asianart.com

HOME | TABLE OF CONTENTS | INTRODUCTION

Download the PDF version of this article

by Elisabeth Haderer

(Numata Center for Buddhist Studies, Asia Africa Institute, University of Hamburg/Germany)

Published May 2020

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

Introduction

Since the occupation of Tibet by Chinese Communist Government in 1959 and the resulting diaspora of the Tibetans, Tibetan Buddhism and its art have been constantly finding their way into Western countries and societies.

Today, Tibetan Buddhism is at a historic turning point. Just as Buddhism once came from India to Tibet about 1300 years ago, its teachings, meditation practices and art are now becoming part of a new cultural environment. This process involves modification and renewal.

Most of the spiritual leaders of the various Tibetan Buddhist traditions live in exile in India today. In order to preserve Tibetan Buddhism, many Buddhist centers and institutions have been established under their spiritual guidance all over the world, in particular in Europe, in the United States and in Russia. In accordance with Tibetan Buddhist tradition, these places were decorated with ‘authentic’ Buddhist art, painted scrolls (Tib. thang ka), wall paintings (Tib. logs bris) and sculptures (Tib. sku ‘dra).

The Transmission of the Karma Gardri Tradition to the West

One of the first Tibetan Buddhist artists who came to Europe in the 70ies of the 20th century was the well-known Tibetan Buddhist artist Gega Lama (1931-1996). He was one of the last master artists of the Karma Gardri [1] (Tib. karma sgar bris) tradition, the “the painting style (bris) of the Karmapa (karma) tent camp (sgar)”. As the term suggests, this style was developed in the famous tent camp of the Karmapas, who have been the spiritual leaders of the Tibetan Buddhist Karma Kagyü tradition since the 12th century. Beginning in the 15th century the Karmapas would travel through Tibet accompanied by hundreds of their followers, who all lived in tents. Among the students were also very gifted artists, who experimented with new styles of art. One of them was Namka Tashi, who in agreement with his teacher, the eighth Karmapa Mikyö Dorje (1507-1554), invented the Karma Gardri style in the middle of the 16th century. In general, the Karma Gardri style is famous for its spacious landscapes, brilliant colors, sparse use of gold color as well as the naturalistic and precise depiction of figures, portraits and landscape elements.

Gega Lama was sent by the 16th Karmapa, Rangjung Rigpe Dorje (1924-1981), in order to teach Buddhist art and painting to the people in the West[2]. One of his first Western female students was German artist Bruni Feist-Kramer (born in 1935). A mother of four children, she studied graphics at the Academy of Arts in Düsseldorf, where she graduated in 1976[3].

In her book on Tibetan thangka painting, Feist-Kramer mentions that she had rather negative emotions when she saw a Tibetan painting for the first time. Thangkas appeared to her as naïve paintings that depended on strict rules and rigid regulations. She also had the impression that one Tibetan painter just copied another. One day she came across a program in which a thangka painting course was announced. There she read a short description of how a Buddha figure is represented in Tibetan art. To her surprise she found it very interesting and was curious to learn more about it. So she registered at the course guided by Gega Lama. As a result she got totally inspired by drawing a “correct and good” Buddha figure. “Correct” means that the figure corresponds to the given iconometric measurements, and “good” means that the figure leaves a lively impression[4].

According to Tibetan Buddhism, the main purpose of the different Buddhist deities is to dissolve suffering and hindrances, such as the imbalance of the five elements, diseases or a short life. In a wider sense, they are supposed to help awaken the so-called buddha nature or potential to become a Buddha, an “awakened one”, which is thought to be inherent in every living being, even in the tiniest insect. This is achieved by practicing meditation on the Buddhist deities, or even by looking at a “good and correct” representation of them on a thangka or as a sculpture[5].

