient manuscripts from Tholing in the Tucci collection, ISIAO, Roma, Part, II. Ms. 1329 O." Interaction in the Himalayas and Central Asia: Processes of Transfer, Translation and Transformation in Art, Archaeology, Religion and Polity. editors: E. Allinger, F. Grenet, C. Jahoda, M.-K. Lang, A. Vergati. Vienna, Austrian Academy of Sciences. 2017.

Appendix I.

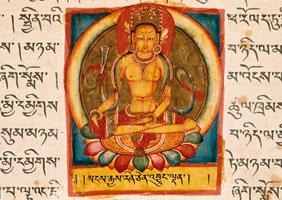

Fig. 16

As an example of the paradigm of multiple aesthetic and technical interactions and cross-cultural references, ca. 1000 - 1100 AD, Kashmiri artists were invited to embellish the newly founded Buddhist sanctuaries in Tholing, then the capital of the kingdom of Guge which formerly spanned Western Tibet and the Western Himalayas. In this effort, the Kashmiri artists sometimes collaborated with Tibetan artists and Tibetan scribes. Their productions evolved to a form of Tibetan art specific to the region, notably the highly refined manuscript leaves of Prajnaparamita sutra produced at Tholing. As may be observed in the representation of the Buddha Ratnasambhava illustrated on a leaf of Perfection of Wisdom sutra, early 11th century, the aesthetic of the imagery - the body proportions, jewelry, costumes - shows the impact of Kashmiri artists invited to Tholing, which became the epicenter of a Buddhist revival, ca. 1000 CE.

These artists were accomplished masters of ancient Indian techniques of contour and shading as well as finishing details with the one haired brush to be used for the finest lines. The presence of small references to color written in Indic script confirms that indeed Kashmiri artists were responsible for the illuminations of these manuscripts while Tibetan scribes were responsible for the fine calligraphy of the manuscripts.[28] The Buddha Ratnasambhava is literally glittering in gold. Not only is he the Buddha of the Jewel (ratna) family, but his yellow body is portrayed inside a painted gold leaf background, his crown is gold leaf as well. This opulent application of gold leaf represents an innovation of the period due to the abundance of gold and great wealth of the Guge kingdom. In this milieu, the artists could take advantage of the excellent quality of Tibetan paper which, contrary to palm leaf, was eminently suited to the thick application of gold leaf, allowing complete background in gold to an extent hitherto unknown in manuscript illuminations.[29] Thus, this illumination of Buddha Ratnasambhava may be understood as an example of the crux of the complexity in defining what is Tibetan artistic production, ca. 1000 CE : a foreign aesthetic model, adapted by foreign artists working with Tibetan artists and scribes, eventually capable of developing a new technique in illlumination thanks to the excellent craftsmanship of Tibetan paper fabrication.

Appendix II.

Source: leighsangster.blogspot.com (author: Leigh Miller).

Inside Out Exhibition May 20-22, Lhasa (2007)

(excerpt about Gade, Ice Buddha No. 1 - Kyi chu river, 2006, Ice Buddha No. 1 - Liu Bridge, 2006).

In a smaller room in the gallery, we installed a series of photographs that document a day’s outdoor temporary installation, Ice Buddha No.1 – Kyi Chu River. Gade conceptualized the event, collaborated with Jason Sangster for the photography, and enlisted the aide of a handful of other artists for the outing (a combined installation and picnic) last December. Gade worked with a sculptor friend to create a special type of mold, and invested in a waist high freezer everyone in Lhasa associates with ice cream sold in tiny shops along the streets. He gathered water from the Kyi Chu, the River of Happiness which runs along the south side of Lhasa, poured it in the mold, and after many weeks of experimentation, had produced lovely clear ice sculptures of Shakyamuni Buddha. We positioned one in the water with the Potala in the background; Gade felt without the Potala this installation could have been any place in the world, but he wanted viewers to see the location as definitively in Lhasa. Then we all observed and documented the ice Buddha melting in the bright Tibetan sunshine.

