asianart.com | articles

Articles by Jean-Luc Estournel

Download the PDF version of this article

September 29, 2020

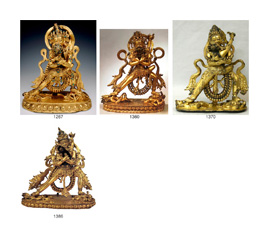

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

Since the end of the 1960s, public and private collections around the world have housed an important group of Tibetan objects with a very strong typological, iconographic and stylistic unity, constituting a particular group among all those recorded to come from the “land of snows”.

Fig. 1

In 1993, I was given for the first time the opportunity to lay the foundations for the association of this style with the photographs taken at Densatil (gdan sa mthil) by P.F. Mele during the expedition led by Professor Giuseppe Tucci of the Italian ISMEO in 1948. Rapidly written for the needs of an auction catalogue from the few sources then available, this text quickly proved to be incomplete and erroneous on certain points, but it was the starting point of the "Densatil Project" which aims to collect all the photographs, publications and information available since then.

Densatil monastery, the origins of which can be traced to ca. 1198, was perhaps first founded by the monk Dorje Gyalpo (rdo rje rgyal po) who, nearly half a decade ealier in 1158, had settled the area of Phagmodru (phag mo gru).

It is famous for its eighteen stupas housing the relics of the lineage of eighteen successive abbots once built in the main hall (gtsug lag khang), and more particularly the eight tashi gomang stupas (bkhra shis sgo mang) partially visible on the few 1948 photographs. (Fig. 1)

After the fire and the complete blasting of the monastery in the 1960s, many fragments of Densatil's treasures were scattered in various public and private collections around the world, as well as in various other Tibetan monasteries, at Lhasa (Potala and Jokhang), in Drigung ('bri gung) , Samye (bsam yas) or Reting (rwa sgreng) among others. This last point demonstrates that it is necessary today to avoid taking into account the present location of an object in Tibet as an indication of its provenance from that same place.

Among the objects that escaped being sent to smelters to recover the copper, some reached us after being burned to remove their original gilding. The semi-precious stones with which they were inlaid have also often been removed. The numerous fractures to the various parts of their bodies are the result of the dynamiting that caused the collapse of the tashi gomang stupas on themselves and under the walls and upper floors of the shrine.

The details of the history of Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa and the Lang (rlangs) clan who ruled Tibet from the palace of Neudongtse (sne'u-gdong-rtse) during the 14th and 15th centuries as the Phagmo Drupa dynasty and whose members succeeded one another on the abbot’s throne of Densatil are well known today and have been the subject of an important and remarkable study by Olaf Czaja [1].

The exhibition at the Asia Society in New York in 2014 [2] revealed to the general public the history, and the artistic richness of this high place of history and spirituality, without however really attempting a real approach from an art history perspective.

The development of the "Densatil Project" now makes it possible to draw up a chronology of the famous eighteen stupas, in the light of history, photographs from 1948, and hundreds of listed objects coming from the eight tashi gomang stupas ornamentation.

The classification of the numerous objects from the eight tashi gomang stupas according to stylistic and iconographic elements and the analysis of the treatment of details such as jewellery and lotus pedestals has made it possible to highlight eight globally homogenous groups that should therefore in principle correspond to the eight tashi gomang stupas and to make it possible today to try to propose attributions of a certain number of these objects to their original stupas.

Fig. 2For ease of reading by non-specialists, as the names of tibetan characters and places are complex, all those mentioned several times in the text have been transcribed here according to a simplified phonetic system. Those appearing only once have been left in classical transliteration. Moreover, in the majority of cases, only the Sanskrit names of the deities have been retained and also transcribed according to the most common simplified phonetic system.

Of Densatil's eighteen stupas, we can so far only be certain of the form of thirteen.

A first group is composed of five large stupas, belonging to the ancient typology known as the “mahāparinirvāṇa stupa” in memory of the mahaparinirvaṇa of the Buddha in Kuśīnagar which is known in Tibet as bka ‘gdams mchod rten by association with the Kadampa school and the person of its founder, the Indian master Atisha (982-1054). (Fig. 2)

Fig. 3

This archetype was very common in Tibet between the 12th and 15th centuries, a period during which many specimens were made in sizes ranging from a few centimeters to more than three meters high. For example, the one that would have housed the relics of Naropa (1016-1100) (na ro pa gdung rten) at Nyethang (snye thang) monastery would have measured 3 meters and 22 centimeters high [3]. Shakabpa evokes this tradition which would have been introduced in Tibet by Atisha. [4] The omnipresence of this stupa associated with the multiple portraits of Atisha clearly indicates the importance of this symbol in his tradition and spiritual lineage. (Fig.3)

According to Shakabpa [4], Spyan snga tshul khrims 'bar (1033/8-1103) would have built a stupa decorated with jewels on this model. It could be a stupa that he had built for his master 'Brom ston (1004-1064), himself a direct disciple of Atisha, in his monastery of Lo at Taktse (stag rtse) in northeast Lhasa.[5] Shakabpa also indicates that many nepalese and tibetan craftsmen are said to have made a very large number of them out of metal alloys.

Fig. 4

A second larger group consists of the eight most remarkable and monumental ones, falling under the category of “Bahudvara stūpa” commemorating the first sermon of the Buddha at Sarnath, which is known in Tibet as gomang (sgo mang) or tashi gomang (bkhra shis sgo mang).

In the Tibetan world, the gomang generally takes the form of a stepped base most often with stepped edges on which are signified symbolic doors or chapels housing deities, supporting the classical stupa dome surmounted by its parasols. There is a great variety of them, of all sizes and in all possible materials.

The very large stupas with multiple interior chapels that flourished in the 14th and 15th centuries throughout Tibet such as those of Gyantse (rgyal rtse), Narthang (snar thang), Jonang (jo nang), Jampaling (byams pa gling) or Gyang, more commonly known under the generic name of Kubum (sku 'bum) are the most monumental examples of existing tashi gomang. The two terms can be considered synonymous.

The building of a tashi gomang to house the relics of a great master is attested very early in the Tibetan tradition. One of the oldest of which it is possible to find the trace was probably the earthen one having sheltered part of the relics of Atisha built shortly after 1054 in the sku 'bum lha khang of Nyetang (snye thang) photographed by Charles Bell in the 1920s. [6] (Fig.4)

Fig. 5

The oldest richly ornamented tashi gomang of which we can be aware is undoubtedly the one most probably erected during the last quarter of the 11th century for the relics of Rkyang pa chos blo of rgyang ro spe'u dmar studied and photographed by Professor Tucci in the 1930s in Samada (khyang phu). Rgyang ro spe'u dmar would be the ancient name of the shrine [7] and Rkyang pa chos blo its founder. The photographs show us beside a huge Kadampa type stupa, a several meters high tashi gomang structured in several decreasing levels supporting a form of mahaparinirvaṇa stupa. (Fig. 5) The rich decoration developed on the whole surface in "gilded bronze" with figures under arks supported by small pillars. It restores a Vajradhatu mandala with its thirty-seven main deities. It is known that Rkyang pa chos blo received the initiation to this cycle directly from Rinchen Zangpo (rin chen bzang po) (958-1055) [8] who was himself a disciple of Atisha.

The Blue Annals tells us that at the end of the eleventh century, part of Marpa's relics (mar pa lo tsa' ba chos kyi blo gros – 1012-1097) were placed inside a tashi gomang made of acacia wood that his son lost in gambling. The relics were then removed and placed in a square box [9]. A tashi gomang is also thought to have been erected in Ralung (rva lung) between 1216 and 1225 to house the relics of Tsangpa Gyare (gtsang pa rgya ras) (1161-1211) [10] but apart from the fact that artists may have been involved in its ornamentation, no precise description of its iconographic structure has come down to us. In 1153, a golden tashi gomang was erected by Sgom pa tshul khrims snying po (1116–1169) to house the heart of Gampopa (sgam po pa) (1079-1153) [11]. Once again, no description is known, and it is therefore impossible to extrapolate on its precise structure.

