What Constitutes "the Hand of the Master"?

Paintings Attributed by Inscription to Si tu Paṇ chen

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions)

Fig. 1The brilliant scholar and artist Si tu Paṇ chen Chos kyi ‘byung gnas (1700-1774) (Fig. 1) was an adroit leader of the Karma Bka' brgyud order, and a true polymath influential in multiple domains of cultural and institutional life in 18th-century Tibet. In the field of the arts he is credited with the revival of the court style of the Karmapas - the Sgar bris, or “Encampment Style”- which became emblematic of his greater resuscitation of the Karma Bka’ brgyud tradition. We know a great deal about Si tu Paṇ chen’s involvement in the arts as his artistic activities are well documented in his own writings, as well as those of his followers. This provides a view of a Tibetan artistic tradition from the inside, giving insights into an artist and patron‘s intentions. There is a great deal of information in particular in these textual sources about the famous painting sets designed and commissioned by Si tu, which was the focus of the Rubin Museum of Art exhibition Patron & Painter: Situ Paṇ chen and the Revival of the Encampment Style in 2009, and Lama Patron and Artist: The Great Situ Paṇ chen at the Smithsonian Freer Sackler Gallery, DC, in 2010. But what of paintings that do not fall into these categories? Single works attributed by inscription that cannot be tracked in Si tu’s writings or the histories of his monastery? This is a difficult and murky subject Jackson does not discuss in his catalog, but it is an important aspect of the exhibitions, which I would like to highlight here. [2David Jackson. Patron & Painter: Situ Paṇ chen and the Revival of the Encampment Style. NY: Rubin Museum of Art, 2009.]

A group of paintings bearing inscriptions attributing them to the hand of Chos kyi snang ba, one of the personal names used by Si tu Paṇ chen, were brought together for the first time in this exhibition. The gathering of these inscribed paintings provide us with a unique opportunity to consider for the first time the issue of paintings by Si tu’s own hand. While identifying works “by the hand of the master” is very basic to the field of art history, the area of Tibetan art is only beginning to be able to approach these fundamental concerns. Such an inquiry is not without challenges; for instance, more than one person in this tradition had the name Chos kyi snang ba, inscriptions themselves can be added later, paintings can be reattributed, and so on. This initial study will involve a close comparison of formal aspects of the paintings themselves, as well as the content and the calligraphy of the inscriptions, to each other and outside textual sources, as part of my analysis of five works.

Textual Sources

The two main primary sources on Si tu’s artistic activity are Si tu’s Autobiography and edited diaries: Ta’i si tur ’bod pa karma bstan pa’i nyin byed rang tshul drangs por brjod pa dri bral shel gyi me long; and Si tu’s biography contained in Si tu and ’Be lo’s Bsgrub rgyud karma kam tshang brgyud pa rin po che’i rnam par thar pa rab ’byams nor bu zla ba chu shel gyi phreng ba (Biographies of the Successive Masters of the Karma Bka’ brgyud School).[3Si tu Paṇ chen Chos kyi ’byung gnas and ’Be lo Tshe dbang kun khyab. Sgrub brgyud karma kaṃ tshang brgyud par rin po che’i rnam par thar pa rab ’byams nor bu zla ba chu shel gyi phreng ba (Biographies of the Successive Masters of the Karma Bka’ brgyud School). 2 vols. New Delhi: D. Gyaltsan and Kesang Legshay, 1972; and Si tu Paṇ chen Chos kyi ’byung gnas. Ta’i si tur ’bod pa karma bstan pa’i nyin byed rang tshul drangs por brjod pa dri bral shel gyi me long (The Autobiography and Diaries of Si tu Paṇ chen). New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture, 1968, hereafter referred to as Diaries. On these sources see Gene Smith’s “Introduction to The Autobiography and Dairies of Si-tu Paṇ -chen” (1968), republished as “The Diaries of Si tu Paṇ chen” in Among Tibetan Texts (2001), pp. 87-96.] Si tu’s close disciple and secretary ’Be lo Tshe dbang kun khyab (b. 1718) wrote Si tu’s biography, which he completed a year after Si tu’s death in 1775, and also edited Si tu’s diaries.[4See the colophon of Si tu and ’Be lo, p. 699.]

Si tu the Artist

Si tu Paṇ chen took an interest in art from an early age, and began to paint even before receiving formal training. At the age of fifteen, Si tu first learned iconometric proportions from a professional artist from Kong po during his first visit to central Tibet in 1714.[5David Jackson Patron & Painter: Situ Paṇ chen and the Revival of the Encampment Style. NY: Rubin Museum of Art, 2009. , p. 5 and p. 257, note 15. lha ris sngon nas rtsal bris lta bu’i phyogs mgo dod tsam yong thog kong po sprul sku las kyang thig rtsa ’ga’ zhig bslab/ Si tu Paṇ chen, Diaries, p. 45, line 6.] Soon thereafter at the Zhwa dmar’s monastic seat of Yang pa can, Si tu was shown old Indian cast-metal figures by a temple steward, who introduced him to the traditional stylistic classifications of Buddhist bronze sculpture. The steward pointed out different types of metal and characteristic shapes as he referenced one of the classic manuals on the evaluation of objects by the fifteenth-century authority Bya pa Bkra shis dar rgyas.[6David Jackson Patron & Painter: Situ Paṇ chen and the Revival of the Encampment Style. NY: Rubin Museum of Art, 2009. , p. 5 and p. 257, note 17.] Si tu was thus initiated at a very young age into a Tibetan tradition of connoisseurship. Si tu could paint in at least two different styles, Sman bris and Sgar bris, and was a keen observer of early masterpieces and different styles of painting. For instance in 1714 some of the first painting Si tu recorded studying were wall paintings of the “hundred adepts” by Sman bla don grub (founder of the Sman bris style in the 15th century).[7David Jackson Patron & Painter: Situ Paṇ chen and the Revival of the Encampment Style. NY: Rubin Museum of Art, 2009. , p. 5, and p. 257, note 20. This was also at Yangs pa can Monastery.]

