N o t e

s

1. See M.Henss, The

New Tibet Museum in Lhasa. Orientations, February 2000, p.62-65

2. See M.Rhie/R.Thurman,

Wisdom and Compassion. The Sacred Art of Tibet. New York 1991 and 1996

(German ed. 1996); P.Pal (Ed.), Himalayas. An Aesthetic Adventure. Chicago

and Berkeley 2003.

3. See The Bowers

Museum of Cultural Art (Ed.): Tibet – Treasures from the Roof of

the World. Santa Ana 2003, and a review by Terese Tse Bartholomew in:

Orientations, October 2003, p.65-67. Trésors du Tibet. Région

Autonome du Tibet, Chine. Paris 1987; Tesori del Tibet. Oggeti d’arte

dai Monasteri di Lhasa. Milano 1994 (exhibits from public institutions

in Lhasa; text by E. Lo Bue).

4. p.122. See Kah-thog

Si tu Chos kyi rGya mtsho (1880-1925): Gangs ljongs dbus gtsang gnas bskor

lam yig nor bu zla shel gyi se mo do (An Account of a Pilgrimage to Ü-Tsang

in the Land of Snows entitled Necklace of Moon Crystal), Palampur 1972,

p.156ff.

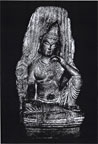

5. U.von Schroeder,

Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet. Hongkong 2001, vol.II, p.972ff.: “after

1495”.

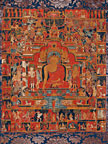

6. This Lamdre cycle

recalls the wellknown painted Ngor-Sakya lineage series of probably once

34 thangkas (over 20 have survived in Western public and private collections)

from Buddha Vajradhara until the 14th Ngor abbot Nam mkha’ dpal

bzang (r.until 1595, d.1603) dating to around 1600, of which the first

eighteen images are iconographically identical with the Mindröl Ling

statues. This is based on an unpublished preliminary list reconstructing

this thangka series by David Jackson (1996) and on the identification

of the last lama in the set, the 14th Ngor abbot, by Amy Heller in: Himalayas.

An Aesthetic Adventure 2003, op.cit., p.295).

7. von Schroeder

2001, op.cit., p.771-791, plate 185 A-B, see for a discussion of his “Zhang

zhung arguments” and for some serious doubts about a Buddhist (!)

art production in a “Zhang zhung Kingdom of Western Tibet”

M.Henss, Review Article on “Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet”

by U.von Schroeder(Hongkong 2001, in Oriental Art, no.2/2003 (p.49-60),

p.55-56.

8. von Schroeder

2001, op.cit., p.778-791 and p.741-769. On Khyung lung and Zhang zhung

see also M.Henss, Notes on Khyung lung in Ancient Zhang zhung, Western

Tibet. In: Studies in Sino-Tibetan Art. Proceedings of the Second International

Conference on Tibetan Archaeology and Art, Beijing, September 3-6, 2004,

Beijing 2006, p.1-26.

9. Compare for example

Huo Wei/Li Yongxian, The Buddhist Art in Western Tibet. Chengdu 2001,

fig.193 (Western Tibet), 195 (Kashmir). See M.Henss, Buddhist Metal Images

of Western Tibet, ca.1000-1500 A.D.: Historical Evidence, Stylistic Consideration,

and Modern Myths. The Tibet Journal, vol.XXVII, no.3/4, 2002, p.23-82.

The Buddha image no.14 was already published in: Jinse Baozang. Xizang

lishi wenwu Xuancui, Beijing 2001, p.146f.

10. See P.Pal, Himalayas

2003, op.cit., no.62, 68; Priceless Treasures. Beijing 1999, no.26.

11. See R.Goepper.

Alchi. Ladakh’s Hidden Buddhist Sanctuary. The Sumtsek. London 1996.

12. See Rhie/Thurman

1996, op.cit., no.171 (“Central Regions, Tibet”), and for

the certainly later Pala style Maitreya at sNye thang M.Henss, Himalayan

Metal Images of Five Centuries: Recent Discoveries in Tibet. Orientations,

June 1996, fig.20.

13. While the extensive

discussion on the “Indian” or “Tibetan” origin

of the Green Tara in the Ford Collection (Baltimore) is certainly a delicate

issue (although in my opinion being more in favour of an Indian artist),

at least a fragmentary 11th century painted scroll of the debating Maitreya

and Manjushri found in Tibet must be attributed with much likelihood to

an artist from India, see Tibet. Arte e spiritualità, ed. by S.B.Deotto,

Milano 1999, plate p.101, and S.Kossak, Pala Painting and the Tibetan

Variant of the Pala Style, The Tibet Journal, vol.27, 3/4, 2002, p.6,

fig.6.