Shakabpa speaks at the same time of tashi gomang stupas and of multi storied Kadampa tombs. He also evokes gold and silver tashi gomang in Narthang, Drigung and Densatil. [12]

It is therefore clear that the term tashi gomang can refer to a number of variations of the same archetype, with different sizes, materials or exterior finishes and iconographic program. Consequently, the mention of the creation of a tashi gomang without further details in a historical account does not systematically induce, even in the Drigungpa or Phagmodrupa specific context which will be the one that will interest us here, that it is an example of the same typology as those photographed in 1948 in the main hall of Densatil.

What remains is a group of five stupas for which little information has reached us, but which have had to take on different forms.

If this group of eighteen stupas recorded at the beginning of the 20th century [13] corresponds to a lineage of the first eighteen abbots of the monastery, its chronological sequence takes place over a period of four hundred years, between the death of Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa in 1170 and that of Dragpa Jungne (Grags pa ’byung gnas -1508 –1570).

We will therefore try here to restore this chronology by attributing to each abbot the stupa that must have been his, and to each stupa, its shape, its potential decoration and, when possible, the sculptures that must have been placed in it.

Twelfth century stupas

Abbot 1 / Stupa 1. Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa (rdo rje rgyal po phag mo gru pa) (1110-1170)

Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa was the founder of the future monastery, which during his lifetime consisted only of a group of huts. He managed to make the community prosper by receiving gifts and offerings, sometimes from very far away.

When he died in 1170, his heart which had remained intact after the cremation was placed in a stupa called tashi wobar (bkra shis 'od 'bar), which means "Radiating Light of Auspiciousness"[14]. It was a large mahaparinirvaṇa stupa of the Kadampa type mentioned above, as was common practice at the time. The representations of the sun and the moon at the top would have been made of gold, or at least gold-plated.[15] According to multiple concordant sources, Taklung Tangpa Tashi Pel (Stag lung thang pa bkra shis dpal) (1142-1209/10) paid for this stupa while Jigten Gonpo ('Jig rten mgon po) (1143-1217) sent Mgar dam-pa cho sdings pa to Nepal to commission a golden copper parasol to shelter it.[16]

Fig. 6

Despite of this installation in a hut, the disciples did not agree to build a real sanctuary on the spot. It was only in 1198, after a long debate between Jigten Gonpo and Taklung Tangpa Tashi Pel, that it was finally decided to build a shrine around the original hut of their master. From then on, the tashi wobar, the first of the series of eighteen commemorative stupas, was housed inside the tsuglagkhang (gtsug lag khang), along with the hut and the first treasures of the community. In 1948, it stood with four other stupas of the same type and size on a tiered altar in the center of the east wall of the tsuglagkhang. Unfortunately, only the third, fourth and fifth are visible, textile wrapped on the famous photograph by P.F. Mele. (Fig.6)

An attempt to estimate the height of these five stupas suggests that each may have been about 1.8 to 2 meters high. It is interesting and unusual to note in the photographs that all five of them, as well as those that made up the final piece of the tashi gomang stupas, are wrapped in protective textiles and that only their tops decorated with the scarf, lotus button, lunar and solar symbols and a triple jewel remain visible and appear extremely shiny and well-kept. This could confirm that these final parts may indeed have been gilded or made of gold. The recurrent mention by Densatil's visitors of the existence of gold and silver stupas could be a clue to the fact that these Kadampa-type stupas may have been made of silver. This could explain why, while many of objects from Densatil are known today, none of these stupas have been found, even in a fragmentary state.

In the years following the construction of the monastery, this tashi wobar, was to be at the heart of an incredible political and artistic adventure due to Jigten Gonpo.

Thirteenth Century Stupas

Abbot 2 / Stupa 2. Jigten Gonpo (’jig rten mgon po) (1143-1217)

Fig. 7

Jigten Gonpo served as second abbot of Densatil from 1177 to 1179 before leaving to develop his own monastery in Drigung (‘bri gung mthil).

Watching over the maintenance of their master's monastery from afar, Jigten Gonpo and Taklung Tangpa Tashi Pel, the main disciples of Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa, left the monastery without an abbot for twenty-nine years, until 1208.

After the construction of the main hall of Densatil in 1198, Jigten Gonpo went to meditate at Gampo (sgam-po) in Dagpo (dvags po), and there had a vision of the "pure crystal mountain" of Tsāri with Chakrasamvara ('khor lo bde mchog) in his palace, the whole surrounded by 2800 deities, organized like a monumental tashi gomang. This vision of Chakrasamvara in a tashi gomang was perpetuated in a simplified manner on numerous thangkas illustrating the Tsāri pilgrimage on which the stupa takes the more classical Tibetan form, simply covered with small painted doors. (Fig.7).

On the other hand, the large number of paintings associated with the monasteries of Drigung and Taklung depicting Chakrasamvara, sometimes between the Jigten Gompo’s or Taklung Tangpa Tashi Pel footprints [17] highlights the importance of this deity for the disciples of Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa and illuminates the deep meaning of Jigten Gonpo's vision.

Back in Drigung, he decided to build the monument he had visualized, in memory of his master Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa. The construction of this tashi gomang seems to be the result of the work of two main protagonists, Tshul khrims rin chen who would have been in charge of the structure, and a Nepalese artist named Manibhadra specialized in decoration and ornamentation in precious material.[18] Despite a 1202, provisional consecration made by Jigten Gonpo, who thought to die soon, the construction work seems to have lasted until 1208.[19] We do not know much about this construction except that it would have been erected first of all in wood, then in precious materials. [20] This last information confirms the intervention of the two personalities mentioned above.

We have seen above that the design of a tashi gomang structured in tiers, decorated with chapels housing deities and surmounted by a mahaparinirvaṇa stupa is attested in Tibet at least since the eleventh century. Jigten Gonpo cannot be regarded as a true innovator in this respect. The particularity of his monument was to be found not in its form, but in the iconographic program designed to cover it.

The iconographic scheme of the monument resulting from Jigten Gonpo's vision has come down to us in some texts that have been widely studied by Olaf Czaja and Christian Luczanits ([21].

These works present some variants among themselves, thus demonstrating that they do not all describe exactly the same monument or reproduce exactly the same original text. Relying on serious iconographic arguments linked to the appearance and diffusion of the initiatory cycles, which it would take too long to repeat here, Christian Luczanits comes to the conclusion that these texts can in no way be contemporary with Jigten Gonpo as Olaf Czaja thinks, but at least a century later. He hypothesizes that these descriptions may in fact be inspired by one of Densatil's tashi gomang. In the latter case, the concordance of an announced number of 2,800 figures could suggest that this model could be the first Densatil tashi gomang erected from 1267 for Dragpa Tsondru. (Grags pa brtson 'grus)

Fig. 8

It is therefore clear that this literary description of the tashi gomang visualized by Jigten Gonpo is most likely slightly different from the original. We must also take into account the fact that Densatil's monuments counted a very variable number of deities and agree that the text considered as initial should only be considered as a basic grid that may have known slight variations on each monument. These variations are probably related to the initiatory cycles associated with each of the abbots for whom the stupas were intended.

Our purpose here will not be to go once more into all these structural and iconographic details, but simply to use them to locate the places where the sculptures we will be talking about should have been.

We will here simply refer to the 6-tiers structure (Fig.8) corresponding respectively from top to bottom:

- At the top, Tier 1, around a huge Kadampa style mahaparinirvaṇa stupa, are arranged in masters lineages. The text chosen by Olaf Czaja associates a representation of Vajradhara in the centre of each face of the stupa. The one studied by Christian Luczanits favours, for clearly stated iconographic reasons, two representations of Vajradhara to the east and south, Chakrasamavara to the west and Hevajra to the north. The simple examination of P.F. Mele's photographs showing the presence of a representation of Chakrasamavara at the top of a tashi gomang leads us to consider the text chosen by Christian Luczanits as probably more precise. Three aspects of Vajrayogini/Vajravarahi are indicated to be placed in front of each of these four main deities. It is interesting to note that on the south side of this Level 1, we find at the foot of the Kadampa type stupa, a representation of Atisha founder of the Kadampa school among Tilopa, Naropa, Marpa, Milarepa, and Gampopa. This probably should be seen as an expression of the old and strong connection which will be maintained throughout history between the Phagmo Drupa abbots and those of the Kadampa school even after the reform of the latter by Tsongkhapa and until the reunification of Tibet by the 5th Dalai Lama.