Sets: Si tu’s Greatest (and Best Documented) Legacy

Fig. 2In 1726 Si tu painted one of his most celebrated and often copied sets of paintings: the “Eight Mahāsiddhas” (grub chen brgyad) (Fig. 2). This is the first set that Si tu recorded painting, which marks the beginning of his public life as an artistic and religious leader. They were offered to the Sde dge king Bstan pa tshe ring as he requested permission to build his monastic seat. In his autobiography Si tu recorded that he painted this set “in a manner like the Sgar bris” (sgar bris ltar) and did the sketch and coloring himself.[8grub chen brgyad kyi zhal thang sgar bris ltar gyi skya ris tshon mdangs dang bcas bris nas... Si tu Paṇ chen, Diaries, p. 140, line 7. Si tu’s depictions were variously arranged and combined in 9, 5, 3 painting sets and single paintings by later copyists. Jackson (2009), p. 258, note 39. For more on this set see: Jackson “Situ Paṇ chen’s Paintings of the Eight Great Siddhas: A Fateful Gift to Derge and the World” (2006).] This is a fine copy from the original set painted by Si tu, but to my knowledge they are only known to us in copies.

Fig. 3There is another (less famous) set, which Si tu records painting himself, the “Six Ornaments and Two Excellent Ones [of Indian Scholasticism]” (rgyan drug mchog gnyis) (Fig. 3). Si tu records in his diaries that while traveling along the road in northern Yunnan during the New Year of 1730: “Due to Dran thang sangs rgas’s urging, I painted several paintings [for him], and for bla ma Karma, I painted the Six Ornaments [of India] complete with coloring.”[9dran thang sangs rgyas kyis zhal thang ’ga’ re dang/ bla ma karmar rgyan drug gi sku thang rnams tshon mdangs bcas bris/ Si tu Paṇ chen, Diaries, p. 148, line 7. In his biography it records “Due to bla ma Karma’s urging, Si tu gave him the “Aspirational Commentary on Mahāmudrā” (phyag chen smon 'grel by the Third Karma pa Rang byung rdo rje) and paintings of the Six Ornaments [of India], and several paintings (zhal thang 'ga' re) to Dran thang sangs rgas [all] painted by his own hand.” klu chu mdor bzhugs/ rgyal lam yig zhu bar btang / sku’i gcung bla ma karmas bskul nas phyag chen smon ’grel dang / rgyan drug gi sku thang / dran thang sangs rgas la zhal thang ’ga’ re phyag ris gnang / Si tu and ’Be lo, p. 507, lines 6-7.] Si tu describes these paintings as “my new creation based on Chinese scroll paintings.”[10’di rnams kyang bdag gi rgya thang la cha bzhag pa’i gsar spros yin/ Si tu Paṇ chen, Diaries, p. 149, line 1. One can see that this composition is especially telling of Si tu’s familiarity with the internal visual language of Chinese painting. Here he pairs the greatest scholastic authorities of Indian Buddhism with bamboo, the Chinese symbol of the scholar, which bends with the changing political winds but does not break. This is not a random decorative choice but suggests that Si tu grasps the underlying meaning of the Chinese conventions he employs.

For this complete set of compositions see: Namgyal Institute of Tibetology 1962. rGyan drug mchog gnyis [The Six Ornaments and Two Supreme Masters]. Gangtok: Namgyal Institute of Tibetology. Second reprint, 1972; Jackson (2009), p. 121-2.] Several copies from the “Six Ornaments” set, including this painting of Nāgārjuna and āryadeva, are found in the Rubin Museum of Art collection. Again this set is only known to us in such copies, the fate of the originals given to his younger brother bla ma Karma is unknown. What is important to note in these passages is that they specify that Si tu painted these two sets himself “sketch together with color” (skya ris tshon mdangs dang bcas bris) and “complete with coloring” (tshon mdangs bcas).

Fig. 4Another more famous painting set perhaps most closely associated with Si tu Paṇ chen is Kṣemendra’s one hundred and eight morality tales, The Wish-fulfilling Tree (Dpag bsam ’khri shing; Bodhisattvāvadānakalpatā) (Fig. 4), in twenty-three paintings.[11For other copies of this final inscribed painting see: www.himalayanart.org/image.cfm/15135.html And of the set as a whole: www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=46 and an ordered numbering: www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=1097] Si tu Paṇ chen designed this set in 1733, soon after hearing the disastrous news of the sudden loss of his teachers, the Twelfth Karma pa, Byang chub rdo rje (1703-1732), and the Eighth Zhwa dmar, Dpal chen chos kyi don grub (1695-1732). Si tu sketched the compositions himself and set up a workshop for their execution. He personally directed the entire process of the painting, from the initial coloring to the finishing details. In order to realize his vision, Si tu trained a number of master painters of Kar shod to do most of the work.[12Si tu Paṇ chen, Diaries, p. 176; Si tu and ’Be lo, vol. 2, p. 519, line 3; Jackson (2009), pp. 11-12, and p. 258, note 49. Also see: Thub bstan phun tshogs (1985), p. 86.] In 1736 Si tu composed a long twenty-nine verse inscription, which would have appeared in this painting in the large blank scroll held up by goddesses, in which he outlines his intentions:

