Thirteenth or Eighteenth Century?

A response to David Weldon’s “On Recent Attributions to Aniko”

(asianart.com, October 21, 2010)

by Michael Henss

text and photos © asianart.com and the author except as where otherwise noted

February 14, 2011

This article is a rejoinder to the article by David Weldon, "On Recent Attributions to Aniko"

Please click here for a forum on this subject where you can post your views and impressions on the subject of Aniko attributions.

(click on small images for large images with captions)

It is my opinion that Nepalese and Tibetan art of the 13th and 14th century was influenced considerably by Indian Pala style models in a great variety of forms and atelier traditions. However, a closer look at all these “Pala-Newari” and “Pala-Tibetan” or Nepalo-Tibetan artistic traditions will naturally help identifying specific stylistic groups beyond a simple Pala pattern which I feel characterises – in different degrees – the great majority of “Himalayan” art works of that period.

When emphasising “more the Indian content” of the Cleveland Green Tara (fig. 13; Weldon, fig.1) as David Weldon does with regard to some earlier Pala period elements in that painting, he clearly underestimates the distinctive Nepalese profile of this masterpiece datable on stylistic grounds to the third quarter of the 13th century. No comparable 13th century Indian paintings exist which could have served as models or to some extent as a source of inspiration.

Fig. 2 |

Fig. 3 |

Fig. 4 |

Fig. 5 |

The only other - and in my opinion approximately contemporary - Newar paintings of a similar - though not of the same - individual style as the Cleveland Tara are the three Tathagatas in the Boston, Los Angeles and Philadelphia museums (Weldon, fig.6). These paintings find close parallels or rather reflections among the sixteen large mandala paintings in the Changma temple (Lha khang byang ma) at the Great Sutra Hall in Sakya executed after 1280 by no doubt Nepalese artists. These murals are in some sections originally preserved but so far are quite unknown. [1] They are in composition and stylistic details so closely related to the slightly later mandalas at Shalu that they can be with some probability attributed to the same atelier. As Weldon rightly suggests, there would be no need to construct for these Shalu paintings, as hitherto has been done, an art historical detour via the Yuan China art milieu at Beijing. [2]

Fig. 6 |

However, whereas Weldon accepts the possible authorship by Aniko for the Cleveland Tara (as Kossak and I have suggested some years ago), he rejects unconvincingly any further attribution to what might be called an “Aniko style” in the sense of an atelier tradition or a related group of some roughly contemporary or slightly later sculptures.

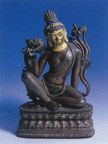

Weldon’s analysis of four images he borrowed from my book [3] leaves out eight more statues that were documented in my more detailed papers from 2006 to 2009. [4] Weldon seems to follow the motto “What is not known (or recognised yet) cannot exist” when he declares them all briefly and without proper arguments as being “made in a revivalist style for Tibetan patrons…of 18th century at the earliest”. But most of them in fact date to the 13th century such as for example the Newark (fig. 1) and Lhasa (figs. 5,6) Avalokiteshvaras or the two Vajrapani statuettes in the Philadelphia and Lhasa museums (figs. 8, 9), all of a very distinctive style with decorative inlays, which by no means can be regarded as 18th century copies. [5] A similar Nepalese copper image of a bodhisattva Maitreya with gold and silver inlays preserved in the Potala Palace is another addition to the small "corpus" of the "Aniko style group" comparable with the Lhasa Avalokiteshvara in material, metal inlay (though slightly less refined), design of the lotus throne and of its petals. (fig. 7) [6] One may also note a Nepalese Vajrapani statue once in the Ford Collection, Baltimore, which indeed “does not conform to any regional convention that has yet been identified” [7]

Fig. 7 |

Fig. 8 |

Fig. 9 |

Fig. 10 |

With few exceptions Tibetan stylistic copies of earlier prototypes from Kashmir, Pala India or Nepal made in the 18th century can be recognised by a trained eye relatively easily. However, very refined metal inlays [8] (figs. 1, 8, 9) reflect earlier contemporary Indian and Newari painting style textile patterns as seen in the Cleveland painted Tara and San Francisco Green Tara kesi and cannot be attributed to the 18th c [9]. How Indian Pala style models were transformed into “Indo-Nepalese” as well as “Indo-Tibetan” statuary of a closely related stylistic physiognomy may be shown by two ca. mid-13th century bodhisattva images in the Beijing Capital and Palace Museums (fig. 3) [10]

