asianart.com | articles

Catalogue

Download the PDF version of this article

by Karl Debreczeny

Published May 30, 2019

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

(Note that not all figures referenced in the text are shown in this article: those that are shown are listed in bold;

others, not in bold, are not shown in this article - but can be found in the catalogue (see link above))

Religion’s role in politics has been a universal theme across times and cultures, evident from

the earliest archaeological records to the present day. This intersection of religion and politics is critical in

understanding the spread and impact of Tibetan art across Asia from the ninth to the twentieth century.

At the heart of this dynamic is the force of religion to claim political power, both symbolically as a path to

legitimation, in the form of sacral kingship, and literally as a tantric ritual technology to physical power,

in the form of magic. To these perennial elements of religion’s role in the political realm, Tibet contributed

reincarnation as a means of succession, first in its own courts and then in empires to the east. Images were a

means of political authority, serving as embodiments of power.

Still, Buddhist involvement in politics is largely invisible in the popular view of the Dharma. This

gap stems from Western perceptions of the tradition, which are mostly romanticized projections born from

colonial encounters. In fact, Buddhism has been engaged as a political force since its early days, beginning

in India (see chapter 2). In Tibet, religious and political authority became so intertwined as to be inseparable, and they were acknowledged as such. The notion that Buddhism is historically a religion of nonviolence is also a common misconception.[1] To project this idea into the past is both ahistorical and misleading.

The objective of the book Faith and Empire: Art and Politics in Tibetan Buddhism and the exhibition of the

same name is to reground Tibetan Buddhist art in its historical and global context and highlight a dynamic

aspect of the tradition related to power, one that may run counter to popular perceptions, yet one that is

critical to understanding this tradition’s importance on the world stage.

Religion and politics have long enjoyed a symbiotic relationship. Sacred art has served as both an active agent and primary medium of government propaganda. State sponsorship has allowed religious traditions to flourish and spread, resulting in the creation of many masterpieces. Court patronage played a central role in the support and spread of Buddhism throughout Asia. With the spread came the transmission of a complex visual culture that continued to develop as it adjusted to each cultural context, such as rule of China by the Mongol and Manchu empires. This provided fertile territory for the emergence of hybrid traditions, as the needs of patrons were turned into visual forms by local artists using imported models, with the works created taking on their own political signifcance.

Buddhism was especially attractive to conquest dynasties because it offered a model of universal sacral kingship that transcended ethnic and clan divisions and united disparate peoples. It also promised esoteric access to physical power that could be harnessed to expand empires. By the twelfth century, Tibetan

Buddhist masters had become renowned across northern Asia as bestowers of this anointed rule and occult power. Prominent rulers such as Qubilai Khan (1215–1294) embraced this Buddhist path, and it is this political role that transported Tibetan Buddhism beyond its borders. In politics, this faith was a path to legitimation and a means to power; its rituals were potential weapons of war and its art a conduit.

TIBETAN EMPIRE

Fig. 1.1

From the seventh to the ninth century, Tibetans dramatically stepped onto the world stage for the first time

in the form of the Tibetan Empire (ca. 608–866), one of the great military powers of Asia and the greatest

military rival of China’s Tang dynasty (618–907). As we learn in chapter 2, both the concept of sacral kingship and the martial cult of wrathful deities were elements of Tantric Buddhism introduced from India;

politics had always been at the center of what became known as Tibetan Buddhism.[2] The Tibetan court had a cosmopolitan vision embracing many surrounding traditions, including a writing system inspired by

Sanskrit, Buddhism introduced by monks from Khotan in Central Asia and scholars from India, Sasanian

silver-working techniques by way of the Sogdians (see fig. 3.5), Greek medicine via Persia, and record keeping drawn from Tang China.[3] Part of this internationalism resulted from Tibetan rule over portions of the Silk Road, an important economic artery where political symbolism manifested in religious art. As we will see in chapter 3, it is in this period that the Tibetan emperors became divine rulers (see figs. 2.6 and 3.2), regarded as emanations of the Buddhist deity, bodhisattva, and patron deity of Tibet, Avalokiteśvara (see fig. 3.1). This conflated identity became an important political symbol, especially with the later reunifcation

of Tibet under the Dalai Lamas (see chapter 7), embedded in Tibetan national identity even to this day.

Fig. 3.5Some of the earliest surviving evidence of visual expressions of Tibetan political power in religious art

dates to this period in the eighth century when the Tibetan Empire ruled over large Chinese populations

in the Hexi area of Gansu, including Dunhuang, an important center of Buddhist cave temples and translation activity located in the Gobi Desert near the eastern end of the Silk Road. During the period of the

Tibetan rule of Dunhuang (781–848), Tibetans patronized local workshops while introducing new visual

forms into the local established traditions (see figs. 1.3 and 3.6). In 781, Tibetan Buddhism and art were still

in their formative stages, as the first Tibetan monastery, Samyé, had been founded only two years earlier in 779, coinciding with the adoption of Buddhism as Tibet’s state religion. Thus, the scriptural translation and

artistic activity at Dunhuang also had a significant impact on what was to become Tibetan Buddhism.

Fig. 3.6This period saw the appearance of Tibetan rulers in Chinese paintings that make political statements,

such as an illustration from Dunhuang’s Cave 158 (fig. 1.1), one of the so-called nirvāṇa caves, in which the

Tibetan emperor leads the monarchs of the Buddhist world in grieving for the passing of the Buddha.[4] While

this painting was vandalized in the 1970s during the Cultural Revolution, a photograph by the French scholar

Paul Pelliot from the early twentieth century reveals this figure was labeled tsenpo, the Tibetan imperial dynastic title reserved for the emperor. An illustration from the Vimalakīrti-nirdeśa-sūtra from Cave 231 (fig. 1.2), a

cave sponsored by the local Chinese Yin 陰 family and dated 839, depicts a lofty spiritual debate between the

Bodhisattva of Wisdom, Mañjuśrī, and the famous lay-scholar Vimalakīrti. Yet the painting also lays bare the

political relationship between the Tang and Tibetan empires: the Chinese emperor has lost his sword and is

down to a single tassel of rank on his cap, while the Tibetan emperor is noticeably larger and raised on a dais,

and his camp is armed to the teeth.[5] The painting dates to shortly after this region—the Hexi Corridor—was

ceded by the Tang to the Tibetan Empire in 822; this religious painting, commissioned by one of the leading

local Chinese families at Dunhuang, makes a clear, dramatic statement about the political realities of the day.[6]

Not all paintings at Dunhuang under Tibetan rule were simply continuations of the same Chinese

workshops from the High Tang. Tibetan religious and aesthetic interests began to assert themselves, and

new visual models appeared alongside, or even combined with, Chinese ones (see fig. 3.6). These new forms

can be recognized by figures with broad shoulders and narrow waists, framed by elliptical pastel-colored

halos, and adorned with spired jewelry. Several dated examples from the early to mid-ninth century have

been found at Dunhuang.[7]

It has recently been suggested that Tibetan state patronage at Dunhuang can be found in Cave 25 of the nearby site of Yulin. This cave appears to be quite close to the “Treaty-Edict Temple” as described in ninth-century Tibetan documents found at Dunhuang. This temple was dedicated by the local Tibetan military government on the occasion of the signing of the Sino-Tibetan Peace Treaty of 822.[8] While the style of the paintings is a combination of Chinese and the new aesthetic introduced under Tibetan rule, there is a clear unifying political theme, that of the cakravartin ruler. The cakravartin, or a universal “wheel-turning king,” represented a concept of sacral rule in India whereby conquest by a devout king was thought to spread Buddhism, thus giving the ruler divine sanction to expand his empire (see chapter 2). This theme of sacrosanct rulership is stated in the Treaty Temple’s dedication, which is equated with building a divine palace, where the merit generated is dedicated to the Tibetan emperor “so that he can become a cakravartin ruler, exercising authority over the four continents and other kingdoms as well…”[9]

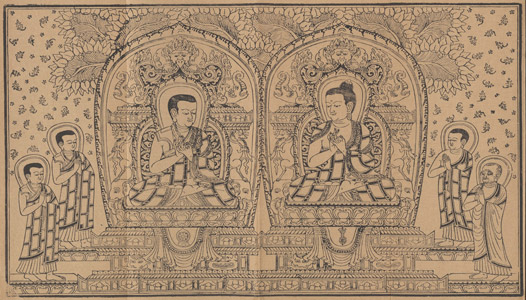

Fig. 1.3The painting of Vairocana and the Eight Great Bodhisattvas on the western wall of Yulin Cave 25 is based on distinct iconic models that emerged during Tibetan rule (fig. 1.3).[10] By the late eighth century, Vairocana became the center of a new Tibetan state cult in which the emperor was equated with the crowned Vairocana the Cosmic Ruler (see chapter 3).[11] This visual program was drawn from the Mahāvairocana-abhisaṃbodhi (“The Enlightenment of the Great Vairocana”), a text central to the officially sanctioned esoteric Buddhism of the Tibetan Empire. Evidence, such as catalogs of imperial collections, suggests that the Tibetan court had a special interest in Vairocana.[12] Indeed, at Samyé, Tibet’s first monastery, completed in 779, and a prominent court project of the period, esoteric Buddhism was first and foremost represented by Vairocana.[13] It has been suggested that the Tibetan Empire was viewed as an extended Vairocana maṇḍala, and that sites such as Yulin Cave 25 were intended to ritually mark the inclusion of the recently conquered Hexi area into the maṇḍala of the empire, with this form of Vairocana in particular intended to represent the presence of the Tibetan emperor.[14]

Fig. 3.4Several surviving rock carvings in the northern Sino-Tibetan borderland (Qinghai and Gansu area), dated to the early ninth century, depict Vairocana and the Eight Great Bodhisattvas, drawing on the same visual models found in Yulin Cave 25. One such carving was even associated with the same peace negotiations of 822 and lists the names of both Tibetan and Chinese artists.[15] Some of these carvings include visual expressions of this conflation of deity and ruler, with Vairocana depicted in the royal boots and robes of the Tibetan emperor (fig. 1.4).[16] Similar Vairocana imagery merging deity and ruler is even found after the collapse of the Tibetan Empire in the eleventh and twelfth centuries (see fig. 3.4), with the prominently crowned deity dressed in boots and royal robes adorned with distinctive Sasanian roundels associated with Tibetan royal figures. As early as the ninth century, inscriptions on rock carvings at Drak Lhamo in this region of the Sino-Tibetan frontier referred to the Tibetan emperor as a bodhisattva.[17] As vividly demonstrated by Brandon Dotson in chapter 3, images—especially sculpture—played an important part in both the imperial period and its memory, and the high-level patronage of Buddhism and its images during the imperial period was emulated by successor states as part of their claim to political legitimacy.