In the feeling/mood expressed, colors and drawing, [I] have followed Chinese masters, and for such elements as the land, dress, and palace [architecture], [I] depict them in accordance with what [I] had actually seen in India. These paintings also possess all of those discriminating [aspects] of the followers of the Sman thang, both New and Old, and the Mkhyen [bris] traditions, Bye'u sgang pa and the Sgar bris painters, but are distinctive in a thousand particulars of style/appearance (nyams 'gyur).[13tshon dang ri mo'i nyams rnam 'gyur/ rgya nag mkhas pa'i rjes 'brang nas/ yul dang cha lugs khang bzang sogs/ 'phags yul mngon sum mthong bzhin byas/ sman thang gsar rnying mkhyen lugs pa/ bye'u sgang pa sgar bris pa'i rnam dpyod de kun 'di ldan yang/ nyams 'gyur 'bum gyi khyad par byas/ This inscription is not recorded in Si tu’s collected works, it is only found on the last thangka in the set of twenty-three avadāna paintings. This inscription is recorded in the Dpal spungs scholar Thang lha tshe dbang’s Bod kyi ri mo byung tshul cung zad gleng ba (“A Brief Explanation of the History of Tibetan Painting”) published in Dkon mchog bstan ’dzin (2006), p. 218, which I follow here. Also see Thub bstan phun tshogs (1985), p. 86. This inscription is also translated and discussed by Jackson (2009), p. 12. Tashi Tsering (forthcoming, note 93*) points out discrepancies in the different recordings of this colophon.]

Here, Si tu names all of the major Tibetan painting traditions (New and Old Sman thang, Mkhyen bris, Bye'u sgang pa, and Sgar bris) as represented in his work to suggest the all-encompassing nature of his artistic vision. Clearly these paintings were the result of Si tu’s creative genius, but what I want to emphasize here is that while he conceived these works, sketched the compositions, and closely oversaw the workshop of artists which he assembled and trained to realize his vision, he did not paint them himself.

Fig. 5But what of paintings that are not part of these well documented sets? Of particular interest to me while working on this exhibition was bringing together paintings that bear inscriptions attributing them to Chos kyi snang ba, one of Si tu’s personal names. Chos kyi snang ba is part of a longer initiation name “Karma Bstan pa’i nyin byed Gtsug lag Chos kyi snang ba” which Si tu Paṇ chen received in 1713.[14This name was given to Si tu when he took his renunciation vows (rab ’byung) in Central Tibet at Mtshur phu Monastery. Si tu Paṇ chen, Diaries, p. 33, line 4. This passage includes an unusually moving account of his ordination. Si tu took full ordination in 1722, also at Mtshur phu Monastery. Ibid, p. 95.] Si tu used this name for himself, as attested to in colophons of several texts, including Si tu’s famous grammar treatise, where he refers to himself as “Gtsug lag Chos kyi snang ba.”[15For instance see his colophon in: Karma Si tu’i sum rtags ‘grel chen. Xining: Qinghai renmin chubanshe, 1957, p. 226.] Others also refer to Si tu by this name, for instance the noted 19th century Dpal spungs scholar Kong sprul (1813-1899), in his Shes bya kun khyab (“Embracing All Knowables”) (1864) when praising Si tu’s paintings also refers to Si tu as “Gtsug lag Chos kyi snang ba.”[16Kong sprul Blo gros mtha’ yas. Shes bya kun khyab (Kongtrul’s Encyclopedia of Indo-Tibetan Culture), International Academy of Indian Culture, New Delhi, 1970, folio 207b.] Si tu can also be found labeled in paintings by this name as well (Fig. 5), for instance in a painting of Indian and Tibetan masters in the Ashmolean Museum Si tu appears as a minor figure low in the foreground, with an inscription identifying him simply as “Ta’i Si tu Chos kyi snang ba” (dropping the “gtsug lag”).[17For an image of the complete painting see: Jackson (2009), figure 2.5; and jameelcentre.ashmolean.org/object/EA1991.180 and www.himalayanart.org/image.cfm?icode=81546.] However Si tu himself was not known to have used the name “Chos kyi snang ba” without “gtsug lag”, as recently confirmed to me by both the steward of Dpal spungs Monastery and another prominent local historian.[18Phyag mdzod A rgan bla ma, personal communication, October 2010. Karma Rgyal mtshan, a historian of Dpal pungs, also had never seen this.] This casts some doubt on whether these paintings, which are simply inscribed “Chos kyi snang ba”, are indeed by Si tu Paṇ chen. To complicate things even further, Si tu also used other names, most commonly (Si tu pa) Bstan pa’i nyin byed (another part of this same initiation name), which can be found in the colophon of the twenty-third painting of his Avadāna set previously mentioned,[19The last line of the inscription on the last thangka of the set of twenty-three avadāna paintings reads: Ces pa sha kya’i dge sbyong Si tu pa bstan pa’i nyin byed kyis bris pa dza yan tu//. See Tashi Tsering (forthcoming), appendix 1 for the full text. Also see Thang lha tshe dbang (2006), p. 218; Thub bstan phun tshogs (1985), p. 86; Jackson, (1996) p.286 note 640, and (2009), p. 258, note 50.] as well as the same name he used in many of his writings, such as in the title of his autobiography anddiaries.[20The Autobiography and Diaries of Si tu Paṇ chen: Ta’i si tur ’bod pa karma bstan pa’i nyin byed rang tshul drangs por brjod pa dri bral shel gyi me long; his collected works in Ta’i si tu pa kun mkhyen chos kyi ’byung gnas bstan pa’i nyin byed kyi bka’ ’bum; the text which details the contents of his stūpa, Byams mgon bstan pa’i nyin byed kyi chos sku’i mchod rten mthong grol chen mo’i dkar chag Rdzogs ldan gyi skal bzang ’dren pa’i ’khor lo rin po che zhes bya ba bzhugs so, etc.]