Gega Lama gave his students five basic instructions on authentic Buddhist art. First, a Buddhist artist should base his or her work on the Buddhist scriptures on art. Second, he or she should study the appearance of the Buddhist deities and the symbolism that is connected with them, such as their color and looks, the jewels and the dresses they wear, the hand gestures (Skt. mūdra; Tib. phyag rgya) that they perform, their sitting postures, etc. Third, the artist should not only know all these things but also practice meditation. Fourth, the artist should know to which category the Buddha form he paints belongs: for example, whether it is a Buddha or a Bodhisattva, a meditation deity (Skt. iṣṭadevatā; Tib. yi dam) or a fierce dharma protector (Skt. dharmapāla; Tib. chos skyong), a human or a celestial being such as a god, etc. There are different instructions for the artist, depending on the level of the spiritual realization of these beings. Thus, for example, if they belong to the so-called lower tantra classes, the artist is supposed to keep the surroundings and his painting materials clean, avoid eating meat and drinking alcohol etc., while if he paints a deity belonging to the higher tantra classes, he should also meditate on these forms and say their mantras or root syllables during the act of painting. And fifth, the paint should be made of or enriched with earth, plants and stones, i.e., with natural ingredients. Furthermore, it is said that it makes a difference if the painting utensils get blessed by an authorized Buddhist teacher or a lama[6].

Tibetan Buddhist Art Goes West

The start of Bruni Feist-Kramer’s career as one of the first Western thangka painters of the Karma Gardri style is a good example for the so-called ‘transmission’ of authentic Tibetan Buddhist art. That is, to become the student of an authorized art teacher and follow his/her guidance until one becomes a master oneself.

In connection with the transmission of traditional Tibetan Buddhist art to the modern Western world, some crucial questions arise:

1) What does the term ‘transmission’ imply?

In Tibetan Buddhism the close connection between teacher and student plays a crucial role. Ideally, the teacher is seen as a ‘living’ Buddha, as someone who has already – or at least almost – reached the goal of enlightenment. It is also believed that the authentic teachings of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni have been transmitted from master to student by an unbroken lineage of spiritually enlightened masters up until today. In this context, ‘transmitted’ means, not only in an oral way or on the basis of texts, but, most importantly, by the experience from what is taught[7].

In a similar way, Tibetan Buddhist art has been passed on from one generation of artists to another. Traditionally, the techniques and knowledge of producing Buddhist art were solely transmitted among the male members of a family. Before 1959 an authentic traditional Tibetan Buddhist artist had to be born in Tibet, had to come from an old, renowned family of artists, and had to be formally educated as traditional Buddhist artist. Since then these quite restricted standards have been loosened a bit, because of the new situation of the Tibetans living in exile[8].

Fig. 1

The Tibetan Dawa Lhadripa is a contemporary master artist of the Karma Gardri tradition (fig. 1). He was born in Yolmo/ Nepal in 1961 and he started to study traditional Buddhist art at the age of thirteen. Because there were no official art schools, he learned the art of painting from private teachers. One of them was the above-mentioned Gega Lama, with whom he studied for one and a half years. In an interview Dawa Lhadripa mentions that the complete training of a Tibetan Buddhist artist lasted thirteen years in former times and, if that was not possible for some reason, nine years at least. Nowadays, it takes two to five years because “everything has to be fast”, as he puts it. Concerning his training as an artist, there was no fixed program and he did not have exams or a final test as in school. He always had the sense of learning and working at making his techniques perfect at the same time. Thus, it is hard to tell when the training is complete. “Maybe if your teacher tells you to paint the inside of a monastery”, he concludes laughing. The way of learning is working together, but this does not mean that the students are not tested. On the contrary, they get checked by the teacher all the time, especially when they have to present their work to him. Dawa Lhadripa finished his education as an artist at the age of 22, but he still had the feeling that he was not ready. So he went to his teacher and asked him for further teachings. When Gega Lama saw his work, he told Dawa that he cannot teach him anything more and that he would even paint better than himself. He said: “You are an excellent artist. Now develop your abilities and continue working for the dharma and for the benefit of all beings. Thank you for your coming”. Following the advice of his teacher, Dawa Lhadripa started to work by himself and to paint without the supervision of his teacher. Since that time he has worked in 27 Buddhist monasteries and institutions in Nepal, India, Singapore, Malaysia and the USA. In 2002 he came to Europe for the first time to carry out the wall paintings in the meditation hall at the Karma Kagyü retreat center in Vélez-Málaga in Spain. Currently the artist also has plans to found an art school in Europe, in order to preserve and transmit the Karma Gardri painting style[9].

2) How does the process of adaptation of traditional Tibetan Buddhist art take place?

Traditionally, Tibetan Buddhist artists consult oral, artistic and written sources for their work.