Fig. 1.4 |

Tantra and the Prototype of Charismatic Religious Rule

Fig. 1.5After the Tibetan Empire collapsed, there was a period of political fragmentation and chaos in Central Tibet, and the lack of a centralized political or religious authority gave rise to local tantric masters establishing their own authority.[20] Tantric practices popular in this period were characterized by a more explicit incorporation of sexual and violent imagery. These aspects of Mahāyoga, called union and liberation (sbyor sgrol), are techniques of power: the sexual practices are aimed at power over the internal realm of the body, and the violent practices are targeted at power over the external realm.[21] While the aggressive symbolism of these deities is presented primarily in terms of overcoming obstacles to liberation, these deities and practices were also expected to function for more mundane worldly ends, as can be seen in the second chapter of the Hevajra Tantra, which includes detailed descriptions of rituals to destroy an enemy army and even their gods.[22] Magical warfare, and the charisma of its mastery, became an important part of political legitimacy in the Tibetan Buddhist world.[23]

As institutional Buddhism began to regain its footing in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the image of the Tibetan emperor as a bodhisattva transformed into a potent religiopolitical symbol. The first to effectively appropriate this symbol of legitimacy by declaring himself a reincarnation of the Tibetan emperor was Lama Shang Tsöndrü Drakpa (1123–1194) (fig. 1.5).[24] Directly involving himself in political and military affairs, Lama Shang is himself a fascinating study in the political and martial employment of Vajrayāna (Tantric) Buddhism during the late twelfth century. Lama Shang ruled territory, enforced secular law, and conflated religious action with royal prerogative.[25] He even sent his own students into battle as part of their religious practice.[26] He characterized such actions as for the beneft of sentient beings, the bodhisattva ideal converted to political action in establishing order over chaos: “My warfare was in the service of the Teaching; not for a single moment did I do it for my own personal interest.”[27] This bellicose behavior was not without controversy among Tibetan leaders, even among his own Kagyü order, and the First Karmapa himself was dispatched in an attempt to rein in Lama Shang’s behavior.[28]

Fig. 8.3Equipped not only with conventional weapons, Lama Shang also employed a ritualized warfare of magic spells, aided by powerful protector deities such as Śrī Devī and Mahākāla (see chapter 8 and fig. 8.3).[29] Interestingly, Lama Shang’s own small Kagyü monastic suborder, the Tsalpa, had direct ties to the Tangut court, the next political polity to rise to prominence. The Tangut imperial preceptor, Tishrī Repa Sherab Sengé (1164–1236), while ethnically a Tangut, trained with Lama Shang.[30] Lama Shang’s tutelage helped lay the foundations for the Tangut imperial preceptor’s involvement with the cult of the wrathful protector deity Mahākāla as a means for worldly power.

TANGUT KINGDOM OF XIXIA

The Tangut court of Xixia (1038–1227), a small but powerful multiethnic kingdom along the Silk Road, established many of the imperial practices of Tibetan Buddhism and art later emulated by larger regimes, especially the Mongol Empire.[31] Tibetan and Chinese religious and artistic traditions were integrated through Tangut patronage, creating a new visual model of sacral rule that included both political and artistic forms. These later became characteristic of imperial engagement with Tibetan Buddhism, continuing into the early twentieth century.

The Tangut Empire of Xixia, an expansionist state between Tibet and China on the Silk Road, included large Tibetan and Chinese subject populations. The Tanguts drew heavily on Chinese models in establishing their own imperial culture, including governmental administration and a writing system. However, with the fall of the Northern Song dynasty in 1127, coupled with the dynamic revival of Buddhist activity in Tibet in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the Tanguts turned increasingly west to the Tibetan realm for guidance. Shortly after the incorporation of Tsongkha territories into Xixia, the custom of a Tibetan Buddhist monk serving as imperial preceptor at the Tangut court was established. Indeed, the Tanguts seemed engaged with all the major religious centers in Central Tibet, especially those of the Sakya and Kagyü orders.[32] Buddhism served the state in legitimization and engendered lavish imperial patronage, with the Tangut emperors presenting themselves as sacral cakravartin rulers. Among the northern nomads, the Tangut emperors were known as the Buddha Khan (Burqan Khan).[33]

Fig. 4.7The Tanguts employed a self-conscious multicultural strategy, editing texts in three languages at once: Tangut, Chinese, and Tibetan. In their art, one also sees a mixing of both Chinese and Tibetan iconographic and stylistic traditions to meet the Tangut patron’s particular needs. This blending is evident in objects excavated from Tangut sites such as Khara Khoto, as well as caves dating to their rule of Dunhuang, which the Tanguts absorbed in 1036. One hallmark of the Tangut court was lavish silk images, such as cut silk (kesi 缂丝; btags sku) (see figs. 4.7 and 4.11), a technique developed in Central Asia and adopted by the Tangut court for the making of Tibetan Buddhist icons. The Tanguts were the source of many such imperial court practices integrating Tibetan Buddhist imagery with Chinese media and artistic techniques that would be emulated for centuries. The continued debate in distinguishing Tangut Xixia and Mongol Yuan objects, especially in silk, speaks to the close relationship between these two court traditions and the continuity of this visual production from the twelfth into the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.[34]

Fig. 1.6 The printed icon of a wrathful deity excavated from the Tangut site of Khara Khoto bears invocations that make its political role clear (fig. 1.6). On the right, it reads: “Long Life to the Emperor!”; and on the left: “Peace to the People, Grandeur to the State!”[35] The wrathful deity Mahākāla became a special focus of Tangut imperial Buddhism. Mahākāla is a powerful Buddhist protector deity, a manifestation of divine wrath used in removing obstacles, and considered especially effective in military applications. For instance, one Tibetan Buddhist cleric who is tied to the Tangut imperial line, Tsami Lotsawa (fl. twelfth century), is linked to at least sixteen texts on Mahākāla, including one called The Instructions of Śrī Mahākāla: The Usurpation of Government—a short “how-to” work on overthrowing a state and taking power.[36]

The Tangut Roots of Mongol Engagement with Tibetan Buddhism

Mongol interests in Tibetan Buddhism can be traced to their potent encounter with the ferce deity Mahākāla through their military campaign against the Tangut Empire of Xixia in the early 1200s.[37] By the time of the Mongol invasion, Tibetan clerics served as imperial preceptors at the Xixia court, where Mahākāla was a focus of Tangut court Buddhism. Chinggis (Genghis) Khan first laid siege to the Tangut capital in 1210. According to Tibetan texts, when Lama Shang’s student Tishrī Repa, the Tangut’s Tibetan court chaplain, summoned Mahākāla (see fig. 8.3) to the battlefield, the dams the Mongols were using to flood the city burst, sweeping away Mongol troops and forcing Chinggis to withdraw.[38] This account of their unusual military setback through effective religious ritual no doubt caught Mongol attention. Later, the Buddhist model of cakravartin sacral rule and the cult of the wrathful protector deity Mahākāla, both ministered by Tibetan clerics, were adopted by the Mongolian state.

MONGOL EMPIRE

The Mongols established the largest contiguous empire in world history (ca. 1206–1368), covering most of Eurasia from the Pacifc Ocean to the eastern Mediterranean. The Mongols conquered most of Asia in the thirteenth century, thereby bringing Tibetan visual culture to the Chinese heartland. Qubilai Khan declared his dynasty the Great Yuan (1271–1368), based on a Chinese model, within the larger Mongol Empire, with Qubilai at the center as Great Khan.[39] The Mongols relied heavily on peoples from other areas of the empire, such as the Uighurs, Tanguts, and Tibetans. While the Mongol Empire was known for a policy of religious tolerance among its peoples, as well as generous patronage across a broad spectrum of religions, Qubilai singled out Tibetan Buddhism among the faiths competing for court attention. Evidence suggests that Mongol interests in Tibetan Buddhism lay in both a model of sacred rulership that allowed them to unite an empire across ethnic and clan divides, and the corresponding esoteric means to physical power—ritual magic—that could be harnessed to serve the Mongol imperium. Their interest in Tibetan Buddhism was actually quite practical, even utilitarian.

Tibetans as Imperial Preceptors

Patronage of various Tibetan lamas and schools was initially divided among different Mongol appanages, including territorial fiefs (Sakya to Köten Khan, Phakmodru to Hülegü, Tsalpa to Qubilai, and the Karma Kagyü to Ariq-Böke), and their monasteries flourished as never before.[40] Tibetan Buddhism prevailed in many parts of the Mongol Empire, including the early Mongol Ilkhans in Persia.[41] Long before the founding of the Yuan, Köten Khan summoned one of the great Tibetan scholars of the time, Sakya Paṇḍita (1182–1251) (see fig. 5.2), and had him escorted, along with his two nephews as hostages, to the Mongol court as representative of Tibetan interests. Two years later, when Möngke Khan (r. 1251–1259) gave the former Tangut territory to Qubilai, he also took possession of Sakya Paṇḍita’s nephews, one of whom was the Tibetan cleric Phakpa (1235–1280) (see figs. 5.3–5.5).