- Tier 2 presents various cycles of Anuttarayoga Tantra including the 72 deities mandala of Guhyasamaja in the east, the assembly of Vajrakila in the south, that of Hevajra in the west, and the 62 deities mandala of Chakrasamvara in the north. An aspect of Avalokiteshvara is arranged at each of the four corners.

- Tier 3 presents on the east face the Vajradhatumandala in 47 deities, on the south, the assembly of Buddhakapala, on the west, the assembly of Prajnaparamita and on the north, the mandala in 14 deities of Chakrasamvara. An aspect of Acala is arranged at each of the four corners.

- Tier 4 presents in the center of each side a Buddha surrounded by two of the eight Bodhisattvas of the bhadrakalpa and two wrathful deities on each side. They are surrounded on each side by 250 representations of the Tathagata of their respective direction. A dvarapala is arranged at each of the four corners.

- Tier 5 is dedicated to goddesses. On each side are three central goddesses flanked by the group of the sixteen goddesses of sensual enjoyment bearing offerings. The four main goddesses occupying the center of each side are Parnashavari in the east, Eight armed Tara in the south, Dhvajagrakeyura in the west and Vasudhara in the north.

- Tier 6 is the lowest level. On each face, on either side of a central lotus stem, we find an aspect of Mahakala and one of the goddess Lhamo, themselves flanked by two deities of wealth and two nagarajas closing the section. They are all arranged in the foliage of scrolls supporting the lotus flower from which the rest of the monument seems to emerge.To sum up, the tashi gomang model created by Jigten Gonpo must be considered, as described by Christian Luczanits in the title of his article, as a "mandala of mandalas", a veritable tangle of universes of deities (2800 in total), referring perfectly to Professor Tucci's description during his visit to Densatil in 1948, "The whole Olympus of Mahayana seemed to have been assembled on those monuments". [22]

This particular type of tashi gomang which must be considered as the "Reliquary Stupa of Many Auspicious Doors for Phagmo Drupa" will then be declined to commemorate some deceased abbots of Drigung and Densatil since they were the depositories of the direct lineage of the master. While very little is known about the possible tashi gomang erected in Drigung after that of Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa, the analysis of those of Densatil allows us to note that if the general iconographic plan has globally remained the same over time, variations have been made on some of them. The numbers of divinities indicated by the texts in fact imply that some mandalas constituting certain tiers have been modified or replaced by more complex ones, while perhaps retaining the same basic divinities. These variations are probably due to the particular cycles studied by the concerned abbots.

Being large mandalas, the convention is that the face of the tashi gomang stupas exposed to the viewer should always be the eastern face, even if this does not correspond to the actual geographical orientation. As a result, P.F. Mele's photographs essentially show us the eastern face of the monuments. The south side should therefore be considered to be on the visitor's left, the west on the back, generally facing the wall, and the north on the viewer's right.

The fact that Jigten Gonpo chose to build this memorial stupa to his master in his own monastery rather than in Densatil, which would have been his logical location, is historically interesting. Indeed, it may suggest that the abbot of Drigung may have attempted to shift the power of Densatil's spiritual center from its abandoned location to his own monastery, to gain political advantage over other powerful contemporary buddhist schools.

This became obvious when, in 1208, he tried to empty Densatil of his sacred substance by sending the library to Gampo, supposedly to fulfil his master's wish, and above all by transferring the commemorative stupa tashi wobar containing the heart of Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa to Drigung in order to place it at the top of the complex structure he had built for this purpose and thus complete his Tashi gomang. [23]

What appeared to be a looting of the monastery of Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa did not fail to provoke a local revolt. To calm the spirits, Jigten Gonpo decided to return the tashi wobar stupa to Densatil with Dragpa Jungne (grags-pa 'byung-gnas -1175-1255), one of his main disciples as abbot. The latter belonged to the Lang (rlangs) clan, a powerful local family. He had to offer many gifts to the local nobility to calm the spirits.

Once the tashi wobar stupa returned to Densatil, Jigten Gonpo made a replica filled with other relics of his master to restore its greatness to his tashi gomang in Drigung.

Fig. 9

Apart from the iconographic scheme of 2,800 deities that covered it, we know nothing specific about this commemorative tashi gomang for Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa in Drigung. This is mainly because the monastery was completely destroyed by the Mongols and the Sakyapa in 1290.

In 1948, P.F. Mele photographed in Tsetang (rtse thang) a gilt copper plate depicting offering goddesses made in a 13th century characteristic style. (Fig.9) The shape and iconography of this object is characteristic of a tashi gomang for Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa decoration.

Considering first that Tsetang was only built in 1351, preventing de facto the object from being considered as originating in it, and secondly that only the Drigung or Densatil monasteries were able to build a tashi gomang of this particular typology during the thirteenth century, it is conceivable that this plate could be a survivor from the Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa's Tashigomang in Drigung preserved there after de complete destruction of the monastery as a sufficiently important relic to be exhibited and shown to Professor Tucci, who unfortunately has not published any note on the subject. [24]

When Jigten Gonpo died in 1217, a tashi gomang, possibly close to the one he had created for Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa, is reported to have been built for him in Drigung and a large commemorative stupa of the same shape and size as the tashi wobar called bkra-shis kun-tu 'od, was erected at Densatil, also with the sun and moon in gold or gold plated.[25] In 1948, it stood textile wrapped with four other stupas of the same type and size on a tiered altar in the center of the east wall of the tsuglagkhang. Only the third, fourth and fifth are unfortunately visible in the famous photograph by P.F. Mele.

Abbot 3 / Stupa 3. Dragpa Jungne (Grags pa ‘byung gnas) (1175-1255)

Sent to Densatil by Jigten Gonpo, Dragpa Jungne occupied the abbot throne from 1208 to 1235 before leaving to ascend the temporarily vacant throne of Drigung from 1235 to 1255. This period is an important turning point in the history of Tibet which then had to face the Mongol invasions. The main Buddhist schools competed for the graces of the invaders and for local political advantage. The advantage was taken from 1244 onwards by the Khön clan who held the great monastery of Sakya.

Before leaving for Drigung in 1235, Dragpa Jungne took care to place his brother Dragpa Tsondru (Grags pa brtson 'grus - 1203-1267) on Densatil's throne, thus initiating a shift of dependence, which took Densatil from the tutelage of Drigung to that of his clan, the Lang.

Fig. 10

As abbot of Drigung, he would have been behind the building of two tashi gomang (probably for his two predecessors and direct successors of Jigten Gompo) and would have asked that another be built for him as well. [26] The mention of gemstone decoration unfortunately does not inform us about the exact structure of these tashi gomang stupas, namely whether they followed the archetype of the monument for Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa created by Jigten Gonpo with many cast figures or had a less developed votive character, perhaps more in line with the cost of such monuments in a complicated and financially less prosperous period than a few years earlier. Again, we will never know anything precise about these three Tashi Gomang of Drigung mainly because the monastery was destroyed by the Mongols and the Sakyapa in 1290.

At his death in 1255, his brother Dragpa Tsondru (grags pa brtson ‘grus) ordered for him a large commemorative stupa placed in Densatil in the same shape and size as the Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa's tashi wobar, called bkra shis 'od dpag.[27]

In 1948, it was placed, textile wrapped, with four other stupas of identical type and size on a tiered altar in the center of the east wall of the tsuglagkhang. It can be seen partially on the famous photograph by P.F Mele. (Fig.10)Abbot 4 / Stupa 4 / tashi Gomang 1- Dragpa Tsondru (Grags pa brtson ’grus) (1203-1267)

Brother of Dragpa Jungne, Dragpa Tsondru ascended the throne of Densatil in 1255. The extent of his fame brought him many offerings from as far away as the Khasa Malla kingdom or present-day Sri Lanka. The Mongolian takeover of Tibet then placed Densatil and his region under the protection of Prince Hülegü Khan (1217-1265), grandson of Genghis Khan and brother of Kublai, who governed the areas that make up present-day Iran and Iraq.[28] The prince is said to have made important offerings to the monastery on three occasions, among them the famous six golden pillar ornaments that would have adorned the surroundings of the first tashi gomang erected in Densatil from 1267 for Dragpa Tsondru.[29]

Fig. 11

Apart from differing information on the dimensions of these six pillar ornaments we know nothing about their shape or decoration. Olaf Czaja suggests that one of them can be seen in a photograph by P.F. Mele hanging from a large pillar separating a tashi gomang from the altar supporting the five large kadampa-style stupas and the sculptures of the spiritual lineage of the abbots of Densatil. This proposal is unfortunately impossible to hold for two reasons. The first is that if these ornaments were indeed arranged around the first tashi gomang erected in Densatil in 1267 for Dragpa Tsondru, the monument visible in the photograph can in no way be identified as that of the fourth abbot of the place since it is stylistically attributable to the fourteenth century and not to the thirteenth. The second reason is that one only has to look at the photograph carefully to see that it is in no way a pillar ornament, but simply the Prabhāmaṇḍala to which the sculpture hanging from this same pillar is leaning. (Fig.11)

The realization of this first tashi gomang, probably following the model of the one erected in Drigung for Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa since it would also have been composed of 2,800 deities, is situated at a key moment in the history of the Lang / Phagmo Drupa clan.