Oral transmission

Fig. 2

German sculptress Petra Förster (born in 1964) produces traditional Tibetan Buddhist sculptures made of clay. In 2007, the artist and her team of international colleagues founded the Buddhist Institute of Tibetan Art (BINTA) in Braunschweig, Germany. The main goal of this voluntary institution is to receive the transmission of traditional Tibetan Buddhist art and to maintain it. Searching for an authentic art teacher, Petra Förster went to Ladakh in Northern India in 2009. In Leh she met the famous Buddhist sculptors Ngawang Tsering and his son Chhemet Rigdzin (born in 1972). Father and son have specialized in the century-old technique of producing clay statues that came to Tibet from China via the Silk Roads around the 7th century C.E. Because Chhemet Rigdzin speaks English, Petra Förster invited him to Germany, in order to build a Buddha sculpture together with her and her team of artists. In 2010 the master came to Braunschweig for the first time. At an “auspicious day”, according to the Tibetan calendar, they started with the construction of the sculpture of the Buddhist deity Cakrasaṃvara (Tib. 'khor lo bde mchog) and his female partner Vajravārāhī (Tib. rdo rje phag mo) in sexual union[10]. (fig. 2)

In her article “Buddhas aus Ton”, Förster mentions that, despite traditional conventions concerning the measurements and the appearance of a Buddha figure, an experienced artist is able to make modifications during the process of producing of a sculpture. In the beginning, the student follows the example of the teacher. After the student has achieved certain skills, he/she can also make alterations. Thus, for example, her teacher Chhemet Rigdzin developed a special mechanism for the Buddha sculpture (fig. 2) mentioned above. This innovation allowed it to be filled with blessed items and relics after its completion and not already during the process of production, as it is normally the case. He inserted a screw in the knee of the female deity’s bent leg so that it could be flipped back. In this way free access was granted to the back of her male partner from where the statue traditionally gets filled[11].

Moreover, the statue was not painted when finished, but was left ‘naked’. Just the eyes of the figures were ‘opened’. In Tibetan Buddhist art, the painting of the eyes is the last step within the production process of a thangka or sculpture. By painting the eyes, the Buddha figure is thought to come alive. It is believed that, if it were done before its completion, bad energies would take possession of the unfinished body[12]. Whereas in Ladakh the statues are painted in bright colors and get varnished with lacquer for protection afterwards[13]. I suppose it might be a concession to the more puritan Western aesthetic taste that the sculpture is left unpainted.

Visual models

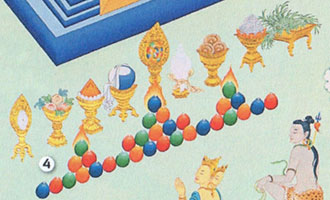

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Besides the oral instructions of the teacher, famous Buddhist works of art are the second important visual guideline for an artist. These, for example, can be portraits of Buddhist teachers that were made when they were still alive and confirmed by them as a good likeness (Tib. nga 'dra ma) or even self-portraits (Tib. nga 'dra ma phyag mdzad) that they made themselves[14] such as a famous sculpture of the eighth Karmapa Mikyö Dorje (1507-1554) who was a great artist. According to legend, it was made by him and after it was finished he is reported to have asked it: “And, are you a good likeness of me?” Thereupon, the statue should have answered: “Yes, indeed, I am”[15]. Such works of art are believed to carry a special blessing and are regarded as worth being copied by artists of all times.

Today, it is also common to use a photograph of a Buddhist teacher as a template for his portrait. Dawa Lhadripa, for example, used a picture of the 16th Karmapa for his photorealistic portrait in the wall paintings of the Buddhist retreat center ‘Karma Guen’ in Spain[16]. (fig. 3) Petra Förster did the same for her clay statue of the 16th Karmapa[17]. (fig. 4)

Textual sources

In addition to oral instructions and visual guidelines, Tibetan Buddhist artists also consult written sources for their work, such as texts on iconography, iconometry or the symbolism of Buddha figures. Chhemet Rigdzin and Petra Förster, for instance, use the manual “The new book on the painting system of Tibet: The sun which benefits everybody” (Tib. bod kyi ri mo 'bri tshul deb gsar kun phan nyi ma[18])[19].

For the portraiture of Buddhist teachers, their hagiographies or spiritual biographies (Tib. rnam thar) are often taken into account.[20]. These usually contain many details on their lives such as their birth, parents, education, travels, teachers and students, meditation practices and spiritual experiences, the miracles they are supposed to have worked or that occurred in their presence, the circumstances of their death, etc. In rare instances, these life stories also give information on what the masters looked like and what character they had.