Gade explained that for him, this project was about the cycle of birth, life and death, coming from elements into form and returning to the elements. As the water from the river froze and then melted again into the stream, so is our cycle of our lives. However, Gade is also particularly interested in what thoughts, emotions, meanings or narratives will come to mind for others, and wishes this work to remain open to anyone’s interpretation. My own associations while observing the process - with decline of culture, violence done to statues and religion in the past (statues raided and destroyed in Lhasa’s temples having been dumped into the same river during the Cultural Revolution, I am told), and the loss of religious knowledge in the land of the Potala – have been shifting lately. When we installed a series of eight 30 x 20 cm photographs in the Gedun Choephel Gallery for the exhibition, I was surprised when Gade told audiences that the chronological ordering of photos could be read either from left to right (melting), or right to left (emerging from the water)! A friend of mine shared her feeling that the gleaming brilliant image conveyed the clarity and luminescence of the Buddha, and could be useful in attracting the attention and arousing the faith of those grown too accustomed to the traditional brilliance of gold and brocade, that is, a new medium for an old purpose. This effect was especially conveyed perhaps by two large prints, Ice Buddha No. 1, 2006 – Liu Bridge (approx. 60 x 80 cm) captured the glowing white ice Buddha from the side, facing the new bridge under construction to connect Lhasa’s western suburbs with the railroad station, arches and bars of steel tower into the sky and reflections in the water ripple around the still point of the Buddha. Looking at this work, I still hear the sounds of the hammers, workmen’s shouts and rhythmic clanking of trucks passing back and forth on unsecured plates of metal. The gorgeous print Ice Buddha No. 1, 2006 (approx 80 x 60 cm) is a close up of the radiant ice Buddha surrounded only by deep blue waters, reflection caught in the ripples stirred by a gust of wind.

Appendix III.

Conversation between Sonam Dolma Brauen and Amy Heller (2017, revised 2019)

SDB : at present, I am making an interruption of work - taking a pause can be part of the creative process.

AH : In my presentation at the IATS Bergen seminar, you kindly let me show the video of your performance in relation with the installation Gone with the Wind, Art Omi, Gent, NY, July 2015. Can you explain a bit the content and the context, please. Is it related to the self immolations in Tibet ?

SDB : Yes, the self immolations in Tibet, this was tragic for me, that the Tibetans in Tibet were suffering because of the repressive politics, so much suffering that it gave me sleepless nights.

In terms of art, this overwhelming emotion came out gradually, first in abstract paintings, a series called Yishen, and eventually in an installation Gone With the Wind.

The Chinese have a concept, the term "Yishen" which literally means " to abandon the body". Such immolation was historically documented in China.

But before the present century, Tibetans had no such concept - it was not known before and due to their acute situation of suffering from the Chinese repression, the sudden practices of self immolation -- as an expression of suffering.

AH: what you are saying is very Buddhist attitude. Sonam is not expressing that the self -immolations were insurgence or defiance, but that they were the expression of the suffering of the people and that is why they did it. Sonam also explained that it is difficult to find the words and this is why the artistic expression conveys the thoughts. She relies on objects to convey the thoughts since the words are difficult to find.

For example: the installation of the "Fullness- Hunger play of my childhood" in 2017. Here Sonam made sculptures which look like bones of spine, the sculptures are actually 3D prints of real bones, enlarged maybe 100 times. One side is convex (= full) and the other side, concave (= hungry). For Sonam, at the same time she is thinking of her own life- where at times she has experienced great hunger -- also thinking of of our world in which so many people are hungry and dying due to lack of good food but others are having all the time too much and wasting the food they have. The inspiration came in part from her childhood where the children play " the bone game" which was a bit like rolling dice.

AH: Another installation was shown in Le Noirmont (Switzerland) The merry-go-round, 2018. Sonam's caption (www.sonambrauen.net/installations) reads

The merry-go-round of profits turns eternally

Similar to a wheel of fortune;

Like a Tibetan prayer wheel.

Ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

In this installation, there is a carrousel turning with the black tuxedo jackets and white shirts.

SDB: The black - emblem of rich and fancy celebrations black tie/ white collar - somehow symbolic of power and money issues in the world -- as if all is black and white in this situation of power and poverty . It is not all equal - there is much unfairness.

AH: so the carrousel turns and the round of profits has its ups and downs, eventually likened to the death which is inevitably part of life, thus the notion that these garments will all be gone when the life of the people is over - that they will be dead and cremated thus becoming ashes - the black -tie garments of the rich are the expression of the temporary state of great wealth and how the transience of human existence is such that this will all become ashes eventually...