In fact, with the definitive seizure of power over Tibet by the Sakyapa through the nomination of Phagpa (‘Phags pa - 1234-1280) by Kublai as viceroy of Tibet, the Sakyapa administration divided the territory into 13 myriarchies, one of which fell to the Lang, already strong with the prestige of their monastery of Densatil. To further assert their power, they erected the fortress of Neudongtse, which became the political seat of their dynasty.

It is conceivable that at that time the Lang clan, thanks to the wealth poured into the monastery by Hülegü Khan and other generous donors, was in a prosperous financial position to decide to undertake this exceptional construction in order to affirm the greatness of its temporal and spiritual power over the myriarchy and beyond.

Before considering what this first tashi gomang to Densatil might have looked like, it is essential to set out a number of points relating to the methodology used in the attempt to analyse the eight tashi gomang stupas that will follow.

In order to propose a reconstruction of the decoration of each of Densatil's eight tashi gomang stupas, we will use all the objects that can be considered stylistically and iconographically coming from them. At this stage, it is interesting to note that this large group of objects can precisely be divided into eight globally coherent sets highlighting a logical stylistic chronology.

Within each of these eight groups, it is interesting to note that beyond an overall stylistic unity essentially marked by the treatment of costumes, jewellery and ornaments, it is clear that for each of the eight tashi gomang stupas, several artists or workshops, each bringing its own particularities, had to work either simultaneously or successively on the construction of these monuments. It is conceivable that these various workshops have in fact worked for different sponsors, all anxious to acquire merits by offering sculptures for the ornamentation of tashi gomang stupas.

It also appears that the proximity of a tashi gomang with each other allowed artists to look at what their predecessors had achieved and to be inspired by it. This last remark explains why it is sometimes delicate, without having an object in hand, to attribute it to one tashi gomang rather than another, especially if they were built at very short intervals, making it possible to envisage that the same artists worked on them.

Another difficulty encountered for a precise positioning of each deity in the place that should originally have been his, is the fact that we are often faced with ancient iconography and little known aspects of certain deities, and that in the chaos that must have presided over the destruction of Densatil their attributes were often broken, making their exact identification even more delicate.

Last point, Densatil having housed thousands of sacred objects in addition to those that adorned the eight Tashi gomang stupas, objects probably often made by the same artists, it must be integrated that many of these works may not come from these eight great stupas. Thus, for example, the excessive number of Nagarajas, long considered as all coming from the tashi gomang stupas, is probably explained by the fact that they must have come from the bases of certain sculptures or altars that they were supposed to give the impression of supporting. It is also possible that many of them may have come from other shrines.

For each tashi gomang, we will approach the study, first of all by the figures of the four Guardian Kings (Lokapalas), which constitute a very interesting and significant group in the reconstruction of the stylistic and chronological evolution of the eight monuments. Each tashi gomang will then be considered level by level.

Fig. 12

Tibetan texts describe the tashi gomang visualized by Jigten Gonpo for Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa from the top (tier 1) to the bottom (tier 6). This is due to the descriptive logic of a huge mandala of mandalas that must start from the center which is necessarily at the top in a three-dimensional projection.

We prefer here to consider the study from the bottom to top, following the logical order of construction. Considering that the construction of a tashi gomang may have lasted many months, or even a few years, this will sometimes allow us to better understand the chronology of each one and the stylistic transitions from one to another.

It should be pointed out here that comparisons with P.F. Mele's photographs must take into account the fact that the majority of them were taken with wide-angle lenses, which strech the figures and monuments, and sometimes gives us a distorted view of them.

Apart from the fact that it should have been adorned with 2,800 figures like the one erected in Drigung for Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa, no more precise information has been received about this monument. We will therefore try to reconstruct what it is possible to envisage from the elements which, for logical and stylistic reasons, cannot integrate any of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries tashi gomang stupas.

Fig. 13

Among P.F. Mele's photographs, one showing us the Nagaraja Ananta, Vaishravana and an aspect of Mahakala could for various reasons be considered as the only photograph of this first tashi gomang in Densatil. (Fig.12). However, it cannot be totally excluded that this may be a detail of the eighth and final of these tashi gomang stupas. Nevertheless, one of the overall photographs of the monument, which for technical and stylistic reasons can only be considered as the eighth of these tashi gomang stupas, shows a wooden balustrade positioned very close to the large double lotus supporting the monument. (Fig.13) The positioning of this barrier, whose shadows can be seen on the petals of the great lotus, makes it difficult to imagine that the photograph showing us the three deities could have been taken behind it with so much space and light. On the other hand, another slightly blurred photograph taken from above partially shows the tops of the lotus petals, which appear to be more rounded and less pointed than what can be seen in the upper right corner of Figure 12.

In any case, we will see further on that these first and eighth tashi gomang stupas were probably arranged side by side and that the first seems to have in some ways considerably influenced the artists who worked on the last one.

This first representation of a Nagaraja supporting a lotus pedestal placed next to protective deities in loops of lotus scrolls following Jigten Gonpo's vision for the tashi gomang of Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa directly inspired by Indian archetypes of the Indian Pala period, refers to certain thangkas of the same time.

Fig. 14

Many of these paintings are clearly associated with the lineage of Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa and Jigten Gonpo. They are a good demonstration of artistic and aesthetic unity between the pictorial and sculptural works.

One of the best example is undoubtedly a remarkable portrait of a lama preserved in the Pritzker collection (Fig.14). In the lower register we see protective deities surrounded by lotus scrolls among which we find Vaishravana, Mahakala, Lhamo and Nagarajas supporting the throne alike they are found around the bases of tashi gomang stupas of the type we are interested in here.

It is therefore obvious that in the artistic movement developed around the visions of Jigten Gonpo, the same spectacular and extremely precious character was used to magnify the memory of the succession of masters of the spiritual lineage. We will again note the presence of Atisha in this lineage.

The precise identity of the abbot at the center of this remarkable painting, which can only come from a major sanctuary in view of its quality of execution, is not specified by any inscription.

Insofar as the Marpa, Milarepa, Gampopa, Phagmo Drupa and Jigten Gonpo lineage is perfectly identifiable in the upper register, the latter being represented in a larger size in the center, it is highly probable that this is one of his direct successors. Thus, if we consider this painting as coming from Drigung, only three abbots after him were his direct disciples, Tshul-khrims rdo-rje (1154-1221), Bsod-nams Grags-pa (1187-1235) and Dragpa Jungne (1175-1255). In a logic associated with Densatil, it could only once again be Dragpa Jungne (1175-1255).

Returning to the tashi gomang for Dragpa Tsondru, it should have housed all the sculptures attributable to a tashi gomang from an iconographic point of view and stylistically datable from the 13th century since, as we shall see later, there has been no other tashi gomang of the Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa type, built in Densatil before 1360.

Another hypothesis could be that this important group could come from one of Drigung's tashi gomang stupas. However, as Drigung was destroyed and burnt down in 1290, it is unlikely that such a group survived the sack of the monastery and remained grouped in such a relatively good state of conservation for seven centuries. The very high probability that these works come from Densatil itself is reinforced by the fact that Chinese scholars have found some of them in the ruins of Densatil.