Another important written source for the representation of a Buddhist figure or teacher is the meditation instructions (Skt. sādhana; Tib. sgrub thabs). These often give a quite detailed description on their appearance, the attributes they hold in their hands, the clothes they wear, the hand gestures they perform, the sitting position etc. as well as the symbolism of the individual features[21].

3) Does an independent ‘Western Buddhist art’ or ‘style’ already exist?

Fig. 5German thangka painter Bruni Feist-Kramer states that thangka painting is not about imitating foreign cultures. Modifications in Tibetan Buddhist art will happen naturally when Buddhism permeates Western culture and when people are able to leave behind their narrow habitual way of thinking. In her opinion, new forms of expression can arise out of a realized view[22].

Can one already speak of an independent Western or European Buddhist art? Are there, for instance, any distinctive stylistic features by which one can see if a thangka or Buddha sculpture was created by a Tibetan or a Western artist?

In order to present some answers to these questions, I will now compare the painting of a Tibetan artist with that of a Western one.

Both works of art show the ‘Deeds of the Buddha’, which is a classical theme in Tibetan Buddhist art.

The ‘Deeds of the Buddha’ by Dawa Lhadripa

The first example are the wall paintings by contemporary Tibetan Karma Gardri master artist Dawa Lhadripa (fig. 1) that he painted in the meditation hall of the Karma Kagyü retreat center named ‘Karma Guen’ in Vélez-Málaga/Spain from about 2004 to 2006.

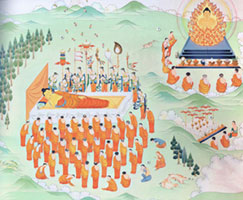

In the wall paintings in Karma Guen, Dawa Lhadripa painted eighteen main scenes on five walls in total. On the fifth wall the following scenes are depicted: ‘Turning of the Dharma Wheel’, ‘Parinirvāṇa’, ‘Cremation’ and ‘Distribution of his Relics’. (fig. 5)

The Scene of ‘Turning of the Dharma Wheel’ (Teaching)

Fig. 6 |

Fig. 6a |

Fig. 6b |

Fig. 6c |

Fig. 6d |

Fig. 6e |

Stylistic analysis

Characteristic of the Karma Gardri style is the vast and spacious landscape with scattered hills, rocks, trees, flowers, clouds and animals. The colors are especially bright, and the shading is so refined that the colors merge nearly unnoticeably from dark to light. In particular, the transparent parts, such as the halos and clouds, were painted in a masterful manner. The elegant figures show individual faces, wear different clothes and perform naturalistic gestures and movements. The outlines are fluent and the clothes form natural folds, which accentuate the bodies of the figures.

For that scene, the artist chose a totally new way of representation. The Buddha is depicted in a three-quarter view and from above, whereas the minor figures are arranged around him in a semi-circular way. In addition, the various groups of figures and even the single figures are shown from different angles, some from the side and some from behind. Furthermore, the minor figures are represented at a much smaller scale than the Buddha. All these details create an exceptionally high degree of spaciousness.

When looking at the painting, one even gets the impression as if flying over the scene. The employment of different perspectives completely dissolves the two-dimensionality that is prevalent in traditional Tibetan Buddhist painting. As a result, the wall paintings appear modern and in accordance with tradition at the same time.

The ‘Deeds of the Buddha’ by Bruni Feist-Kramer

The seven panels on cloth were painted from 1999 to 2001. (fig. 7) All the scenes were designed and drawn by the artist herself except for two scenes painted by Dutch thangka painter Marian van der Horst-Lem. During the process of painting, Feist-Kramer was also assisted by her as well as three other Russian painters[23].

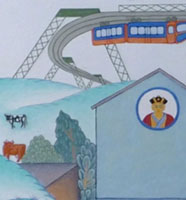

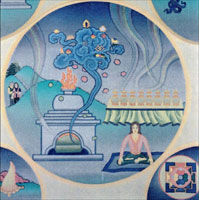

Fig. 7One of the first things that one notices when taking a look at the paintings of the ‘Deeds of the Buddha’ by Feist-Kramer is the layout, which is quite untypical of traditional Tibetan Buddhist painting. All thirteen scenes are arranged on seven separate canvases of vertical format. On each plate two scenes are painted, except for the central plate that is a painting of its own. Moreover, the main scenes are contained in circles in the upper and lower part of the paintings, while the minor scenes are depicted within semi- and quarter-circles at the borders and corners of the paintings. These minor scenes show the traditional set of the eight stūpas (Tib. mchod rten) housing the relics of the Buddha, which refer to certain events and deeds in his life. Further, the small circles show different sets of auspicious symbols. On some plates several additional scenes were added.