Works Attributed by Inscription to “Chos kyi snang ba”

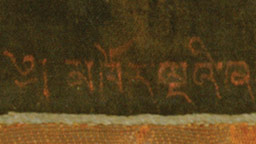

This painting in the Basel Museum of the goddess Vajravārāhī (Fig. 6a), identifiable by the distinctive sow head peeking out of the right side of her head, bears an inscription on the back naming “Chos kyi snang ba” as artist (Fig. 6b):

I bow with devotion to the blessed lady who embodies compassion combined with great bliss, the all-pervasive Perfectly Pure One, and pray that she pacify all my emotional defilements, thoughts and obscurations, and anoint me with the attainment of (the spiritual level of) Glorious Heruka! This painting was painted by the hand of Chos kyi snang ba. [21bde chen thugs rje’i bdag nyid bcom ldan ma/ kun khyab kun tu bzang mor gus ’dud te/ nyon mongs rtog sgrib thams cad nyer zhi nas/ he ru ka dpal thob pa’i dbang bskur stsol/ sku thang ’di chos kyi snang pas/ lag bris su bgyis pa’o/]

The use of the non-honorific lag for hand suggests that it was written by the artist Chos kyi snang ba himself, and not by someone else as an attribution.

Fig. 6a |

Fig. 6b |

Fig. 6c |

Fig. 6d |

(Fig. 6c) The condition of the object, with its badly abraded surface and deeply darkened ground, makes it difficult to evaluate the brushwork of the painter. Still, it is clear that the painter had a good grasp of proportions, as the figure is well modeled; however, its execution belies a slightly naive quality, such as seen in the pig head (Fig. 6d), that one might expect from the hand of someone who is knowledgeable in the fields of art and iconography, though, like Si tu, not a professional painter. We can also observe some unusual qualities of this painting. Especially distinctive is the flat use of gold in Vajravārāhī’s round full body nimbus, which shines like the sun. The rounded flames also mirror the shape of the gold nimbus, suggesting a sophisticated aesthetic.

Another characteristic feature of this group of paintings is found above the Tibetan inscription (Fig. 6b), where lines of ornamental Lancana Sanskrit are written. While this is not in itself unusual for any one painting, we will see this is a pattern on the backs of all four paintings, in keeping with what we know of Si tu, who was also a great scholar of Sanskrit. In fact, Si tu was quite concerned with consulting original Sanskrit sources for the proper depiction of deities and even names those sources he used in configuring some of his sets, such as his set of twenty-seven tantric deities, which he designed in 1750, citing the Kālacakra and Samvarodaya Tantras.[22Jackson (2009), p. 13; Si tu Paṇ chen, Ta’i si tur, pp. 304-5. These are deities regularly propitiated in the monastic rituals of dPal spungs (dus mchod and sgrub mchod). See Jackson (2009), p. 125, citing Karma rgyal mtshan (1997), pp. 273 and 296.] Thus this painting embodies many of the elements we might expect from Si tu.

The back of a small painting of Cakrasamvara (Fig. 7a) recently acquired by the Rubin Museum of Art features an inscription in Tibetan cursive script that also identifies Chos kyi snang ba as the artist of this work: (Fig. 7b)

May the guru, great glorious Heruka in blissful union with Vajravārāhī, protect me in all lifetimes, and may I practice Vajrayana [Buddhism]! This painting [of them] was painted in the midst of distraction by Chos kyi snang ba.[23bla ma dpal chen he ru ka /phag mo mnyam sbyor bde ba ches/ /tshe rabs rtag tu skyong ba dang / /rdo rje theg la spyod gyur cig /ces pa’i bris thang ’di chos kyi snang bas rnam g.yeng bar gseng la bris/]

This language “painted in the midst of distraction” (rnam g.yeng bar gseng la bris) is quite self-deprecating, even dismissive, and no one else would dare to write about the work of a high incarnate lama in this way, and thus this inscription and painting are almost certainly by the artist Chos kyi snang ba, presumably Si tu himself.

Fig. 7a |

Fig. 7b |

Fig. 7c |

Fig. 7d |

(Fig. 7c) Like the Basel Vajravārāhī, this work is characterized by a small simple elegantly proportioned figure lacking the finesse of a professional painter. There are several close points of comparison between these two paintings (Figs. 6c & 7c). In particular the use of flat gold in the scarf framing Cakrasamvara is an unusual feature reminiscent of the Basel painting. There is also a similar handling of the green scarf end (seen at bottom left), a similar treatment of skull crowns, and in the flaming body nimbus a similar use of red and gold to highlight the flickering flame as well as a use of indigo to throw them into relief. A sophisticated aesthetic is also suggested in details of the RMA Cakrasamvara such as the subdued palette of the tiger skin and garland of severed heads. One oddity is Vajravārāhī’s right hand is missing a flaying knife, though close examination reveals that part of a handle is still visible. Also a strange sheen on the green of the deity’s scarf, where the pigments do not match, suggests some minor over-painting. This illustrates one must be cautious in what one singles out to focus on in a painting as characteristic of the artist, style, or period.