The analysis of these sculptures reveals that different sculptors' workshops must have worked on the construction of this monument. This multiplicity of artists having worked successively or concomitantly seems logical if we consider that, as the texts report, each tashi gomang was made over periods of several months or even several years. An attempt to place each of the objects in the place normally assigned to it reveals that the two most active workshop seem to have generally worked one on the lower part and the other on the upper part. This is probably a confirmation of the chronology of the work. The consistency of this set is confirmed by the fact that none of the piece attributable to each workshop overlap with those of the others.

To try to illustrate the particularities of this first tashi gomang in Densatil, we will retain the following few works, knowing that we will limit ourselves here to evoking the dominant styles and that the secondary styles will be the object tashi gomang by tashi gomang of future publications.

The Four Guardian Kings

Fig. 15

One of the first pieces that can be attributed to this first tashi gomang is a Dhritarashṭra figure photographed by Michael Henss in the Jokhang of Lhasa together with two others from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. As the latter two are recognizable in the photographs taken by P.F. Mele at Densatil in 1948, the probability that this one also comes from Densatil is therefore very high.(Fig.15)

Fig. 16

The representations of these lokapalas will be very interesting in the course of this demonstration, since we have identified eight different types that can be attributed to each of the eight tashi gomang stupas and guide us in the chronology. His costume consists of a kind of armour combining textile, mail shirt, straps and ornamental plates following an iconography imported from China. Such representations can be seen in some paintings of the same period associated with Indo-Nepalese style deities such as we will meet mostly on the tashi gomang stupas (Fig.16). We note, however, that on this Dhritarashṭra, if the Chinese influence is present on the garment, the head and tiara can be judged as belonging to the same Indo-Nepalese style as the majority of the deities that will be associated with this monument.

In the best-known photographs of Densatil's tashi gomang stupas, the four figures of guardians appear arranged in front of the monuments, at the level of the protective deities and the great lotus. In the photograph that we can consider as representing this first tashi gomang for Dragpa Tsondru, the clear space in front of the three deities suggests that the lokapalas were not here arranged in this location. They were more likely directly rest on the great lotus. It is this layout that can be seen on the eighth tashi gomang, creating a new similarity between the two monuments, which were probably neighbors.

It is also possible to propose to attribute to this monument, level by level, many sculptures including the following few.

Tier six

The three deities visible on the P.F. Mele's photograph (Fig.12) are cast in a global Nepalese style. They are leaning against and fixed to gilded copper plates decorated in repoussé with secondary deities surrounded by lotus scrolls. One of them is known. (Fig.17)

Fig. 17

The left side shows us four deities holding a kapala and brandishing a kartrika, which according to Jigten Gonpo's description of Tashi Gomang for Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa, indicate that the deity who was to stand in front was undoubtedly an aspect of the goddess Lhamo (Prānasādhanā Śrīdevī). On the other part of the plaque was to be fixed a representation of the goddess Prithivi (Pṛthivī). This tells us that this plaque must have been on the east side of the monument, just like the three deities in the 1948 photograph, but at the other end of this side.

This back plate, executed in the exact style visible in P.F. Mele's photograph, also highlights the mounting system with a central joint and a hole for the deity's fixing hook, which is also seen in the photograph. (Fig.18)

Sculptures potentially attributable to this level were probably executed by several different artists. Many of them show a clear stylistic unity, essentially marked in the treatment of the bodies, tiaras with central anchor-shaped elements, armbands, bracelets and anklets, and garb elements and scarves.

We can attribute a number of figures to this level, including at least five Nagarajas now in the Capital Museum in Beijing. Two of them are illustrated here (Fig. 19). Note that each of them has a different costume and ornaments, which will also be the case on all the following tashi gomang stupas. A study of the set would perhaps make it possible to identify each of them by these costumes and jewels. The number of hooded snake heads above the nagarajas' bun will vary from tashi gomang to tashi gomang. That of the photograph taken by P.F Mele seems to have nine of them, like the sculptures in the Capital Museum in Beijing.

Fig. 18 |

Fig. 19 |

Fig. 20 |

A representation of Rahu kept at the Capital Museum in Beijing, (Fig.20) which can only come from this first tashi gomang, and therefore from its southern side, presents a stylistic variant which is expressed in the treatment of the ornaments with a motif in the form of a blooming flower forming a jewel as the main mark in the diadem. This particularity, which was probably applied to other deities at this level, at least on the south side, is also found on the tiaras of certain deities that we will find on tier 5 and inspired certain artists who worked on the 15th century tashi gomang stupas. His armbands seem to be closer to the model worn by the representation of Mahakala in P.F. Mele's photograph.

Tier 5

Fig. 21At this level were panels supporting on each side of the tashi gomang stupas the group of the sixteen goddesses of sensual enjoyment bearing offerings. These offering goddesses are linked to the Chakrasamvara suite, as can be seen in the lower register of a famous thangka from the Pritzker collection. (Fig.21)

These panels supporting the offering goddesses are present on each of Densatil's eight tashi gomang stupas and are easily reunited into eight distinct groups that can be associated with each of these eight stupas. The plates attributable to this first tashi gomang once again illustrate the diversity of the artists who worked on its construction. What they have in common is the lotus pedestal composed of 23 to 25 petals, depending on damages and what can be seen in the photographs. This is the only series to have so many lotus petals in such large numbers, which confirms their common origin.

Their overall Nepalese style with tiaras showing a central anchor-shaped element makes it possible to link them to the artists who worked on tier 6. (Figs. 22 & 23) One of them presents a slightly different style with goddesses wearing tiaras in the form of blooming flowers of the same type as what we have observed on the south side of tier 6 on the representation of Rahu. (Fig. 24) One might be tempted to see in this an indication that a particular workshop may have worked at least on the southern side of this tashi gomang. Another plaque closer to the first two (Figs. 22 and 23) seems to synthesize the two styles by also presenting the diadem with jewels in the form of blooming flowers. (Fig. 25)

Fig. 22 |

Fig. 23 |

Fig. 24 |

Fig. 25 |

Fig. 26Only one sculpture that has come down to us could be considered to have been part of the twelve that were grouped three by three at this level on each side of the monument. Considering the very small number of one-faced and four-armed goddesses mentioned in the description of the tashi gomang for Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa, it is conceivable to consider as an aspect of Chunda this four-armed deity holding a vajra, a blossoming lotus, and a triple jewel. (Fig.26) Chunda was a very popular goddess in ancient India, which seems to have quickly become confused with aspects of Tara when it spread to Tibet. Although it is difficult to identify, probably because it is described according to ancient texts, its iconography is recurrent in most of the eight groups of sculptures, and thus constitutes a good chronological indicator of the evolutionary sequence of the tashi gomang stupas. It is also executed in a mixture of Nepalese and remains of Pala styles and rests on a lotus base supported by a stepped plinth. This characteristic type of base associating lotus and stepped plinth will be assigned without absolute logic to certain deities throughout the 168 years during which the tashi gomang stupas were built.

Tier 4

At this level are normally the representations of Buddhas. As the number of Buddhas that could come from Densatil's tashi gomang stupas is extremely small, perhaps because those who extracted them from the ruins have piously preserved them, it is delicate in the present state of the documentation to attribute precise images to them.

On the other hand, we can identify at this level some very interesting representations. The central Buddha figures were flanked by two of the eight Bodhisattvas of the bhadrakalpa and two wrathful deities on each side. Coming from the eastern side, we can mention Maitreya and Aparajita (Fig.27) which were cast on the left of the background plate in front of which an image of Shakyamuni was to be placed. From the south side, Vajrapani and Acala (Fig.28) had to be placed also on the right side of the central Buddha. These two groups are executed in a style that is certainly Nepalese, but also betrays a classical Pala influence.

Fig. 27 |

Fig. 28 |

Fig. 29 |

At each corner, to the left of the spectator, were four guardian deities, Vajrankusha, Vajrapasa, Vajragantha and Vajrasphota. A representation of the latter attributable to this first tashi gomang is known. (Fig.29) It was placed on the west face at the northwest corner of the tier. The most characteristic elements of this style appearing on this object are the treatment of the lotus pedestal, the scarf, the earrings and the tiara with circular elements that may also evoke blooming flowers.

This sculpture is the first one really attributable to a particular workshop which seems to have mainly worked on the upper half of the monument.