The Scene of the ‘Turning the Dharma Wheel’ (Teaching)

On the central plate (fig. 8), the Buddha (fig. 8a) sits on a throne with an octagonal base with supporting lion figures as well as on a lotus flower and a moon disc. He wears the threefold robes decorated with beautiful and delicate golden ornaments, and he performs the gesture of turning the dharma wheel. In the sky, on his left and right side, a male daka (Skt. ḍāka; Tib. dpa' bo) and a female dakini (Skt. ḍākinī; Tib. mkha' 'gro ma)[24] are floating on clouds. As a sign of veneration, they present a golden dharma wheel and a white conch to the Buddha.

Fig. 8 |

Fig. 8a |

Fig. 8b |

Fig. 8c |

On the right side stands a Tibetan monk (fig. 8c) who holds his left hand to his ear as he listens to the Buddha’s teachings. Behind stands a Western couple. (fig. 8c) The woman has long blond hair and wears a blue dress. Her partner is standing directly behind her and embraces her by putting his hands around her hips. He has short brown hair and wears an ‘Asian’ style vest with a wide collar and a belt. Both of them are looking at the Buddha. The woman offers a bowl of yoghurt to him. “The yoghurt is a symbol for the development of mind through the process of hearing, contemplating and meditating,” the artist writes. Further in the background a young noble man and his horse are paying homage to the Buddha. (fig. 8c) It is the young king of Magadha, who became a friend of the Buddha after his enlightenment. According to Feist-Kramer, he is representing all those who carry a lot of responsibility and can benefit many.

Fig. 8d |

Fig. 8e |

Fig. 8f |

Stylistic analysis

“In the pictures I merged historical facts, legends and my own visual ideas about the events”, says Bruni Feist-Kramer about her painting of the ‘Deeds of the Buddha’[25].

What is traditional and what is new about Feist-Kramer’s interpretation of the Buddha’s life and deeds?

As with Dawa Lhadripa’s painting, Feist-Kramer’s work also shows the distinctive stylistic features of the Karma Gardri style. The landscape is spacious, but more in a sense that it extends into the background. This might be due to the limited horizontal space within the circles. The green and blue shades of the landscape and the sky are graded and change from darker into brighter hues. Yet the paint application appears to be stronger and the colors more intense than in Dawa Lhadripa’s wall paintings. The figures in Feist-Kramer’s paintings are rendered in a stylized or even simplified manner. Nevertheless, they show natural gestures and movements, which convey a very lively impression. What is completely new is that Feist-Kramer puts a noticeable emphasis on the representation of Western Buddhist laypeople and mainly on women who get in contact with the Buddha.

Comparison

Fig. 9

What are the differences between Feist-Kramer’s (figs. 7, 8) and Dawa Lhadripa’s (figs. 5, 6) painting style?

Concerning the representation of the scenes, the Tibetan artist clearly followed a more traditional way of illustrating the specific subjects and motifs. But he also interpreted some scenes – such as the Buddha’s cremation (fig. 5) – in a rather uncommon and inventive way. In that scene, he illustrated just the upper body of the Buddha, surrounded by flames, which does not get burnt by the fire.However, Feist-Kramer chose a quite different approach. She used a very uncommon – vertical – format for her seven paintings. So far, the integration of the scenes within circles, semi- and quarter circles has been absolutely unique.

In terms of style, Dawa Lhadripa’s way of painting exhibits a flawless application of color, an exceptional high degree of spaciousness, and a natural liveliness of the figures.

In comparison, Feist-Kramer’s style conveys a more grounded or ‘down-to-earth’ impression. The colors appear to be more intense and the shading stronger. The details, such as the cloth patterns or plants, are very elaborate, whereas the figures’ bodies and faces are painted in a more abstract and stylized manner. Nevertheless, the minor figures’ exceptional postures, movements, garments and looks confer a very contemporary touch to the paintings.

Fig. 9a In summary, the perfect painting technique and the more traditional interpretation of the scenes indicate that the wall paintings showing the ‘Deeds of the Buddha’ (fig. 6) were created by a Tibetan painter. Furthermore, the especially bright colors, the composition’s enhanced three-dimensionality, and the minor figure’s expressive gestures suggest that the paintings were created by a contemporary Karma Gardri artist.