Others Painters Named “Chos kyi snang ba”

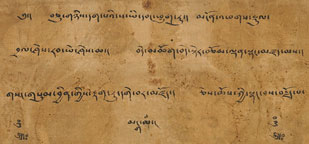

(Fig. 8a) As previously mentioned, Chos kyi snang ba is not a name unique to Si tu, and in fact he shared it with one of his most prominent students, the Eighth 'Brug chen Kun gzigs Chos kyi snang ba (1768-1822). We know the Eighth 'Brug chen was also interested in art, for instance he wrote an interesting text for a set of paintings of the mahāsiddhas.[24 The Eighth 'Brug chen’s collected works contain quite a few texts on the mahasiddhas = in vol. 14 (shrIH)? = such as the grub thob brgyad cu rtsa bzhi'i byin rlabs bya tshul gsal bar bkod pa mchog gi byin rlabs ye shes bcud (Ga - Nga, in thirty-two folio) which lists the eighty-four siddhas and describes them.] The Eighth 'Brug chen’s autobiography, written in the author’s fiftieth year (1817), is also a wealth of information.[25Mi pham chos kyi snang ba rang nyid kyi rtogs brjod drang po'i sa bon dam pa'i chos kyi skal ba pa rab gsal snyan pa'i rnga sgra (pp. 555-700 of vol. 2 (Kha - Tsam (in seventy-four folio) of his collected works). It is followed by a versified autobiography Rgyal khams pa bka' brgyud bstan pa'i rgyal mtshan 'gyur med yongs grub dam chos nyi ma'i spyad rabs nyung ngur bsdus pa nor bu'i 'phreng mdzes (pp. 701-720) and a supplement Rgyal dbang dam chos nyi ma'i rnam thar bsdus pa nor bu'i 'phreng mdzes kyi 'phros gsal ba skal bzang dad pa'i thod bcings (pp. 721-744) by the Fifth Bde chen chos 'khor yongs 'dzin Ye shes grub pa (1781-1845) that continues through 1822. The Eighth 'Brug chen’s autobiography and collected works is also the subject of one of Gene Smith’s legendary unpublished green notebooks: “Biographies. ’Brug-pa dkar brgyud-pa Volume VII” which he was kind enough to share with me.] This shared naming by a follower also involved in the arts calls into question the specific identification of Chos kyi snang ba in these inscriptions as either Si tu Paṇ chen or his student. For instance the previous Cakrasamvara also bears a resemblance to another, roughly contemporaneous painting of Cakrasamvara also in the RMA collection, bearing an inscription on the back written by the Eighth 'Brug chen (Fig. 8b):

“I bow with devotion to the great pair in sexual union, the wrathful meditational deity (Heruka) Glorious Cakrasamvara, together with his consort, teacher of the Great Secret (Vajrayana Buddhism), chief deity of all maṇḍalas! May all beings achieve guru Heruka!” [This was] painted as a support of the faith for the venerable yogini Bde chen dbang mo, by Bka' brgyud Bstan pa'i rgyal mtshan. May everything be auspicious![26gsang chen ston pa dkyil ’khor kun gyi gtso/ he ru ka dpal bde mchog btsun mor bcas/ mnyam sbyor zung ’jug chen por gus ’dud do/ skye kun bla ma he ru ka ’grub shog ces pa yang rje btsun rnal ’byor ma bde chen dbang mo’i dad rten du/ bka’ brgyud bstan pa’i rgyal mtshan gyis bris pa/]

Fig. 8a

Fig. 8b

Fig. 8c

Fig. 8d

Bka' brgyud Bstan pa'i rgyal mtshan is a name used by the Eighth ’Brug chen, as is evidenced in several colophons of his texts in his collected works (bka' 'bum). Also, the dedication is addressed to Bde chen dbang mo, a famous female yoga practitioner whom the Eighth 'Brug chen ordained circa 1804,[27The Ram pa lady Bka' brgyud dpal 'dzin 'chi med Bde chen dbang mo took her ordination from the Eighth 'Brug chen Kun gzigs chos kyi snang ba (also called Bka' brgyud bstan pa'i rgyal mtshan). The date of the ram pa lady's ordination is about 1804, which is mentioned on f. 51r of the Eighth 'Brug chen’s autobiography, and includes praise of her piety. Petech has mentioned the house of Ram pa in Aristocracy and government in Tibet, 1728-1959, p. 154. Several religious instructions addressed to the nun Bde chen dbang mo can be found in the Eighth 'Brug chen’s collected works, such as vol. Kha -Pi (7 folio) and another appended 6v line 4 - 7r line 3. Restoration work and the erection of new images by Eighth 'Brug chen at Ra lung were made possible through the patronage of the house of Ram pa. See: the Eighth 'Brug chen’s collected works, vol. Kha, Mo -Tshu (eighteen folio in length, including a descriptive catalog at the end).] about thirty years after Si tu’s death. We therefore know that this painting dates to slightly after Si tu’s time, but still within the lifetimes of his immediate followers. The end of the inscription is a bit ambiguous, and it is unclear if the verb bris[28bris can mean either “to write” or “to draw/paint.”] here means the ’Brug chen painted the entire painting or just wrote the benedictory inscription; however, when one requests a lama for a support (rten), one is typically expecting an image. Also, if this were simply a reference to the inscription, frankly speaking one would also expect that a prestigious lama like the ’Brug chen would have more talented professional painters at his disposal.