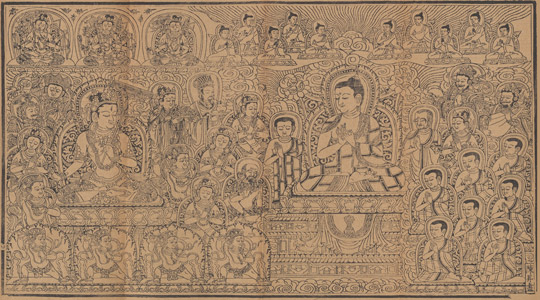

Fig. 1.7

Fig. 5.6 In 1260, Qubilai declared himself Great Khan, leading to civil war and the fragmentation of the Mongol Empire, with Qubilai maintaining control of Asia. Phakpa initiated Qubilai into Tibetan Buddhist rites, and in turn Qubilai, as an offering to his lama, granted Phakpa suzerainty of Tibet. Not dispensing with realpolitik, however, Mongols militarily occupied Tibet, with Sakya authority dependent on Mongolian garrisons. Later, when Qubilai Khan declared the founding of the Yuan dynasty, he made Phakpa imperial preceptor, the highest religious authority in the land. As part of his investiture, he had the crystal seal of the Tangut emperor re-created for Phakpa, likely in emulation of Tangut court ritual.[42] This action gave symbolic weight to the Mongols as conscious inheritors of the Tanguts in a patron-priest relationship with the Tibetans. Phakpa also developed a new script based on Tibetan, called Phakpa script (see chapter 5), to phonetically render all the disparate languages of Qubilai’s empire; it was employed on official documents and insignia, such as seals and passports (see fig. 5.6). Significantly, Qubilai Khan also had Phakpa tutor his heir apparent, Jingim (Zhenjin 真金, 1243–1285).[43]

It has recently been suggested that some of these key political moments—as understood by later Tibetans—were depicted in two portraits of Phakpa: the initiation of Qubilai Khan and his granting of Tibet to Phakpa as part of offerings in 1264 (see fig. 5.4) and Phakpa being appointed imperial preceptor by Qubilai Khan around 1270 (figs. 1.7 and 5.5).[44] In the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria painting, note Qubilai Khan and his wife, Chabi, herself known for her devotion to Tibetan Buddhism and Phakpa in particular, are depicted smaller, to Phakpa’s left, and her hands are clasped in reverence. Observe the meticulous care in the depiction of Qubilai and Chabi, with her hat topped with a peacock feather. A Chinese official holding his tablet of office and paying homage in the bottom corner is likely one of Qubilai Khan’s close Chinese court advisors, such as Liu Bingzhong 劉秉忠 (1216–1274), upon whom Qubilai depended greatly in his early career. In 1264, while Liu Bingzhong was a monk, he was ordered to wear appropriate robes at court and even marry.[45] The court sponsored memorial halls for Phakpa throughout the empire, and in 1324, eleven painted portraits of Phakpa were distributed to the provinces so clay statues could be modeled for worship.[46]

Until the fall of the dynasty in 1368, it became Yuan practice to appoint Tibetans as imperial preceptors. This relationship between the Mongol emperor Qubilai and his Tibetan chaplain Phakpa, often characterized as a patron-priest relationship, became a model that subsequent imperial courts and Tibetans would invoke for centuries to come.

Mahākāla as State Protector

Fig. 5.8 The fierce deity Mahākāla was made protector of the Mongol Empire and became a focus of the Mongol state (figs. 1.8 and 5.8).[47] Applications of Mahākāla in service of the Mongolian military machine are well attested in historical sources, and in recognition, many temples and images dedicated to Mahākāla were built throughout the empire. The Mongols attributed many victories to the summoning of Mahākāla. For instance, when the Mongol army first marched south, the Chinese petitioned the Chinese martial god Zhenwu 真武 to deliver them from the Mongol onslaught. The god purportedly responded that he had to hide from the Great Black God leading the Mongol army. The Chinese cities surrendered.[48]

Fig. 1.8 Most famously, in 1275 Qubilai asked Phakpa for Mahākāla to intervene against the Southern Song, which his greatest general Banyan (Bayan; 1236–1295) could not conquer. The Nepalese artist Anige constructed a temple south of Beijing at Zhuozhou 涿州 with its statue facing south, and soon after the Song capital fell. When the former emperor of Song and his courtiers were brought north, they were astonished to see the image of Mahākāla just as they had seen him among the Mongol troops. These accounts of the Southern Song collapse are recorded in both Chinese and Tibetan sources.[49]

This sculpture of the Tibetan protector used to conquer the Song became a potent symbol of both Qubilai’s rule and the Yuan imperial lineage. This association was so strong that even four centuries later, in 1635, the Manchus, lacking the proper bloodlines, traced their own spiritual ancestry to Qubilai Khan as the rightful inheritors of his Yuan legacy and installed this statue of Mahākāla in their own imperial shrine. While this famous statue disappeared with the fall of the Qing dynasty, an Indic stone sculpture dated to the same period (1292), preserved in the Musée Guimet in Paris (see fig. 1.8), records in its inscription that the donor was a close disciple of the Imperial Preceptor Phakpa, who enjoyed the protection of Qubilai Khan:

As for this sculpture, in order to spread the precious teachings of the Buddha far and wide and endure for a long time; to pacify obstacles to the lives of all the great patrons and priests; and to destroy all enemies, the one called Atsara Pakshi (“the learned master/magician”), who is close attendant and protected by the kindness of the dharmarāja called Phakpa, eminent guru and second Buddha of [this] degenerate age, and [protected by] that widely renowned great khan called Qubilai, king who rules nearly all of the world, acted as patron. The master artist unrivaled in this field of knowledge, called Könchok Kyap, having served, successfully accomplished it in the Water Male Dragon Year (1292). May you enjoy great prosperity![50]It is likely that this “learned master/magician” was none other than Qubilai Khan’s primary Mahākāla ritual specialist, the Tibetan monk Dampa (1230–1303), who was recognized as an emanation of Mahākāla on earth, credited with aiding many Mongol military victories through his summoning of Mahākāla.[51] Indeed, many of the feats attributed to Mahākāla cited above come from Dampa’s Chinese biography, which asserts, “This is proof of how he aided the state.”[52] This sculpture thus embodies the religiopolitical relationship at the heart of Tibetan involvement at the Mongol court, and it is likely Dampa who is depicted as a swarthy monk attending below Phakpa (see fig. 5.5) in audience with Qubilai Khan, thus re-creating this troika of religiopolitical power evoked in the sculpture’s inscription.

A prominent Mongolian patron of this imperial Mahākāla tradition was Grand Princess Sengge Ragi (ca. 1283–1332), most famously known as a collector of Chinese art and often touted in Chinese art-historical discourse as a heavily sinifed Mongol who took on the identity of a Chinese literatus.[53] Princess Sengge was also an avid patron of Tibetan Buddhism, the state Mahākāla cult, Protect the Nation Temple 護國寺, and Dampa in particular, indicating she did not give up her Mongolian identity; rather her behavior suggests the existence of a Mongolian elite that could move skillfully among the diverse cultural circles that composed their multiethnic empire.[54]

The Nepalese Head of Imperial Workshops: Anige

Fig. 1.9

Fig. 1.10 A special appreciation and dispensation for craftsmen under Mongol rule, first established by Chinggis Khan, continued under Qubilai, and the arts flourished under Mongolian patronage. Phakpa recommended a young Nepalese artist named Anige 阿尼哥 (1244–1306) for service at the Mongol court. Anige so impressed Qubilai Khan that he quickly rose to supervisor-in-chief of all artisans at court. He was commissioned to produce a variety of buddhas and stūpas in the imperial capitals of Shangdu and Dadu (Beijing), steel dharma wheels—the symbol of the cakravartin universal ruler—to use as imperial standards, and portraits in silk of Qubilai and Chabi for the imperial temple. Anige’s most visible imprints on the Chinese landscape are two majestic white stūpas, one in the imperial capital Beijing, built in 1279 (see fig. 5.7), and the other on Mañjuśrī’s sacred mountain of Wutai shan (Mount Wutai), completed in 1301 (see fig. 9.1). Many of these Yuan works have been lost, and no piece has yet been reliably attributed to Anige.[55] Other surviving objects, however, bear a distinct Nepalese aesthetic, made in Chinese luxury mediums newly employed for the creation of Tibetan Buddhist images during the Yuan, including dry lacquer (fig. 1.9).[56] Chinese sources tend to broadly describe this new imperial idiom as fan xiang 梵像, which might be rendered as “Indic images,” seeming to conflate the Indian, Nepalese, Tibetan, and Tangut modes that informed it (fig. 1.10).