On the other hand, the uncommon format and layout of the paintings, the non-traditional interpretation of some scenes and the presence of many Western people at central positions indicate that the ‘Deeds of the Buddha’ (fig. 7) was created by a Western artist or artists. Moreover, the symbolic references to a German city and area in the background suggest a German painter or sponsor of the painting. The many female figures portrayed as students of the Buddha and practicing meditation indicate that the artist is female. Finally, the artist’s small self-portrait in the scene of the Buddha’s cremation (fig. 9, 9a), which shows Bruni together with her husband, is an unmistakable proof that the painting is a work by Bruni Feist-Kramer.

4) Which role do female artists play in contemporary Tibetan Buddhist art?

In his article “Thangkas and Tourism in Dharamsala: Preservation through Change” (1996), the author Eric McGuckin states that none of the Tibetans he spoke with in Dharamsala was “aware of any female painters in traditional Tibet”. However, Tibetan women in exile have begun producing thangkas, though their numbers remain small. Among the estimated 200 traditional thangka painters in Dharamsala in the mid-1990s allegedly only three painters were female. A Tibetan thangka painter indicated that, although there are no restrictions for female painters in the Buddhist texts, he has never had a female student. “According to Tibetan tradition, women don’t do certain things like thangka painting. People think that if a woman does, it will be an awkward thing, even if the Buddha never said one word against it,” the man explained. Despite these continuing gender attitudes, the urgency of preservation of the Tibetan culture loosens customary restrictions. A monk painter comments that “according to Buddhist teachings, women can’t do thangka painting. But according to our situation, the need for preservation, anybody can do it; even people without a philosophical background, even women and laymen”[26].

In contrast, most of the contemporary Tibetan Buddhist artists in Europe are women. This may be due to the fact that Tibetan Buddhism in Europe is mainly maintained and practiced by laypeople, men and women alike, who are “more or less looking for ways to integrate Buddhist teachings and practices into their secular, everyday life”, as Inken Prohl comments[27]. It seems that the interest in traditional Tibetan Buddhist art and its production is more of a female task in the West. However, Bruni Feist-Kramer mentions that Gega Lama’s wife, Rinchen, showed her and the other students the best shading techniques when painting together for one summer season.[28]

Conclusions

The process of transmission involves three different approaches or sources. First, oral instructions based on close cooperation or even friendship between teacher and student; second, written sources, such as texts on iconography and iconometry, spiritual biographies and meditation instructions; and third, visual models, such as famous works of Tibetan and Indian Buddhist art history.

As comparison of two contemporary paintings by a Tibetan and a Western Buddhist artist has shown, an independent ‘Western’ Karma Gardri painting style has not emerged so far. Nevertheless, one can distinguish a painting by a Tibetan Buddhist artist from that of a Western painter in terms of the topic’s interpretation, the compositional layout, the figural representation and the painting style.

Whereas in Tibet the production of traditional Buddhist art was an exclusively male task, the situation has changed with the diaspora of the Tibetans around the world. While there are still only a few female Tibetan Buddhist artists, the majority of western Buddhist artists are women. This may stem from the fact that in Europe significantly more women than men start studying and producing traditional Tibetan sacred art.

In an interview, contemporary Karma Gardri artist Denzong Norbu (born in 1935) was asked how he sees the future of Buddhist art. Denzong Norbu answered: “In the future I wish that we produce statues in Europe. The quality of art works from Nepal and India has strongly decreased in the past years […] In the past, thangka painters had a good reputation. Just a few held the transmission and knew the special techniques. But nowadays, due to commercialization of the market, anybody can produce statues and thangkas. It is a pity. Let us try to get back to quality instead of quantity”.

Asked which vision he has for Tibetan Buddhist art in Europe, he replied, “[…] Europe has a good future, Asia is lost. Everything gets mixed up there; there is nothing authentic, rare or special anymore. But in Europe we have many possibilities. […] What makes the difference? In Asia artists just work for money, but in Europe people work for the dharma. […] Buddhism will grow here. Since the time I came to Europe for the first time until now, there is a huge difference, an enormous growth. I really hope that more and more people will come. This is the power of Buddhism that is not for retreat and books, but to show that it works and actually has some effect”[29].

