Nagas in Indian art and mythology

According to the

epics, a tribe called the Nagas was spread throughout India during the

period of the Mahabharata. It seems likely that the Naga people were a

serpent-worshipping group who were later described as serpents themselves

in ancient Indian literature.

The great importance

of the Nagas in Buddhist and Hindu religion is reflected in plastic and

pictorial art, as well as in extensive descriptions in the old Hindu texts,

which report dynasties of Naga kingdoms of which Nagaland is the last

relic. The Naga (skt. naga – snake) of Indian and Buddhist

mythology is usually not the snake in general but the cobra, raised to

the rank of a divine being.

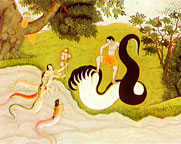

Images, sculptures

and the narratives of literature present the serpent in two forms:

• Theriomorphic,

i.e. in his animal shape, usually many-headed and represented erect, spreading

its hood (fig. 1, below)

• Anthropomorphic as serpent god (Nagaraja), canopied by one or

several hoods (fig. 2, below)

• Therioanthropomorphic form with a human head and torso and a serpent

tail (fig. 3, below)

Fig. 1: Theriomorphic form of a

polycephalic cobra |

Fig. 2: Anthropomorphic

form as serpent god |

Fig. 3: Therioanthropomorphic

form with a human head |

Nagas in Hindu mythology

are the sons of Kadru, the personification of the Earth. Many of them

are known by their individual names and have a history of their own. The

longest list of Naga names – well over 500 – is given in the

Nilamata Purana of Kashmir which dates back to the eighth century.

Fig 4: Vishnu sleeping on the endless

serpent Shesha

|

|

In the list of the

divine serpents of the epic literature Shesha (or Ananta) usually figures

first. He is the Endless, the cosmic serpent on which Vishnu sleeps, (fig.

4, left) as he dreams the universe into existence. Shesha embodies the

primordial substance of which the universe is formed, which remains when

the universe ends and initiates the start of the next cosmic cycle. Shesha

is also the king of all Nagas who holds the planets on his hoods and constantly

sings the glories of Vishnu from all his mouths. Vishnu resting on Shesha

is a favorite theme of plastic art. He is shown reclining on the couch

formed by the coils of the Naga whose polycephalic head with wide spread

hoods forms a canopy over the god. One of the most famous depictions is

a seventh century sculpture in the cave temples of Mahabalipuram. (fig.

5, below)

Vasuki, another prominent

king of the Nagas, usually figures second and immediately after Shesha.

The most famous legend in Hinduism narrates how Vasuki allowed the gods

to use him as a rope, bound with Mount Meru, when gods and demons together

churned the ocean of milk for the ambrosia of immortality. Vasuki is mainly

associated with Shiva; he is represented slung around his neck and often

venerated in form of a brass image.

|

Fig 5: Vishnu in his cosmic sleep |

Muchilinda, another

mighty king of serpents, during a heavy rain came from his abode beneath

the earth to protect the meditating Buddha by coiling around his body

and spreading his hood over his head. When the storm had cleared, the

serpent king assumed his human form, paid reverence to the Buddha and

returned in joy to his palace.

Karkotaka is said

to control the weather. In mythology he was a Naga king, who bit the sage

Nala at the request of Indra, transforming him into a misshapen dwarf

with short arms.

Paravataksha is a

Naga whose sword causes earthquakes and whose roar brings thunder.

Manasa Devi, a serpent goddess, is Vasuki's sister. She can cure any snakebite

and indeed any adversity. She is widely worshipped in Bengal.

Ulupi, a Naga princess

in the epic Mahabharata, abducted the prince Arjuna to her realm in the

netherworld and had with him a son Iravat, who later assisted his father

in the battle of Kurukshetra. |