Silk: Vajrabhairava (ca. 1328–1329)

Fig. 5.9Tibetan Buddhist icons lushly produced in the same silk technique popular in the Tangut court, kesi, became a signature of Mongol imperial court production. An exquisite example is the monumental maṇḍala in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (see fig. 5.9). Its large scale is consistent with records of Yuan imperial commissions.[57] Political intrigue surrounded the Mongol imperial figures who are depicted in this artwork (see figs. 5.10 and 5.11), and their stories and titles are fascinating aids in helping us contextualize this magnifcent object. “King” Tuq-Temür, the son of a Tangut empress, came to power as the result of a coup d’etat in 1328. His older brother, here named “Prince” Qoshila, only reigned briefly, from February 27 to August 30, 1329. Tuq-Temür’s entourage assassinated him out of fear of his military strength and the resulting Chaghatayid Khanate influence on the Yuan dynasty.[58] Tuq-Temür was then re-enthroned, but he died of disease three years later. The titles in the Tibetan cartouches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s silk suggest that at the time of its production “King” Tuq-Temür was already named Khan, which had occurred in September 1328, but “Prince” Qoshila had not yet been enthroned, an event that took place in February 1329. These titles therefore place the silk’s design—if not creation—to late 1328 or early 1329. For more on this fascinating textile, see chapter 5.

Stone: Feilaifeng (1282–1292)

Fig. 1.11 After the Mongols conquered and absorbed the Tanguts in 1227, members of the Tangut clergy continued to be employed under the Mongols. The Tangut’s versatility—being adept at Tibetan and Chinese linguistic, doctrinal, and artistic traditions—was no doubt valued by the Mongols in both forging and implementing the political and religious policies of their own empire, which followed several Tangut precedents. The most prominent example is the notorious Minister Yang Lianzhenjia 楊璉真伽 (Rinchen Kyab; d. 1291), who was made head of the Bureau of Religious Affairs of Southeast China in 1277. His sponsorship reflected a focus on subduing newly conquered territories by building stūpas and reestablishing former Buddhist monuments, including some on the sites of Daoist temples, former Song palaces, and even imperial tombs. His activities in the Hangzhou area included commissioning stone sculptural niches carved directly into the local landscape at Feilaifeng 飞来峰, dating to about 1282 to 1292. The statues vary from being completely Chinese in appearance, such as the famous reclining Budai Maitreya, to deities clearly based on Tibetan artistic models, which were dominant in both the Tangut and Mongol courts, such as the majestic Uṣṇīṣavijayā (fig. 1.11).[59] Many of these thirteenth-century images are a fusion of the two traditions, featuring Tibetan iconography like five-leaf crowns sitting atop rounded Chinese faces.

Printing: Qisha Canon (ca. 1302)

Fig. 1.12 |

Fig. 1.13 |

Fig. 1.14 Further evidence of Mongol court adaptation and the continuation of Tangut practice was the enormous undertaking of printing the Tangut edition of the Buddhist canon (ca. 1301–1302) in Hangzhou, one of China’s largest and most important printing centers. The frontispiece designs were repurposed for other printing projects, such as the massive Qisha Canon 磧砂藏 (ca. 1302), sponsored by the aforementioned Tangut Minister Yang and overseen by the Tangut Guan Zhuba 管主八 (Bka’ ’gyur pa) (figs. 1.12 and 1.13).[60] These productions incorporated many translations of Tibetan texts, such as Phakpa’s advice to Qubilai’s son, the crown prince. However, many of the Tibetan texts added into the Chinese Buddhist canon during the Yuan dynasty were either translated by Tanguts serving in the Mongol administration, such as Shaluoba 沙囉巴 (Shes rab dpal; 1259–1314), or had already been translated under the former Tangut Kingdom of Xixia.[61] Nine of the ten known frontispieces made for the Qisha Canon show a distinct mixing of Tibetan and Chinese imagery and are similar to both the 1302 Tangut canon and extant Tangut xylographs.[62] These frontispieces were separate blocks and could have been printed with any number of texts, so their woodblocks would have worn out quite quickly and required re-carving many times, making it difcult to date the printings or say which ones are original.[63] Nonetheless, they appear to be faithful representatives of the early fourteenth-century images, some of them even preserving the names of the original Chinese illustrator Chen Sheng 陳昇 (see fig. 1.13) and carver Chen Ning 陳寧.

Architecture: Juyongguan (1345)

Even as late as 1345, over a century after the fall of Xixia, Tangut script is found on politically significant geo-religious monuments such as the Juyongguan 居庸关 stūpa gate to the north of Beijing (fig. 1.14). It was constructed on the order of the last Mongol emperor and supervised by the Tibetan cleric Namkha Sengé. Such gates were used to mark the cardinal directions in delineating the sacred space of a city, similar to those found in depictions of the divine realm of a deity’s palace (maṇḍala). A number of the various inscriptions in Sanskrit, Tibetan, Mongolian Square script (Phakpa script), Chinese, Tangut, and Uighur lining the walls of the gate declare Qubilai Khan as an emanation of Mañjuśrī, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, establishing the sacral nature of his rulership and empire. There has been debate about whether Qubilai was regarded as Mañjuśrī in his own lifetime.[64] But there is evidence of contemporary Tibetans questioning the validity of this identifcation, suggesting he was recognized as Mañjuśrī; they essentially argued, “If he is a bodhisattva, why does he need to use violence and intimidation?”[65] Regardless, Qubilai Khan’s image as Mañjuśrī became especially significant when the Manchus conquered China in 1644 and declared themselves Qubilai’s spiritual and political inheritors as emanations of the same deity.[66]

CHINESE MING DYNASTY

Fig. 1.16 Even after the Mongol Yuan dynasty collapsed and the Chinese reclaimed their land, establishing the native Ming dynasty (1368–1644), the Chinese court continued to follow Mongol precedents for an imperial Buddhist vocabulary symbolic of divine rule. By this time, Qubilai Khan’s model of rulership was recognized across Asia; the early Ming rulers employed the accepted language of power to declare their authority.[67] This has not been the traditional understanding of the Ming, who are said to have expended a great deal of energy to reassert an ethnic Chinese identity in the wake of Mongol rule. Yet Tibetan Buddhism continued as a faith of the powerful within the inner court. A lot of Tibetan Buddhist art was created in the Ming imperial workshops, both for internal court use and as diplomatic gifts (figs. 1.15, 1.17, 6.3, and 6.15).

-318.jpg)

Fig. 6.4 Engagement with Tibetan Buddhism was a defning aspect of imperial identity for the first half of the Ming.[68] The Yongle emperor (r. 1403–1424) was the Ming ruler who most famously engaged with Tibetan Buddhism. As a prince, he was well versed in the ways of the previous regime and was known to the Tibetans before coming to power. However, Yongle was not the crown prince; he had seized the throne from his nephew, thus his reign fell under a cloud of doubt. As part of a strategy to underline his right to rule, Yongle invited the Karmapa, who served as the final Tibetan preceptor to the Mongols before the collapse of the Yuan, to come to the Ming court to perform mortuary rituals for his deceased parents (figs. 1.16 and 6.1). He even suggested re-creating the relationship between Qubilai and Phakpa in the Karmapa and himself. After the Karmapa’s visit, Yongle indeed styled himself a cakravartin universal ruler. The production of Tibetan Buddhist art at court reached its apex under Yongle, most famously in the elegant gilt bronzes bearing his reign mark (see figs. 1.15 and 6.3). The Chinese luxury medium of silk textiles also continued to be a staple of Ming imperial court production of Tibetan icons (see figs. 6.4 and 6.5).

The Yongle emperor was by no means the most ardent Ming ruler in his adoration of Tibetan Buddhism. Emperor Wuzong 武宗 (r. 1506–1521) was an enthusiastic, zealous patron. He studied Tibetan language, dressed as a Tibetan monk, kept many Tibetan monks around him, and built a Tibetan Buddhist temple in the Forbidden City. He even declared himself an emanation of the Karmapa lamas, which was not well received by the Tibetans.

Fig. 1.17 Eunuchs were important conduits between the Ming imperial court, Tibetan patriarchs, and artistic production, since they served as personal attendants to the emperor, envoys to Tibetan patriarchs, and managers of the court ateliers. Their influence is reflected in their private temples in the capital as well as imperially sponsored monasteries, whose construction they oversaw on the Sino-Tibetan border. Such temples can be viewed as sites of political propagation and cultural negotiation, both in the capital and as projections of Ming imperial power into contested borderlands, conveyed through a mixture of Chinese imperial architecture and an international Buddhist visual vocabulary (figs. 1.17 and 6.15). In the border regions, these temples were part of a larger strategy to gain a foothold along the Ming-Amdo frontier. The locally venerated Tibetan Buddhist leaders of these temples also performed diplomatic functions, such as negotiating disputes between the Ming and the Mongols, with whom Tibetans would soon have an increasingly significant relationship.[69]

Second Conversion of the Mongols

In the late sixteenth century, the Mongols underwent a second, more deeply rooted conversion to Tibetan Buddhism, a conversion so thorough that the religion became essential to Mongolian identity. This historical turning point in Inner Asian politics had far-reaching consequences for generations (see chapter 10). Tibetan Buddhism became a cultural and political rallying point for the fractured Mongols and Inner Asian groups, once again aiding in empire building. From this point until the modern period, the Mongols played a key role in the politics of Tibet, Tibetan relations with China, and imperial interest in Tibetan Buddhism. Indeed, the lingua franca among these cultures was often Mongolian.

Although Tibetan Buddhism was important for the Mongolian imperial elite in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, when the Mongols returned to the steppe their connections to the Dharma waned. Yet one ambitious leader, Altan Khan (1507–1582), saw promoting Tibetan Buddhism as a strategy to overcome the tradition of primogeniture and thereby legitimate his power.[70] To these ends, Altan Khan invited a number of Tibetan teachers to proselytize among his people, including a famous monk of the relatively new Geluk monastic order, Sönam Gyatso (1543–1588). Altan Khan was so impressed with the monk that he gave him the title Dalai Lama (“Oceanic Guru”), retroactively known as the Third Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama in turn declared Altan Khan to be a reincarnation of Qubilai Khan, tremendously boosting Altan’s status among the Mongols.[71] The next (fourth) incarnation of the Dalai Lama was then recognized in the grandson of Altan Khan, a shrewd political move that bound the Mongols closely to Geluk interests. The Mongols became fercely loyal to the Geluk order and were instrumental in establishing the Dalai Lama’s political rule over Tibet in the seventeenth century. Repeated Mongolian incursions, however, were not welcomed by many Tibetans, which resulted in a cottage industry of ritual war-magic specialists known as Mongol-repellers (see chapter 8).