David Weldon recently published an article [30] isolating this style by analyzing 14 objects attributable to this workshop. He has clearly shown for all these objects that they must have been executed by a workshop of artists most probably of Nepalese origin but working in a style strongly influenced by the aesthetics of India Pala.

Proposing a dating of the 13th century for this set he refutes a possible provenance of Densatil by forgetting the existence of this first tashi gomang of 1267. To further isolate this group from those generally attributed to Densatil, he argues that in Densatil the tangs that fixed the sculptures to the monuments emerge from the backs of the deities whereas in this group they emerge from the backs of the lotus pedestals. However, the examination of the whole corpus of objects coming from Densatil reveals that the tangs can, depending on the case, be placed either on the backs of the deities or on the backs of the lotus pedestals. Some objects sometimes do not show tangs.

He suggests that many other shrines may have housed such monuments.

However, since all fourteen of the objects he studied, totally fit into the very specific iconographic scheme of the Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa memorial stupa as visualized by Jigten Gonpo in 1198 with 2,800 deities represented on its surface, it is unlikely that they could have adorned a monument anywhere else than in Drigung or Densatil. For the reasons already mentioned above, and in particular the destruction of Drigung in 1290, the most likely hypothesis seems to be that these sculptures may have come from the upper part of Dragpa Tsondru's Tashigomang in Densatil.

His remark on the strong Pala influence present on this group of objects is very interesting, as it could be an additional clue to add to other points to measure the contribution of the Khasa Malla rulers who made numerous and important offerings to Densatil and other Tibetan monasteries throughout the thirteenth century. This is probably related to the fact that many monasteries dependent on Drigung were established in western Tibet by Jigten Gonpo.

Tier 3

From this level, the majority of the sculptures seem to come from the workshop we have just mentioned above with the Vajrasphota. Careful examination of these works allows us to be certain that this workshop must have been composed of several artists who did not all showed the same talent.

Among these objects on this tier 3, we can mention an Amitabha from the east side (Fig.30), and a Vajrasattva from the south side (Fig.31). We will focus on a one-faced four arms female deity. His lotus pedestal lotus is spread out over two lions. (Fig.32) Two of his hands are in Dharmachakramudra and the other two are in meditative attitude. Two lotus flowers bloom above his shoulders, respectively supporting a conch and a book. Considering the very small number of one-faced and four-armed goddesses mentioned in the description of the tashi gomang for Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa, it is conceivable to consider this one as a rare aspect of Prajnaparamita. This could be confirmed by the presence of a book over his left shoulder.

Fig. 30 |

Fig. 31 |

Fig. 32 |

These deities, like many others from the tashi gomang stupas, rest on lotus pedestals, themselves arranged either on stepped bases on which are represented the animals constituting their vehicles (vahana), or the stem and the lotus scrolls supporting the blooming flower, sheltering in their foliage the same vehicle animals. Once again, this particular form evokes certain aspects of Khasa Malla art.

A Hayagriva, still in the style of this workshop, was to be found on the north face (Fig.33). With the exception of the armbands which here resemble those of the peaceful deities mentioned above, he wears the same type of scarf, earrings and tiara with circular elements that may also evoke blooming flowers than those of the Vajrasphota in Tier 4. Still in the same style, a standing Acala now preserved at the Potala was originally intended to be positioned on the west side (Fig.34).

On each left corner (from the viewer's point of view) of each side of this floor were representations of Acala. One of them (Fig. 35) is currently preserved in the Jokhang of Lhasa.

Fig. 33 |

Fig. 34 |

Fig. 35 |

Fig. 36 |

Founded in 1351 by Changchub Gyaltsen (Byang chub rgyal mtshan), close to the Neudongtse palace, Tsetang was in fact the second great spiritual place of the Lang/Phagmodrupa clan along with Densatil. More than a simple Phagmo Drupa monastery, it seems to have been a large open center for Buddhist studies where masters of all schools were widely welcomed.

If Namkha Tsenpa was originally from Tsetang and was able to follow studies that led him to an abbatial throne in Sangphu, it is likely that he came from a family of a certain rank, possibly associated with the Lang/Phagmo Drupa clan. The path of a sculpture possibly originating from Densatil to Sangphu could this way find a form of explanation.

In his brilliant contribution to David Weldon's article, Yannick Laurent explains that Namkha Tenpa occupied the abbatial seat of gLing stod, the superior college of Sangphu during the last quarter of the fifteenth century. [31] He says he hasn't been able to track down to which collegiate school Namkha Tenpa belonged. In his study on Sangphu [32] Karl-Heinz Everding refers to his various colleges mainly of the Kadamapa and Sakyapa traditions. He mentions two of these colleges, sGros rnying and sGros gsar, which are said to have been linked to the Kagyupa traditions. [33] Perhaps this is how Namkha Tsenpa from Tsetang was introduced to Sangphu which was predominantly linked to the Kadampa then Gelugpa school, with whom the Phagmo Drupa always maintained privileged relationship.

It is absolutely obvious that the Acala once kept in Sangphu was made in the same workshop as the one now preserved in the Jokhang. It is also clear that this workshop is the same one from which the majority of the objects we attribute here to the upper part of the tashi gomang for Dragpa Tsondru come from.

We will never know exactly where this sculpture was cast in the thirteenth century, nor by which meanders in history it may have found its way to Sangphu two centuries later, but the existence of two identical Acala on a tashi gomang is not technically impossible, since one was originally placed at each corner of the third tier.

Careful examination of P.F Mele's photographs clearly shows that in 1948 some of the tashi gomang stupas' sculptures were no longer exactly arranged according to the original plan of Jigten Gonpo's vision, that some were missing or replaced by deities unrelated to those that should or could have adorned a tashi gomang of the Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa commemorative type. This implies that many of these sculptures may on certain occasions, perhaps for the maintenance of the monuments, have been removed to be replaced on subsequent tashi gomang stupas or possibly offered as relics to certain abbots.

Tier 2

On this level, we can mention a Vajrayogini today kept at the Capital Museum in Beijing. It is characteristic of this style with the typical scarf, and must have been located on the west side of the tashi gomang. (Fig. 37) It is almost identical in all respects to those we will find on the upper level with the only difference that it is resting on a classical lotus pedestal.

Fig. 37 |

Fig. 38 |

Fig. 39 |

The two are iconographically almost identical and should therefore represent Sadakshari and Chintamani who respectively occupied the south-eastern and south-western corners of the monument.

Tier 1

On this last level, the objects are arranged around the large Kadampa-type stupa.

Most of the figures clearly attributable to this level are in the style of workshop we are speaking about from tier 4.

The most significant group consists of Vajravarahi figures (Fig.40) that were originally arranged around this last level, thus strongly marking the association of the entire monument with Chakrasamvara. The descriptive texts of the "Reliquary Stupa of Many Auspicious Doors for Phagmo Drupa" respectively translated by Christian Luczanits and Olaf Czaja mention the presence of three of them on each side.

Fig. 40 |

Fig. 41 |

Still associated with this workshop, among the lineage of masters, one must mention a representation of Mahasiddha Kukkuripa and his dog from the Capital Museum Beijing, (Fig.42) as well as another figure kept at the Potala of Lhasa brandishing a kartrika above a kapala (Fig.43) This last figure was identified as Nairatmya by David Weldon,[34] but this seems impossible for many reasons. The first is that the character is resolutely masculine, which explains why Ulrich Von Schroeder identified it as an aspect of Padmasambhava. The second reason is that no representation of Nairatmya exists in the iconographic scheme of the Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa memorial tashi gomang stupa. It must therefore be a mahasiddha who remains to be identified more precisely, or as Ulrich Von Schroeder proposed, an aspect of Padmasambhava since a representation of this character is part of the list of lineage members to be present on this tier one.[35] However, Christian Luczanits considers difficult to imagine that a Padmasambhava figure could be encountered in 1267. If, however, Ulrich Von Schroeder's intuition was right, it could be one of the first representations of this master. [36] It should be noted that these representations are not resting on lotus pedestals.