Footnotes

1. See David Jackson, A History of Tibetan Thangka Painting: The Great Tibetan Painters and Their Traditions (Wien: Verlag der Akademie der Wissenschaften 1996), 169-173, 260-283.

2. See Bruni Feist-Kramer and Anna Lieb-Dubino (eds.), Reine Formen: Einblicke in die Welt der Thangka-Malerei, Noderstedt: BoD – Books on Demand, 2016.

3. See Bruni Feist-Kramer, written correspondance, 2005.

4. See Feist-Kramer, Reine Formen, 10, 27.

5. See Feist-Kramer, Script on thangka painting, unpublished, no place, no year, 2.

6. See Feist-Kramer, Reine Formen, 11, 12.

7. See Andrew Quintman, “Bka’ brgyud (Kagyu)”, in The Encyclopedia of Buddhism, ed. Robert E. Buswell, Jr. et al. (New York et al.: Mcmillan Reference, 2004), 47-49.

8. See Clare Harris, In the Image of Tibet: Tibetan Painting after 1959 (London: Reaktion Books, 1999), 55.

9. See Agnieszka Nowinska and Eduardo Bombarelli, “‘Ich bin immer von Buddhas umgeben’: Interview mit Dawa Lhadripa,” Buddhismus Heute 41 (2006): 62-67, http://www.buddhismus-heute.de/archive.issue__41.position__11.de.html, accessed April 18, 2017.

10. See Petra Förster, “Buddhas in Ton,“ Buddhismus Heute 51 (2012): 73, 75.

11. See Förster, “Buddhas in Ton,“ 75.

12. See Feist-Kramer, Script on thangka painting, 27.

13. See Förster, “Buddhas in Ton,“ 74.

14. See Heather Stoddard, “Fourteen Centuries of Tibetan Portraiture,” in Portraits of the Masters: Bronze Sculptures of the Tibetan Buddhist Lineages, ed. Donald Dinwiddie (Chicago: Serindia Publications, 2003), 32.

15. See Nik Douglas and Meryl White, Karmapa, the Black Hat Lama of Tibet (London: Lucazs, 1976), 138.

16. See Elisabeth Haderer, Die Entwicklung der Karmapa-Darstellung der Karma Kagyü-Schule des Tibetischen Buddhismus: Thangkas, Wandmalereien und Bronzen der tibetischen Kunsttradition vom 13. bis zum 21. Jahrhundert, Zwei Bände, Universität Wien, 2007, 109, 110, http://othes.univie.ac.at/267/.

17. Petra Förster, personal communication, Braunschweig, January 2015.

18. Jamyang Losal. The new Sun self-learning Book on the Art of Tibetan Painting (Tib. bod kyi ri mo 'bri tshul). Dharamsala, 1982.

19. Petra Förster, personal communication, Braunschweig, October 2014.

20. Bruni Feist-Kramer, personal communication, Mettmann, 2005.

21. See for example, 16. Karmapa Meditation, ed. Buddhismus Stiftung Diamantweg (Darmstadt, 2010).

22. See Feist-Kramer, Script on thangka painting, 35.

23. Bruni Feist-Kramer, written commentary.

24. In traditional Tibetan Buddhist paintings the Hindu gods Brahmā and Indra are usually depicted. (see, for exmaple, Hans Wolfgang Schumann, Buddhistische Bilderwelt: Ein ikonografisches Handbuch des Mahāyāna- und Tantrayāna-Buddhismus (Köln: Eugen Diederichs Verlag, 1986), 58).

25. Bruni Feist-Kramer, written commentary.

26. See Eric McGuckin, “Thangkas and Tourism in Dharamsala: Preservation through Change,” The Tibet Journal, ed. Massimiliano A. Polichetti, et al. 21/2 (1996): 39, 40.

27. Inken Prohl, “Buddhism in Contemporary Europe,” in: The Wiley Blackwell Companion to East and Inner Asian Buddhism, ed. Mario Poceski (Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. Ltd., 2014), 486.

28. See Feist-Kramer, Script on thangka painting, Preface.

29. Astrid Schmidhuber, “‘In Zukunft wollen wir Statuen in Europa herstellen:‘ Interview mit dem Tangka-Maler Norbu,“ Buddhismus Heute 40 (2005): 78, 79, http://www.buddhismus-heute.de/archive.issue__40.position__11.de.html, accessed April 25, 2017.

HOME | TABLE OF CONTENTS | INTRODUCTION

asianart.com