14. See N.R.Ray,

Eastern Indian Bronzes. Delhi 1986, plate 282 and 312.

15. Compare for other

metal statues of this type and style D.Welden/J.Casey Singer, The Sculptural

Heritage of Tibet. Buddhist Art in the Nyingjei Lam Collection. London

1999, pl.11; von Schroeder 2001, op.cit., pls.167, 217-220; Qing Gong

Zangchuan Fojiao Zaoxiang (Tibetan Buddhist Sculptures in the Palace Museum),

Beijing 2003, pl.83.

16. See for a detailed

discussion M.Henss, King Srong btsan sGam po Revisited: The royal statues

in the Potala Palace and in the Jokhang at Lhasa. Problems of historical

and stylistic evidence. Essays on the International Conference on Tibetan

Archaeology and Art, Beijing 2002, Chengdu 2004 (p.128-171), p.132ff.

17. von Schroeder

2001, op.cit., p.940.

18. Compare also

for further ca.14th „princely“ statues in the Potala Palace

von Schroeder 2001, pl.312 A-C; Henss 2004, op.cit., fig.20.

19. See for other

contemporary gilt copper images by Newari artists in Shalu monastery von

Schroeder 2001, pls.229 A-C, 230 A-C, 231 A and B.

20. See Kah thog

Si tu 1972, op.cit., p.413.

21. See S.K.Pathak,

The Album of the Tibetan Art Collections. Patna 1986, pls.5,6, 7,11 (photographed

by the Indian scholar R.Sankrityayana on his travels in southern Tibet

between 1929 and 1938). According to my knowledge circa 20 painted scrolls

of this tathagatha type dating to the 12th and 13th century have survived

in public and private collections, not including the later versions of

the 14th century.

22. See C.Bautze

Picron, Sakyamuni in Eastern India and Tibet from the 11th to the 13th

centuries, in: Silk Road Art and Archaeology, vol.4, Kamakura 1995/96,

fig.2, 3, 18; P.Pal, Art of the Himalayas. New York 1991, no.81; S.Kossak/J.Casey

Singer, Sacred Visions. Early Paintings from Central Tibet. New York 1998,

no.27; P.Pal (Ed.), Himalayas 2003, op.cit, no.121; Xizang Yishu (vol.Painting),

Shanghai 1991, p.143; Xizang Yishu Jicui (A Selection of Tibetan Art,

Taipei 1995, fig.316, all depicting Shakyamuni without crown, and usually

flanked by the white Avalokiteshvara and the gold- or yellow coloured

bodhisattva Maitreya (or in a few cases by the two disciples of the Buddha),

an iconographic standard already at the Bodhgaya Mahabodhi temple in the

7th century (see Xuanzang’s report, S.Beal, ed..)l: Si-Yu-Ku. Buddhist

Records of the Western World, London 1884, reprint Delhi 1981, II, p.119),

symbolizing compassion (karuna) and friendliness (maitri), are also mentioned

in relation with the Mara episode in the Lalitavistara Buddha biography.

– See for another 15th century Nepalese painting of this iconographic

type P.Pal, Arts of Nepal, vol.II, Leiden 1978, pl.204, and J.Casey Singer,

Bodhgaya and Tibet, in: Bodhgaya . The Site for Enlightenment, ed. by

J.Leoshko, Bombay 1988, pl.14. – For the “Vajrasanasana tathagata”

as described in several sadhanas see M.Th.de Mallmann, Introduction à

l’iconographie du Tantrisme Bouddhique, Paris 1975, p.418.

23. J.Huntington,

Leaves from the Bodhi Tree. The Art of Pala India (8th-12th century) and

its International Legacy. Seattle 1990, p.105f.

24. S.Beal, (Si-Yu-Ki)

1884, op.cit., vol.II, p.121.

25. J.Leoshko, The

Vajrasana Buddha, in: Bodhgaya – the site of enlightenment, ed.

by Janice Leoshko, Bombay 1988, p.41. Leoshko suggests that the concept

of the crowned Buddha is probably emphasizing the connections rather than

the distinctions between the historical Buddha Shakyamuni and the notion

of Buddhahood as embodied by the “ahistorical” transcendental

Buddhas.

26 R.Kaschewsky,

Das Leben des lamaistischen Heiligen Tsongkhapa Blo Bzang Grags pa (1357-1419),

dargestellt und erläutert anhand seiner Vita “Quellort allen

Glückes”, Wiesbaden 1971, p.165.