In evaluating paintings it is always best to compare like subject matter, as different genres have their own visual conventions. These two Cakrasamvara paintings (Figs. 7a & 8a) give the strongest basis for direct comparison through their shared subject, as the choice of color and basic forms of the deity are iconographically determined. In general terms, the approaches of the artists in these two paintings is similar in many respects: both pieces share an overall palette and minimalist approach that includes spare washes of soft blue and green which fade into blank canvas, acting to merely suggest a sky and landscape. Further, subtlety is visible in the handling of gold highlights in the flames, coupled with the use of indigo back-shading to throw the flames into relief. The overall execution of the deities’ jewelry and other ornaments are almost identical. However, the figures have more balanced proportions in the first work. A comparison of the right proper feet of the deities (Figs. 7d & 8c) will quickly reveal that the first painter (Fig. 7d) has excellent sense of proportion, while the toes of the latter (Fig. 8c) are clumsy and much too long. The shading is also more delicate in the first painting (Fig. 7c), while one can see the face of the second painting (Fig. 8d) divided into awkward artificial plains by a heavier application of pigment. All of this suggests different hands of non-professional painters of varying skill (I would argue the first by the master -presumably Si tu (left) - the latter by his student -’Brug chen (right), working in the same circle of artists. Also notice that the student ’Brug chen does not refer to himself in the inscription by the name Chos kyi snang ba, probably to avoid the possibility of just such confusion with Si tu. However, as a cautionary note, Tashi Tsering mentions the existence of three paintings preserved in Ladakh signed “Chos kyi snang ba” which he identifies as being by the Eighth ’Brug chen.[29Tashi Tsering (forthcoming), footnote 46.*]

The calligraphy on the reverse of these two paintings (Figs. 7b & 8b) is also interesting to compare, as they are both in an expressive cursive style, but careful analysis reveals that they are almost certainly by different writers. For instance, the letters are much smaller proportionately to the large calligraphic flourishes in the inscription by the Eighth ’Brug chen (Fig. 8b), which is actually in a more elegant hand. The calligraphy on the Chos kyi snang ba painting (Fig. 7b) is written in a characteristic running cursive (’khyug yig) style of eastern Tibet, but incorporates some flourishes of central Tibet, while the Eighth ’Brug chen’s is in more of a tshugs ma ’khyug style. The handwriting of Chos kyi snang ba is fairly distinctive, such as seen in the detail of the word “Chos” highlighted here, and looks very similar to the handwriting in manuscripts copied by Si tu and kept at Dpal spungs Monastery.[30In a photo that Tashi Tsering showed in his lecture at Latse Library, New York, on Feb 12, 2009 entitled “Situ Paṇ chen and the Palpung Literary Tradition: A Communication.” I have since tried to obtain copies of manuscripts written in Si tu’s hand for comparison, but without success. One sample of handwriting from the text dPal sdom pa ’byung ba’i rgyud kyi rgyal po chen po’i dka’ ’grel Pad ma can is said to have been copied by Situ Paṇ chen. The original dpe che is in the collection of Dpal spungs Monastery, scanned from a photocopy kindly provided by Tashi Tsering. This is the srisamvarodayamahatantrarajapadmini-nama-panjika which can be found in volume 21 (wa) of the Sde dge bstan 'gyur, pp. 4-204 (ff. 1v-101v). Yet upon closer inspection one finds a colophon in this manuscript actually names a dge slong Rin chen Chos kyi rgyal po as the writer, not Si tu Paṇ chen.] This further supporting evidence eliminates the possibility that the first painting of Cakrasamvara (Fig. 7a) is by the Eighth ’Brug chen, though it might by Si tu.

On the back of this painting of the tantric goddess Vajrayogini (Fig. 9a), also in the Rubin Museum of Art, is written a eulogistic prayer. The language of the inscription (Fig. 9b) makes it clear that Chos kyi snang ba wrote it; however, the inscription stops short of attributing this painting to him.[31Here he does not use the more ambiguous word bris (which could either mean “write” or “paint/draw”) but rather brjod pa, meaning “say”, so there is no confusion that this is only a reference to the inscription or verse, and not the painting itself.] It reads:

May your actions be forever virtuous through your blessings of the three secrets, Victorious Illuminator Goddess who bestows the pleasure of the highest bliss, gnosis-embodying goddess of immaculate wisdom who is exalted as mistress of the pure twelfth level of highest buddhahood! So say [I], Chos kyi snang ba. May it be auspicious! [32bcu gnyis dag pa’i sa yi dbang phyug tu/ mngon ’phags rdul bral shes rab ye shes ma/ bde mchog bde ster bcom ldan snang mdzad mas/ gsang gsum byin gyis rtag tu dge bar mdzod/ ces chos kyi snang bas brjod pa/ mangalam/]

Fig. 9a |

Fig. 9b |

Fig. 9c |

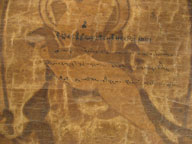

As a special blessing, after he composed this versified praise, he placed his own handprints onto the back of the painting using a saffron wash. It seems that based on textual evidence Si tu did this handprint practice only in the last years of his life, with only two recorded instances in 1772.[33Si tu’s diaries record only two instances of him placing his handprints on paintings: in 1772: “I added the imprint of my hands on the thangka painted by the [Thirteenth] Karma pa” Karma pa’i phyag ris thang ka’i rgyab tu lag rjes btab/ Si tu Paṇ chen, Diaries, p. 675, line 2 (folio 338r); and in the same year “I sent out such things as a thangka with my handprints.” bdag gis sug bris thang ka lag rjes can sogs bskur/ Si tu Paṇ chen, Diaries, p. 682, lines 1-2 (folio 341v). See Tashi Tsering (forthcoming), p. 18*, notes 61 and 62*. Note in the first instance he is placing his handprints on a thangka that he did not paint, much like the instance we see here.]

The calligraphy of this inscription (Fig. 9c) is quite close to the handwriting in the inscription on the aforementioned Basel Vajravārāhī (Fig. 6b), and it appears that these two texts were written by the same hand. The calligraphic style of both these inscriptions is ’bru rtsa script, which is popular in Khams. They are a little more formal in execution than that of the other two, more cursive, inscriptions discussed, and thus make a good comparison. While this style is a bit stiffer and less expressive, one can single out several characteristic letters, such as tu, where the top is often longer, and gyi, where the top of the gyi gu vowel is truncated, which suggest that these two texts were written by the same hand. Not only the painting style, but even the calligraphic style of the inscriptions themselves can be used to relate these objects to each other.