Fig. 7.2

Fig. 7.5 Rise of the Dalai Lamas (1642–1959)

The system of succession through reincarnation became an important means of political legitimacy in Tibet. It is no better exemplified than by the Dalai Lamas, who came fully to power by Mongol military support in 1642, becoming the first theocratic rulers of a unifed Tibet, which had been fractured since the collapse of the Tibetan Empire eight centuries earlier. As discussed in chapter 7, an important part of the Fifth Dalai Lama’s (1617–1682) claim to power was promoting himself as an emanation of Avalokiteśvara, thus conflating himself with the first Tibetan emperor and positioning the Dalai Lamas as the rightful inheritors of the Tibetan Empire (see figs. 7.2 and 7.5). The Dalai Lamas and their regents widely publicized this connection through text and image, making it a major theological underpinning of the government, which ruled Tibet until 1959.

In the Fifth Dalai Lama’s History of Tibet, written the year after he came to power in 1643, the Tibetan imperial period is described as a golden age, the time of the establishment of Buddhism in Tibet by a series of divine religious kings, who were in fact bodhisattvas incarnate (see chapters 3 and 7). By identifying himself as an incarnation of the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara, the Dalai Lama employed a language of divine inheritance, the succession of past glorious empires through the mechanism of reincarnation.[72] This choice was politically charged, because the founder of the Tibetan Empire, Songtsen Gampo (ca. 605–649), was by the eleventh century also considered Avalokiteśvara’s emanation, visually expressed by the small Buddha Amitābha’s head peeking out of the emperor’s turban (see figs. 3.2 and 3.7). To reinforce this association, the Dalai Lama built his own massive seat of power on the same hill overlooking Lhasa, Red Hill (Marpori), where the palace of the Tibetan emperors of old once stood. He named it Potala after the earthly abode of Avalokiteśvara (see fig. 7.8).

Another visual means by which the Fifth Dalai Lama and his government promoted this connection was with images of his previous incarnations, through large murals in his palace and series of thangka paintings. One such series includes a painting of Songtsen Gampo framed by the Dalai Lama’s own hand and footprints, making a direct visual statement about their conflated identities and, by extension, the Dalai Lama’s political authority (see figs. 7.2 and 7.5).[73]

The next emperors to rule China, the Manchus, also employed this unique form of Tibetan theological statecraft. Indeed, early instances of the Manchu emperors being referred to as the Mañjughoṣa emperors (’jam dbyangs gong ma) are found in letters from the Fifth Dalai Lama to the Qing founder, Hong Taiji, in the 1640s and 1650s, the timing of which suggests a political subtext: “Tibet is ruled by Avalokiteśvara (me) in the west, and China is ruled by Mañjuśrī (you) in the east, separate but equal.”[74] These words correspond to the Buddhist tradition of linking specifc deities to specifc regions: China with Mañjuśrī, Tibet with Avalokiteśvara, and Mongolia with Vajrapāṇi—together known as protectors of the three lineages.

MANCHU QING DYNASTY

Fig. 1.18Like the Mongols, the Manchus conquered China from north of the Great Wall, adopting Tibetan Buddhism as a means of political legitimacy to rule their vast multiethnic empire. During their Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Tibetan Buddhism was once again an official religion of the empire. Under the Manchus, the visual language of Buddhist imperial rule was further refined and the concepts of sacral legitimacy given a finer point, with a special focus on the cult of Mañjuśrī (see fig. 6.3). The Manchu emperors, lacking the proper bloodlines to the Mongol ruling house, traced their own spiritual ancestry to Qubilai Khan through the Tibetan succession mechanism of reincarnation. By promoting themselves as emanations of Mañjuśrī, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, they declared themselves Qubilai Khan reborn, rightful inheritors of his Yuan legacy. This Manchu inheritance of Qubilai’s realm was propagated through the production of religious art (see chapter 9).

This identity was especially significant because the incorporation of the Mongols into the Qing dynasty was critical to the Manchu state’s survival; both the Chinggisid lineage of Qubilai Khan and Tibetan Buddhism were powerful symbols in the Mongol political vocabulary of the seventeenth century.[75] This was but one of several mutually reinforcing strategies aimed at various subject and neighboring peoples in establishing and solidifying the Manchu Empire in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The rulers adopted certain personae to transform themselves into the representatives of those peoples, whether Chinese or Mongol, Confucian or Buddhist, legitimizing their position and appropriating those cultures by masking their image as outsiders who had in fact conquered them.[76]

In 1635, shortly before the Manchus completed their conquest of China, the first Qing emperor, Hong Taiji (r. 1626–1643), changed his people’s ethnonym from Jurchen to Manju (Manzu 满族), an etymology that seems to have been engineered from Mañjuśrī.[77] While both Tibetan and Mongol sources made the Manchu-Mañjuśrī connection as early as Hong Taiji’s reign, more than any other Manchu ruler it was the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736–1795) who realized the potential of patronizing Tibetan Buddhism, evidenced by the incredible volume of Tibetan Buddhist images produced by his imperial workshops. Some of the most politically pointed images included paintings depicting Qianlong as an emanation of Mañjuśrī and by extension Qubilai Khan (fig. 1.18). They bear the traditional Tibetan iconography of a book and sword at his shoulders, visually marking him as Mañjuśrī, as well as Tibetan inscriptions that unequivocally declare him as “the sagacious Mañjuśrī, the great being who manifests as lord of men, king of the dharma, may he be steadfast on the vajra throne . . .”[78] The Italian Jesuit court painter Giuseppe Castiglione (1688–1766) realistically painted Qianlong’s unmistakable visage. In his lap Qianlong holds the golden wheel of the sacral cakravartin ruler.

Fig. 9.2 The Qianlong emperor’s court chaplain, Changkya Rölpai Dorjé (1717–1786) (see fig. 9.2), had a guiding hand in the formation of this Sino-Tibetan imperial Buddhist art that came to symbolize Manchu rulership. From childhood, Rölpai Dorjé was educated with the imperial princes, and together they studied Buddhist scripture as well as Chinese, Mongolian, Manchu, and Tibetan. This close contact between a monk and emperor from such an early age was unprecedented. Rölpai Dorjé’s incarnation lineage was carefully crafted to reflect the notion that the patron-priest relationship between Qubilai and Phakpa was reborn, quite literally, in Qianlong and himself.[79] In 1745, Rölpai Dorjé initiated Qianlong into the rites of a divinely anointed sovereign (cakravartin), just as Phakpa had done for Qubilai. Later, when Rölpai Dorjé translated Phakpa’s biography into Mongolian in 1753, he drew a direct parallel between the two acts, ruminating that he and the emperor had been connected through many lifetimes, and he stated directly that Qubilai was the predecessor of Qianlong in the Mañjuśrī incarnation lineage.[80] A Tatar (Mongol) official told the British diplomat Lord Macartney during his 1793 embassy that the Qianlong emperor was an incarnation of Qubilai Khan, suggesting this association was well known.[81]

Fig. 9.3Rölpai Dorjé became Qianlong’s religious teacher and close political confidant, helping the emperor craft a policy toward Tibet and Mongolia that underscored the Manchu inheritance of Qubilai’s realm, both politically and symbolically, through the production of religious art. Rölpai Dorjé produced the definitive iconographic guides for artists, established a workshop of thangka painting in Beijing, and oversaw the production of Buddhist images in the imperial workshops (see figs. 1.18, 9.3, and 9.9–9.15). These images were carefully presented during Qianlong’s reign in the Chinese court, using the power of symbols to bolster Manchu legitimacy as the successor to the Yuan Empire. Rölpai Dorjé’s role in the production of Tibetan Buddhist images is particularly interesting in light of their politically symbolic position in the Qing court and his own function in that same context as an incarnation, a living object of legitimization.

Later Aspirations for the Revival of a Mongol Empire

Aspirations for the revival of the former glories of the Mongol Empire were grounded in a Buddhist framework. The famous artist and first Jebdzundamba incarnation, Zanabazar (1635–1723)—Mongolia’s first incarnate lama, leader of Mongolian Buddhism, and direct descendant of Chinggis Khan—became a focus of these aspirations for the eastern (Khalkha) Mongols (see fig. 10.2).[82] The Jebdzundambas were seen as emanations of the bodhisattva Vajrapāṇi, patron deity of Mongolia, and central to Khalkha Mongolian identity. In Mongolia, Zanabazar was initially recognized as the incarnation of an important, controversial Tibetan hierarch, Tāranātha (1575–1634), whose Jonang tradition had been banned by the Fifth Dalai Lama after the civil war, in part for his deployment of magical warfare against the Ganden Phodrang government and its Mongolian allies at the behest of his patron. When Zanabazar arrived in Central Tibet, the Dalai and Panchen Lamas welcomed him as the rebirth of an important Geluk figure, Jamyang Chöjé (1379–1449), founder of Drepung Monastery. This identifcation then supplanted the Jonang identity in the Geluk narrative, effectively co-opting his lineage. It seems that during Zanabazar’s ten years of training at Tashilhunpo Monastery, he was exposed to Newari sculptors who were then working for the Panchen Lama.[83]

Fig. 1.19When Zanabazar returned to Mongolia, he brought with him fifty religious specialists, establishing Geluk traditions at his new monastic capital at Urga (present-day Ulaanbaatar).[84] In his biographies there are no references to art or sculpture before his trip to Central Tibet, but upon his return he began to make remarkable sculptures (figs. 1.19 and 10.3). A standing bodhisattva Maitreya sculpture closely resembles a famous statue made by Zanabazar for the annual Maitreya Festival procession, which he established in Urga (see fig. 10.4). The Maitreya statue is therefore an object of public veneration. Zanabazar’s Nepalese-inspired Maitreya compositions are characterized by a soft sleekness of form broken by a subtle asymmetrical linear pattern of cords and sashes. The gentle contrapposto pose, accentuated by the flare of the hem of his clinging drapery, the tiny antelope skin draped over his left shoulder, the unusually tall pile of hair to accommodate the stūpa on his head, and the distinctive articulation of the lotus flower on which he stands are all hallmarks of Zanabazar’s design. Maitreya, the Buddha of the Future, is a special object of worship among the Mongols, his advent ushering in a new age and perhaps a return to the glory of the Mongol Empire.