27 In how far the

scenes around the central Mahabodhi Buddha composition may refer to the

tradition of the Buddha’s legendary Kalacakra teachings in the Dhanyakataka

Stupa (see p.179 and 594, n.101) would deserve a proper iconographic analysis

of this interesting thangka.

28 Based on von Schroeder

2001, op.cit., vol.I, p.328-337, according to whom this wooden replica

must have been made in order to “serve as a model for the construction

of a Mahabodhi-type temple at another location”, a hypothesis, which

however would not correspond so well to the fact, that the object was

once brought – as a sacred reliquary – to Tibet, though it

cannot be ruled out that it was given to the new land of the Buddhist

faith only sometime after circa 1200, when there was no more much need

and use for keeping such architectural models for new constructions in

the heartland of the Buddha and beyond.

29 Precious Deposits,

Historical Relics of Tibet, China. Beijing 2000, vol.I, p.108-112; Sha

jia si (Sakya Monastery), Beijing 1985, fig.105. The illuminated Pala

manuscript was shown to me in 1994.

30 E.Steinkellner,

A Tale of Leaves. On Sanskrit Manuscripts in Tibet, their Past and their

Future. Eleventh Gonda Lectures 2003, Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts

and Sciences, Amsterdam 2004, p.30.

31 R.Sankrtyayana,

Second Search of Sanskrit Palm-Leaf Manuscripts in Tibet. Journal of the

Bihar and Orissa Research Society, vol.XXIII, 1937 (p.1-57), p.4-6. For

several illuminated Indian Pala manuscripts photographed in the 1930s

in Tibetan monasteries such as Ngor, Narthang and Sakya see S.K. Pathak

1986, op.cit., plates 19-29.

32 See for a drawing

after this painting M.Henss, review article of “Sacred Visions”.

Early Tibetan Painting” (New York 1998), Oriental Art, 4/1998-1999,

fig.1, and fig.2 for a sPu rgyal period painting depicting a standing

monk.

33 See Kossak/Casey

Singer 1998, op.cit., no.1. Comparable in both 11th century paintings

are the proportions of the head, facial features, nimbus, design of the

lotus base, and donor figures.

34 Like some other

scholars (see for example Bartholomew 2003, p.66f.) Per K.Sorensen, (Rulers

on the Celestial Plain. Ecclesiastic and Secular Hegemony in Medieval

Tibet. A Study of Tshal Gung- thang. 2 vols. Wien 2007, vol.II, p.353ff.),

focusing strongly on the pre- and early Mongol Sakya-Tangut relations

in the 12th and 13th centuries and especially on the “Xi Xia Tshal

Gung thang connection” during the first half of the 13th century,

associates this “patronized tapestry tradition” like the Lama

Zhang kesi in the Lhasa museum and some other related fabric images quite

definitively and in great detail with the Xi Xia Tangut Kingdom (Tib.

Mi nyag), where it would have been manufactured and then “presented

to Grags pa rGyal mtshan” between circa 1200 and 1216.

35 See for example

a 13th century Acala painting in Kossak/Casey Singer 1998, op.cit., no.22

(“ca.1200), which also would support a later 13th century date for

the Acala kesi, whose overall style may hardly predate the painted models.

36 Sorensen 2007,

op.cit.: “it is more than likely that the Acala was presented to

Grags pa rgyal mtshan as a token of respect in connection with or on the

occasion of some consecration ceremonies of Cang ston”.

37 M.Henss, The Cultural

Monuments of Tibet. The Central Regions, forthcoming, vol.I, ch.I.9 forthcoming.

38 For this information

I have to thank Bernadette Bröskamp.

39 Compare for example

a similar design of a later Yuan fabric thangka in the Lhasa museum, Precious

Deposits 2000, op.cit., vol.III, no.22.

40 Similar red and

blue silk panels “brocaded in flat gilded paper” have been

dated to the 13th century (see: J.Simcox, Chinese Textiles, London 1994

Spink and Son Ltd., no.14) or were used also for top and bottom mounts

on a 13th century Song kesi of a Buddhist image in the Potala Palace (see:

Great Treasury of Chinese Fine Arts, vol.6, Shanghai 1987, pl.193). Another

lan dza script panel of this type and technique was carbon-14 “dated”

to 1439-1629 (see: Orientations, February 2000, p.35). Yet how problematic

and misleading these tests can (!) be, is shown in a professional catalogue

of a textile exhibition, where several Tibeto-Chinese silk brocades and

kesi weaves were dated a hundred years earlier (or even “with 95%

confidence A.D.980-1290”, advertisement Spink and Son Ltd, Orientations,

August 1989) than they were in fact produced by iconographic and stylistic

evidence (see: Heaven’s Embroidered Cloths. One Thousand Years of

Chinese Textiles, Hongkong 1995, no.21-22 h).