Works Attributed by Inscription Written by Others

Fig. 10aAnother level of evidence is paintings attributed by inscription written (often later) by someone else. For instance a painting of Black Cloak Mahākāla (Mgon po Ber nag chen) (Fig. 10a) on black silk is inscribed with the phrase “Without error [this] painting of Five Deity [Mahākāla] was painted by the hand of Chos [-kyi] ’byung [-gnas]” (Fig. 10b).[34 mkhor lnga’i zhar thang chos ’byung phyag bris ’khrul med lag/ [ ’ ]khor lnga’i zha[ l ] thang chos ’byung phyag bris ’khrul med lag[ s ]/] The many simple spelling errors, as well as the use of the honorific phyag for hand, are clear indications that this inscription could not be by Si tu, the strict grammarian. Still the silk brocades of this painting of Mahākāla (Fig. 10c) are in the distinctive mounting style of Dpal spungs Monastery,[35This observation was first made by Karma rgyal mtshan, a distinguished historian of dPal spungs Monastery who is quite familiar with its holdings. Personal communication, October 2010.] and help to tie this work to that artistic center and Si tu himself.

Fig. 10bOf all of the paintings considered so far, this deceptively simple work has a particularly expressive quality. What immediately draws the eye are the vibrant lines of the face which dominates the composition. Particularly effective is the subtle use of a green wash in the tunic to bring out the blackness of Mahākāla’s cloak on an already black ground, thus foregrounding the characteristic feature of the deity. This aspect is further emphasized by the simple ink washes framing the deity’s robe. This reflects a delicate aesthetic sensibility employed in the service of iconographic clarity.

Fig. 10cSeveral distinctive formal and material aspects of this painting also point to some of the artistic models that likely inspired some of Si tu’s works. Its unusual appearance, and specifically the sensitive handling of the animals, such as the realistic depiction of the elephant at bottom center, bears some resemblance to paintings attributed to the Tenth Karma pa Chos dbyings rdo rje (1604-1674). The resonance of this painting with works associated with Chos dbyings rdo rje is so strong that some have gone so far as to reattribute the painting to the Tenth Karma pa.[36The label in the “Portraits - Karmapa” exhibition at the Rubin Museum of Art (6/24/05- 10/16/06) did not mention this inscription identifying it as a work by Si tu Paṇ chen, and instead directly reattributed the painting to Chöying Dorje: “Choying Dorje (1604-1674) was a renowned painter fluent in both the Tibetan and Chinese painting styles of his time. This painting executed on black silk is attributed to Choying Dorje based on style, subject, and comparison with other Choying Dorje paintings. The composition is drawn freehand without the use of iconometric grid lines. Animal figures are always given special attention and lavished with greater detail and refinement than the human figures. Chöying Dorje is also known for painting on silk cloth.”] While a silk ground is unusual to Tibetan painting and something that the Tenth Karma pa was known to favor, the handling of the ink clouds here suggests a painter not familiar with how silk absorbs ink, or the techniques of creating layered ink washes -a characteristic technique at which the Tenth Karmapa was a master. Therefore the unambiguous inscription, combined with the simple unexpressive quality of the brushwork, suggests that Si tu painted this work following compositions by the Tenth Karma pa, or was at least inspired by that Karma pa’s distinctive style.[37For further discussion of the characteristic brushwork of the Tenth Karmapa and this painting attributed variously to Si tu and the Tenth Karmapa see chapters 3 and 9 of: The Black Hat Eccentric: Artistic Visions of the Tenth Karmapa (forthcoming, 2012).] Copying paintings by the great masters has long been a basic aspect of training and appreciation across many traditions and textual evidence confirms that Si tu Paṇ chen was particularly interested in the Tenth Karma pa’s artistic career. It is also recorded that Si tu was in possession of visual models by the Tenth Karma pa. For instance it is recorded in Si tu’s Diaries that in 1763 the ThirteenthKarma pa gave Si tu Paṇ chen thangkas paintedby the Tenth Karma pa depicting the twelvedeeds of the Buddha.[38Si tu Paṇ chen, Diaries, pp. 503-504.] Also, several paintings by the Tenth Karma pa, including images of Vajrapaṇī, Avalokiteśvara, the Sixteen Elders, and the Buddhas of the Three Times, were included in Si tu’s burial stūpa, which further suggests that not only was he in possession of visual models, but also that Si tu had a special relationship to them.[39See David Jackson, A History of Tibetan Painting: The Great Painters and their Traditions. (1996), p. 251, citing ’Be lo Tshe dbang kun khyab, Byams mgon, p. 713.]

Conclusion

Many problems remain in evaluating this group of inscribed paintings. All of these deities are very standard to the Karma Bka' brgyud tradition -so that mention in Si tu’s biographies and diaries is not necessarily confirmation of Si tu’s authorship of these paintings, as Si tu would be expected to paint these themes either way. For instance on his first visit to central Tibet in about 1713, Si tu visited Mtshur phu Monastery where his teacher the Twelfth Karma pa, Byang chub rdo rje (1703-1732) asked Si tu to paint a picture of Mahākāla in the form of Mgon po Ber nag can.[40David Jackson (2007), p. 4, quoting Si tu and ’Be lo, vol. 2, p. 458.3 (na 228b). Si tu left for Lhasa in 1712, at age 12-15.] But was it necessarily this painting? (Remember Si tu would have been about thirteen years old, before he had received formal training.) Ber nag can is after all the main protector of the Karma Bka' brgyud tradition, and Si tu would certainly have painted this theme repeatedly throughout his life. The dedicatory inscriptions on the paintings considered here are formulaic eulogies, with nothing specific to tie a particular painting to a specific textual reference. While one might hope to find the inscriptions themselves recorded in Si tu’s collected works, paintings such as these which are not part of famous commissions makes it unlikely.