Sonam's focus on this idea of impermanence comes in another installation assembled from human hair forming a five pointed star entitled "In Foreign Climes " , 204 - 250 x 60 cm. The image of this very large star formed of human hair of many colors, piled so high. This also reflects the transience of human existence. In fact, Sonam went to hairdressers, and there she was able to gather the hair. (https://www.sonambrauen.net/in-foreign-climes)

AH : another large installation was titled Boomerang (2010), 300 x 280 cm. Here you made a creation using ammunition shells - this was in order to transform the concept of the ammunition shells ?

SDB: I feel devastated because of the extensive use of weapons, but what to do , how can a small woman feeling the devastation by arms - feeling for the defenceless - do something ? The idea grew slowly to form a boomerang with many amunition shells – I feel the meaning of it is self-evident.

AH : practically speaking, how did you proceed to get the shells ??

SDB: I found a shooting range in Manhattan but I had to spend a whole day going through the waste container to make all the ammunition of the same size - I was going slowly as if I found a gold mine - to get the same format it was a full day of sorting and working - then hours to bring to my home. I was so preoccupied with my quest that I was completely overwhelmed but so happy to find the objects which could correspond to the artistic need - the next day I was sick.

SDB: This piece, Boomerang, was given the World Citizen Artist prize in 2018 --

I am shy in life but in my art, this brings out the side of determination to be able to express these concerns about suffering, about defenceless people, about the transience of power and riches as well as the transience of human existence ....

SDB: My work, it is slow in gestation and uncertain path at first but during the long period, slowly the object comes which can express aesthetically the concern, the concept...

for example, in my painting series of 2017, The Abschied - The Farewell, this was made as my mother was leaving for Lhasa -- it is her departure to Tibet but also perhaps her departure for ever -- would she return or no ??? In these canvas some people say one can see the silhouette of my mother doing the Tibetan walk of prosternations on a hill but for me it is just the abstract, the aesthetic aspect.

Also in my painting series of 2010, there had been a giant oilspill in Gulf of Mexico - much life in the oceans of plants and of fishes - all had been destroyed due to the oilspill. I thought of the oceans - and I was crying as I was painting the Silent Ocean series - nearly monochrome - little color, no movement, like the oceans which became silenced due to the oilspill depriving all life of oxygen - but the vision of these paintings gives a great sense of depth - of the ocean itself and the deepness of the ocean is visible - after painting I was crying first but then I felt lighter after painting.

Bibliography

Benn, James. Burning for the Buddha, Self immolation in Chinese BuddhismUniversity of Hawaii Press, 2007.

Brauen, Martin (ed.) The Dalai Lamas A Visual History, 2005, Serindia and Arnoldische publishers.

Colorado University Art Museum, Waves on the Turquoise Lake: Contemporary Expressions of Tibetan Art, curated by Lisa Tamaris Becker and Tamar Victoria Scoggin. Colorado University Art Museum and Mechak Center for Contemporary Tibetan Art, Boulder, 2006.

Doran, Anne. "Tibet 2.O A New contemporary art show asks what it means to be Tibetan" (review of Transcending Tibet exhibition) April 1, 2015, Tricycle: https://tricycle.org/trikedaily/tibet-20.

Gade, "The Present-Progressive of Tibetan Art" in exhibition catalogue Transcending Tibet, Paola Vanzo, Davide Quadrio, Trace Foundation and Arthub, New York, 2015: 82-84.

Gade and Sweet Tea House, Tsesung Lhamo, "A Broken Flower Blossoming in the Cracks: Tibetan artist Gade talks about Contemporary Tibetan Art" interview 2016 (first published on wechat Sweet Tea House, July 29, 2016, and translated by High Peaks, Pure Earth, August 23, 2016. https://highpeakspureearth.com/2016/a-broken-flower-blossoming-in-the-cracks-tibetan-artist-gade-talks-about-contemporary-tibetan-art.

Gonkar Gyatso, "Abstract IATS 2016, Tibetan art and Tibetan identity " unpublished (november 2015).

Harris, Clare. The Museum on the Roof of the World, Chicago, 2012.