41 Sorensen 2007,

op.cit.

42 After: Tapestry

in the Collection of the National Palace Museum (Taipei), Kyoto 1970,

p.16, with a good survey on the kesi technique and it’s history

(p.11-17).

43 Su Bai, Yuandai

Hangzhou de Zangchuan Fojiao Siyuan Kaogu (On Tibetan Buddhism in Hangzhou

in the Yuan dynasty and some related cultural relics), in: Su Bai, Zangchuan

Fojiao Siyuan Kaogu (Archaeological Studies on Monasteries of Tibetan

Buddhism, Beijing 1996 (p.365-387), p.376f.

44 A reproduction

of the Tsethang Yongle Cakrasamvara was already published in the picture

album A Survey of Tibet, Lhasa, 1987, and in M.Henss, The Woven Image:

Tibeto-Chinese Textile Thangkas of the Yuan and Early Ming Dynasties,

Orientations, November 1997, fig.11.

45 Henss 1997, op.cit.,

fig.9, 10. When these two banners were shown upon my personal request

in 1994 I was sadly unable to make detailed photographs and thus could

not identify the lamas and their specific lineage in the upper register.

46 See A.Heller,

Tibetan Art. Milano 1999, p.88, plates 75, 76.

47 For the blue Vajrabhairava

brocade image see: The Potala. Holy Palace in the Snow Land, Beijing 1996,

p.151. The Jokhang banner is unpublished.

48 Bod kyi thang

ka (Tibetan Thangkas), Beijing 1985, pl.5; Henss 1997, op.cit., fig.12.

49 See Christie’s

New York, 2.6.1994, no.225.

50 See for the Hevajra

kesi: The Potala Palace 1996, op.cit., p.145. For the private collection

Hevajra embroidery see A.Heller, A Yung-Lo Embroidery Thangka: Iconographic

and Historical Analysis. Sino-Tibetan Buddhist Art Studies. The Third

International Conference on Tibetan Archaeology and Arts, Beijing 2006,

Abstract.

51 Ming shilu, ed.

Beijing 1974, juan 331, p.8577; E.Sperling, Early Ming Policy toward Tibet:

An Examination of the Proposition that the Early Ming Emperors adopted

a “Divide and Rule” Policy toward Tibet. Phil. Thesis, Indiana

University (USA) 1983, p.136ff.

52 See Henss 1997,

figs.7,12,15,16,18; The Potala Palace 1996, op.cit., p.145; E.Lo Bue in:

Tesori del Tibet, Milano 1994, no.81. While during his first visit at

the imperial court in Nanjing (arrival on February 3, 1415) Shakya Yeshe

had received the title of a “State Teacher” or “Great

National Preceptor” (da guo shi) by the Yongle emperor, the more

honorofic title of a “Great Compassionate Dharma King” (daci

fawang), of which “Jamchen Chöje” (Byams chen chos rje)

is a Tibetan variation (E.Sperling 1983), was only granted on his second

visit in Beijing in 1434 by the Xuande emperor. For references see: Ming-shih,

juan 331, p.8577, Beijing 1974; G.Tucci, Tibetan Painted Scrolls, Roma

1949, p.253 and note 62; T.W.D.Shakabpa, Tibet. A Political History, New

Haven/London 1967, p.84; T.V.Wylie, Lama Tribute in the Ming Dynasty,

in: Tibetan Studies in Honour of Hugh Richardson, ed. by M.Aris/Aung San

Suui Kyi, Delhi 1980, p.107; E.Sperling, The 1413 Ming Embassy to Tsong

kha pa and the Arrival of Byams chen Chos rje Shakya Ye shes at the Ming

Court. Journal of the Tibet Society, vol.2, 1982, p.107; E.Sperling ,

Early Ming Policy toward Tibet: An Examination of the Proposition that

the Early Ming Emperors Adopted a “Divide and Rule” Policy

toward Tibet. Phil.Diss. Indiana University, USA, 1983, p.149ff. (in 1415

“Ch’eng tsu did not make Shakya ye shes a fa wang”,

but only a “guoshi”); Sera Thekchen Ling, Beijing 1995, introduction;