Fig. 42 |

Fig. 43 |

Fig. 44 |

Fig. 45 |

The comparison of this work with a drawing now kept at the Rubin Museum in New York (Fig.45) is interesting at more than one point in reaching the top of this first tashi gomang. This textile drawing shows traces of regular folds, suggesting that it was originally part of the consecration charge of a sculpture or reliquary. He presents Chakrasamavara embracing Vajradakini between the footprints of Jigten Gonpo. As on the thangka depicting a lama mentioned above (Fig.14), the lower register shows us a row of lotus scrolls surrounding various protective deities as well as Nagarajas supporting the throne of the deity as on the tier 6 of a tashi gomang. These scrolls go up the sides of the composition to surround a line of masters and Mahasiddhas, again including Atisha, as on the first tier of a tashi gomang. Leaning against a background of flames, Chakrasamvara and Vajrayogini are executed in a graphic style totally echoing that of sculpture, as much in the ornaments as in the scarf ending in fish tails style, or in the circular floral element at the base of the buns behind their skulls crowns. This similarity must be seen as the expression of a strong artistic tradition, both pictorial and sculptural, attached to the monasteries of Drigung and Densatil during the thirteenth century.

Fig. 46

Pillars

On all the tashi gomang stupas, from levels two to five, the floors are connected by pillars, each decorated with two leaning four arms bodhisattvas forming caryatids resting on lotuses emerging from a kalasha (immortality liquor vase). The two leaning bodhisattvas are generally male and female.

Of the eight tashi gomang stupas, it should be noted that these pillars do not always appear to have been executed with great care. Examination of the sets clearly shows that some, probably the most visible ones, could have been executed with great care, while the majority, although each time following a pre-established prototype, gives the impression of having been entrusted to poorly gifted apprentices. The general treatment of those attributable to this first tashi gomang is rather sketchy and does not show great homogeneity from one to another. Their general common point seems to be the rather small number and shape of the petals of the lotus on which they rest, and the fact that the capitals only present in their center a simple horizontal line where on the following monuments a row of pearls will appear. (fig.46)

Background plates

On all the tashi gomang stupas, from floors 2 to 5, the main deities are leaning against plates decorated in relief with numerous smaller deities. It is these very many deities distributed over the eighty plates arranged on these four levels that make it possible to arrive at sets of more than 2,800 figures on each tashi gomang. It would seem that in the majority of cases, at least for the first seven tashi gomang stupas, these plates supporting the offering goddeses on the fifth tier and the Buddhas on the fourth one have been cast. For the two upper tiers (2 and 3) on which the deities appear surrounded by lotus scrolls illustrating the mandalas of those who were positioned in front of them, it seems that they were treated using the repoussé technique. By stylistic association with the plate from tier 6 mentioned above, and those visible in the photograph by P.F Mele, we can propose the attribution of two plates to this first tashi gomang. Both are today at the Museo d’Arte Orientale of Torino (Italy). The first is a fragment of the Vajradhatu mandala occupying the east face of the third tier. (Fig.47) The second is associated with Avalokiteshvara and must have been on the west face of this same third level. (Fig.48)

Fig. 47 |

Fig. 48 |

Abbot 5 / Stupa 5. Rinchen Dorje (Rin chen rd -rje) (1218-1280)

Rinchen Dorje acceded to the throne of Densatil in 1267 and is considered a reincarnation of Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa. This is undoubtedly related to the Lang/Phagmo Drupa clan's desire to increase its prestige by better linking Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa's direct spiritual lineage to Densatil and thus to their clan rather than to Drigung. At the same time, it should perhaps be seen as an attempt to fight against the ascendant prestige of the Karmapa who in 1216 established a new system of succession to the throne of their school by recognizing Karma Pakshi (Karma pak shi - 1204-1283) as the reincarnation of Dusum Khyenpa (Dus gsum mkhyen pa) who died in 1193.

Olaf Czaja believes that a tashi gomang of the Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa type in Drigung was erected for Rinchen Dorje in Densatil by one of his disciples named Spu-rtogs. He relies on two points for this. The first is a reading of the rgya bod yig tshang and the deb ther dmar po[37], but in both cases, and mainly in the deb ther dmar po, the ambiguous turnings may also suggest a misinterpretation evoking the construction by Rinchen Dorje of Densatil's first tashi gomang for Dragpa Tsondru, the famous Spu rtogs having then been able to participate in the work.

It should be noted that the Blue Annals, whose author was close to the court of Lang/Phagmo Drupa and therefore well informed of everything that may have affected Densatil, only evokes for him his status as the reincarnation of Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa and the fact that he was at the origin of the tashi gomang of 1267 [38]. Nowhere else in the same book does it mention that one of his successors built one for him. The deb ther dmar po gsar ma mentions that Changchub Gyaltsen (1302-1364) is said to have had redevelopment work carried out in the Densatil mchod khang where were the tashi gomang of 1267 and the sku 'bum (sgo mang) built by him in 1360 [39]. This description seems to indicate that in the time of Changchub Gyaltsen, there were only two tashi gomang stupas of the Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa commemorative type in the main temple of Densatil.

Fig. 49

Olaf Czaja's approach also seems to rest on the fact that no stupa is attributed to Rinchen Dorje in the gnas yig of Chos kyi rgya mtsho next to those of Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa, Jigten Gompo and Dragpa Jungne in the center of the east wall of the temple. [40].

Another obstacle to accepting that a Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa commemorative type tashi gomang was erected in Densatil for Rinchen Dorje is that it is possible to establish eight groups of works that may have belonged to the eight historical tashi gomang stupas, but their stylistic chronology does not allow us to envisage that one of them could have been made in 1280.

If no commemorative stupa for an abbot considered as the reincarnation of the founder of the lineage is mentioned among the five arranged in the middle of the east wall, and no tashi gomang of the Phagmo Drupa type could be erected for him, it is because his commemorative stupa must have had another form.

Fig. 50

In the northeast corner, not far from the five Kadampa stupas in the center of the east wall and probably next to the site that must have been occupied by the tashi gomang of 1267 for Dragpa Tsondru, we can still see the remains of a huge stone-structured stupa that could be attributed to Rinchen Dorje, (Fig. 49) first of all because it is located in one of the oldest parts of the temple, and is in a way a counterpart to Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa's hut, of which he was considered the reincarnation and which was located in the southeast corner. Assuming that this classical stupa structure could have been covered with a rich decoration of repoussé copper sheets in accordance with common usage, it is not impossible to think that the iconography may have allowed it to be included, in a more modest way than the 1267 stupa, in the tashi gomang stupas category.

It is hardly conceivable that a great tashi gomang like the one in 1267 could have been built for Rinchen Dorje without having been commissioned by Dragpa Yeshe (Grags pa ye shes) who acceded after him to the throne of the monastery or of Mkhanpo rin rgyal or Byang gzhon who succeeded each other in Neudongtse in 1281/1282. Indeed, only the latter could logically have decided to erect such an important and costly monument in the monastery. This stupa, although restored, is the only original element still in place today in the reconstructed temple (Fig. 50).

Fig. 51

Abbot 6 / Stupa 6. Dragpa Yeshe (Grags pa ye shes) (1240-1288)

Having studied in Sakya with Phagpa (‘Phags pa), Dragpa Yeshe ascended the throne of Densatil in 1280. At his death in 1288, a large commemorative stupa of the same shape and size as Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa's tashi wobar was placed next to the three previous ones. In 1948, it stood with four other stupas of the same type and size, textile wrapped, on a tiered altar in the middle of the east wall of the main hall. It can be partially seen on the famous photographs by P.F Mele. (Fig.51)

The fourteenth-century stupas

Abbot 7 / Stupa 7. Dragpa Rinchen (Grags pa rin chen) (1250-1310)

Dragpa Rinchen ascended the throne of Densatil in 1288. During his twenty-two years at the monastery, he received a title from the Mongols giving him temporal power over the region. It is also during this period that the Sakyapa and the Mongols razed the monastery of Drigung and the tashi gomang stupas that it was supposed to shelter. From then on, the tashi gomang erected in 1267 at Densatil became the only surviving testimony of this type of achievement.

It is also known that under his ministry a king of Yatse (most probably a Khasa Malla sovereign) covered with gold the two stupas East and West of Densatil [41]. This description should most probably be interpreted as the making of two golden copper ceiling parasols or mandalas, placed above the tashi gomang of 1267 and the stupa of 1288 for Rinchen Dorje, which were to be placed side by side on the north wall, thus necessarily one to the east and the other to the west.