Harrison, Paul. "Notes on some West Tibetan manuscript folios in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art," Pramāṇakīrtiḥ, Papers Dedicated to Ernst Steinkellner on the Occasion of his 70th Birthday. Part I. editors: B. Kellner, H. Krasser, H. Lasix, M. Much, and H. Tauscher, Wien, Wiener Studien zur Tibetologie und Buddhismuskunde 70.1, 2007: 229 -245.

Heimsath, Kabir Mansingh, "Untitled Identities, Contemporary art in Lhasa ,Tibet", December 16, 2005, Asianart.com: https://www.asianart.com/articles/heimsath/index.html#18.

Heimsath, Kabir Mansingh, “Canvas Lucida” in Tsewang Tashi, Untitled Identity, Rossi and Rossi, London, 2009: 8-17.

Heller, Amy and Charlotte Eng, "Three Ancient manuscripts from Tholing in the Tucci collection, ISIAO, Roma, Part, II. Ms. 1329 O." Interaction in the Himalayas and Central Asia: Processes of Transfer, Translation and Transformation in Art, Archaeology, Religion and Polity. editors: E. Allinger, F. Grenet, C. Jahoda, M.-K. Lang, A. Vergati. Vienna, Austrian Academy of Sciences. 2017: 173-190.

Hessel, Elke. "Untamed Encounter" in Stephan v. d. Schulenburg, Elke Hessel, Karsten Schmidt, Matthias Wagner K. (eds.) Buddha 108 Encounters, Museum for Applied Arts Frankfurt (museumangewandtekunst), Wienand verlag, Cologne, 2015.

McGranahan, Carole and Losang Gyatso, "Seeing into Being: The Waves on the Turquoise Lake Artists and Scholars’ Symposium", 2007.

Miller, Leigh. "Inside Out exhibition, May 20-22, Lhasa (2007)", essay and photographs of exhibition published on Leigh Sangster blogspot, http://leighsangster.blogspot.com/2007/05/inside-out-exhibition-may-20-22-lhasa.html?m=0.

Miller Sangster, Leigh. "Meeting Old Buddhas in New Clothes" introductory essay to Tibetan Encounters - Contemporary Meets Tradition, exhibition catalogue, Rossi and Rossi, London, March 2007: 5-11. (see also http://leighsangster.blogspot.com/2007/01/tradition-meets-contemporary-essay.html?m=0).

Miller, Leigh. "Transcending Tradition, Transcending Borders", in Paola Vanzo and Davide Quadrio, Transcending Tibet, exhibition catalogue, Trace Foundation and Arthub, New York, 2015: 40 -57.

PWContemporary "Tsewang Tashi", https://www.asianart.com/pwcontemporary/gallery2/1.html.

Reynolds, Valrae and Amy Heller, Catalogue of The Newark Museum Tibetan collection, vol. 1. 1983.

Reynolds, Valrae. Tibet A Lost World. New York, Federation of the Arts, 1978.

Rossi, Fabio "Preface" in Tsewang Tashi, Untitled Identity, Rossi and Rossi, London, 2009.

Tsewang Tashi, Untitled Identity, solo exhibition 29 October -26 November 2009, Rossi and Rossi, London, 2009.

Tsewang Tashi, Modernism in Tibetan Art, The Creative Journey of Four Artists, PhD. dissertation, Technical University of Trondheim NTNU, Norway, 2014.

Tsewang Tashi, "Twentieth Century Tibetan Painting" R. Barnett and R. Schwartz, Tibetan Modernities, Notes from the Field on Cultural and Social Change, Brill Publications, 2008: 251 -266.

Vanzo, Paola and Davide Quadrio, Transcending Tibet, Trace Foundation and Arthub, New York, exhibition catalogue March 14 - April 12, 2015.

Watt, Jeff. "Painting. Photo Realism Main Page" Himalayan Art Resources, written in October 2015 and updated June 2017, see: https://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=4202 has).

Yao, Jasmine, "A Talk with Gonkar Gyatso on Identity" in The Emory Wheel, Nov. 17, 2016, https://emorywheel.com/a-talk-with-gonkar-gyatso-on-identity.

HOME | TABLE OF CONTENTS | INTRODUCTION

Articles by Amy Heller

asianart.com