and last but not least the inscriptions on the two wellknown kesi and

embroidery portraits of this lama in the Tibet Museum, Lhasa, see Henss

1997, op.cit. (see here note 44), figs. 15,18. With regard to Amy Heller’s

research on a comparable Hevajra embroidery in a private collection I

can refer here only on my own photographs of this very thangka and on

Heller’s presentation of her paper (and on the abstract) at the

Third International Conference on Tibetan Art and Archaeology in Beijing,

October 2006, but not on the complete text of this paper to be published

in the Proceedings of this conference (forthcoming). An attribution of

the latter embroidery to the Yongle emperor and thus to 1415 or the years

after Shakya Yeshe’s first visit to the imperial court would be

confirmed only by the “lower” title of a daguoshi in the inscription

on the back (presently unknown to me), while the title “Jamchen

Chöje” (Byams chen Chos rje) was only bestowed upon the Sera

founder later on and probably not before his second visit at the court

in 1434/35, which means by the Xuande emperor (see Sperling 1983, op.cit.,

p.149ff).

53 The sumptuous

ornamental vocabulary of the Potala Hevajra recalls comparable fabric

thangkas of the 1434/1435 period such as Henss 1997, fig.7,16,18, or the

private collection Hevajra embroidery, which probably belongs for iconographic

and stylistic reasons (Byams chen Chos rje in teaching gesture, formal

affinity to the Metropolitan Museum, Vajrabhairava) to the late “Xuande

group” of circa 1434/1435.

54 See for a brief

modern survey on the Yongle and Xuande gilt copper statues also the Sotheby’s

catalogue Visions of Enlightenment. The Speelman Collection of Important

Early Ming Buddhist Bronzes, Hongkong 7.10.2006, with an introduction

by David Weldon and detailed texts for 15 images in English and Chinese.

– The figure of nearly 300 still existing Yongle and Xuande style

images (with reign mark) is my own estimate. In 2000 I counted in the

Potala Li ma lha khang alone at least 60 statues and another ca. 15 in

the Lhasa Jo khang. A few more are preserved in the Norbulingka Palace

and in the Tibet Museum (Lhasa), and only very few in some monasteries

outside Lhasa.

55 See O.Sirén,

Chinese Sculpture from the Fifth to the Fourteenth Century. London 1925,

reedition Bangkok 1998, vol.II, plate 568. For another Chinese Song dynasty

“model” see E.D.Saunders. Mudra. A Study of Symbolic Gestures

in Japanese Buddhist Sculpture. London/New York 1960, plate XXI and p.130.

56 The other two

(not three) images of this pensive Avalokitshvara are in the Norbulingka

Palace (or now in the Cultural Relics Bureau at Beijing?) and in the Tuyet

Nguyet Collection, Hongkong.

57 Shakyamuni, height

19,5 cm, Christie’s New York 21.3.2001, no.85. Compare for example

with a “pure” Yongle style Shakyamuni in the Palace Museum,

Beijing. Buddhist Statues of Tibet. The Complete Collection of Treasures

of the Qing Palace Museum, vol.60, Beijing/Hongkong 2003, no.212. See

also von Schroeder 2001, op.cit., vol.II, 344 C.

58 Vajradhara, height

30 cm, Christie’s Hongkong 1.5.2000, no.753. Compare for example

with a “pure” Nepalo-Tibetan gilt-copper Vajradhara with inlaid

semi-precious stones in the Jules Speelman Collection, and Sotheby’s

New York 21.9.1995, no.55. In addition to group one and two compare some

Tibetan copies of the Yongle style images: Essen/Thingo 1989, op.cit.,

no.35; H.Uhlig, On the Path to Enlightenment. The Berti Aschmann Foundation

of Tibetan Art at the Rietberg Museum Zürich. Zürich 1995, no.94;

Buddhist Statues of Tibet 2003, op.cit., no.168; von Schroeder 2001, op.cit.,

vol.II, 344 C (?), which may also belong to our group one since inlaid

semi-precious stones – though in fact unusual for Yongle period

statues – were used for Nepalese style images already in the Yuan

period ateliers in Dadu (Beijing), compare for example a Manjushri image

dated 1305, Buddhist Statues of Tibet 2003, op.cit., no.209.

59 Fig. 23: Shakyamuni,

height 16 cm, dated 1426, Palace Museum, Beijing. Iconography and Styles.