The Mongols, however, were not united. Galdan Khan (b. 1644, r. 1678–1697), ruler of the western (Zünghar) Mongols, challenged the Manchus for domination of Inner Asia, positioning himself as defender of the Dalai Lama’s interests. He saw the rising status of Zanabazar as a threat to the Dalai Lama’s supremacy among the Mongols.[85] Galdan led his Zünghar Mongols to attack the Khalkha, plundering and burning temples and images, including Erdeni Zuu, the first monastery in Mongolia. Unable to repel these Mongols, Zanabazar convinced the Khalkha nobility to submit to the Manchus for protection, thus surrendering the dream of an independent Khalkha Mongol state led by the incarnate lama. When the Zünghars were eventually defeated and absorbed into the Qing state, Zünghar prisoners revealed the Fifth Dalai Lama’s long-concealed death, shattering the Tibetan regent’s authority. The Manchu Kangxi emperor and Zanabazar had had a close relationship. But when the second Jebdzundamba was implicated in a rebellion against the Qing, the Manchus forbade later incarnations to be found among the Mongols. The Manchus seemed to fear joining Chinggisid political power with religious authority, with reincarnation providing the link.

Fig. 10.5After the Qing Empire absorbed the Mongols, a different Buddhist rhetoric was employed to serve the Manchu state. By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it was especially focused on the cults of the future buddha, Maitreya, and the apocalyptic myth of the kingdom of Shambhala (see chapter 10). Shambhala is believed to be a hidden land where the kings are guardians of the Kālacakratantra, which contains a prophecy of a future holy war. At the end of this world cycle, when barbarians have taken over the earth, the last king of Shambhala will ride forth with his armies to destroy the nonbelievers, ushering in a new golden age. It became the goal of Mongols to be reborn in Shambhala to fight in that epic battle. Special Kālacakra temples were built, with large paintings near the entrances depicting Shambhala and the battle (see fig. 10.5). In these temples, monks performed rituals to speed the coming of this new Buddhist age. When various rebellions from Muslims, Christians, and others threatened the Qing, this Shambhala myth was used to mobilize Mongols to aid the failing Qing state.[86]

Conclusion

Tibetan Buddhism’s dynamic political role acted as a major catalyst in moving the religion beyond Tibet’s borders to the Tangut, Mongol, Chinese, and Manchu empires, where its art helped greatly in claiming power, both symbolic and literal. Grounding Tibetan Buddhism and art in their historical contexts reveals that such political aspects of the tradition are essential to understanding their active, important position in world history. With Buddhism came the transmission of a complex visual milieu that continued to develop as it adapted to each cultural context, taking on its own political signifcance. In this overview, more than a millennium is painted with too broad a brush; the purpose of this study has been to trace these political patterns over time and space and across cultures while acknowledging there is still much more to say. Other examples abound, such as the monk-ruler Yeshé Ö (947–1024) of the kingdom of Gugé (996–1090) in post-imperial western Tibet, as well as Raven-Headed Mahākāla’s role in the founding narrative of Bhutan, to name just a couple.

A focus on religion’s relationship to power is but one way to understand Tibet’s historical and artistic place on the world stage; there are certainly others. It does effectively reveal a complex cultural negotiation, navigated by multiple stakeholders, where the arts played a key role and flourished, enriched on all sides by a creative dialogue between Tibetan, Tangut, Mongolian, Chinese, and Manchu traditions, negating any simplistic model of conflict and submission.

The objective here is not to suggest that the Mongolian, Chinese, or Manchu empires were idealized Buddhist kingdoms but rather that the deployment of religious rhetoric was central to their respective claims to legitimacy, with religious ritual being one of several means to establish and maintain power. This was not the only system employed by these regimes; their claims of universal rule ran parallel to other systems of political legitimation, such as the Confucian concept of the Mandate of Heaven. It was also not a cynical manipulation of religion. To limit motivations in the court patronage of Tibetan Buddhism to power politics is to limit our own view, as religious faith and political acumen are not mutually exclusive. Indeed, the Tibetan religiopolitical system at the center of this study depends on a belief in reincarnation and the efficacy of ritual magic. The modern Sino-Tibetan political situation is no longer governed by this system and is therefore an entirely different chapter in history. Nevertheless, a Chinese official’s recent suggestion that President Xi Jinping is considered a living Buddhist deity consciously draws on this past.[87]

1 See Sperling 2001b; Faure 2009, 93–99; Stiller 2018; FitzHerbert, forthcoming; Sinclair 2014; Dalton 2011; Jerryson and Juergensmeyer 2010; Farrer 2016. This chapter is largely drawn from my dissertation (Debreczeny 2007). Thanks to Gray Tuttle and Donald Lopez for their useful suggestions in refining this sprawling overview.

2 Samuel 2000 and 2002; and on the similar political role of Esoteric Buddhism in contemporaneous Tang China, see Goble 2016.

3 Beckwith 1987a; Dotson 2018; van Schaik 2015; Sørensen 2015.

4 Pelliot 1914; Sha Wutian 2013, 206–47, suggests Sogdian patronage of Cave 158 and a dating of about 839.

5 See also the Vimalakīrti-nirdeśa-sūtra painting in the British Museum (1919,0101,0.57).

6 Similar political messages can be seen in other Dunhuang wall paintings, such as the military procession in Cave 156, celebrating the local Chinese general Zhang Yichao’s expulsion of the Tibetan military governor in 848. Wang 2018, 122–38.

7 For example, Bhaiṣajyaguru, painted by the monk Palyang, dated 836 (British Museum, 1919,0101,0.32).

8 Kapstein (2004 and 2009) identifed Anxi Yulin Cave 25 as the Treaty-Edict Temple, but he has reconsidered this identifcation more recently (2014), nevertheless maintaining that they must be closely related, with Yulin Cave 25 being either a prototype or a copy of the temple described in the Treaty-Edict Temple document. I would suggest that both might relate to a series of such temples that ritually marked the inclusion of territory into the Tibetan Empire; Xie Jisheng and Huang Weizhong 2007; Sha Wutian 2013 and 2016; Wang 2018, 89–111. On dating issues of Yulin Cave 25, see Sha Wutian 2013, 355–82.

9 Kapstein 2009, 47.

10 Wang 2018, 89; Sha Wutian 2013, 470–92. See also Vairocana and the Eight Great Bodhisattvas in the British Museum (1919,0101,0.50).

11 Kapstein 2000, 65; Wang 2018, 51–121.

12 Kapstein 2000, 61–63.

13 Kapstein 2000, 60–61.

14 Kapstein 2000, 65, and 2009, 53.

15 Heller 1999, 37, 49, and 1994a.

16 Heller 1999, 49, 1994a and 1994b.

17 Heller 1997b: 385–90, Shawo Khacham 2015; Gugong bowuyuan 2006; Zhang Changhong, forthcoming.

18 van Schaik 2015, 67–68.

19 Beckwith 1987b, 3–11.

20 Dalton 2011, 126–43; Yamamoto 2012, 4–13.

21 van Schaik 2015, 66.

22 Samuel 2002, 7.

23 FitzHerbert, forthcoming.

24 Sørensen and Hazod 2007 37, 30–39.

25 Yamamoto 2015.

26 Jackson 1994, 63; Sørenson 2007, 38.

27 Sørensen and Hazod 2007, 36–39; Jackson 1994; Yamamoto 2012, 223–34; Martin 2001.

28 Roerich 1976, 479–80; Jackson 1994, 64; Yamamoto 2012, 76–77, 246–54.

29 Sørensen and Hazod 2007, 38; Yamamoto 2012, 226–30.

30 Sperling 1987 and 2004a; Davidson 2005, 334; Yamamoto 2012, 220–21. For his biography see Ldan ma ’jam dbyangs tshul khrims 1997b, vol. 2, 155.

31 Beckwith 1987b, 3–11.

32 These included Sakya, Tsurphu (Karma Kagyü), Tsal Gungthang, and Drigung monasteries, also later adopted by the various Mongolian khans and princes. See Sørensen and Hazod 2007, 367–76.

33 Atwood 2004b, 48.

34 For instance, an image in the beautiful kesi 缂丝 (cut silk) thangka of Acala was published as being from the Tangut Xia dynasty (1038–1227) in the groundbreaking exhibition When Silk Was Gold (Watt and Wardwell 1997, 92). The major Guggenheim Museum exhibition China 5,000 Years (Rodgers 1998, fig. 85) dated the same work as a Yuan thirteenth-to-fourteenth-century piece. For more Tibetological evidence on this kesi and a related portrait of Lama Shang, see Sørensen 2007, 353–80, who dates the original work to the early thirteenth century, about 1210. Broeskamp 2009; Henss 2014, fig. 292; and Noth 2015, 181, all argue for a fourteenth-century (Yuan) date. Gendun Tenpa (see chapter 5 of this volume) argues for an earlier Tangut origin, based in part on his identification of the patron as being from Tsongkha, which was absorbed into Xixia by this time. On this patron and dating about 1210, also see Sørensen 2007, 367–68.