Fig. 11 |

Fig. 12 |

Fig. 13 |

Fig. 14 |

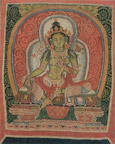

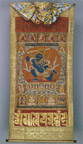

Weldon also misinterprets the San Francisco Green Tara Kesi (fig. 12; Weldon, fig.15 [11], which in proportions and design is without any doubt clearly associated with the Cleveland Tara (fig. 13) and other Nepalese paintings of that period, no matter if woven around “1295” or “1315”. Indeed this textile is the sole representative of the famous textile image production supervised by Aniko at the Yuan court. And the ornamental vocabulary as referred to by Weldon with regard to other 14th century kesi such as the Metropolitan Museum Vajrabhairava mandala does not change from one decade to the other, especially in fabric images which are often manufactured much later than their painted models: like for example the well known early 14th century kesi Acala in the Lhasa Tibet Museum (fig.14) which is, in my opinion - in contrast with the usually suggested Xixia Tangut origin - a later woven reproduction of an early 13th century Tibetan painting. The kesi was probably made in the imperial Yuan dynasty ateliers in Hangzhou and sent to Tibet in the late 13th or early 14th century. [12] A production of the Acala kesi around 1300 would be supported by the following arguments: the floral ornament and the lan dza sript frieze on the original(!) fabric border do not exist much before 1300. The pearls stitched on the figures in the lower register (only one is preserved) indicate a Mongolian period origin. And some linguistic inconsistencies in the Tibetan inscription point out to a later non-Tibetan textile atelier. So what does it matter for our stylistic considerations in view of an “Aniko style” (which no doubt did exist!) whether this kesi was made in the late 13th or earlier 14th century? And how do Pala style forerunners such as the Potala Green Tara (Weldon fig.14) rule out a “Newar-Tibetan” sculptural style, which is based anyway, like so many other Himalayan statuary traditions, on earlier Pala prototypes?

Fig. 15 |

Fig. 16 |

Fig. 17 |

Fig. 18 |

Unfortunately Ulrich von Schroeder’s “Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet” (Hongkong 2001) does not include sufficiently later Nepalese and Tibetan statue traditions, and no images of a genre as reviewed here, of which, however, examples may still exist in Sakya monastery or in the Potala Palace collection.

Other attributions to Aniko or to his style such as the Maitreya painting in the Chicago Art Institute (Weldon fig.7) or of the gilt silver Sadaksari-Avalokiteshvara in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (Weldon fig.10) are rightly rejected by Weldon. A thorough analysis will easily identify both images as much later syncretistic replicas where floral ornaments and figural style (painting) or the design and technique of the gilt lotus petals (statue) alone rule out a Yuan dynasty date. And those misleading attributions and chronologies by John Huntington have not been the only ones in his otherwise comprehensive and inspiring publications [13]

Further studies after my publications in 2007-2009 suggest, however, that the attribution of two very similar statues to the "Aniko style group" has to be reconsidered. The Green Tara statuettes in the Potala Palace and in the Tibet Museum at Lhasa appear to be stylistic copies of the 18th century, both compared with other revivalist images of a highly refined quality and made in an extraordinary "authentic" style (fig. 15,16). [14]

With reference to David Weldon’s summary at the end of his review and to my recent attribution of some still existing figural and decorative metalwork to Aniko such as the upper part of the repoussé throne-back-nimbus (gdan khri rgyab yol) commissioned in 1261/62 according to the Fifth Dalai Lama’s dKar chag by Sa skya bZang po, “the principal of the Sakya leaders” in the 1260s, mentioned as made “by the Nepali A ni ka gui gung la”, and the architectural bracket system of the canopy-baldaqin enshrining the Jowo Shakyamuni image in the Lhasa Jokhang temple [15] I hope that this response may contribute to a less confusing picture of what the “Aniko style” may have been like.

Michael Henss

December 23, 2010

Please click here for a forum on this subject where you can post your views and impressions on the subject of Aniko attributions.