Tibetan Statues in the Palace Museum. Beijing 2002, vol.I., no.70; The

twelve(!)-character inscription on this statue “made on March 10,

in the first year of the Xuande [reign]” is however not a signature

of the imperial workshop! - Fig. 22: Shakyamuni, height 18,5 cm, art trade

Switzerland (unpublished). According to Li Jing (Beijing) the inscription

of the latter image has been added in the 18th century due to a minor

variation of the fourth character from left, which would indicate a Qing

dynasty date as it is known for bronze vessels and porcelain.

60 von Schroeder

2001, op.cit., vol.II, p.1246.

61 The Yongle emperor’s

private attachment to Tibetan Buddhism is further very impressively documented

by the famous “Tsurphu Scroll” painting (datable to 1407)

in the Tibet Museum at Lhasa, see Precious Deposits 2000, op.cit., vol.III,

no.48, and D.Berger, Miracles in Nanjing: An Imperial Record of the Fifth

Karmapa’s Visit to the Chinese Capital. In: Cultural Intersections

in Later Chinese Buddhism, ed. by M.Weidner, Honolulu 2001, p.145-169.

See also E.H.Sperling 1983, op.cit., passim; Shih-Shan Henry Tsai, Perpetual

Happiness. The Ming Emperor Yongle. Seattle 2003, p.143f.

62 J.Watt/D.P.Leidy,

Defining Yongle. Imperial Art in Early Fifteenth Century China, New York

2005, p.10.

63 See von Schroeder

2001, op.cit., p.1224-1235; Tibet. Belgrad/Luzern 1981, figs.227-230.

64 See von Schroeder

2001, op.cit., pl.103C and 104C; Precious Deposits 2000, op.cit., vol.II,

no.45 (unknown location in Tibet); and for the most similar Pala prototype:

Iconography and Styles. Tibetan Statues in the Palace Museum, ed. by the

Palace Museum, Beijing 2002, vol.I, no.36.

65 von Schroeder

2001, op.cit., pl.349 B, 351B. – I was able to see two fragmentarily

preserved Yongle style lotus mandalas in the Potala Palace on June 16,

2000. For the information that there would have existed originally a set

of 14 Yongle lotus mandalas I have to thank Prof. Markus Speidel.

A temptative identification

of nine (of originally 14?) lotus mandalas of the “Yongle reign

series”:

1. Lhasa, Tibet Museum (formerly Potala Palace): Vajrabhairava; U.von

Schroeder 2001, 350 A/B

2. Lhasa, Potala Palace: Hevajra; U.von Schroeder 2001, 351 A/B

3. Sakya monastery: Yamari; U.von Schroeder 2001, 349 B

4. Lhasa, Potala Palace: Cakrasamvara; partly shown in the Museum Villa

Hügel exhibition, but not in the catalogue. Unpublished photo by

G.Verhufen

5. Lhasa, Potala Palace; photo M.Henss 1992 and G.Verhufen 2005

6. Lhasa, Potala Palace; photo M.Henss 1992

7. Lhasa, Potala Palace (fragment), recorded by M.Henss 2000

8. Lhasa, Potala Palace (fragment), recorded by M.Henss 2000

9. Ngor monastery: unspecified form of Hevajra (no more extant).G.Tucci,

Tibetan Painted Scrolls. Rome 1949, vol.I, fig.86. A photograph of the

complete mandala exists in the Tucci photographic archives in Rome, Museo

Nazionale d’Arte Orientale, no.6105/24.

66 See The Potala

1996, p.115.

67 D.Jackson, A History

of Tibetan Painting, Vienna 1996, p.222.

68 See Jackson 1996,

op.cit., plate 46.

69 See for over 150

mandala thangkas in the Potala Palace: The Celestial Palace of the Gods

of Tantric Vajra Yana, ed. by the Tibetan Administrative Office of the

Potala, Beijing 2004.

70 In his biography

of the Sixth Dalai Lama Sangye Gyatso mentions that he made 62 medical

thangkas illustrating the Vaidurya sngon po (C.Cüppers, sDe srid

Sangs rgyas rgya mtsho’s vai Duurya g.ya’ sel and the Iconometrical

Handbook cha tshad kyi bris dpe dpyod ldan yid gsos. Sino-Tibetan Buddhist

Art Studies, Third Intern. Conference on Tibetan Archaeology and Arts,

Beijing 2006, Abstracts, p.20).

71 M.Henss, The Cultural

Monuments of Tibet, vol.I, chapter 6.2, forthcoming. For further details

on the medical Thangkas F.Meyer, Introduction à l’étude

d’une série de peintures médicales crée à

Lhasa au 17e siècle, in: Tibet. Civilisation et Société,

Paris 1990, p.29-58, and F.Meyer in Parfionovitch et al.1992. For the

lCags po ri medical school in general: R.Gerl/J.Aschoff, Der Tschagpori

in Lhasa. Medizinhochschule und Kloster. Ulm 2005.