35 Piotrovsky 1993, 168–69; Heller 2001, 221, 228; Elikhina 2015. This figure has been variously identified as Mahākāla, Vighnāntaka, Mahābala, and Acala. The Sanskrit mantra at top appears to be “Hum Chandra maharosana hum,” Acala’s mantra, confirming his identity. Thanks to Elena Pakhoutova for her reading of the Sanskrit.

36 Sperling 1994, 803–4n30, 819–20.

37 Sperling 1987, 1994, 2004a.

38 Sperling 1987, 31–50; Sperling 2004a, 10, 18.

39 Brook et al. 2018, 33.

40 Brook et al. 2018, 28, 42–43; Everding 2002; Sperling 1990b.

41 Sperling 1990b; Atwood 2004b, 50.

42 Sperling 1987, 37.

43 Hoog 2013, 328–37.

44 Jackson 2016, 155, 158, figs. 6.25 and 6.28.

45 It is unclear if this order was ever carried out. Atwood 2004b, 338–39.

46 Atwood 2004b, 50; Franke 1981, 310.

47 Wang Yao 1994; Charleux 2008; Debreczeny 2014.

48 Nian Chang, chap. 22; Shen Weirong 2004, 204; Franke 1984, 161–62.

49 For example, Nian Chang, chap. 22; Liu Guan’s (柳貫; 1270–1342) Huguosi beiming 護國寺碑銘 (“Temple for the Protection of the Nation Stele Inscription”), dated 1318; and the Rgya bod yig tshang, 287. See Franke 1984, 161–62, 175, 158; Sperling 1991; Shen Weirong 2004, 204.

50 Debreczeny, forthcoming; Stoddard 1985, 278; Beguin 1990, 52–56.

51 Debreczeny, forthcoming.

52 Nian Chang, chap. 22; Shen Weirong 2004, 204; Franke 1984, 161–62.

53 See Chen Yunru 2016; Watt 2010, 17–19, 226; Fu Shen 1990, 55–80. Sengge Ragi (Tib: Seng ge rab rgyas; Ch: Xiangelaji 祥哥剌吉; ca. 1283–1332) was sister of Külüg Khan (r. 1307–1311) and Buyantu Khan (r. 1311–1320). Her daughter Budashiri is depicted in the famous Metropolitan Museum of Art silk tapestry maṇḍala, dating around 1228–1229. See fig. 5.11 in this volume.

54 Franke 1996, 50n112. Other collaborative projects between Princess Sengge and Dampa are found in the petitions to grant amnesties for imprisoned officials as part of Buddhist observances. Franke 1996, 50, 62, citing the Yuanshi 26, 590.

55 For instance, Jing 1994 attributes to Anige the famous portraits of Qubilai and Chabi in the National Palace Museum, and Kossak 1998, 144–46, attributes the famous Green Tārā in the Cleveland Museum (1970.156), but both without clear evidence. On the continuing debate about various attributions to Anige, see Weldon 2010 and Henss 2011.

56 Karmay 1975, 20, pl. 11; Leidy 2008, 238; Watt 2010, 103, 106, fig. 137; Lee and Ho 1968, fig. 24.

57 While this is the only surviving complete example, this particular commission is not recorded. Watt and Wardwell 1997, 60–61, 95–99; Watt 2010, 110–14.

58 Atwood 2004b, 166, 608–9.

59 Linrothe 2009; Xie Jisheng 2014; Lai Tianbing 2015.

60 Chia 2016, 188–89; Huang 2014; Dunnell 2011; Khokhlov 2016.

61 Franke 1985; Chia 2016.

62 Chia 2016, 193; Huang 2014.

63 Chia 2016, 194. Therefore, the date of the colophon for the text also cannot be assumed to be that of the frontispiece; ibid. It has been suggested that the New York Public Library printings date to about 1850, but little evidence is provided for this dating. See Edgren 1993. Much of the early Ming Hongwu Southern Canon (ca. 1372–1403) was essentially facsimile recuts of the Qisha Canon, and copies of the Qisha Canon were still issued until the late sixteenth century. Chia 2016, 199, 206.

64 Tuttle 2011, 3–5; and Debreczeny 2011, 22–23.

65 These included the famous Ürgyenpa (1229/1230–1309). Bsod nams ’od zer 1976, 174; and Rta mgrin tshe dbang 1997, 242.

66 Farquhar 1978, 12; Bentor 1995, 31–54.

67 Robinson 2008 and 2016; Debreczeny 2016.

68 Robinson 2008, 405.

69 Sperling 2001a.

70 Elverskog 2006, 107–8, 111–12.

71 Rossabi 1995, 38–39; Wallace 2010, 92.

72 Ishihama Yumiko 2015; 2005; 1993, 38–56.

73 See Selig Brown 2004, 49, plate 15.

74 Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho, 1993. The first letter (pp. 91–93) is undated (ca. 1640s?), and a second letter (pp. 168–71) is dated to 1655.

75 Elverskog 2006.

76 Wu Hung 1995, 28; and Rawski and Rawson 2006, 248–51.

77 Wang Junzhong 2003, 80–134.

78 ’jam dpal rnon po mi’i rje bor/ rol pa’i bdag chen chos kyi rgyal/ rdo rje’i khri la zhabs brtan cing/ bzhed don lhun grub skal ba bzang/. Debreczeny 2011, 38–39.

79 Debreczeny 2011, 35, 57.

80 Debreczeny 2011, 35–36; Smith 1969b, 6; Uspensky 2002, 221, 225.

81 Hevia 1995; Uspensky 2002.

82 For a recent translation of his biography, see Bareja-Starzyńska 2015.

83 Bareja-Starzyńska 2015, 86; and Smith 1969b, 6, 76; Smith 2001b.

84 Among the specialists he brought back, one painter is mentioned but no sculptors. Bareja-Starzyńska 2015, 86, 122.

85 Atwood 2004b, 193–94; Bareja-Starzyńska 2015, 73.

86 Bĕlka 2003.

87 See “Xi Jinping’s Latest Tag: Living Buddhist Deity, Chinese Official Says,” Reuters, March 8, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-parliament-xiboddhisatva/xi-jinpings-latest-tag-living-buddhistdeity-chinese-ofcial-says-idUSKCN1GK0V6. This statement occurred at the same time term limits were removed, paving the way for Xi Jinping to serve as president for life.

Atwood, Christopher P. 2004b. “Validation by Holiness or Sovereignty: Religious Toleration as Political Theology in the Mongol World Empire of the Thirteenth Century.” The International History Review 26, no. 2: 237–56.

Bareja-Starzynska, Agata. 2015. The Biography of the First Khalkha Jetsundampa Zanabazar by Zaya Pandita Luvsanprinlei: Studies, Annotated Translation, Transliteration and Facsimile. Warsaw: Dom Wydawniczy ELIPSA.

Beckwith, Christopher. 1987a. The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese during the Early Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Béguin, Gilles. 1990. Art ésotérique de l’Himâlaya: Catalogue de la donation Lionel Fournier au Musée national des arts asiatiques. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux.

Bĕlka, Luboš. 2003. “The Myth of Shambhala: Visions, Visualizations, and the Myth’s Resurrection in the Twentieth Century in Buryatia.” Archiv Orientální 71, no. 3: 247–62.

Bentor, Yael. 1995. “In Praise of Stupas: The Tibet Eulogy at Chu-Yung-Kuan Reconsidered.” Indo-Iranian Journal 38: 31–54.

Broeskamp, Bernadette. “Dating the kesi-Tangka of Acala in the Tibet Museum, Lhasa.” 2009. In Xie Jisheng and Luo Wen Hua 2009, 185–97.

Brook, Timothy, Michael van Walt van Praag, and Miek Boltjes, eds. 2018. Sacred Mandates: Asian International Relations since Chinggis Khan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bsod nams ’od zer (13th cent.). 1976. Grub chen u rgyan pa’i rnam par thar pa byin brlabs kyi chu rgyun [Biography of Drupchen Ürgyen]. Gangtok: Sherab gyaltsan lama.

Charleux, Isabelle. 2008. “From the Yuan to the Qing Dynasty: The Career of a Famous Statue of Mahākāla, Lord of the Cemeteries.” In Han Zang Fojiao Meishu Yanjiu 漢藏佛教美術研究 A Journal for Sino-Tibetan Buddhist Art Studies, ed. Xie Jisheng 謝繼勝, 183–207. Beijing: Shoudu Shifan daxue chubanshe.

Chen Yunru 陳韻如, ed. 2016. Gongzhu de ya ji: Meng Yuan huangshi yu shuhua jian zang wenhua te zhan 公主 的雅集: 蒙元皇室與書畫鑑藏文化特展 [The Princess’s Collection: The Mongolian Royal Family and the Painting and Calligraphy Culture Exhibition]. Taipei: National Palace Museum.

Chia, Lucille. 2016. “The Life and Afterlife of Qisha Canon (Qishazang 磧砂藏).” In Spreading Buddha’s Word in East Asia: The Formation and Transformation of the Chinese Buddhist Canon, ed. Jiang Wu and Lucille Chia, 181–218. New York: Columbia University Press.