And, most of all, how do we reconcile the fact that these paintings are of such a different character (and frankly quality) than other works which we most closely associate with Si tu, (Figs. 2 & 4) such as the Eight Mahāsiddhas and the Avadānas that we started with? This disparity was remarked upon with some surprise by critic Blake Gopnik in his March 21st 2010 review of the exhibition for the Washington Post when it traveled to the Sackler Gallery of Art, as this clearly flies in the face of most assumptions about works “by the hand of the master” being by definition superior to those of his workshop: “It's very hard to know what's from Situ's own hand, what was designed by him and then farmed out to artisans, what was commissioned by him, what is a close or distant riff on Situ's ideas or a much later copy of something from his time. (Strangely, the handful of newly discovered works that actually bear Situ's name are not the strongest in the show.)”[41Blake Gopnik “In 'Lama, Patron, Artist,' Lama's Legacy Immortalized in Images” Washington Post, March 21st 2010. Available on-line at: www.washingtonpost.com.]

Indeed Tashi Tsering, Director of the Amnye Machen Institute, in an excellent overview entitled “Si tu Paṇ chen and his painting style: a retrospective” forthcoming in the Si tu conference volume Situ Paṇ chen: Creation and Cultural Engagement in 18th-Century Tibet, has rejected these paintings as anything to do with Si tu.[42“A Vajravarahi thangka in the Essen collection and two Chakrasamvara thangkas at the Rubin Museum of Art, displayed on the occasion of the exhibition “Patron and Painter: Si tu Paṇ chen and the Revival of the Encampment Style” (February to August 2009) are attributed to Si tu Paṇ chen. Two of these paintings are signed by Chos kyi snang ba and the third by Bka’ brgyud bstan pa’i rgyal mtshan. From the viewpoint of a purely visual comparison of these thangkas with Si tu’s Skyes rabs dpag bsam ’khri shing and Grub chen brgyad-these two sets definitely being the product of Si tu Paṇ chen-the dull colours used in these paintings lack the vibrant and subtle nuances used by Si tu; and their rendition is remarkably coarse. I do not want to venture further in aesthetical considerations which I leave to the experts... ...The only thangka signed by Si tu Paṇ chen beyond doubt - the 23rd painting in the Jataka Tales set, which has been often mentioned in this study - bears the name Si tu bstan pa’i nyin byed. Hence the three above mentioned thangkas have nothing to do with Si tu Paṇ chen.” Tashi Tsering (forthcoming).] But what is the basis for comparison as the only paintings clearly by Si tu, and even “signed” by Si tu himself? The Avadānas, which Si tu tells us himself that he did not paint.[43For the paintings which Tashi Tsering considers the “original thangkas” from Si tu’s sets of the Eight Mahāsiddhas (Grub chen brgyad) and the Avadānas (Skyes rabs dpag bsam khri shing) see the first two images in his forthcoming article.] Rather it is a team of professional painters that Si tu oversees. One can see that issues of authorship -what actually constitutes a painting “by Si tu”- is a very complicated one.

When one comes across a passage in Kaḥ thog Si tu’s pilgrimage guide saying he saw paintings “by Si tu” are these by Si tu’s own hand or Si tu’s designs?[44For instance Kaḥ thog Si tu, p. 22, line 4; and p. 24, line 1.] Are the wondrous works praised by generations of Tibetan scholars like ’Jam mgon Kong sprul those painted by Si tu himself?[45For instance Kong sprul Blo gros mtha’ yas, folio 207b.] Or (I would argue) the works that he envisioned, designed, and realized through carefully orchestrated teams of professional painters? Indeed all such paintings (at least those that I have seen) are either designed by Si tu or even copies of Si tu compositions, no doubt in many cases by professional painters that Si tu employed in fulfilling his artistic visions, as is repeatedly attested to in Si tu’s own writings. I think it is important to keep our minds open to the possibility that these professional painters may have been more technically skilled than Si tu, and that these works we associate with Si tu are in many cases the product of the highly trained painters who were carefully overseen by Si tu and his successors. This is not a question unique to the study of Si tu or Tibetan art, as many famous artists in the west often had other painters complete their compositions. The inscribed works considered here may not in fact be by Si tu Paṇ chen, as we have established there were other Chos kyi snang bas painting, even within Si tu’s own circle -there is still not enough available yet to make these judgments.

A lot of important ground work has been done by David Jackson and Tashi Tsering in integrating textual records with the extant visual material, made available through the Rubin Museum of Art exhibition, catalog, and accompanying conference. As a result the later Sgar bris style and Si tu’s larger oeuvre is now the most clearly defined of any of the major Tibetan painting traditions in modern scholarship. Of course open access to the holdings of Si tu’s seat Dpal spungs Monastery will become critical for further study of Si tu’s works. Perhaps then original paintings done by Si tu himself, such as the “Eight Siddhas” and “Six Ornaments”, will become available. In the meantime the opportunity afforded to us now that these paintings have been brought together for the first time is an important first step in understanding Si tu the artist -a seminal figure in the history of Tibetan art. It also raises some basic art historical issues that are seldom addressed in the study of Tibetan Art, for which we have yet to develop a methodology.