72 For several other

ritual objects of this early imperial Ming style see R.Thurman/D.Weldon,

Sacred Symbols. The Ritual Art of Tibet. New York 1999, nos.62, 63, 64

(with further references) V.Zwalf, Buddhism. Art and Faith. London/New

York 1985, p.210, no.307 (British Museum, with Yongle reign mark); Sotheby’s

London 10.7.1973, no.45 (with Yongle reign mark; said to come from Tsurphu

monastery); advertisement John Eskenazi in Arts of Asia, November 1997;

Sotheby’s London 24.4.1997, no.122; Christie’s New York 17.9.1998,

no.98; Christie’s New York 23.3.1999, no.108; Christie’s New

York 22.3.2000, no.106; Watt/Leidy 2005, op.cit., plate 27 (Metropolitan

Museum of Art, New York; inscribed Yongle nian zhi, “made in the

Yongle era”), see here also p.75,77; Hanhai Autumn Auction, The

Sublime Grandeur of Yongle Imperial Bronzes, Beijing 2006, p.56-71. For

the Khatvanga in the British Museum see also the chapter by John Clarke

in D.La Rocca (Ed.), Warriors of the Himalayas. Rediscovering the Arms

and Armor of Tibet. New York 2006, p.27.

73 Compare Watt/Leidy

2005, op.cit., p.77, with reference to a partially illegible Chinese reign

mark inscription on a ritual axe in the Cleveland Museum of Art.

74 See especially

Zhongguo Zangchuan Fojiao Diashu, vol.4 (A Collection of Tibetan Buddhist

Sculpture. Votif Images in Moulded Clay). Beijing 2001; Xizang Minjian

Yishu Congshu Tuomo Nisu (Tibetan Folk Art Series. Sculptures), Chongqing

2001.

75 See for the whole

problem of Kashmir and western Tibetan statuary M.Henss, Buddhist Metal

Images of Western Tibet, ca.1000-1500 A.D.: Historical Evidence, Stylistic

Consideration and Modern Myths. The Tibet Journal, vol.XXVII, no.3/4,

2002, p.23-82.

76 Bibliographical

reference missing in the catalogue: A.Heller, The Three Silver Brothers.

Orientations, April 2003, p.28-34.

77 See M.Henss, Is

there any “Anige Style” in Nepalo-Tibetan and Tibeto-Chinese

Metal Sculpture of the Sa skya-Yuan Period? Third International Conference

on Tibetan Archaeology and Art, Beijing 2006, Abstracts, p.77-83, and

in: Palace Museum Journal, no.5, 2007, Beijing, p.51-66 (in Chinese) –

I cannot recognize a dragon (Heller) on the lower part of the stele, hower

a serpent instead, which may refer to the year 1293. According to H.Stoddard’s

translation of the inscription the “statue was completed well in

the year of the male water dragon (1292)”, cf. A Stone Sculpture

of mGur mGon po, Mahakala of the Tent, dated 1292. Oriental Art, 1985,

no.3, p.278-282.

78 Though being of

minor importance within this context Luczianits’ (too) early dating

of the mandala wall-painting at Nako monastery in Kinnaur, Himachal Pradesh,

India (fig.4), to the “early 12th century” would not correspond

in my opinion to the Western Tibetan painting styles and to the chronology

of the mandalas at Phiyang (Gu ge, ca.1100?) and Alchi (early 13th century).

79 Compare Precious

Deposits 2000, op.cit., vol.I, nos.72, 87, 88, 100, 103. Other problematic

attribution to the sPu rgyal dynasty period as mentioned by Sonam Wangden

would comprise a text collection on the Potala Palace written by Santaraksita

and some Kanjur and Tanjur texts written in gold script on indigo-blue

paper.

80 Kazuhiro Kawasaki,

On a Birch-bark Sanskrit Manuscript Preserved in the Tibet Museum. Journal

of Indian and Buddhist Studies, vol.52, no.2, 2004, p.903-905. I thank

Dr. Helmut Eimer for having made this publication available. Another very

similar Sanskrit manuscript written on individual birch-bark pages of

the “Indo-Tibetan” palm-leaf type found at Tholing monastery

in Western Tibet confirms for sheer historical reasons an 11th century

date of the Sanskrit book in Lhasa. – A brief comment to note 7

on p.586: the monastery “Drongkhar Chöde” on p.57 of

Sonam Wangden’s text is not identical with “Gongkar Chöde”

(near Lhasa airport), but located in Lhodrag, northwest of Tsona (Tsome).