Dalton, Jacob. 2011. The Taming of the Demons: Violence and Liberation in Tibetan Buddhism. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Davidson, Ronald M. 2005. Tibetan Renaissance: Tantric Buddhism in the Rebirth of Tibetan Culture. New York: Columbia University.

Debreczeny, Karl. 2007. “Ethnicity and Esoteric Power: Negotiating the Sino-Tibetan Synthesis in Ming Buddhist Painting.” PhD diss., University of Chicago.

———. 2011. “Wutaishan: Pilgrimage to Five-Peak Mountain.” Journal of the International Association of Tibetan Studies 6 (Dec.): 1–133

———. 2014. “Imperial Interest Made Manifest: sGa A gnyan dam pa’s Mahākāla Protector Chapel of the Tre shod Maṇḍala Plain.” In Trails of the Tibetan Tradition: Papers for Elliot Sperling, ed. Roberto Vitali, 129–66. Dharamshala: Amnye Machen Institute.

———. 2016. “The Early Ming Imperial Atelier on the Tibetan Frontier.” In Clunas, Harrison-Hall, and Luk 2016, 152–62.

———. Forthcoming. “Patronage of the Musée Guimet Mahākāla Sculpture Dated 1292 Revisited.” In New Directions in the Study of Tibetan Buddhist Art History, ed. Zhang Changhong and Liao Yang. Cambridge: Harvard Yenching Institute.

Dotson, Brandon. 2018, “Cosmopolitanism and the Tibetan Empire.” Unpublished paper presented at Moving Borders—Tibet in Interaction with Its Neighbors, Symposium, Asia Society, NY, May 5.

Dunnell, Ruth. 2011. “Esoteric Buddhism Under the Xixia (1038–1227).” In Esoteric Buddhism and Tantras in East Asia, ed. Charles Orzech, Henrik Sørensen, and Richard K. Payne, 465–77. Leiden: Brill.

Edgren, Soren. 1993. “L. V. Gillis and the Spencer The Gest Library Journal, no. 2: 4–29.

Elikhina, Julia, ed. 2015. “Obitel’ miloserdiya”: iskusstvo tibetskogo buddizma katalog vystavk “Обитель милосердия”: искусство тибетского буддизма: каталог выставки [“Abode of Charity”: Tibetan Buddhist Art Exhibition Catalogue]. St. Petersburg: Gosudarstvennyĭ Ėrmitazh.

Elverskog, Johan. 2006. Our Great Qing: The Mongols, Buddhism and the State in Late Imperial China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Everding, Karl-Heinz. 2002. “The Mongol States and Their Struggle for Dominance Over Tibet in the 13th Century.”

Farquhar, David. 1978. “Emperor as Bodhisattva in the Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 38, no. 1: 5–34.

Farrer, D. S., ed. 2016. War Magic: Religion, Sorcery, and Performance. New York: Berghahn Books.

Faure, Bernard. 2009. Unmasking Buddhism. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

FitzHerbert, S. George. Forthcoming. “Rituals as War Propaganda in the Establishment of the Ganden Phodrang State.” In “The Ganden Phodrang Army and Buddhism,” Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie.

Franke, Herbert. 1981. “Tibetans in Yuan China.” In China Under Mongol Rule, ed. John D. Langlois Jr., 306–7. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

———. 1984. “Tan-pa, a Tibetan Lama at the Court of the Great Khans.” In Orientalia Venetiana I, ed. Merio Sabatini, 157–80. Florence: Leo S. Olschki.

———. 1985. “Sha-lo-pa (1259–1314), a Tangut Buddhist Monk in Yuan China.” In Religion und Philosophie in Ostasien, ed. Gert Naundorf, 201–22. Wurzburg: Konigshausen & Neumann.

———. 1996. Chinesischer und Tibetischer Buddhismus im China der Yuanzeit. Munich: Kommission für Zentralasiatische Studien, Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Fu, Shen C. Y. 1990. “Princess Sengge Ragi: Collector of Painting and Calligraphy.” In Flowering in the Shadows: Women in the History of Chinese and Japanese Painting, ed. Marsha Weidner, 55–80. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Goble, Geofrey C. 1987b. “The Tibetans in the Ordos and North China: Considerations on the Role of the Tibetan Empire in World History.” In Silver on Lapis: Tibetan Literary Culture and History, ed. Christopher Beckwith, 3–11. Bloomington: Tibet Society. Reprinted in Tuttle and Schaefer 2013, 133–41.

———. 2016. “The Politics of Esoteric Buddhism: Amoghavajra and the Tang State.” In Esoteric Buddhism in Mediaeval Maritime Asia: Networks of Masters, Texts, Icons, ed. Andrea Acri, 123–39. Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute.

Gugong bowuyuan 故宫博物院 and Sichuan sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiu yuan 四川省文物考古研究院. 2006. “Sichuan shiqu xian luo xu ‘zhao ala mu’ moya shike 四川石渠县洛须“照阿拉姆”摩崖石刻” [Sichuan Province Shiqu County Luoshou “zhao ala mu” Cliff Stone Carving]. Sichuan Wenwu 四川文物, no. 3: 26–30, 70–72.

Heller, Amy. 1994a. “Early Ninth Century Images of Vairocana from Eastern Tibet.” Orientations 25, no. 6: 74–79.

———. 1994b. “Ninth Century Buddhist Images Carved at lDan-ma-brag to Commemorate Tibeto-Chinese Negotiations.” In Tibetan Studies. Proceedings of the 6th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Fagernes 1992, ed. Per Kvaerne, 335–49, vol. 1 appendix, 12–19. Oslo: Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture.

———. 1997b. “Eighth- and Ninth-Century Temples and Rock Carvings of Eastern Tibet.” In Tibetan Art: Towards a Defnition of Style, ed. Jane Casey Singer and Philip Denwood, 86–103. London: Laurence King Publishing.

———. 1999. Tibetan Art: Tracing the Development of Spiritual Ideals. Milan: Jaca Book.

———. 2001. “On the Development of the Iconography of Acala and Vighnāntaka in Tibet.” In Embodying Wisdom: Art, Text and Interpretation in the History of Esoteric Buddhism, ed. Rob Linrothe and Henrik Sørensen, 209–28. Copenhagen: Seminar for East Asian Studies.

Henss, Michael. 2014. The Cultural Monuments of Tibet: The Central Regions. Munich: Prestel.

———. 2011. “Thirteenth or Eighteenth Century? A Response to David Weldon’s ‘On Recent Attributions to Aniko.’” AsianArt.com. Published February 14. http://www.asianart.com/articles/henss2/index.html.

Hevia, James L. 1995. Cherishing Men From Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and the Macartney Embassy of 1793. Durham: Duke University Press.

Hoog, Constance. 2013. “Lama Pakpa’s Elucidation of the Knowable.” In Schaefer, Kapstein, and Tuttle 2013, 328–37.

Huang, Shih-shan Susan. 2014. “Reassessing Printed Buddhist Frontispieces from Xi Xia.” Zhejiang University Journal of Art and Archaeology 浙江大學藝術與考古研究 1: 129–82.

Ishihama Yumiko. 2015. “The Dalai Lama as the cakravarti-rāja as Manifested by the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara.” Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 24: 169–88.

Jackson, David. 1994. Enlightenment by a Single Means. Vienna: Verlag der Osterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

———. 2016. A Revolutionary Artist of Tibet: Khyentse Chenmo of Gongkar. New York: Rubin Museum of Art.

Jerryson, Michael, and Mark Juergensmeyer, eds. 2010. Buddhist Warfare. New York: Oxford University Press.

Jing, Anning. 1994. “The Portraits of Khubilai Khan and Chabi by Anige (1245–1306), a Nepali Artist at the Yuan Court.” Artibus Asiae 54, no. 1/2: 40–86.

Kapstein, Matthew. 2000. The Tibetan Assimilation of Buddhism: Conversion, Contestation, and Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 2004. “The Treaty Temple of De-ga g.Yu-tshal: Identification and Iconography.” In Xizang kaogu yu yishu 西藏考古与艺术 [Essays on the International Conference on Tibetan Archaeology and Art], ed. Huo Wei 霍巍 and Li Yongxian 李永宪, 98–127. Chengdu: Sichuan chuban jituan and Sichuan renmin chubanshe.

———. 2009. “The Treaty Temple of the Turquoise Grove.” In Buddhism Between Tibet and China, ed. Matthew Kapstein, 21–73. Boston: Wisdom Publications.

Karmay, Heather. 1975. Early Sino-Tibetan Art. Warminster: Aris & Phillips.

Khokhlov, Yury. 2016. “The Xi Xia Legacy in Sino-Tibetan Art of the Yuan Dynasty.” Asianart.com. Published September 15. http://www.asianart.com/articles/xi-xia.

Kossak, Steven M., and Jane Casey Singer. 1998. Sacred Visions: Early Paintings from Central Tibet. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Lai Tianbing. Han Zang Gui Bao (“Treasures of Sino-Tibetan art: A Study on the Sculptures at Feilaifeng in Hangzhou”). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, 2015.

Lee, Sherman E., and Wai-Kam Ho. 1968. Chinese Art Under the Mongols: The Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368). Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art.

Leidy, Denise Patry. 2008. The Art of Buddhism: An Introduction to Its History and Meaning. Boston: Shambhala.

Linrothe, Rob. 2009. “The Commissioner’s Commissions: Late Thirteenth Century Tibetan and Chinese Buddhist Art in Hangzhou Under the Mongols.” In Buddhism Between China and Tibet, ed. Matthew Kapstein, 73–96. Boston: Wisdom Books.

Martin, Dan. 2001. “Meditation in Action: On Zhang Rinpoche, a Meditation-Based Activist in Twelfth-Century Tibet.” Lungta 14 (Spring): 45–56.