This event marks once again the strong links that seem to have been woven between the Khasa Malla kingdom and the monastery of Densatil, which are probably not alien to certain artistic developments in this monastery and would need to be the subject of a specific study.

This tradition of placing umbrellas including gilt copper mandalas above stupas intended to receive the relics of great figures seems to have been relatively common in Tibet, and in Densatil, since P.F. Mele's photographs show at least one above the tashi gomang commissioned by Changchub Gyaltsen in 1360. (Fig. 52)

Fig. 52 |

Fig. 53 |

Fig. 54 |

Upon his death in 1310, a large commemorative stupa of the same shape and size as Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa's tashi wobar was created. In 1948, it stood with four other stupas of the same type and size on a stepped altar in the center of the east wall of the main hall. It can be seen partially wrapped in cloth in the famous photograph by P.F. Mele. (Fig. 54)

Fig. 55

Abbot 8 / Stupa 8 / Tashi Gomang 2 - Dragpa Gyaltsen (Grags pa rgyal mtshan) (1293-1360)

Dragpa Gyaltsen occupied the throne of Densatil from 1310 to 1360. All sources unanimously confirm that his brother Changchub Gyaltsen (Byang-chub rgyal-mtshan) (1302-1364), who succeeded in unifying Tibet and regaining temporal power over the country from the Sakyapas, had a tashi gomang of the Dorje Gyalpo Phagmo Drupa commemorative type erected for him. The Lang / Phagmo Drupa clan now reigning over Tibet and being at the head of one of the most prestigious and richest monasteries, Changchub Gyaltsen had no choice but to revive this prestigious tradition to affirm the temporal and spiritual power of his family.

The stylistic analysis of the tashi gomang stupas visible in P.F. Mele's photographs and of the stylistic chronology of the groups of objects attributable to all of them makes it possible to propose that this second tashi gomang may be the one for which we have several photographs and is therefore the best documented. (Fig. 55)

We therefore have here more elements and therefore almost certainties about the objects that must have adorned it in the past.

To try to illustrate the particularities of this second tashi gomang, we will retain the following few works.

The Four Guardians Kings

The overall photograph gives a good view of the structure of the monument with the four lokapalas arranged in front. They were not seen at this location in the photograph of the 1267 tashi gomang, which could indicate that in this first example these Guardian Kings must have been resting above the lotus circle. Although they are still depicted dressed in some sort of armour, the whole is executed in a more Nepalese style than a century earlier with rich inlays of semi precious colored stones. Note the lotus pedestals whose lower petals are smaller than the upright ones.

Of the four kings in the photograph, a similar burnt bust of Virupaksha remains today in private collection. (Fig. 56 & 57)

Fig. 56 |

Fig. 57 |

Fig. 58 |

This tier of protector deities encircled by lotus scrolls is particularly visible in the photographs of P.F. Mele. (Fig. 58) The deities of the eastern and south faces appear on a background of lotus scrolls encircling secondary deities in relief.

It would seem that here as on the tashi gomang of 1267 for Dragpa Tsondru the deities were cast, and then fixed on the bakground plates. Even if none of these plates have come down to us, careful examination of P.F. Mele's photographs allows us to be almost certain that they are no longer as we saw on the 1267 tashi gomang attribution proposal, executed in repoussé copper sheets joined by their centre.

The fractures visible on all the edges of the cast plates that we will encounter on the following tashi gomang stupas might make us wonder if the complete circle on which the twenty-four deities were leaning could not have been cast in one time. Beyond the unlikely technical tour de force that this would imply, even if we can't doubt the talent of the Newar masters, it hardly seems conceivable. Chinese scholars have brought to light that the workshops for making cast objects intended for the Densatil monastery would have been located in the plain, on the opposite bank of the Yarlung Tsangpo. [42] It is difficult to imagine that such a heavy metal circle, three and a half to four metres in diameter, could have been loaded onto a ferry to cross the Yarlung Tsangpo and then transported up the mountain in one piece.

They seem in fact here to have been made by grouping two or three together in a single cast. A detailed photograph of the Vaishravana of this monument reveals a lotus stem, partially masked by the costume of a lokapala, attached to the plate by a tenon that seems to act as a cover for a joint.

According to Chunhue Huang, the rich local copper mines known in the 13th century are still in operation today.

The analysis of P.F. Mele's photographs provides us with a precise vision of at least five sculptures of this level 6 and allows us once again to see that beyond a globally common aesthetic, it is obvious that various artists worked on them at the same time. The Nagarajas and Vaishravana, like the lokapalas, wear tiaras with a large flower-shaped element in the middle and large circular earrings.

The Lhamo on the east face and Rahu on the south face wear tiaras without the central floral element, and simpler armbands. Rahu's earring is not a large disc either but is in the shape of a blooming flower with inlaid stones organized around another more in relief. This type of earring is found on a Druma (Fig.59) and an aspect of Mahakala (Fig. 60) buried in the ruins of Densatil, kept at the Capital Museum in Beijing, and logically coming from the north face of this tashi gomang. An aspect of Aparajita holding his vase surmounted by a triple jewel and wearing large circular earrings and a tiara with a circular flower in the centre could potentially come from the north face of this monument. (Fig. 61) A probable representation of the wealthy god Atavaka with a richly adorned body and probably holding two jewels whose inclusions have now disappeared should come from the southern side. (Fig. 62)

Fig. 59 |

Fig. 60 |

Fig. 61 |

Fig. 62 |

Fig. 63 |

Fig. 64 |

There is no doubt that this first opportunity for the new monarchy to make its mark and to strengthen its sacred image has favoured the blossoming of this ornamental wealth which for three quarters of a century followed the rise and fall of the Lang/Phagmo Drupa dynasty. From the erection of this monument in 1360, many deities saw the flowers usually engraved on their dhotis replaced by floral representations in relief inlaid with coloured stones. This unique treatment of dhotis is undoubtedly one of the few main markers that will help define the Densatil style.

Tier 5

We can attribute to this rank a series of offering goddesses detached from their background plates. Careful examination of P.F. Mele's photographs seems to reveal a gap between the back and the deities that must have been attached to it. This would seem to be the only tashi gomang to present this technical particularity. Mention of the use of silver on Densatil's tashi gomang stupas could perhaps shed some light here if we consider that the plates to which these goddesses were attached may have been made of silver. The variations in the treatment of these goddesses once again reveal the variety of artists who worked on the different sides of the monuments. (Fig. 65) Also to be noted here is a change in the iconography of these offering goddesses whose arms are more developed in movement to better expose what they present. Therefore, unlike those attributed to the tashi gomang of 1267, they no longer support any Khatvanga in the hollow of their arm.

Fig. 65 |

Fig. 66 |

Fig. 67 |

Fig. 68 |

Fig. 69 |

Fig. 70 |

Fig. 71 |

Tier 4

No background plaques with rows of buddhas attributable to level 4 of this second tashi gomang have come down to us. As for the Buddha statues that were to be placed in front, we stated earlier that they are paradoxically rare, whereas about twenty of them were to be placed on each of the monuments. It must be said that in so far as the Buddhas are poorly adorned, there are few stylistic elements apart perhaps from the lotus pedestals to link them to the production of the workshops that worked at Densatil and even less to a tashi gomang in particular.

A Buddha resting on an open lotus raised by a stepped plinth (Fig. 72) could be attributed to this second tashi gomang. A group representing Maitreya and Aparajita (Fig. 73) is most likely the one that would have been to the right of the central Buddha on the east side, but P.F. Mele's photograph is unfortunately not sharp enough to clearly identify it.

Fig. 72 |

Fig. 73 |

Fig. 74 |

Tier 3

The Amoghasiddhi formerly in the B. Aschmann collection now kept at the Rietberg Museum in Zurich should find its place on the east side of this tier (Fig. 75). On the south side, there must have been a Vajrasattva now preserved in Drigung (Fig. 76), and the Manjushri from the former Zimmermann collection (Fig. 77). According to the texts it should be the so-called “Lion of Debaters” aspect which usually presents him sitting on a lion. Lions are, however, represented in the scrolls under his lotus pedestal. We meet for the first time on the dhoti of this sculpture the realization of the typical floral decoration in inlays of coloured gems which will develop even more in the two following tashi gomang stupas.

Fig. 75 |

Fig. 76 |

Fig. 77 |