81 See for example

Mi nyag Chos kyi rGyal mtshan: Srong btsan sgam po’i dus kyi pho

brang po ta la’i bzo dbyibs dang chags tshul skor rob tsam dpyad

pa (A Fundamental Research on the Potala Palace’s structure during

the period of King Songtsen Gampo). Paper presented at the Seventh IATS

Seminar, Bloomington/USA 1998 (unpublished). This author’s arguments

are based on the bKa’ chems ka khol ma, the famous gter ma text

attributed to King Songtsen Gampo and which he regards as authentic. Chos

kyi rGyal mtshan follows largely the hypothesis of the early building

history of the Potala Palace raised in the course of the extensive restorations

in 1989-1994 and published in: Xizang Budala Gong (The Potala Palace of

Tibet). Ed.: Potala Restoration Office. 2 vols. Beijing 1996. For a critical

discussion of the early history and architecture of the Potala Palace

see M.Henss, The Cultural Monuments of Tibet, vol.I, chapter 5.1, forthcoming.

– Several (17th century?) cavity-substructures, between one and

five metres in width and up to 14 metres deep, were discovered at the

Potala in the late 1990s and regarded by Paphen as belonging to the Songtsen

Gampo period (p.38).

82 See Xizang Budala

Gong 1996, op.cit.,p.47, plate 253. For the problem of the earliest building

structures and image cycles on the Potala, especially for the Chos rgyal

sGrub phug chapel, see also M.Henss (King Srong btsan sGam po) 2004, op.cit.,

p.145-149.

83 Gömpojab:

Zaoxiang liangdu jing. The Buddhist Canon of Iconometry. With Supplement.

A Tibetan-Chinese Translation from about 1742 by mGon po skyabs. Translated

and annotated from this Chinese translation into modern English by Cai

Jingfeng. Introduction and editing assistance by Michael Henss, Ulm 2000,

p.13ff., 84.

84 See n.67, and

in the book under review, p.106 and n.16 on p.589. For this identity of

the “second” Grags pa rGyal mtshan see also P.Sorensen, 2007,

op.cit., vol.II, appendix I, n.11.

85 See Shen Weirong:

Studies on the Yuan translation of Bu ston’s Proportional Manual

of the Enlightenment Stupa, in: Studies in Sino-Tibetan Buddhist Art.

Proceedings of the Second International Conference onTibetan Archaeology

and Art, Beijing, September 3-6, 2004, Beijing 2006, p.77-108 (Chinese

text with Bu ston’s text in romanized transliteration); Jackson

1996, p.76 and n.167.

86 C.Cüppers:

sDe srid Sangs rgyas rgya mtsho’s Vaidurya g.ya’ sel and the

iconometrical handbook “cha tshad kyi bris dpe dpyod ldan yid gsos”.

For a more detailed English abstract of this paper see: Sino-Tibetan Buddhist

Art Studies. Third International Conference onTibetan Archaeology and

Art, Beijing 2006, Abstracts, p.19-23.

87 See Gömpojab

2000, op.cit., p.35f. For another English translation compare P.Berger,

Empire of Emptiness. Buddhist Art and Political Authority in Qing China.

Honolulu 2003, p.84ff.

88 Compare Gömpojab

2000, op.cit., ill.p.61, and L.Chandra, Buddhist Iconography of Tibet,

Kyoto 1986, vol.I, fig.90, p.20ff. See also Berger 2003, op.cit., p.87-89,

claiming that according to the original 18th century text edition the

illustrations of the Zaoxiang liangdu jing were “provided as patterns

by Rolpay Dorje” (although this reference remains a bit unclear).

– On Rolpai Dorje’s role in Buddhist art at the Qing court

see M.Henss, Rölpai Dorje – teacher of the Empire. A Profile

of the Life and Works of the Second Changkya Huthugtu, 1717-1786, in:

Chinese Imperial Patronage. Treasures from Temples and Palaces, vol.II,

Asian Art Gallery, London 2005, p.97-109.

89 See M.Henss, Liberation

from the Pain of Evil Destinies. The Silken Images (gos sku) of Gyantse

Monastery. Proceedings of the Tenth IATS Seminar, Oxford 2003, edited

by E.Lo Bue, Leiden 2007, and for the methods and techniques of Tibetan

painting in general D.P. and J.A.Jackson, Tibetan Thangka Painting. Methods

and Materials. London 1984.

|